The rental market challenge in Spain

There has been widespread talk of the emergence of a “bubble” in the Spanish rental market, yet underlying data do not support such a theory. Any policy measures adopted to address the increase of market rents in specific cities should carefully assess the potential impact on the overall supply of rentals.

Abstract: It is becoming rather fashionable to describe the dynamics in Spain’s rental markets as exhibiting characteristics of a “bubble”, but close analysis casts doubt on this claim. First, it is necessary to highlight that any analysis of housing market dynamics is restricted both by the limited quality and breadth of available data. Second, while it is true that the financial crisis and subsequent recovery have coincided with a rise in the demand for rental properties, some indicators, such as the rate of severe housing deprivation, in Spain have remained below the EU-28 average, suggesting prices are still relatively affordable. Moreover, there is little empirical evidence to support popular misconceptions as regards the reasons for recent rental price increases, such as the growth of large scale investors as landlords, as well as home sharing platforms. That said, previous public policy measures in this area have failed to adequately address problems in the rental market. Going forward, it will be important to carefully assess the impact of any measures adopted to ensure the incentivisation, rather than restriction, of rental supply, as well as to assess any potential impact on inequality.

Introduction

Recently, a myriad of analysts and media pundits have begun to talk about a “rental market bubble” due to the sharp rise in Spain’s rental prices in some large cities. This widespread concern, coupled with an increase in evictions for non-payment of rent, lead to a Royal Decree-Law outlining amendments to the so-called Urban Lease and Civil Procedure Acts. In fact, one of the reasons Podemos, one of Spain´s left-wing parties, gave for not voting in favour of the state budget was the exclusion of its rent control proposal, which the government had agreed to in exchange for the party’s support. This paper reviews recent developments in the rental market in Spain and certain misconceptions regarding its evolution. In so doing, it will also draw attention to the scarcity of reliable data available on this issue and the effects that different policies aimed at tackling the rental bubble have had on this market.

Characteristics of Spain’s rental market

During the past 30 years, the incidence of rentals as a fraction of home occupancy in Spain has been very low in comparison with countries with a similar level of development. In the EU-28, where the percentage of rentals in overall home occupancy stood at 30.7%, the percentage of the population paying market price rent stood at 19.8% in 2016. In 2005, the percentage of Spain’s population renting accommodation (including reduced rent and free accommodations) was 19.4%, with 9.5% of the entire population paying rents at market prices. These numbers represent a shift in the size of Spain’s rental market. At the beginning of the 1950s, more than 50% of houses were rented in Spain. The subsequent approval of strict rent controls reduced the supply of rentals, which coupled with house price growth, incentives to support home purchases (tax deductions, the absence of taxation on owner-occupied homes, deductions on real estate capital gains, etc.) fed what some termed a “culture of ownership.” The partial deregulation of rents following the so-called Boyer Act was offset by new incentives for home-buying, so that the percentage of rentals continued to trend lower until nearly the start of the crisis in 2008. It was at this point that analysts began to predict that rental prices would become the next area of focus in the Spanish real estate market (García Montalvo and Garicano, 2009; García Montalvo, 2011) and proposed changes to improve the market’s regulation (FEDEA, 2009).

Since the start of the crisis, demand for rental housing has been on the rise. This shift has been underpinned by more stringent mortgage requirements and the elimination of the tax breaks on home purchases. Other factors that have also contributed to this trend include the prevalence of homeowners struggling to make their monthly mortgage payments, a new awareness of the risks associated with homeownership, and a certain shift in attitude whereby ownership is no longer viewed the only socially acceptable living arrangement. It is also worth noting that the growth in the sharing economy has fed the rise in rental demand, too. While the supply of rental housing has increased, demand has outstripped this growth. This can be attributed to small investors who have snapped up rental housing, attracted by the relatively high yields on rental properties. As a result, the incidence of house rentals is significantly above pre-crisis levels. In 2017, rented living arrangements (other than free accommodations) stood at 16.9%,

[1] which is considerably higher than the percentage observed a decade ago.

The need for reliable statistics about the rental market

The complex adjustment to this new equilibrium, marked by a much higher incidence of rentals than before the crisis, has resulted in a significant mismatch between supply and demand, which has been amplified by political interests. Unfortunately, there is a lack of relevant data and statistics on rentals in Spain. The incidence of rentals can be gleaned from the census or the so-called

Living Conditions Survey. However, neither of these sources is designed to estimate appropriately this percentage. The quality and breadth of statistics on rental prices is even more unsatisfactory following the flawed survey of rental housing of 2006. The survey, carried out by the so called

Observatory of Rental Housing (Observatorio de la Vivienda en Alquiler), and initiative of the Housing Department and the Public Society for Renting (Sociedad Pública de Alquiler),

[2] generated results that were contested by researchers and participants in the market. Thus, those data that are currently available on the rental market generally comes from real estate portals and therefore do not reflect market prices but rather landlords’ ask prices.

Consequently, most analysts and media reports rely on the information provided by the various portals. Unfortunately, the quantity of information gathered on market rents from the portals is often times inversely proportionate to its quality. For that reason, there are significant differences between the ask price provided by the portals and actual market rents.

[3] To make matters worse, the difference between the two is unstable over time, so that the growth rates are similarly not comparable. The gap between landlords’ and tenants’ expectations is evident in the difference between the ask price and the final price.

That fact skews the picture considerably. For example, let us assume a portal advertises one apartment for 5,000 euros a month and another 12 for 500 euros. The average rent is 846 euros. Because the 5,000 euros rent is so much higher, say that apartment and only six of the 500 euros apartments were for rent. What happens to the average rent? According to the portal, it has increased by 35%. What would happen if the six apartments are rented out but the owner looking to rent for 5,000 euros reconsiders and lowers the price to 2,500 euros? According to the portal, the average would have fallen by 7%. The fact that cheaper houses are rented out quickly and more expensive properties take longer to rent skews the figures.

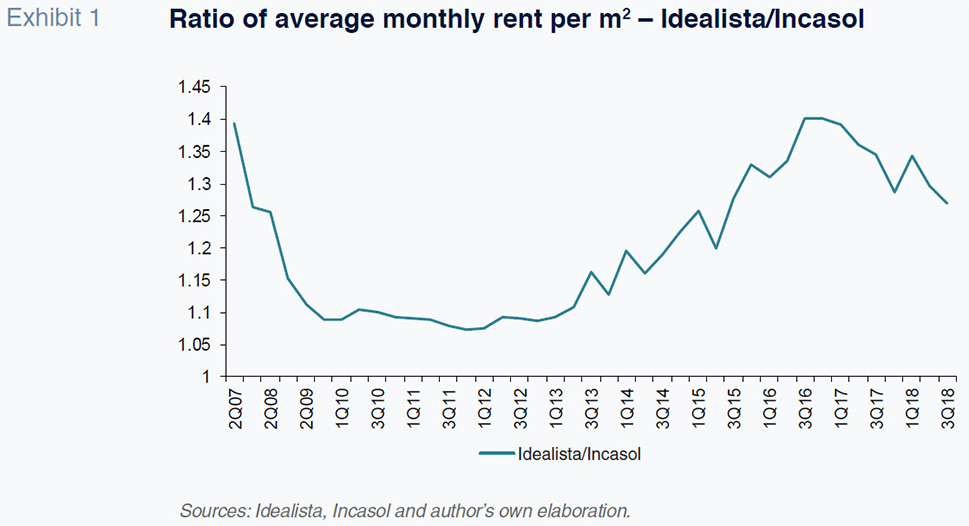

How could one assess the quality of supply-side data? One possibility would be to compare the portals’ data with the rents effectively paid. Regrettably, this is not a realistic exercise. However, in Barcelona the security deposits posted with the official housing market body -INCASOL- make it possible to draw a relationship between ask and market price. Exhibit 1 depicts the ratio of rents in Barcelona according to one of the portals, Idealista, divided by the rents derived from the deposits placed with INCASOL.

Exhibit 1 illustrates how during periods of recession the ratio approaches 1, whereas in times of growth the ratio rises rapidly. That back and forth is logical. An economic expansion is correlated with an increase in demand for rental property, thereby pushing ask prices above market prices. The opposite happens when the economy slows or contracts.

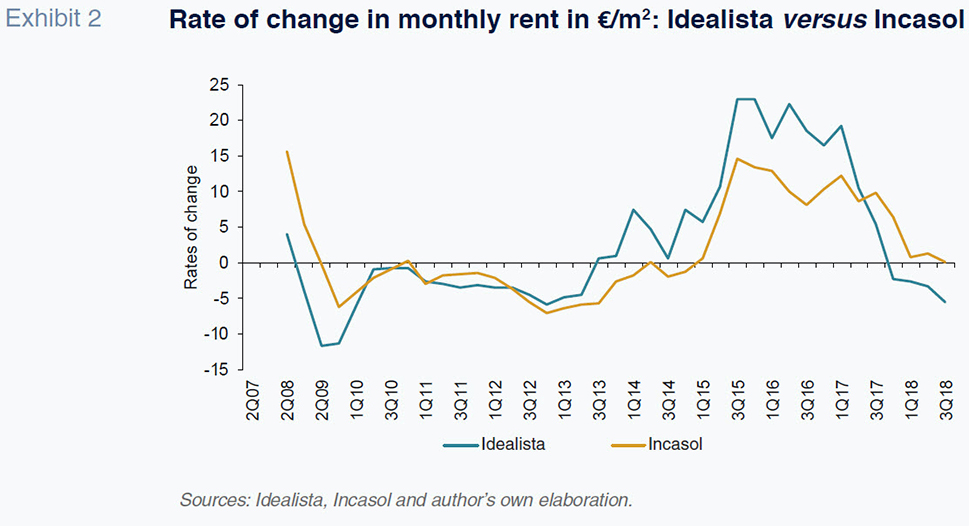

Another way of checking the correlation between real estate portal rents and security deposits is by analysing the growth rates. Exhibit 2 shows how during an economic contraction, the rents published on the real estate portals fall at a faster rate than the market rates, while boom times rents showed higher rates of growth. During periods of stability, such as between 2010 and 2012, the rates of change between these two metrics are similar. It is important to highlight that between the third quarter of 2015 and 2016, the average ask rent increased by 18.5%. However, the prices at which leases were actually signed increased by a narrower 8%. As well, the portal estimated that at the beginning of 2018, there was a reduction in rents of 2.4%, whereas the price at which rents closed increased by 4.4%.

The rental figures for the city of Barcelona show that the portals’ numbers are not a good indicator of real market rents. The fact that the relationship between the two indicators is not proportionate,

i.e., the ratio changes over time, means that the portals’ listed rents should not be used by the rental market. There is urgent need for an official statistical series tracking rents that avoids the pitfalls of the originally constructed (Ministry of Public Works and Urbanism) housing price index and rental statistics of 2006.

The weakness of rental data and the lack of benchmark statistics mean that the information echoed by the media and certain politicians fails to reflect the real trend in rents. During times of growth, propaganda that rents were rising faster than they really were fuelled the entire process. In early 2019, for example, the media continued to insist that rents were rising uncontrollably in Barcelona even though ask prices had been falling for months. Using the most recent data for the third quarter of 2018, some newspapers claimed that rents in Barcelona were still increasing at 5% year-on-year when the reality was that rents per square metre had stabilised. That growth of 5% relates to total rents and not rent per square metre.

Why are rents rising in big cities?

The fast rise of rental prices in big Spanish cities, particularly Madrid and Barcelona, has spawned the notion of a “rental market bubble”. Indeed, one of the clearest indicators of the bubble in house prices in the past, in addition to the astounding growth in credit, was actually the low yields on rentals. That yield bottomed at 2%. Why would anyone want to pay an astronomical price for housing when it was offering such a low return in comparison with other assets? The only explanation is that the expectation was that prices would continue their ascent and buyers would realise capital gains. Ultimately, it was such unrealistic expectations about the outlook for prices, together with abundant credit, that fed bubbles. Today, with rental yields between 5% and 7%, house prices are determined by the rents they can secure. Lastly, while house prices can rise unfettered so long as the availability of credit continues to increase, the same cannot be said of rent, which is capped by household income.

The rapid rise of rents in certain major cities has triggered an examination of its causes. Here, it is important to avoid raising concerns supported by a biased selection of housing affordability indicators. The latest EU estimates from 2016 indicate that the severe housing deprivation rate in Spain (1.7%) is well below the EU-28 average (4.8%), the Eurozone average (3.5%) and even below that of countries, such as Sweden, France or Germany. Secondly, the housing affordability ratio (the percentage of households that spend more than 40% of their equivalised disposable income on housing) stood at 10.2% in Spain, which is again below the EU-28 (11.1%) and Eurozone (11%) averages. Owner occupied housing in Spain has very low levels of housing deprivation. Looking at the segments of the population living on reduced rent or in free accommodations (10.6%), Spain continues to compare favourably with the EU-28 (13%) and the Eurozone (11.8%). The affordability issue is concentrated exclusively in the market rent segment (a very small percentage of the housing market), where this ratio is 43% in Spain, which is significantly above the EU-28 average (28%).

Without a doubt, the increase in the percentage of disposable income spent on rent in the market price rental sector has created enormous housing access issues. This has been compounded by the rise of temporary work contracts and low salaries in Spain, which makes getting a mortgage more difficult. There are two main problems in tackling this situation. Firstly, the almost complete absence of accurate information about the fundamental market variables prevents rigorous analysis of the root causes. Secondly, because it is so hard to obtain empirical results, the recommendations for tackling the problem are based on ideological “hypotheticals” and proposals for measures that have previously failed.

The first alleged culprits are the large-scale investor landlords. However, contrary to popular misconceptions, the supply of homes for rent remains dominated by small, local property owners (small investors, pensioners, etc.). Over 2.3 million Spaniards declare property tax receipts on their tax returns. Large-scale investors represent less than 5% of the market. It is hard to conceive that these landlords could be exercising monopoly power, controlling prices and pushing them higher at their discretion. When debating measures for protecting tenants, it is important to recall that on the other side of the contractual relationship there could be a pensioner or small saver who rents out his property to top up his income.

The second alleged culprit is the home sharing arrangements, or holiday apartments. There was a lot of controversy around the impact of home sharing in the summer of 2018 when the anti-trust authority, the CNMC, engaged in a debate with Madrid’s municipal government. The CNMC published a report which indicated that there was no evidence that home sharing was having an impact on rents. It is too simplistic to assume that all holiday apartments would be on the long-term rental market if, for example, platforms like Airbnb were banned. Many of the apartments for rent on those platforms are available to rent for very short periods of time, which tend to coincide with periods when their primary occupants are away. Others might not be put on the market because their owners might think that standard rents are insufficient to compensate them for the risk of renting out their properties. What’s more, the present conditions may have played a key role in the decision to buy and then subsequently rent out those properties. Therefore, the impact of home sharing depends on the relative size of the sector and its impact on the supply of rental homes. That effect can only be analysed using empirical evidence, not theoretical arguments.

The most simplistic approach is to interpret the coincidence between the start of the home sharing boom and the increase in rents. However, it requires putting aside the fact that this coincides with economic growth and a fall in unemployment. There are also other ad hoc factors such as the 20% contraction of rentals in Barcelona between 2008 and 2013. In sum, that coincidence is anything but credible evidence. Moreover, in Barcelona the number of leases registered with INCASOL increased by 23% between 2015 and 2017. Even more significant is the doubling of the number of leases since the start of the crisis.

The empirical evidence suggests that there is no correlation on a district-level between the number or proportion of holiday apartments in Barcelona and the increase in rents. Obviously, that evidence is weak as it is not based on credible causal analysis but it does make it hard to justify claims that home sharing is having a significant impact on conventional rents. So, how did Madrid’s municipal authorities justify their claim that the proliferation of apartments for use by tourists had led to an “astronomical” increase in rents? The crux of the argument is based on an interpretation of a report by members of a neighbourhood association. The authors attempt to be more quantitative, indicating that the “the statistical evidence about the movement in prices in the Central District with respect to the rest of the city appears to endorse, at least partially, this hypothesis.” But the report does not provide evidence that rents in the Central District have deviated from the average trend for all of Madrid, given that there are other districts where rents have gone up more sharply. In short, districts that have seen that highest increase in holiday apartments are not where rents have gone up the most. The report concludes with the authors noting that they had “encountered significant limitations due to the absence of sufficient data series, making it hard to establish robust and conclusive models.” Despite adding that there are many other factors that affect rental prices, the report ends by claiming that there is a correlation between home sharing and rental prices.

Given the challenge of finding empirical evidence in Spain, we need to look at what has happened in cities in other countries. Such an exercise is always complicated because extrapolating data from one city and applying it to another implies making a number of assumptions. Due to the novelty of the home sharing phenomenon, there are few published studies. The only one that can be described as in any way rigorous examines the issue in Boston. (Han and Merante, 2017). The authors concluded that a standard deviation increase in Airbnb listings would imply a 0.4% increase in ask rents, when rents in the city of Boston are growing at over 5%. That increase is barely statistically significant. The study, which also complains about the lack of good data, relied on ask rents rather than market rents, which partially undermines its credibility.

In short, the CNMC is right to state there is no evidence of a correlation between home sharing and rents. This is not to say there is not a correlation but that there is not enough information for a reliable study to determine whether such a correlation exists.

Another factor coincides with the arrival of Airbnb in 2014, namely the start of the economic recovery. The city of Barcelona has benefitted significantly from the effects of the economic recovery. Taxable income per tax-payer in Barcelona was higher by 2015 than in 2008 and by June 2017 there were fewer registered job-seekers in Barcelona than in December 2008. Between the start of the recovery and 2017 (estimate based on latest figures available) Barcelona’s GDP increased by 12.6% in constant prices. Similarly, between the end of 2013 and the end of 2016, GDP per capita increased by 8.5%. But what has happened in terms of income distribution? Whereas in 2008 wages and salaries plus social security accounted for 75% of all income, by 2014 (last year for which these figures are available) they represented 81% due to the lower weight of benefits. That economic recovery must explain at least some of the rental market’s rebound.

The third culprit may relate to demographics. In the case of Barcelona, the population has remained constant for the last six years while the average household size has increased somewhat, implying fewer households. Moreover, the number of young people at the age of leaving home, supposedly the biggest source of demand, has fallen. It is true that foreigners from wealthier countries have increased in number since 2014 and the Latin American community has shrunk but the impact on per capita income is insignificant with respect to the rental market in Barcelona (assuming they rent and do not buy).

Finally, another explanation is the scarcity of rental housing supply and the market’s attendant inability to adjust without major swings in rentals.

Recent policy proposals

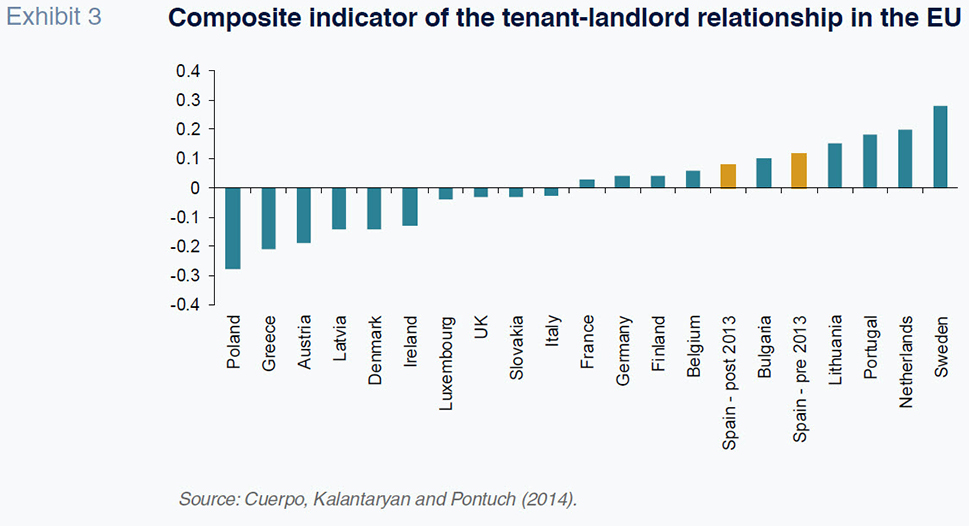

In theory, there are plenty of public policies that could influence the dynamics of Spain’s housing market. The question is deciding when to apply them, which are most effective and which cause the least collateral damage. The Royal Decree-Law (RDL) on urgent measures in housing and rentals has placed public policy on rentals back in focus. Any legislative changes introduced alter the delicate balance between landlords and tenants and therefore must be studied and formulated with care in order to avoid creating new adverse effects in the market. The first question relates to the current state of that balance in Spain. The country offers tenants reasonable levels of protection as referenced by OECD and EU indicators. Exhibit 3 provides the composite indicator of the relationship between tenants and landlords for the EU member states. Lower values of the composite indicator reflect lower degrees of tenant protection. The exhibit shows that Spain is well positioned in terms of tenant protection, even after the reforms of 2013.

The changes in the RDL include extending lease terms from three to five years and capping security deposits at two months’ rent, except for long-term leases and leases arranged by large landlords, which are set to a minimum of seven years. Lengthening the term of lease agreements is reasonable considering the fact that renting is an increasingly more popular option, although it is unclear why large landords should be subject to a different regime. That measure gives tenants greater stability. In addition, the adjustment of rents throughout the life of the contract will be limited by CPI inflation.

Nevertheless, it will not necessarily effect the growth of rents if the price trend proves protracted. If rents continue to increase, the price for accommodations will simply reset to market prices, triggering an accumulated five-year rise in prices instead of a three-year increase. Moreover, leases have tended to have terms of over three years. Their duration has averaged 4.5 years. It is also worth noting that the minimum lease term only applies to the landlord and not the tenant, giving the latter an advantage that is not usually considered. When rents fall, as was the case in Barcelona between 2008 and 2013 (-20%), tenants can unilaterally break or threaten to break their leases to their advantage. That phenomenon was widespread in Barcelona during the initial stage of the financial crisis and forced landlords to drop their rents.

The RDL also capped the size of the security deposit paid to landlords at two months’ rent. It seems reasonable not to let landlords ask for five or six month rent as security, however, capping that deposit could still push more vulnerable tenants out of the market if the cap is not accompanied by other measures. For example, a public subsidy could be set up to pay for insurance against default by tenants affected by this cap.

The most controversial aspect of the public debate surrounds the introduction of rent controls. Although the RDL did not contemplate this potential policy, it did appear in the agreement struck between the Socialist (PSOE) administration and Podemos. It has been long established by empirical evidence that this policy is ineffective. Regrettably, this erroneous approach, which involves the introduction of price controls in the rental market, attracts significant support. A good example of this is hyperinflation in Venezuela, which started with measures aimed at controlling prices in response to accusations that merchants were escalating prices. Those price controls distorted markets and had no effect on inflation, that at the end of 2018 rose to 1,000,000%, a record high. This occurred because policymakers failed to adequately examine the situation as well as the long-term direct and indirect consequences of price controls. In Venezuela, the central bank is rapidly printing money, causing prices to skyrocket. This means price controls will have no effect so long as the authorities persist with this policy.

Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman has referred to rent controls as “among the best-understood issues in all of economics, and—among economists, anyway—one of the least controversial”. Consequently, the tendency to paint the issue as one that is still under debate among economists is patently false. There is an abundance of empirical evidence about first-generation rent controls (those that limit rents in absolute terms, rent caps or ceilings). The studies point to a reduction in the supply of rental homes, an adverse impact on mobility and a suboptimal allocation of resources that benefits some tenants and damages others. A recent study by Diamond, McQuade and Qian (2018) shows that rent controls in San Francisco prompted many owners of rental units to sell them, driving a significant contraction in rental housing supply. This reaction generated more inequality as the buyers of the houses that exited rental market were high-income households. There is not enough evidence to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of the so-called second generation rent controls, which limit the growth in rents rather than their absolute levels (rental brakes or rent stabilisation). However, informal observations indicate a minor impact on rental price growth alongside evidence of black-market payments to circumvent the controls and reduction in the supply of rental units. In addition, these controls have disincentivized building maintenance. Berlin is frequently referenced in debates about rent controls but less often discussed is their negative impact in that city. Also, while these policies may have been well-intentioned, it is important to keep in mind that any success occurred in a different institutional and real estate context. Could rent policies possibly have the same impact in a city where 70% of houses are for rent as in a city where just over 25% are for rent?

The adjustment of supply and demand in the Spanish rental market might have been smoother if a significant amount of public housing was available for rent. Unfortunately, policymakers have focused on providing subsidies for lower income households to assist in home ownership ambitions instead of lowering their rental costs. This may have been effective for winning votes, but it had the deleterious impact of redirecting resources that could have been used to increase the stock of social housing available for rent. Looking at the houses built between 1980 and 2008, that stock would now exceed 2 million units. The crisis offered opportunities for municipal and regional authorities to quickly and cheaply increase their stock of social housing for rent. The bargain prices at which the banks were selling foreclosed housing made this the ideal source of new social housing. Instead of taking advantage of the opportunity, governments chose to building new public housing without restricting its use to social rents. Then, when the pace of production fell short of forecasts, they resorted to controversial measures, such as the obligation imposed by the Barcelona municipal government on private developers to earmark 30% of the houses they build to social housing. That measure is bound to have a limited effect (around 300 units per annum) and serves to heighten the sector’s legal uncertainty.

A situation has therefore developed where strong demand has been met by an inadequate supply response. Given that it is very hard to influence demand for rentals, at least not without fuelling a fresh bout of irresponsible mortgage lending, any measures that trigger a contraction in supply without clear and proven benefits should be avoided. This makes it all the harder to justify government decisions that undermine legal certainty, such as allowing or encouraging squatters or considering the application of retroactive criteria. Legal uncertainty drives landlords to look for higher returns to compensate for the greater risk they are assuming and could prompt many to sell their properties, further restricting the supply of rental housing. Moreover, the increase in financial market volatility over the past year means the housing market now looks like a safe haven for investors. This has helped keep prices afloat and made landlords far more sensitive to the risks implicit in renting, given the clear-cut returns on sales.

Conclusion

After 40 years of erratic housing policy, it is important to acknowledge that the current issues surrounding the Spanish rental market will not be easily resolved. The incorporation of basic economic principles and a shared commitment to address these issues could prevent them from reappearing in the future. Regional and municipal authorities should also promote the mobilisation of public land through public-private initiatives and speed up the planning approval process. Most important of all, public policy must incentivise the supply of rental units, not discourage it, when there is a shortage of rental accommodation.

Notes

That percentage refers to rents at market prices and at below market prices but does not include other arrangements, such as free accommodations.

The Observatory and the Public Society was dismantled in the following years and the name of the Department of Housing has since changed.

Reports by Tecnocasa show that the discount associated with ask prices is highly pro-cyclical.

References

CUERPO, C., KALANTARYAN, S. and PONTUCH, P. (2014). Rental market regulation in the European Union. Economic Papers 515. European Commission.

DIAMOND, R., MCQUADE, T. and QIAN, F. (2018). The effect of rent control expansion on tenants, landlords, and inequality: evidence from San Francisco. Working paper. Stanford Business School.

FEDEA (2009). Por un mercado de la vivienda que funcione: una propuesta de reforma estructural [For a housing market that works: a proposal for structural reforms].

GARCÍA-MONTALVO, J. (2012). El alquiler y la solución al círculo vicioso de la viviendas [Rent and the solution to the vicious housing circle]. ARA, March 18th.

GARCÍA-MONTALVO, J. and GARICANO, L. (2009). El alquiler como solución [Rent as the solution]. La Vanguardia, October 18th.

HORN, H. and MERANTE, M. (2017). Is home sharing driving up rents? Evidence from Airbnb in Boston. Journal of Housing Economics, 38, pp. 14-24.

MINISTRY OF DEVELOPMENT (2017). Observatorio de vivienda y suelo. Boletín especial: alquiler residencial [Housing and land observatory. special bulletin. house rentals].

José García Montalvo. Professor of Economics at Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Research Professor (Barcelona GSE and IVIE)