Post-restructuring challenges for the Spanish banking sector

In the wake of the crisis, Spanish banks have become more solvent and returned to profitability. However, unique macroeconomic conditions, especially the current low interest rate environment, together with increased capital requirements, will require further efforts to boost efficiency and reinvent business strategies to secure positive profits going forward.

Abstract: The crisis had a severe negative impact on the Spanish banking sector. However, profitability has returned in 2013 and has since remained in positive territory, albeit constrained below pre-crisis levels in the context of the current low interest rate environment. As regards non-performing loans (NPLs), they have declined overall since their peak. Still, the concentration of bad loans related to construction and development, as well as the overall NPL rate in this sector, remains high. Finally, in line with more stringent new capital requirements, Spanish banks have improved their solvency indicators, with capital ratios for deposit-taking institutions that are above Basel III minimum requirements. On the downside, even though there have been significant reductions in employees and number of branches, Spanish banks have not been able to sufficiently increase efficiency indicators. Thus, despite notable progress post-crisis, today´s difficult climate requires further efficiency gains, together with the adoption of new business strategies reliant on increasing scale, internationalisation, and further expansion of on-line services in order to adapt to profitability challenges.

[1]

Introduction

The imbalances accumulated in the Spanish banking sector in the pre-crisis expansionary period ultimately forced a profound restructuring and reorganization of the sector. Imbalances were so severe in parts of the banking sector that the Spanish government had to request financial assistance from the European Union. The conditions established in the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) accompanying the assistance programme have helped bolster the sector’s viability. The restructuring and the end of the recession have been the cornerstones of the sector’s return to profitability and its ability to extend credit. Moreover, having provisioned resources equivalent to 27% of GDP to writing-off asset impairment losses since the start of the crisis, profitability of Spanish banks is now on the rise, along with the growth rate of new lending. At the same time, banks have made a significant effort to bring capitalisation levels in line with even the most demanding solvency requirements, as evidenced by the their successful performance on the ECB and EBA’s 2014 stress tests.

Nonetheless, in the wake of the financial crisis, the Spanish banking system still faces significant challenges for a number of reasons: i) the process of private sector deleveraging, although intense, is still incomplete, and is holding back the potential recovery in banking activity; ii) the current low interest rate environment is having a negative impact on net interest margins, limiting profitability; iii) the potential to offset the drop in interest income with earnings from financial transactions has lost momentum (low interest rates are making it difficult to obtain capital gains – i.e., lower interest rates on public debt have made the carry trade less attractive); iv) new capital requirements call for more and better quality capital, and capital is difficult to attract as the current yield offered to investors is low; and finally, v) the large volume of non-performing assets still held on banks´ balance sheets is slowing the recovery in profits and the reactivation of credit.

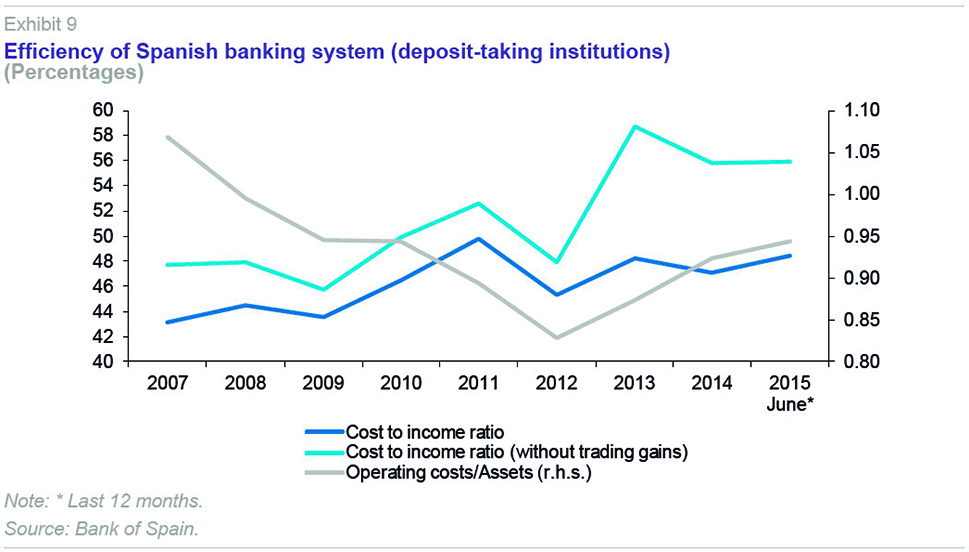

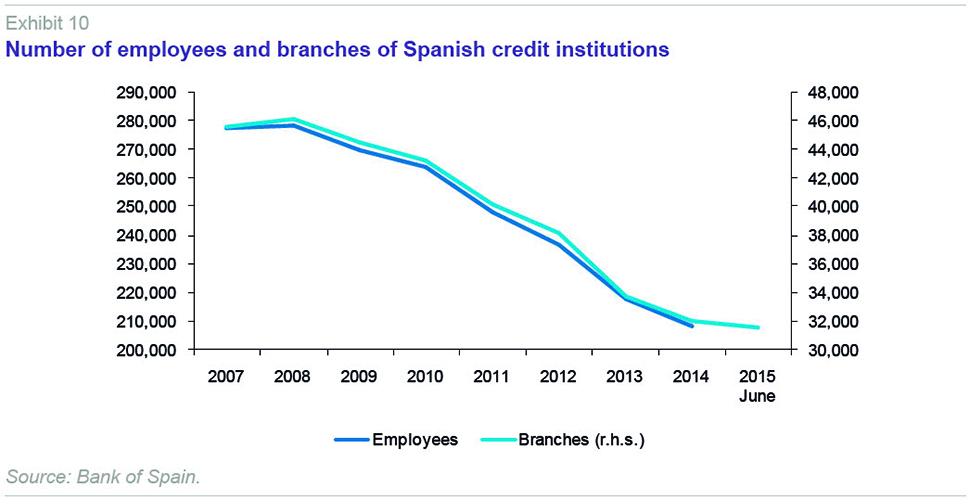

In this context, it is difficult to raise profitability above the cost of capital, making efficiency gains and cost rationalisation more necessary than ever. This is a challenging goal bearing in mind that, although the network of branches has been cut by 31% and jobs by 25%, it is proving difficult to reduce costs per unit of assets – they have even increased in 2014 and 2015. For this reason, efficiency gains have been hard to achieve and efficiency today is below pre-crisis levels.

On top of these difficulties, increased competition poses a no less important challenge. Competition is set to increase on two fronts: domestically, manifesting itself through a narrowing of the interest margin banks are charging on their loans as they try to win business; and, internationally, deriving from progress on the banking union. Implementing the two pillars of this union (the Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Resolution Mechanism), together with harmonisation of standards in the singe rule book, will bring about a more competitive marketplace.

Against this background, this article aims to analyse recent developments in the Spanish banking sector, over a period that captures both the impact of the crisis and the recovery, using the most recent data available, which refer to June 2015. Given the information available from the Bank of Spain, the analysis based on income statements (margins, profitability, efficiency, income structure, etc.) refers to deposit-taking institutions (business in Spain), while the rest of the analysis (activity, specialisation, capacity indicators, etc.) refers to credit institutions.

This article is subdivided into two sections: one analysing recent developments in the Spanish banking sector in terms of activity, specialisation, margins, profitability, liquidity, asset quality, solvency and efficiency; and another discussing the challenges facing the sector and the vulnerabilities it needs to overcome.

Recent developments in the Spanish banking sector

Activity and specialisation

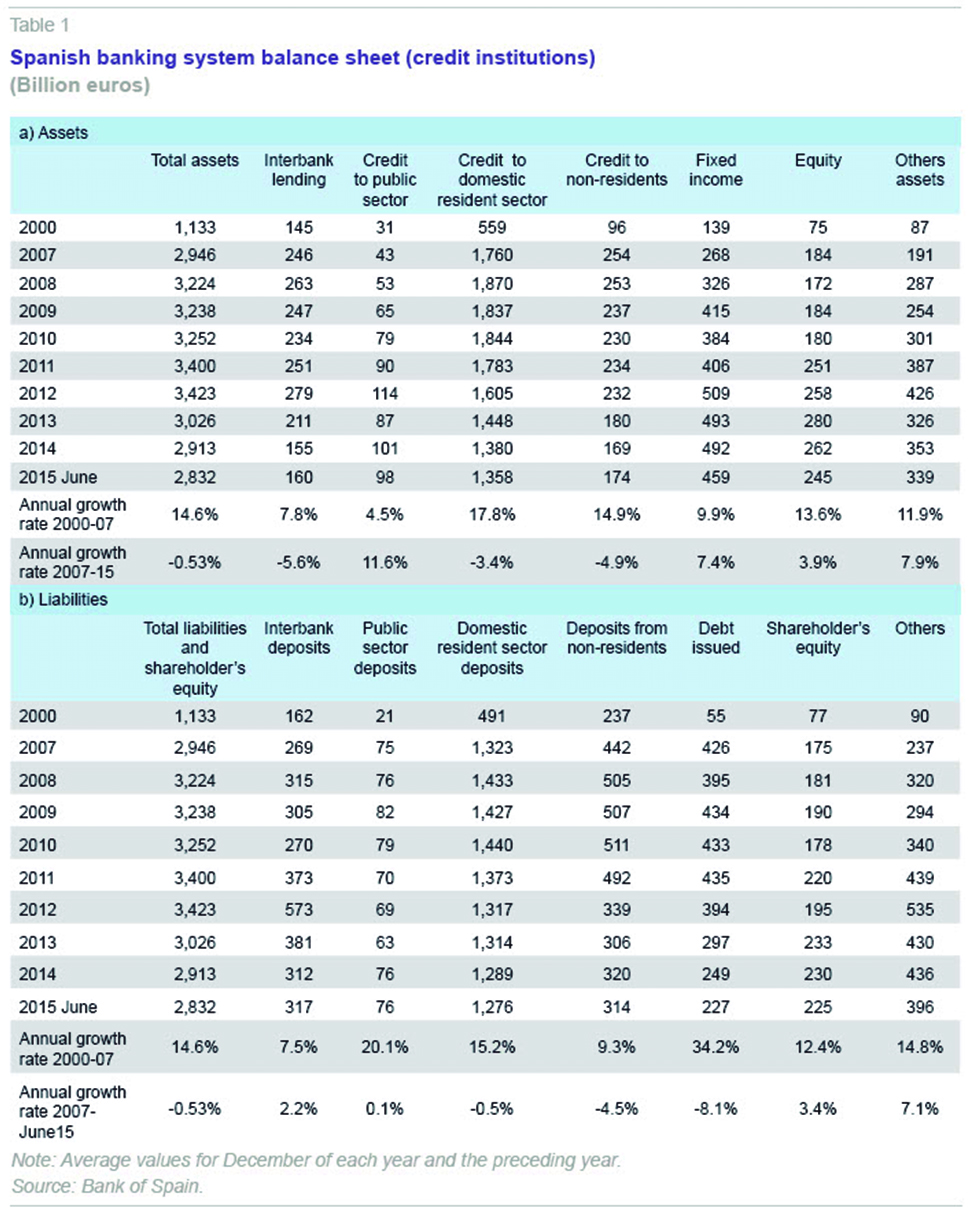

Following the rapid growth during pre-crisis expansion, the crisis made a clear impact on the size of the Spanish banking sector’s balance sheet. After growing at an average annual rate of 14.6% between 2000 and 2007, the rate turned negative during the crisis (Table 1). Nevertheless, assets continued to grow until 2012, subsequently dropping by 17% to June 2015. Given the weight of residential private sector lending in the balance sheet, both its intense growth in the expansionary phase (growing by a factor of 3.3 between 2000 and 2008) and the subsequent plunge (a contraction of 27% between 2008 and June 2015) explains how assets have evolved. Over time, the rate of decline has slowed, dropping to around 4% in mid-2015. The crisis barely affected growth in fixed-income investments, such that they account for a much larger share of the balance sheet today (16%) than they did in 2007 (9%). This increase is explained by investment in public debt, as it has more than tripled as a share of assets: from 2.9% in 2007 to 9.1% in 2015. Nevertheless, the current level is only slightly higher than that at the start of the 2000s. In the case of equities, their share of total assets is currently higher (8.7%) than it was before the crisis in 2007 (6.2%).

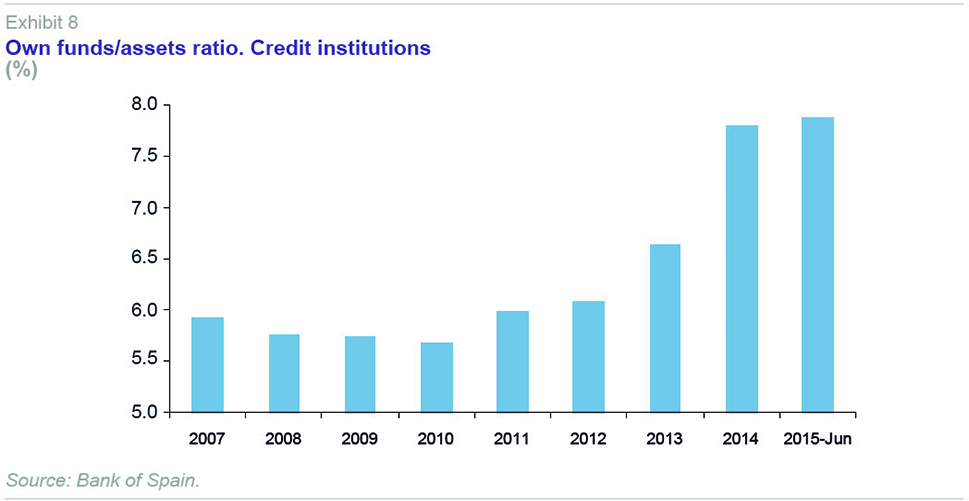

On the liabilities side, other resident sector (ORS) deposits have suffered the impact of the crisis. After growing at a rate of 15.2% up until 2007, since the crisis, their average growth rate has been -0.5%. This evolution is similar to that of the balance sheet as a whole, such that their share of assets remains 45%. As a consequence of banks taking full advantage of ECB financing, interbank financing peaked at 17% of assets in 2012, although it had slipped back to 11.2% in June 2015. Market issuance of debt grew strongly between 2000 and 2007, given the shortage of deposits to finance such rapid credit growth, such that it went from representing 4.8% of assets in 2000 to 15% in 2007. The difficulties accessing wholesale markets during the crisis had reduced this share to 8% in June 2015. Finally, the crisis caused own funds to shrink in relative terms to a minimum of 5.4% in 2010. However, the new regulatory requirements had obliged institutions to bring them up to 8% in the summer of 2015.

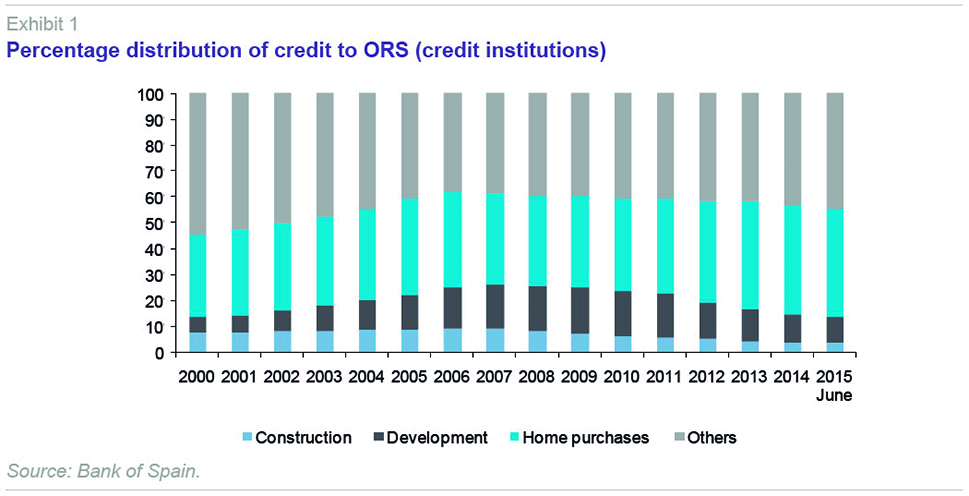

The composition of credit, the most significant variable concerning banks’ assets, changed substantially throughout the crisis relative to the years of expansion. As Exhibit 1 shows, lending to construction and property development activities peaked at 27% in 2007. Considering lending for housing purchases as well, the construction and property sector as a whole came to account for 61% of lending. This lending has subsequently declined, dropping to 13.6% and 55%, respectively, in June 2015. Given that, as we shall see, defaults have risen exponentially in the construction and property development sector, the biggest decline in credit has been in these two sectors, their total share of credit having halved.

Margins and profitability

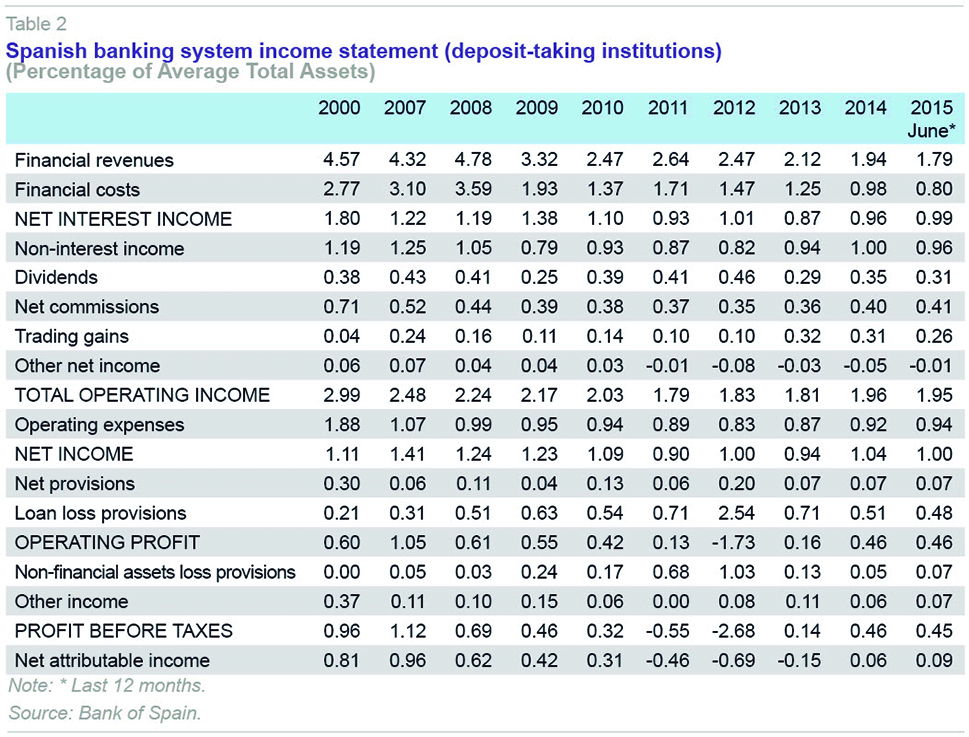

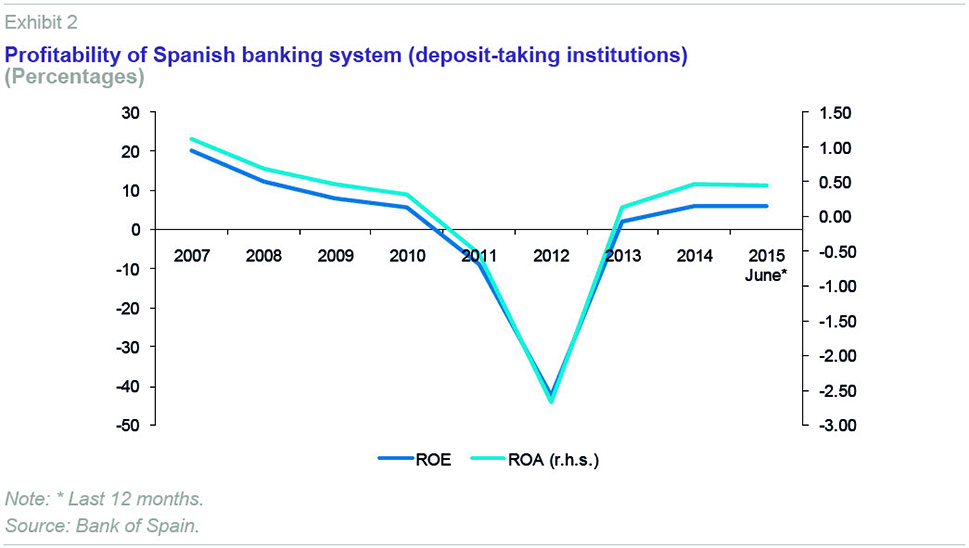

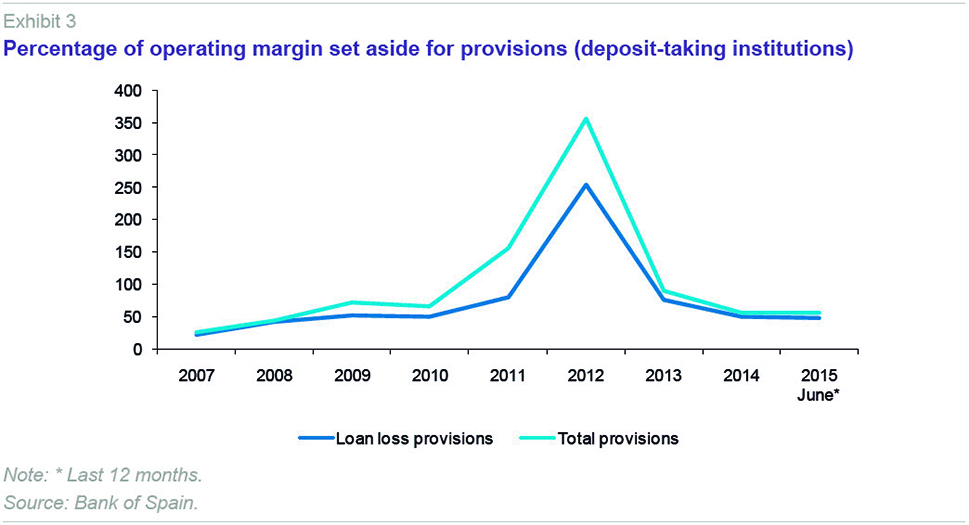

The crisis has adversely affected the quality and value of banks’ assets, necessitating massive write-offs. Between 2008 and June 2015, the Spanish banking system devoted 282 billion euros of net margin to provisions, to cover both financial (206 billion) and non-financial assets (76 billion). The Royal Decrees enacted in February and May 2012 required intense restructuring of banks’ property exposure, with provisions consequently coming to 356% of net margin that year, resulting in banks´ generating losses, with an ROA of -2.7% and ROE of -42.7%. Banks also recorded losses in 2011, with write-offs equivalent to 155% of net margin.

2013 was a turning point for banks’ profitability, as the Spanish economy emerged from recession in the second half of the year. After the restructuring of property exposure in 2013, the year ended with pre-tax profit of 4.2 billion euros – a profit of 0.14% in terms of assets, and 2.01% in terms of equity. The recovery in profits continued in 2014, with ROA of 0.46% and ROE of 6.01%. Up through the first half of 2015 (last 12 months) returns remained at 2014 levels, specifically 0.45% in terms of ROA and 5.86% in terms of ROE. These levels, however, are far from those reached prior the crisis in 2007: ROA of 1.13% and ROE of 20.2%.

The drop in money markets’ benchmark interest rates to record lows makes it difficult to make profits, as this squeezes net interest margins. Net interest income (as a percentage of assets) has halved since the early 2000s and is currently down almost 20% on its pre-crisis level in 2007. Nevertheless, the bigger drop in expenses than financial income in 2014 and in the first half of 2015 has allowed margins to recover slightly, and they are currently 0.99%.

Gross profit margins fell by 21% as a percentage of assets after 2007, but have been growing since 2011. Banks reacted to the drop in net interest income by increasing their income from fees and financial transactions. Fees rose between 2014 and 2015 to represent 0.41% of assets, and income from financial transactions tripled its share relative to its value in 2011 and 2012, with a value equivalent to 0.26% of assets in June 2015. Without these non-recurrent revenues, Spanish banks’ current profits would be halved.

Liquidity gap

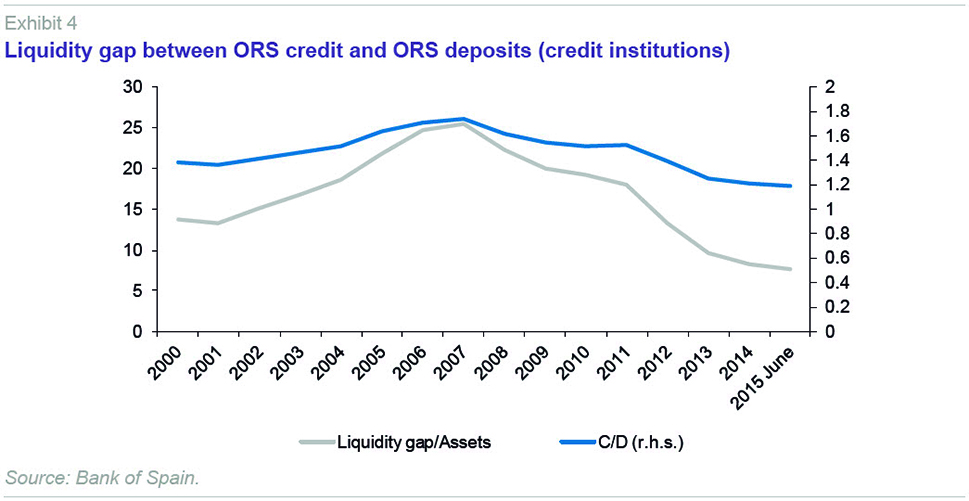

During the credit boom, the Spanish banking system accumulated a widening liquidity gap. However, the subsequent slump in credit has largely corrected it. Thus, the private sector loans-to-deposits ratio increased from 1.4 in 2000 to 1.7 in 2007, with the liquidity gap widening from a value equivalent to 13.8% of assets in 2000 to 25.4% in 2007 (Exhibit 4). In June 2015, it was below its 2000 level at 1.2, equivalent to 7.6% of assets. The gap, as a percentage of assets, is currently at a record low.

The reversal of the liquidity gap was not a consequence of a recovery in deposits, but rather of a collapse in credit. Thus, whereas between 2007 and June 2015, deposits increased by 13%, credit contracted by 23%. The biggest correction of the gap took place after 2011, and particularly in 2013, as in this year alone it shrank by 38% (165 billion euros).

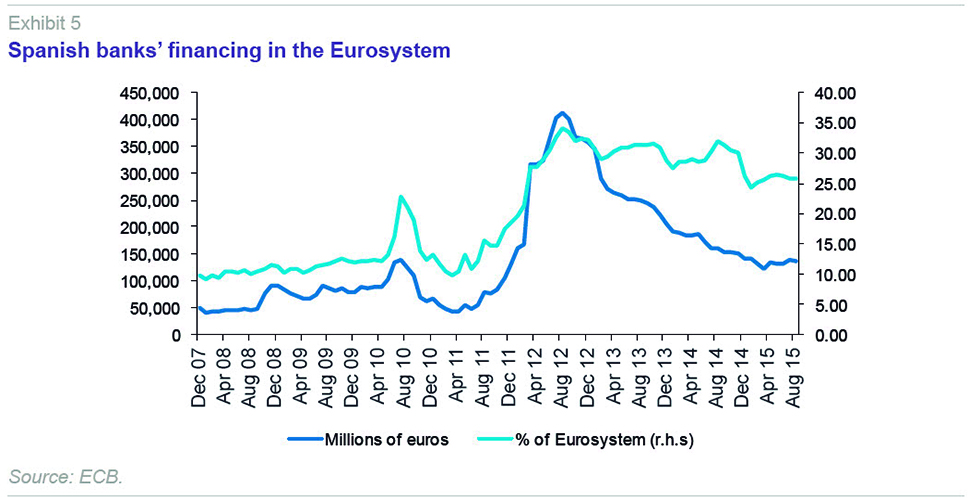

The problems accessing wholesale markets when the crisis broke out, further exacerbated by the sovereign-debt crisis, forced Spanish banks to resort to ECB liquidity on a large scale. The low interest rates charged on this type of funding also made it particularly attractive. As Exhibit 5 shows, Eurosystem financing peaked at 411 billion euros in August 2012, at precisely the moment Spain requested financial assistance from the European Union at the height of tensions. From this high point, when the Spanish banking system accounted for 34% of the ECB’s gross total lending, its dependence has dropped by a third, currently at 138 billion euros. This is nevertheless a large share of Eurosystem funding (26%).

Asset quality

The quality of Spanish banks’ assets deteriorated progressively as the property-market bubble burst, given the high concentration of risks in property-related activities (construction, property development, and mortgages). As already discussed, lending to this sector peaked at 61.5% of total credit to the resident private sector, and subsequently dropped to around 55% in mid-2015. However, construction and property development, the area of activity hardest hit by the crisis, had dropped from a peak of 27% of lending to around half that (13.6%) by June 2015.

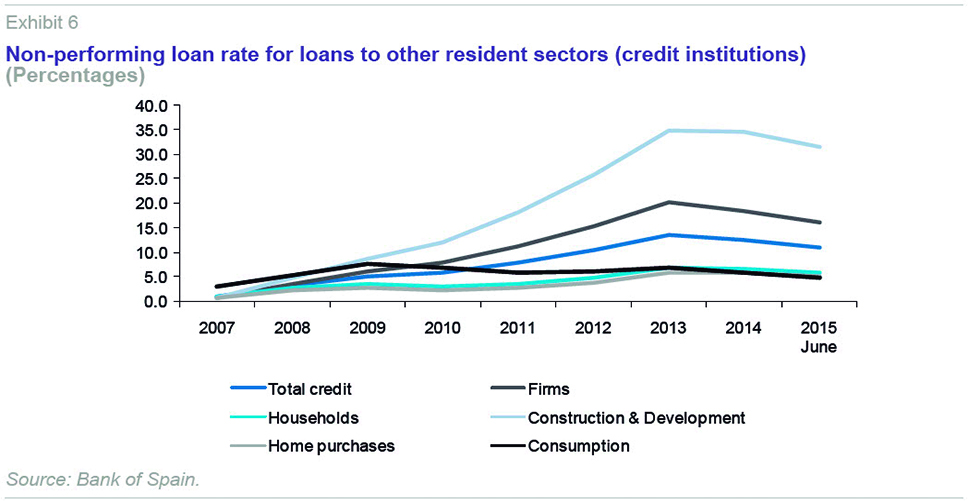

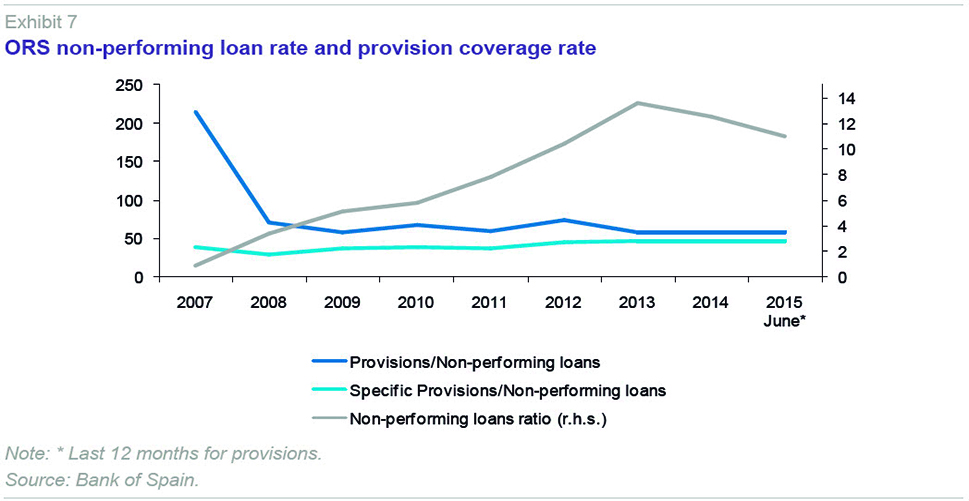

Driven by the economic crisis, the non-performing loan rate rose exponentially between 2007 and 2013 (Exhibit 6). Since its peak at close to 14% it has been falling as the economy has emerged from recession, having dropped to 11% in June 2015. However, this average conceals significant differences across types of credit. In the case of property development and construction, non-performing loans reached a maximum of 35% in 2013, and although they have since fallen, the rate remains high (31.5%). By contrast, non-performing loans for housing purchases currently comprise 5.3% of the total. The non-performing loan rate on all types of loans has been falling continuously since January 2014, with doubtful loans valued at 147 billion euros in July 2015, a drop of 26% (50 billion euros) from the peak. At present, 39% of non-performing loans are in the property development and construction sectors (58 billion euros). This share rose as high as 51% in 2011.

One factor to bear in mind regarding doubtful assets is their provision coverage. After a sharp drop in the coverage ratio in 2008 as a result of the increase in non-performing loans, the ratio is currently 58%. In the case of specific provisions, coverage has been rising since 2011, and in June 2015 it was 47%.

Solvency

In the years of expansion up until 2007, Spanish banks’ own funds grew more slowly than assets, with the result that proportionally they fell from 6.4% of assets in 2000 to 5.9% in 2007 (Exhibit 8). This drop continued until 2010 (5.7%). Since then the ratio has gradually increased, rising to a new high of 7.9% in June 2015. The leverage ratio has fallen since 2010, when it was 17.6, to 12.7 in June 2015. This represents a significant capitalisation effort, and has allowed the Spanish banking system to meet the requirements of the MoU and the new capital requirements under Basel III. In particular, Spanish deposit-taking institutions’ solvency ratio at June 2015 was 14.3% and the common equity tier 1 capital ratio (CET1) was 12.4%. Both these values are above the minimum required (8% and 6%, respectively). There has also been an improvement in the quality of capital, as 87% of the total is top quality capital (CET1).

Efficiency and costs

In a context of low interest rates and narrow margins, and with a declining volume of assets due to the deleveraging of the economy, it is essential that banks rationalise their costs in order to improve their efficiency. Although banks gained efficiency during the expansion thanks to a sharp drop in operating expenses (which fell by 43% as a percentage of assets), current efficiency levels (Exhibit 9) are below pre-crisis levels as a result of gross margins shrinking faster than operating expenses. The current efficiency ratio is therefore 48.5%, 5.2 pp worse than in 2007. Consequently, despite the correction in overcapacity, with the closure of more than 14,000 branches (a cut of 31%) and a cut in employment of 70,000 (25%) since the peak in 2008 (Exhibit 10), the sharp drop in banks’ margins has meant this effort has been insufficient to achieve efficiency gains.

In terms of recurrent efficiency (eliminating earnings from financial transactions), the trend was similar up until 2012 but differed in subsequent years due to the increased share of this type of non-recurrent revenues. This efficiency ratio is currently 8.2 pp higher (meaning efficiency is lower) than in 2007. It deteriorated sharply in 2013 (increasing by almost 11 pp) and only managed to improve by 2.8 pp in 2014 and 2015, ending the period at 55.9%, which is close to the 2014 level.

Challenges facing the Spanish banking sector

The recent evolution of the Spanish banking sector shows a return to profitability after the enormous impact of the crisis, which required write-offs equivalent to 27% of GDP, and caused the sector to post negative returns in 2011 and 2012. Correcting the imbalances that built up during the expansion has required a profound restructuring that has manifest itself in the shedding of overcapacity and the consolidation of the sector.

Although the restructuring and write-offs have made public aid necessary (largely financed from the European bail-out funds), the level of aid is similar to the European average (between 2008 and 2014 the cumulative aid was equivalent to 5% of Spanish GDP, compared with 4.7% in the eurozone as a whole), although, unfortunately, the impact on the public deficit has been bigger in Spain (4.4% of GDP compared with 1.8% in the eurozone as a whole).

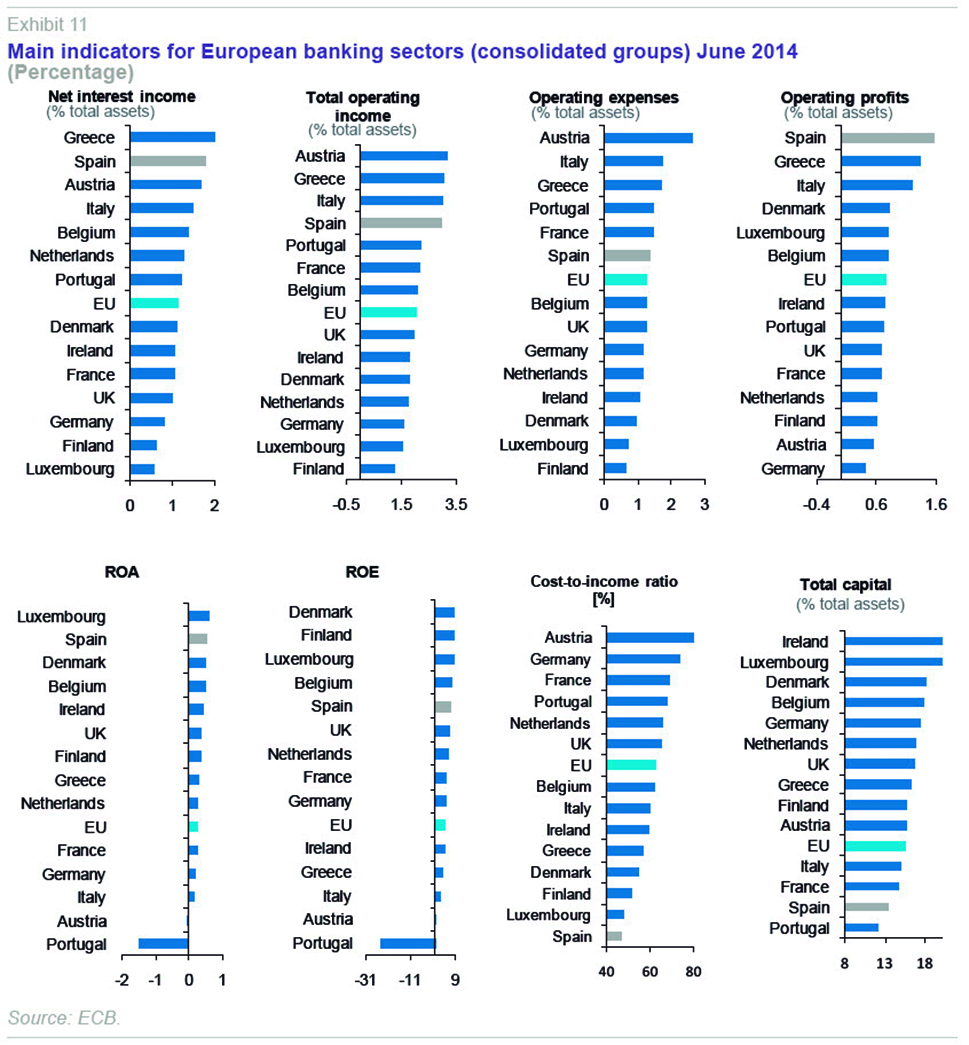

The adjustment has allowed the Spanish banking system to become well positioned on the ranking of EU banking sectors in terms of profitability and efficiency. The latest comparable data from the ECB’s statistics refer to June 2014 at the consolidated group level. As Exhibit 11 shows, the Spanish banking system enjoys high net interest and operating margins, its operating expenses per unit of assets are similar to the European average, it tops the ranking among the main EU countries in terms of operating margins, its profitability is above the European average, and it is the most efficient in the group of countries analysed. The Spanish banking sectors´ poorest performance is on the solvency ratio, with a value 2.2 points below the average for the EU’s banks. However, this indicator should be interpreted with caution given the differences in the way risk-weighted assets are measured.

Although the banking crisis is now behind us, current profitability levels are low and are a long way short of pre-crisis levels. The sector’s average ROE is currently 5.9%, a low and insufficient level relative to the cost of attracting capital (around 8%, according to some recent estimates). This problem is not unique to Spanish banks, as according to the IMF’s latest financial stability report, dated October 2015, the ROE of banks in developed countries has fallen from 13.2% over the period 2000-06 to 8.2% in 2014. In 2014, Eurozone banks’ ROE was around 2.5%, compared with 9% in North America. Almost 70% of the drop in profitability in developed countries is due to stricter capital requirements. The eurozone banks’ lower profitability is due to their large volume of non-performing assets.

In this context, one of the biggest challenges facing the Spanish banking system is to raise its profitability. This is far from easy in an environment of low interest rates, which are damping the recovery in margins, and increased regulatory pressure, with stricter capital requirements. Although net interest income rose slightly in 2014 and the first half of 2015 as financial costs fell more than income, if the benchmark rates in the money markets remain at their current levels, they will have a negative impact on margins, as although there may be scope for lower lending rates (which continue to drop as a result of more intense competition), the same is not true for borrowing rates.

The key variable in this scenario becomes efficiency. And improving efficiency will mean cutting costs. However, as we have seen, despite the intense correction to overcapacity, costs per unit of assets have barely dropped, and indeed have increased since 2012. Spanish banks therefore need to continue rationalising costs, which could encourage (as the ECB and Bank of Spain have recently suggested) further mergers as banks aim for economies of scale in order to reduce their costs. In parallel, progress developing on-line and mobile banking is an essential part of cost cutting, although the benefits will not materialise in the short term. In any event, other channels offering an alternative to traditional branches as a means of accessing banking services should be given more importance. This is particularly relevant in Spain’s case, given that it has Europe’s densest branch network and smallest average branch size.

One of the lessons of the banking crisis in Spain has been the importance of geographical diversification. Spain’s two largest banking groups have weathered the storm best not only thanks to sound management, but also because of the advantages of diversification. The basic principle that “diversification reduces risk” has been reflected faithfully in the bottom line of Spain’s two largest banking groups. Therefore, the new banking groups that have emerged in Spain out of the restructuring, and those that may emerge from future mergers, should look to expand internationally, particularly bearing in mind that business in Spain is likely to be sluggish for some time as a result of the deleveraging still underway.

Another vulnerability is the large volume of non-performing assets. This is a problem that has been highlighted by the IMF in its latest report on the European banking sector. Spanish banks have bad loans valued at around 14% of GDP on their balance sheets. However, if foreclosed assets are also considered, the figure rises to 22% (230 billion euros). These are assets that generate costs but no income, thus weighing down profitability.

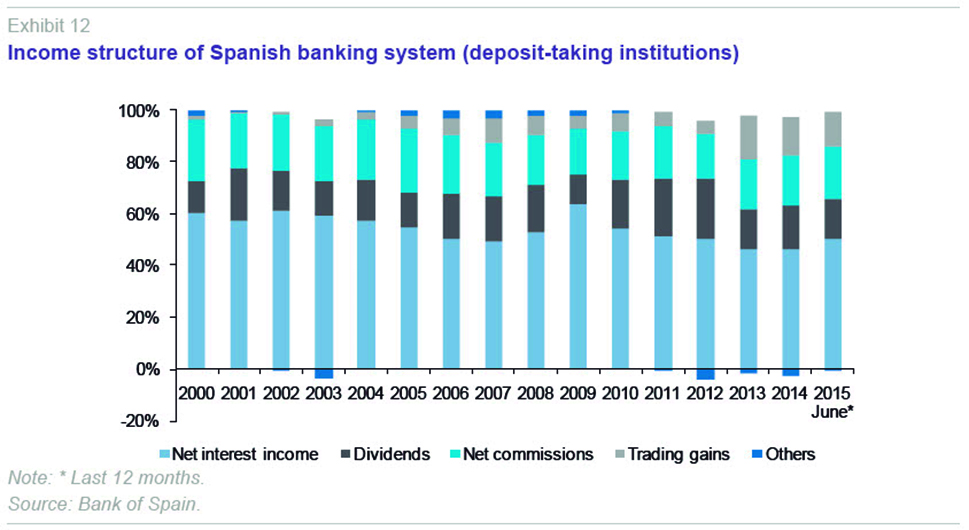

One additional challenge the Spanish banking system faces derives from the change in income structure. During the credit boom, when margins were high, net interest income accounted for as much as 64% of total net income. With the drop in credit and narrowing of margins, banks used earnings on financial transactions as an escape valve, such that they accounted for 18% of net income in 2013 (Exhibit 12). Earnings were also shored up by the capital gains obtained from the carry trade, whereby they used the lower interest rates from the ECB to finance public debt purchases. As this type of income is non-recurrent, banks face the challenge of maintaining their income in an environment in which low interest rates mean they will not be able to repeat these capital gains. In fact, over the twelve months to June 2015, the contribution had dropped to 13%.

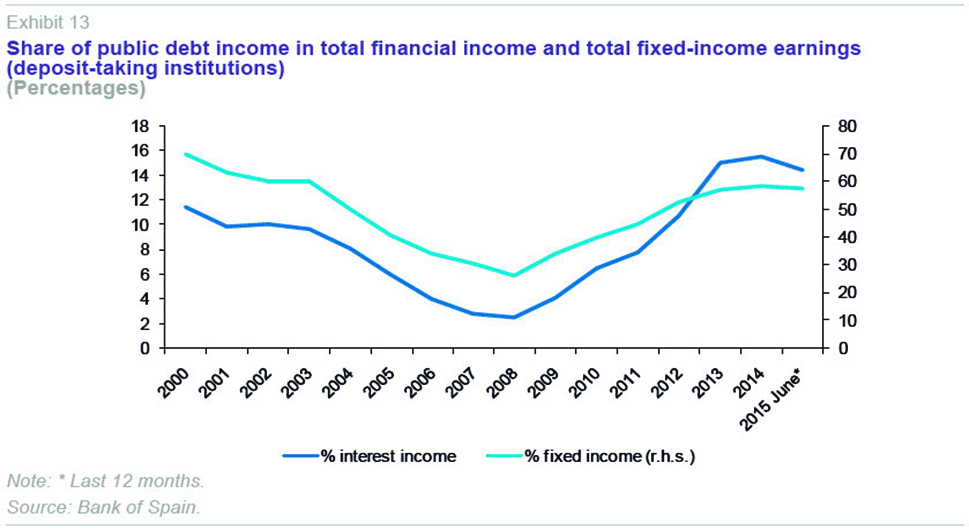

The carry trade also boosted Spanish banks’ bottom lines with the income obtained from buying public debt, particularly when interest rates on public debt were high. In 2007, the income associated with public debt represented 2.7% of the Spanish banking system’s total financial income and 30% of income from fixed-income securities (Exhibit 13). In 2013 and 2014, following the ECB’s opening up its liquidity facility, the percentage reached a maximum of 15.5% (58% of fixed income). High levels were maintained over the 12 months to June 2015 (14.4% of total financial income and 58% of fixed-income earnings).

In summary, although the banking crisis is now behind us, as the reactivation of new lending and recovery in profitability show, the sector’s challenges and vulnerabilities suggest that, going forward, it will be difficult to boost profitability. This requires institutions to continue raising their efficiency and exploring new business models, while reflecting on the future viability of the current retail banking model based on an extensive network of branches that are too small by European standards.

Note

This article was written as part of the Ministry of Science and Innovation SEC213-43958-R and Generalitat Valenciana PROMETEOII/20147046 research projects.

Joaquín Maudos. Professor of Economic Analysis at the University of Valencia, Deputy Director of Research at Ivie and collaborator with CUNEF