Recent trends in Spain´s private equity market

Despite a somewhat slow start, in 2017, Spain’s private equity market experienced record levels of investment and a recovery in fundraising activity since the crisis. Nevertheless, increased competition will present challenges for the sector going forward.

Abstract: Private equity is good for breathing life into the business landscape and fostering innovation. Although this financing instrument has been around for a long time, its development in Spain has lagged somewhat as a result of both cultural factors and the timing of the creation of a regulatory framework propitious to its development. Having originated in the public sector, with a focus on facilitating investment in SMEs, the private equity sector has evolved substantially and today, the majority of private equity investors come from the private sector, with international funds playing an increasingly prominent role. This ability to attract investment from abroad, against the backdrop of economic growth, led to growth in investment volumes to an all-time high in 2017. Moreover, the existence of favourable financing conditions, on offer from banks and non traditional financiers alike, is helping to get transactions closed.

Introduction

The private equity business has been regulated in Spain since 1986, although it was not until 1999 that a specific legal regime for entities providing this form of financing was developed. Subsequently, between 2005 and 2014, the regulatory framework was updated and made more flexible with the aim of addressing the shortcomings that were impeding the sector’s growth.

Private equity entities (firms and funds) are investment vehicles whose core business is to take temporary equity interests in companies other than financial institutions or real estate companies. To achieve their purpose, they can provide profit-participating loans and other forms of financing to their investees along with advisory services.

This form of financing offers companies fl solutions, specifi capital to fund their growth plans, develop innovative new projects, acquire other companies or restructure their capital. Private equity investors usually add value to their investees by injecting credibility vis-à-vis third parties as well as by sharing their experience, expertise and contacts.

Three key measures are used to track the private equity business: (i) investment volumes; (ii) fundraising; and, (iii) exit volumes.

Investment

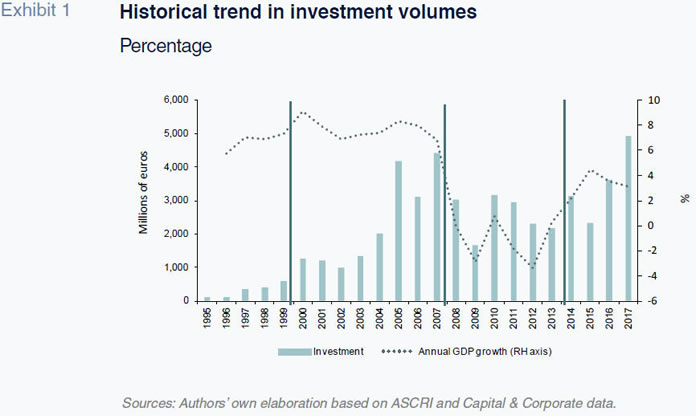

Analysing the trend in investment volumes, it is possible to distinguish between four major stages of development in Spain. Firstly, the development period, from 1986 to 1999, which culminated with the creation of a comprehensive legal framework for the private equity business. During this period, private equity investment volumes were scant and almost entirely confined to public investment.

It was followed by what can be termed the take-off period, from 2001 to 2007, marked by sharp growth in investment activity, particularly from 2005, when strong economic momentum coincided with a fresh regulatory reform to fuel annual investment volumes of over 4 billion euros.

The sector was affected considerably by the recessionary period, from 2008 to 2013, years in which investment volumes and fundraising plummeted. As we will show later on, the reduced investment dynamism those years was also attributable to the decisions taken by many funds to delay their exit strategies until the crisis had reverted.

Lastly, we have the growth recovery period, from 2014 to 2017 (ongoing), which started with a new reform of the regulatory landscape in 2014 with the aim of incentivizing fundraising and balanced growth by fostering investment in companies at an earlier stage of development (seed or venture capital). This period has culminated – to date – with a record year for Spain’s private equity industry: investment volumes reached close to 5 billion euros in 2017.

Several factors explain the very positive trend in investment volumes in recent years, including the prevailing, low interest rate environment, coupled with ample liquidity, which, in the context of economic growth, have drawn international investors to the country. In addition, the presence of these international funds has triggered the return to the market of the so-called mega deals – sized at over 100 million euros –, while the middle market (deal size: between 10 and 100 million euros) has also remained very active.

According to data provided by Spain’s private equity association, ASCRI, in 2016, international funds accounted for 71.9% of all investment in Spain, investing 2.6 billion euros, 75% of which classified as ‘mega deals’, 20% as middle market deals and the remaining 5% as deals sized 10 million euros or less. By number of transactions, however, most of the deals (82%) entailed investment of less than one million euros.

In addition, some of the positive trend in private equity in recent years is attributable to greater acceptance of this form of financing on the part of Spanish companies. In the wake of the recent crisis, many firms realized the importance of equity in their capital structure in reducing their dependence on external sources of financing. Indeed, a recent study by Harvard University shows that the companies backed by private equity funds received higher flows of debt and equity in the period immediately following the crisis and therefore were able to post higher rates of growth than the companies that did not have such backing.

As for the destination of investment flows during the various periods, growth and mature companies have traditionally received the most money from private equity firms. Nevertheless, funds focused on seed and venture capital have proliferated in recent years thanks to the recovery in valuations, regulatory support for these kinds of investments, investor appetite for new projects with a technological slant and the start-up of multi-sector incubators and accelerators at the regional level.

This momentum in venture capital is particularly relevant in an economy such as Spain’s in which SMEs play such a dominate role in the business landscape. Despite their importance for economic growth, SMEs have more limited access to financing than larger enterprises and, as was evidenced recently, are more aff by episodes of recession and credit contraction.

These differences even starker in the case of innovative start-ups, towards which the banks are more risk averse. For these companies, venture capital funds are sometimes the only external source of financing and a necessary ally in enabling them to invest sufficiently in innovation and R&D so as to launch their products and services onto the market quickly enough to guarantee their survival.

Moreover, private equity managers are highly experienced at generating economies of scale and bring a deep network of contacts when it comes to looking for strategic partners; they also offer financial and strategic advice needed for subsequent investment rounds, helping to accelerate their development.

According to a recent study by the European Commission, the SMEs that have benefitted from private equity financing are characterised by:

- Faster growth relative to other start-ups or SMEs.

- A higher rate of survival and greater scope for international expansion.

- A high level of innovation, not only in terms of the products and services offered but also in organisational and process terms.

Looking at this last point in more depth, private equity favours innovation thanks to the firms’ ability to carry out R&D activities and advise their investees on processes such as patent applications. Elsewhere, within venture capital funds’ investment strategy it is worth highlighting their strategic focus on innovative companies: support for innovation is somewhat intrinsic to venture capital.

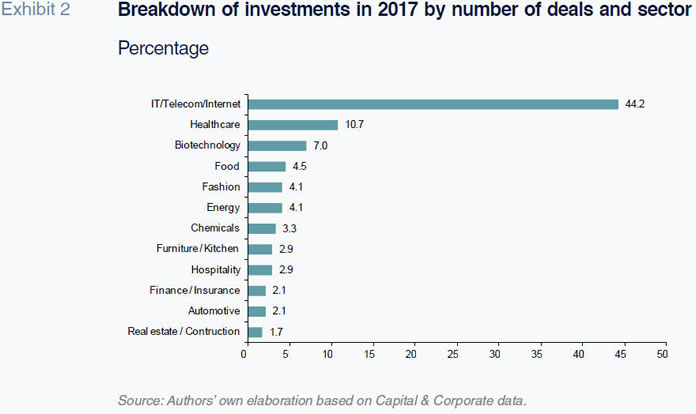

From a sector standpoint, once again looking at the private equity sector as a whole, there is a preference in terms of the number of deals closed for companies with a presence in the technology and internet sectors. These sectors offer private equity firms the opportunity to generate high returns and the scope for helping to create value at the companies themselves. As shown in the breakdown of the allocation of investments by sector provided in Exhibit 2, in 2017, over half of the transactions recorded took place in the internet, telecommunications and IT sectors, followed by healthcare (a share of 10.7%), biotechnology (7.0%) and food (4.5%).

Because these companies tend to be small- sized start-ups, unit investment in technology companies is relatively smaller than the transactions closed in other sectors. Even so, looking at the breakdown of investments by value, the telecommunications and IT sectors received the second-highest level of investment in 2016 (18% of total investment that year), ranking only behind the hospitality and leisure sector (25%) and followed by consumer products (10%).

Fundraising

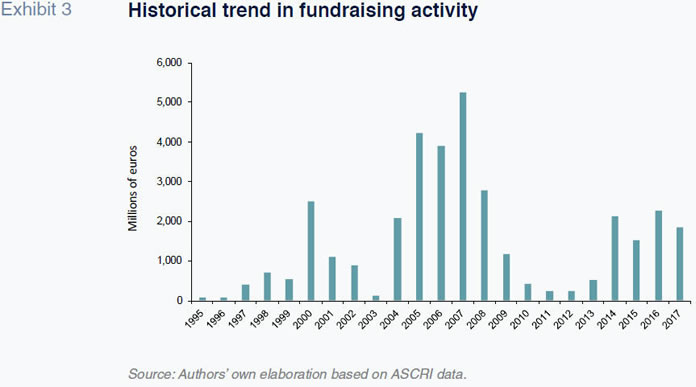

As for the second key metric used to track the private equity sector, namely fundraising activity, the trend in this measure tends to closely mirror the dynamics observed in investment activity and the length of time the funds stay on in their investees (an investment cycle typically of around five years). Looking at the historical trend in this metric, we note that fundraising volumes peaked in 2005 and 2007, remaining broadly constant between 2014 and 2017 (Exhibit 3).

In the last four years, private equity firms have raised 7.8 billion euros in total, compared to 1.45 billion euros between 2010 and 2013. In 2017, they raised 1.86 billion of new funds (2.27 billion euros in 2016) and the expectation is that they will continue to raise money for new funds in 2018 against the backdrop of still-abundant liquidity and scant returns on liquid fixed-income assets, buoyed by continued strong confidence in Spain on the part of international investors.

The momentum in fundraising volumes is reflected in the number of players. According to ASCRI data, 120 new private equity firms were created in Spain between 2000 and 2007, putting the total at the end of that year at 162 entities. At year-end 2016, according to the most recent records of the CNMV, the securities market regulator, the number of entities stood at 292 (up 10% from 2015). As for the new entities set up in 2016 it is worth highlighting two trends: the positive trend in SME private equity vehicles (a format introduced as part of the regulatory reforms of 2014), which went from 14 to 25 in number and whose investment strategy is focused on smaller sized SMEs; and, (ii) the creation of the first European private equity funds that can be marketed in Spain and in other EU members states alike.

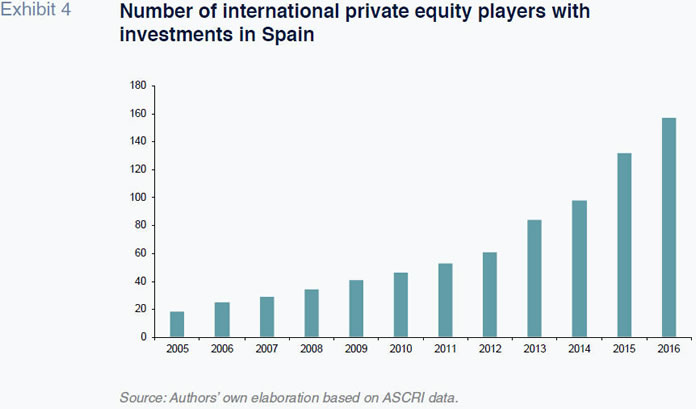

As for the various classes of private equity firms, there have been considerable changes in the sector’s make-up. When the private equity sector took its first steps in Spain 32 years ago, it got going thanks to the public sector. Today, however, it is the private sector private equity firms that totally dominate the landscape. There has also been sustained growth in the presence of international players in Spain, as shown in Exhibit 4.

Lastly, there has also been a shift in the type of investors in these funds, namely a shift away from the banks, which in 1997 accounted for over 40% of the sector’s fundraising, towards a more diversified financing profile populated by a significant number of pension funds, insurance companies and funds of funds (vehicles that do not invest in companies directly but rather buy interests in other funds).

Exits

As for these funds’ exit process, the period of time they remain invested in their investees has lengthened in recent years as a result of the effects of the financial crisis, reaching a record high of seven years on average in 2016. The sector waited for an improvement in the economic cycle so as to maximise exit valuations. As a result, in 2014 and 2015 exit volumes totalled 9.5 billion euros, which is more than in the prior six years together (8.59 billion euros). In 2017, exit volumes increased once again. According to ASCRI, they increased to 3.48 billion euros (divestment volumes are stated at investment cost) from 1.85 billion euros in 2016 (growth of 87.9%).

In terms of the exit routes taken, the most common exit formula in Spain has traditionally been to sell the company either to a trade buyer, the investees’ own management teams (MBO) or another private equity firm, while the role of IPOs has been relatively less significant. This reduced reliance on IPOs in Spain compared to other economies may reflect the size of the investees, in many instances too small to access the continuous market, and the limited liquidity of alternative stock market (the MAB) for growth companies.

As a result, divestments in the form of IPOs represented just 14% of exit volumes in 2016, whereas 57% were accounted for by private sales: 26% by sales to third parties, 18% to management buyouts and 13% to secondary buyouts (sales to other private equity firms).

Price bubble?

The last aspect warranting analysis in terms of the state of play of the private equity market in Spain today is the risk of a transaction price ‘bubble’ that some analysts and players are currently perceiving.

The sharp increase in investment volumes, which as we have noted peaked in 2017, has created a highly competitive environment for the private equity firms operating in Spain, which in some instances are beginning to feel pressure to place the abundant resources raised in prior years. Moreover, competition has intensified as a result of the strong commitment of some of the world’s largest private equity houses, drawn by Spain’s bright economic prospects and instigators of some of the largest transactions closed in recent years.

In addition, the existence of bank financing on highly favourable terms (amount, conditions, cost and collateral requirements), coupled with the advent of alternative financiers, has also spurred deal-making, characterised by growth in leveraged buyouts and resulting in higher debt levels compared to previous years.

This competitive pressure has been evident in numerous transactions to have hit the market in recent months in which we have seen auctions among the entities culminating in the payment of valuation multiples well above those observed in prior years.

In such an environment of high entry- level multiples, the managers’ expertise in generating value from their investees will be more necessary than ever, as the returns they generate for their investors will depend more on their ability to boost profits at their investees than on changes in multiples upon exit.

References

ASCRI (Several years), Venture Capital & Private Equity Activity Reports.

BERNSTEIN, S.; LERNER, J., and F. MEZZANOTTI (2017), Private Equity and Financial Fragility during the Crisis, Harvard Business School.

CAPITAL & CORPORATE (2018), Newsletter, February 2018.

CNMV (2016), Securities Market Annual Report.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2015), Assessing the Potential for EU Investment in Venture Capital and Other Risk Capital Fund of Funds, October 2015.

Irene Peña and Pablo Mañueco. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.