Credit, deleveraging, and financial savings: Balancing adjustment and recovery in Spain

Spain is among the countries having made most progress on deleveraging since 2010. Debt reduction efforts are expected to be compatible with private sector credit growth and positive savings rates in 2016, in line with the trend for the Spanish economy as a whole since 2012.

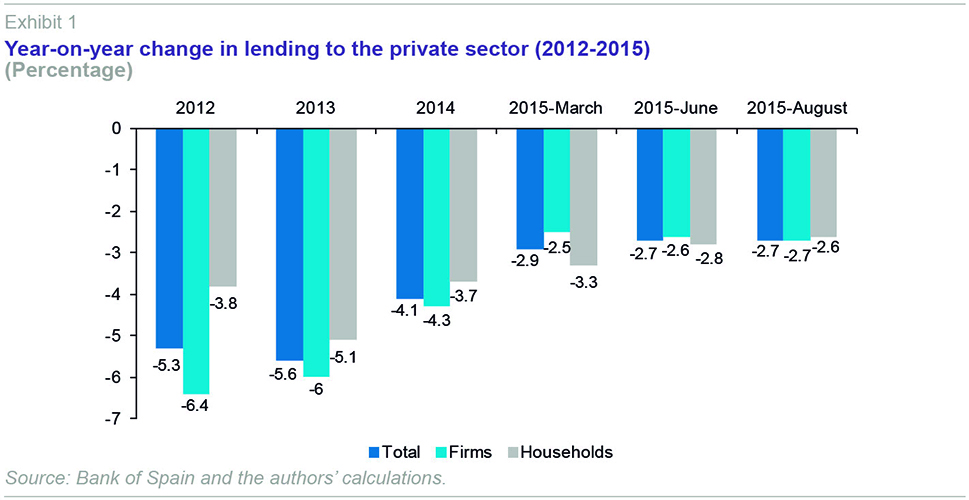

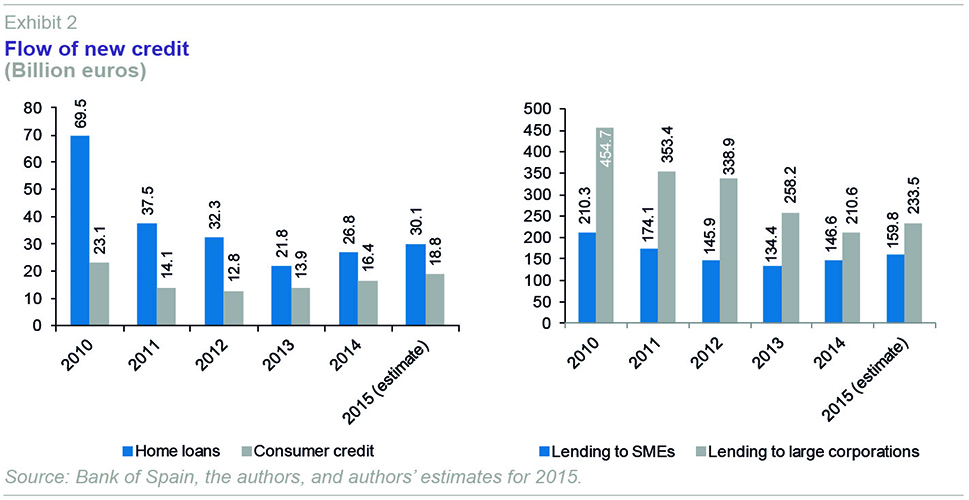

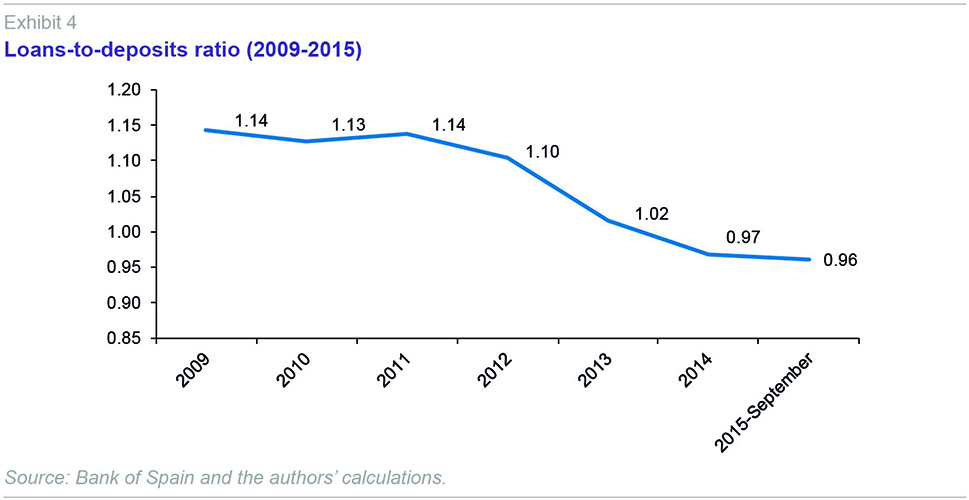

Abstract: The process of deleveraging in Spain has been compatible with an increase in new lending flows and a gradual recovery in financial savings. While the rate of change of the stock of credit remains negative, for the private sector as a whole, it has dropped from -5.3% in 2012 to -2.7% in August 2015. This transition was from -6.4% to -2.7% for firms and -3.8% to -2.6% for households. In the case of new lending to firms, credit to SMEs stood at 146.6 billion euros in 2014, and it is estimated at 159.8 billion euros by year-end 2015. These readjustments have been compatible with the reduction of the debt burden, as shown by the evolution of the private sector loans-to-deposits ratio, a proxy for deleveraging, which was 1.14 in 2009, but has dropped in recent years to as low as 0.96. Between 2010 and June 2015, households and firms reduced their debt by 450 billion euros, or 37.5 percentage points of GDP. At the same time, financial savings has gone from negative values in almost all sectors before the crisis to an increase of up to 2% for the country as a whole in June 2015 (3.8% for households and 1.5% for firms).

Introduction: Deleveraging, savings, and long-term growth

There was a considerable build-up of private debt in the years preceding the crisis in Spain. Leveraging continued up until 2010. Since then, households and firms have taken measures to reduce their debt considerably, albeit through different ways and with different intensities, and these efforts will continue for several more years. However, although necessary, this deleveraging implies an opportunity cost in terms of the financial resources channelled away from consumption or investment. There is also a risk that it may compromise households’ financial savings, particularly when taking place at a time of high unemployment, as is the case in Spain.

In any event, as this article aims to show, a reduction in debt levels can be compatible with an increase in new lending flows and a gradual recovery in financial savings. For example, in Spain, households and firms are reducing high accumulated debt burdens without having to resort to measures, which could lead to reputational damage for the country, such as write-downs. The problems associated with deleveraging are, however, not unique to Spain nor to this crisis.

Like other components of the economy, deleveraging has, at times, behaved cyclically. A recent International Monetary Fund document (Chen et al., 2015), reviews experiences of debt reduction in 36 advanced economies since 1960. It considers the impact of debt, both during the accumulation phase and when it is necessary to reduce it. The results suggest that a gradual deleveraging of the private sector after recessions is positively and significantly related to substantial medium and long-term GDP growth gains. Also, all the policies geared towards facilitating this effort tend to have a positive effect.

In countries such as the United States, at the peak of the crisis, some studies (Glick and Lansing, 2009) suggested that to reach a “reasonable” level of private debt, a ten-year adjustment would be necessary in which the savings rate would need to increase from 4% in 2009 to 10% in 2018. This savings would imply a reduction of 0.75% in the annual rate of consumption growth, which would hold back economic recovery, but would ensure more sustainable growth over the long-term.

However, when the United States began to emerge from the crisis, studies (Bauer and Nash, 2012) pointed out that although in theory, deleveraging could have negative effects on consumption, U.S. households held back from increasing consumption significantly when they began to have more disposable income. This suggests that factors other than deleveraging, linked to expectations or the quality of employment, may also be important for the recovery.

Similar results have been observed in some European economies particularly affected by property crises and problems associated with debt levels. This is the case in Ireland, where McCarthy and McQuinn (2014) use mortgage data to show that households have difficulties meeting their payments in the wake of the crisis, which entails a significant reduction in consumption, although they also suggest positive effects over the long-term.

Financing conditions and credit

The ability to repay debt, save, or extend new credit largely depends on the macroeconomic situation and financial conditions (primarily the level of uncertainty and interest rates).

The recent press release from the Governing Council of the European Central Bank on October 22

nd, 2015

[1] stated that “while euro area domestic demand remains resilient, concerns over growth prospects in emerging markets and possible repercussions for the economy from developments in financial and commodity markets continue to signal downside risks to the outlook for growth and inflation.” The ECB went on to say that, although monetary policy was already quite loose, it would probably be necessary to re-examine this “degree of accommodation” at the monetary policy meeting in December. Furthermore, according to the ECB, it “is willing and able to act by using all the instruments available within its mandate if warranted in order to maintain an appropriate degree of monetary accommodation.” The ECB estimates that inflation in the euro area will rise in 2016, but will remain short of the medium-term target of 2%.

This monetary context, however, implies relatively favourable lending conditions. Indeed, the ECB has observed that the year-on-year rate of change in lending to non-financial corporations (adjusted for sales and securitisations) in the euro area rose to 0.4% in August, following the figure of 0.3% in July. However, the ECB acknowledges that “despite these improvements, developments in loans to enterprises continue to reflect the lagged relationship with the business cycle, credit risk, credit supply factors, and the ongoing adjustment of financial and non-financial sector balance sheets.”

On the objective of completing the financial adjustments in the euro area (including deleveraging), the ECB was keen to point out that the monetary policy target is to maintain price stability, but that “in order to reap the full benefits from our monetary policy measures, other policy areas must contribute decisively [...] In particular, actions to improve the business environment.”

The improvement in costs and conditions of access to finance is also perceptible in Spain, as may be deduced from the latest

“Encuesta de préstamos bancarios” [Bank loan survey] published by the Bank of Spain in its October Economic Bulletin.

[2] This survey suggests that lending criteria were relaxed slightly in the case of lending to households to buy residential property in Spain for the first time since 2006, while they became slightly stricter in the euro area. On the demand side, both national and euro area institutions reported an increase in the number of loan applications from households for home purchases, consumption and other purposes in the third quarter. Interestingly, Spanish financial institutions stated that they perceived an improvement in conditions of access to both retail finance and wholesale markets. This was also perceptible in the euro area average. They also indicated that the ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme improved their financial situation over the last six months, with this effect being stronger in the case of Spanish institutions. By contrast, the impact on approval criteria in Spain was negligible. In any event, Spanish banks stated that they used the liquidity from the programme mainly to extend credit, and to a lesser extent to substitute for other funding sources.

Another significant factor in relation to financial conditions is the perception of the country’s solvency and stability, as expressed by the rating agencies. In October, Standard & Poor’s raised Spain’s rating a notch from ‘BBB’ to ‘BBB+’ with a stable outlook, and highlighted the “positive impact of the reforms on the economy.” On October 21st, Fitch published its “Fundamental Index” for Spain, which is a report on the state of credit and financial conditions. Fitch stressed the improvement in the supply and demand for credit, and above all, highlighted the flow of lending to SMEs (as will be discussed below). On October 23rd, Fitch affirmed Spain’s rating as “BBB+,” also with a stable outlook, pointing to an improvement in the country’s financing costs and, in general, a reduction in systemic risks.

As regards recent trends in credit in Spain, Exhibit 1 shows the year-on-year change in credit to the private sector from 2012 to August 2015. The rates remain negative, although for the sector as a whole the rate had dropped from 5.3% in 2012 to 2.7% in August 2015, 6.4% to 2.7% for firms and 3.8% to 2.6% for households. In any event, few analysts expect a return to positive figures before 2016.

Debt repayments still appear to be a bigger factor in the change in credit than new lending flows. Even so, there has been a gradual recovery in new credit, as can be seen from Exhibit 2, which shows the progress since 2010 and an estimate for year-end 2015 (based on the flows observed up until September). In the case of domestic economies (left pane of the Exhibit), home loans rose from 26.8 billion euros in 2014 to 30.1 billion euros in 2015, while consumer credit rose from 16.4 billion euros to 18.8 billion euros over the same period. These figures suggest gradual progress, but are still a long way short of the 69.5 and 23.1 billion euros of credit for housing and consumption, respectively, in 2010.

In the case of new lending to firms (right pane of Exhibit 2), credit to SMEs (using transactions valued less than one million euros as a proxy) came to 146.6 billion euros in 2014, and it is estimated that it will end 2015 at 159.8 billion euros. This figure still contrasts with the figure of 210.3 billion in 2010. In the case of large enterprises, new credit in 2014 came to 210.6 billion euros in 2014 and is expected to rise to 233.5 billion euros in 2015. However, large enterprises seem to be making a bigger effort to pay down debt, as the volume of transactions in 2010 was 454.7 billion euros.

Both the flows and the cost of this private sector financing have improved. Thus, the Bank of Spain’s October Economic Bulletin reported that “interest rates on new credit to non-financial corporations fell in August compared to the previous month by 31 basis points (bp) in the case of transactions for a value of over a million euros (to 1.8%) and just 1 bp for smaller transactions (to 3.7%).”

Deleveraging effort

“Deleveraging” has been one of the most frequently used terms in reports on Spain in recent years. It is generally understood to be a necessary rebalancing that demands short-term sacrifices but supports long-term growth. In a recent speech,

[3] the governor of the Bank of Spain said that “debt-to-GDP ratios of both non-financial corporations and households continued to moderate and are well below the peaks reached in 2010 during the previous cycle, thus narrowing the gap between Spain and the average debt-to-GDP ratios in the Economic and Monetary Union countries. For the euro area as a whole, the gradual improvement in aggregate credit has continued, with an increase, albeit moderate, in loans extended both to financial corporations and households. The ongoing relaxing of loan approval criteria is also perceptible across the euro area as a whole, except in the case of stricter criteria for home loans, due to the regulatory changes approved in a number of countries.”

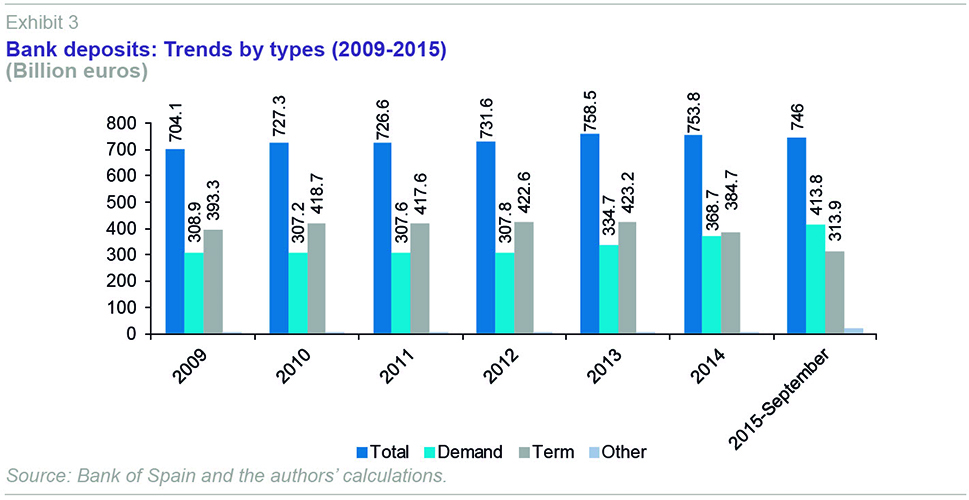

An initial perspective is given by the household sector liquidity reference, for which bank deposits are a proxy. Deposits have behaved erratically since 2009, although since 2013 they have stabilised at around 750 billion euros, as against 704.1 billion euros in 2009 (Exhibit 3). What is most striking, however, is the change in composition, as demand deposits have increased, while term deposits have declined. This is partly due to the competition between deposit-taking institutions, offering attractive demand deposit rates to capture liquidity.

Even though it is an imperfect indicator, one of the most commonly used measures to approximate the private sector’s leverage is the loans-to-deposits ratio. Exhibit 4 shows how this ratio was above unity in 2009 (1.14) but dropped to 0.96 in subsequent years, mainly as a result of debt reduction efforts.

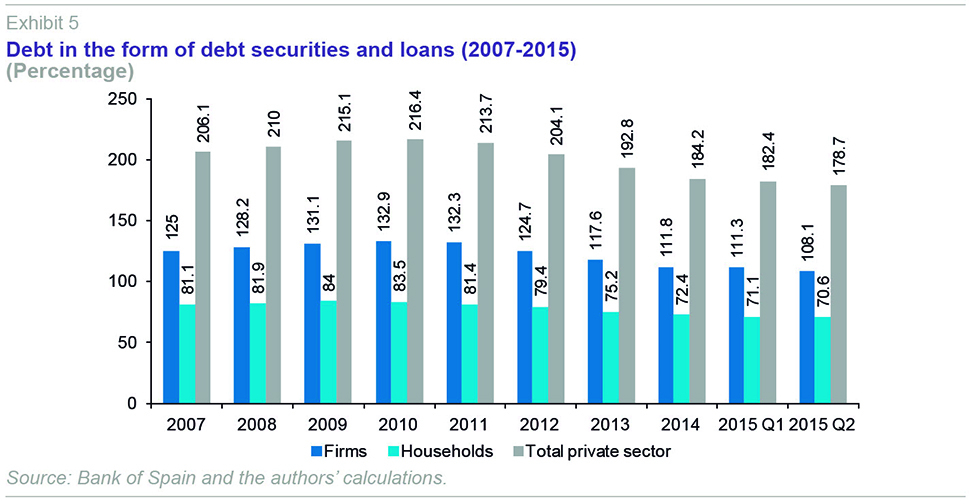

Just how much have households and firms reduced debt? Exhibit 5 shows the progress of debt in the form of debt securities and loans between 2007 and 2015. According to data from the Bank of Spain’s Financial Accounts of the Spanish Economy, this ratio represented 206.1% of GDP for the private sector as a whole in 2007, rising to 216.4% in 2010, before dropping back to 178.7% in the second quarter of 2015. Households’ debt-to-GDP ratio reached 83.5% in 2010, but had dropped to 70.6% in the second quarter of 2015. Firms’ leverage dropped from 132.9% to 108.1% of GDP over this same period.

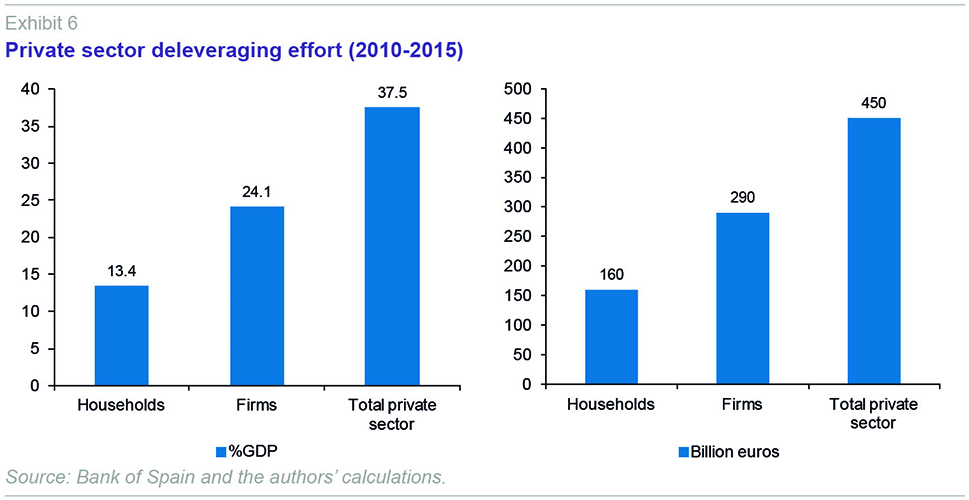

Exhibit 6 summarises progress on deleveraging. Between 2010 and June 2015, households and firms had reduced their debt by 450 billion euros, or 37.5 percentage points of GDP (households by 160 billion euros and firms by 290 billion euros). With this rate of deleveraging, in its monthly report for investors,

[4] the government estimates that the ratio of household debt to GDP will be in line with that in Germany and France in 2018, and that the outstanding mortgage lending balance will be half of current levels between 2020 and 2023.

Savings and financial wealth (2007-2015)

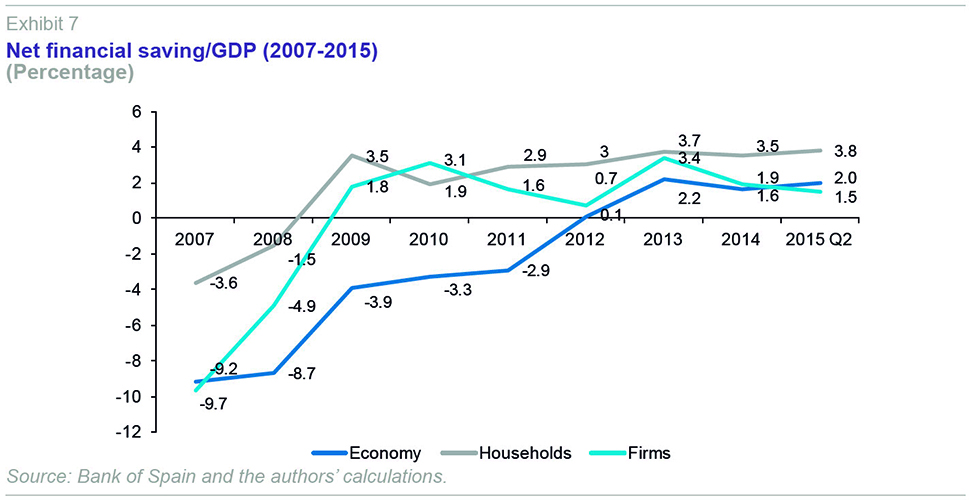

Under the financing and debt conditions described, how have the private sector’s financial saving progressed? The first part of the answer may be found in Exhibit 7, which shows the net financial transactions to GDP ratio, or net financial savings. This rate has gone from negative values in almost all sectors before the crisis to an increase of up to 2% for the country as a whole in June 2015 (3.8% for households and 1.5% for firms).

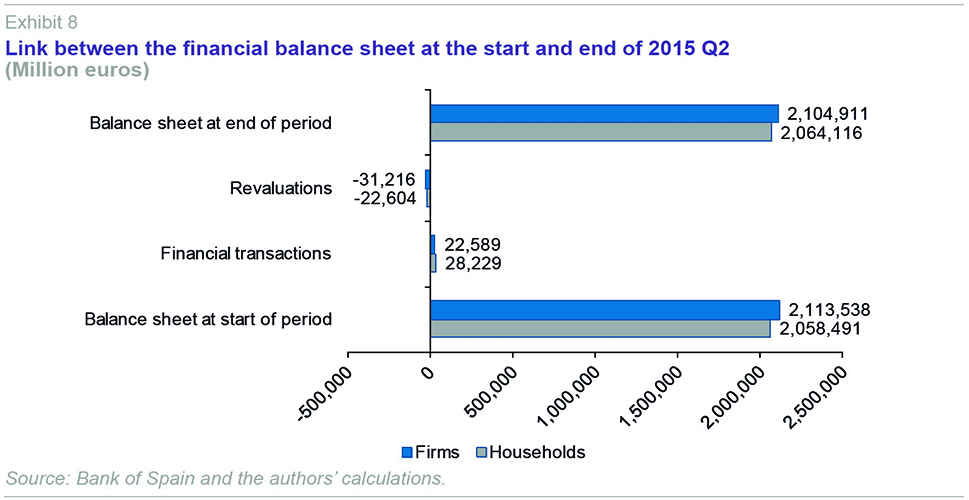

This trend is a result of several factors, such as improved market conditions (it is worth recalling that assets are valued at market prices in the financial accounts) and increased disposable income since 2013. Exhibit 8 can be used to examine what recent factors are encouraging improvements in net financial saving, among both households and firms. The exhibit shows the balance at the start and end of the second quarter of 2015. Despite an unfavourable quarter for the market, with firms’ assets depreciating by 31,216 million euros and households’ assets losing 22,605 million euros, volume transactions grew by around 50 billion euros across the private sector as a whole, allowing households’ and firms’ financial balance sheets to remain over 2.06 trillion and 2.11 trillion euros in June 2015, respectively.

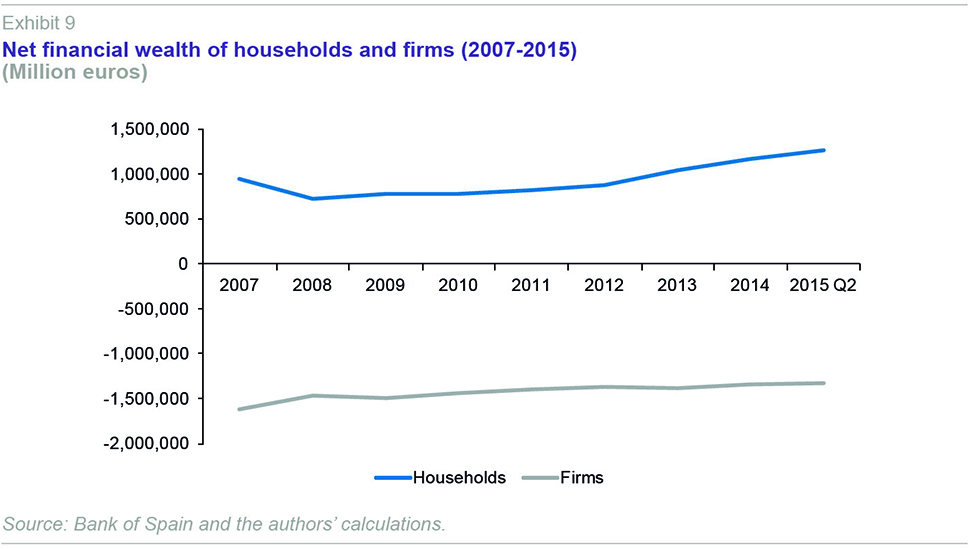

In any event, more than the recovery in assets, what has improved the situation of the private sector has been firms’ debt reduction, as discussed above. In particular, in June 2015 households had achieved net financial wealth (financial assets less liabilities on their balance sheet) of 1.26 trillion euros, compared with 0.72 trillion in 2008. In the case of firms, their net financial balance is negative given their higher debt level, but it has gone from -1.49 trillion in 2010 to -1.33 trillion in June 2015.

In short, the data presented here show that Spain’s deleveraging effort has been significant, and is compatible with a gradual recovery in new lending flows and financial saving. These are rebalancing mechanisms in which debt repayment still outweighs new lending, but all the signs suggest that 2016 may be the year in which the tide turns and the opposite starts to be true.

Notes

References

BAUER, R. A., and B. J. NASH (2012), "Where Are Households in the Deleveraging Cycle?," Economy in Brief, Nº 12-01, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

CHEN, S.; MINSUK, K.; OTTE, M.; WISEMAN, K., and A. ZDZIENICKA (2015), Private Sector Deleveraging and Growth Following Busts, WP/15/35, International Monetary Fund.

GLICK, R., and K. J. LANSING (2009), U.S. Household Deleveraging and Future Consumption Growth, FRBSF Economic Letter.

MCCARTHY, Y., and K. MCQUINN (2014), Deleveraging in a highly indebted property market: Who does it and are there implications for household consumption?, Research Technical Paper 05/RT/14, Central Bank of Ireland.

Santiago Carbó Valverde. Bangor Business School and FUNCAS

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and FUNCAS