Spanish exports: Weak performance in 2018

For the first time since the financial crisis, Spain’s export performance has trended below international growth rates. The contraction in 2018 was observed broadly across sectors and markets, suggesting it unlikely that traditional explanatory variables alone could account for this weak performance.

Abstract: The global economy performed unevenly in 2018, with a notable slowdown in Europe and an uptick in US growth thanks, in part, to the Trump administration’s tax cuts. Drilling down further, global trade growth expanded by just 3.3% last year, falling from 4.7% in 2017. However, the picture is somewhat worse for Spain, where the slowdown was more intense. Particularly noteworthy is the reduction in demand from the UK, which began in 2017 and failed to recover in 2018. From a sectoral performance, the automotive industry performed weakest with a 1.5% contraction in current prices. That said, the broad nature of the slowdown in Spain’s external sector suggests that traditional factors relating to a specific export market, sector, unit labour costs or exchange rate movements alone cannot account for this downward trend. It therefore remains to be seen whether the recent figures point to a one-off event, or the start of a more prolonged period of weakness in Spain’s export performance.

International backdrop

The European economy slowed considerably in 2018, with the contraction more pronounced during the latter half of the year. This was largely due to new emission tests and standards that temporarily paralysed the automotive industry. The slowdown in China also played a significant part, taking a toll on the German economy, which nearly entered a technical recession. Italian GDP contracted for two quarters in a row amidst the ongoing conflict between the Italian government and the European Commission over the former’s deficit target, while the French economy’s performance was undermined by the gilets jaunes disturbances.

Outside of Europe, the picture was mixed. In contrast with the EU, growth in the US accelerated, fuelled by the Trump administration’s tax cuts. China registered its lowest level of growth since 1990. Otherwise, the IMF’s January estimates show that emerging economies expanded close to 2017 levels, thanks to greater momentum in other emerging countries, such as India.

The trade war unleashed by the US was undoubtedly the most significant development on the international front in 2018. The decision to impose tariffs on several products had the biggest impact on Chinese exports, although in some cases it also hit European producers (as in the steel sector). These moves, exacerbated by the threat of more tariff hikes on other vulnerable products, such as European-made cars and nearly everything ‘made in China’, were followed by retaliation on the part of the EU and China.

The uncertainty regarding the new trade regime that will emerge from talks finally underway between the US and the EU on the one hand, and the US and China on the other, and their impact on the global value chains, may have had an adverse effect on international investment decisions. This was further compounded by ongoing Brexit negotiations. The spectre of a ‘no deal’ Brexit and the failure to define the model that will govern future trade relations between the UK and the EU may also help explain the slump in the European economy during the second half of 2018. In the UK, these developments have been a significant factor in the downtrend in capital goods investment since 2016.

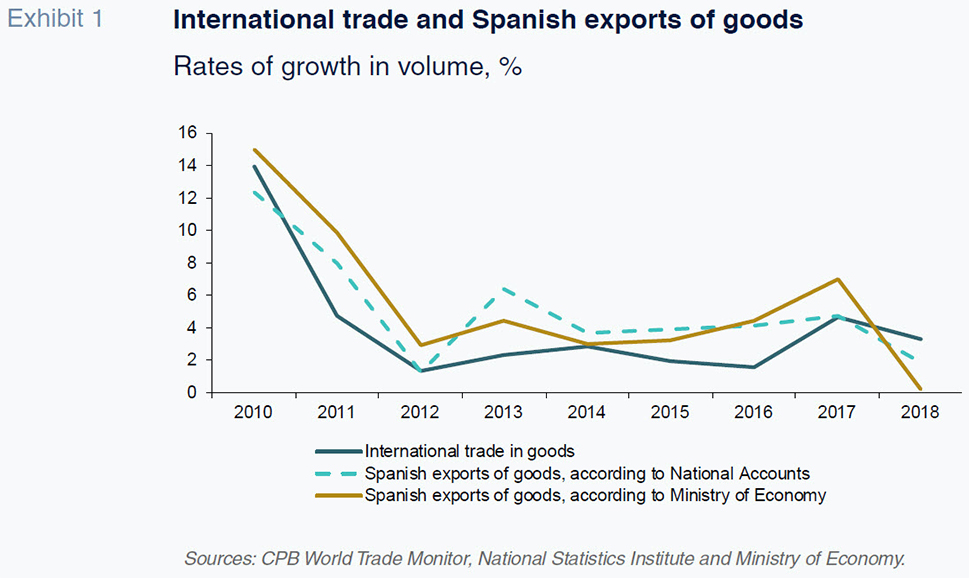

Against this backdrop, growth in global trade slowed in 2018, from 4.7% to 3.3%, according to the CPB World Trade Monitor. Particularly notable is the slowdown in global trade observed in the fourth quarter. Nevertheless, the annual rate of global trade growth continues to remain above the average

since 2011.

Spanish exports in 2018

Spanish exports of goods and services experienced a dramatic slowdown in growth last year. According to the provisional national accounting figures, growth in goods exports eased in real terms from 4.7% in 2017 to 1.8% in 2018. However, the Ministry of the Economy

[1] estimates that the slowdown was far more pronounced, with export growth dropping from 7% in 2017 to 0.2% in 2018. Either way, the slowdown was more intense than the trend observed in global trade and marked the first clear-cut underperformance with respect to the global export growth for the first time since the start of the crisis (Exhibit 1).

The performance was worse than calculated by traditional models for estimating the export demand function.

[2] These models rely on explanatory variables, such as demand in export markets, domestic demand and certain measures of competitiveness including the nominal effective exchange rate or the real effective exchange rate based on unit labour costs (ULCs). Consequently, some of the slowdown could be attributed to reduced growth in export markets, the strength of domestic demand, the euro’s appreciation, or the slight loss of competitiveness in terms of ULCs. However, these factors alone are an insufficient explanation of Spain’s weak export performance in 2018.

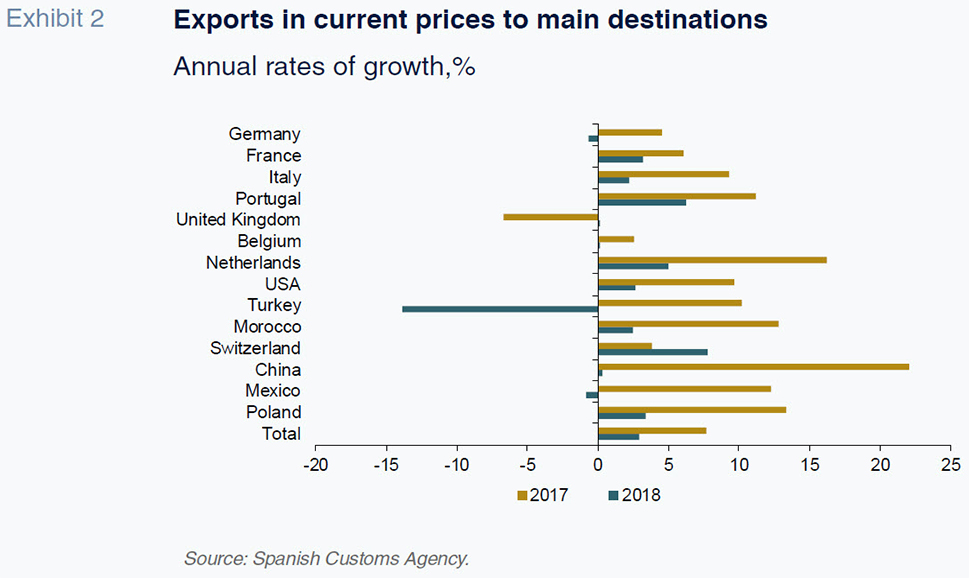

Trend in exports by destination market The slowdown in exports of goods was widespread across markets and economic sectors. A slowdown in the pace of purchasing of Spanish goods was observed in nearly all the important export destinations in both Europe and the rest of the world (Exhibit 2). Turkey saw a particularly pronounced reduction in demand for Spanish goods. The country, hit by a currency crisis that led to the depreciation of the lira against the euro by nearly 40%, purchased 13.9% fewer goods from Spain in current prices. Exports to China also slumped: having registered growth of 22% in 2017, they stagnated in 2018. The countries that saw the greatest uptick in demand for Spanish exports in 2018 were Portugal and France. That said, in both instances their purchases increased by less than in 2017.

In the UK, which is the fifth largest market for Spanish exports, growth was virtually nil in 2018, following a contraction of 6.7% in 2017. That contraction was the only one recorded among the major export markets in 2017 and was the result of the depreciation of the sterling, the slowdown in consumption and the drop in capital goods investment suffered by that country as a result of the uncertainty triggered by Brexit.

As a result, sales of capital goods to the UK fell hard in 2017. But the automotive sector fared the worst, slumping by 21%, so that the capital goods sector actually overtook the automotive sector in terms of Spanish exports. The downtrend in both sectors continued in 2018 but was offset by an improvement in others, including oil derivatives, medicines, iron, steel and certain chemical products.

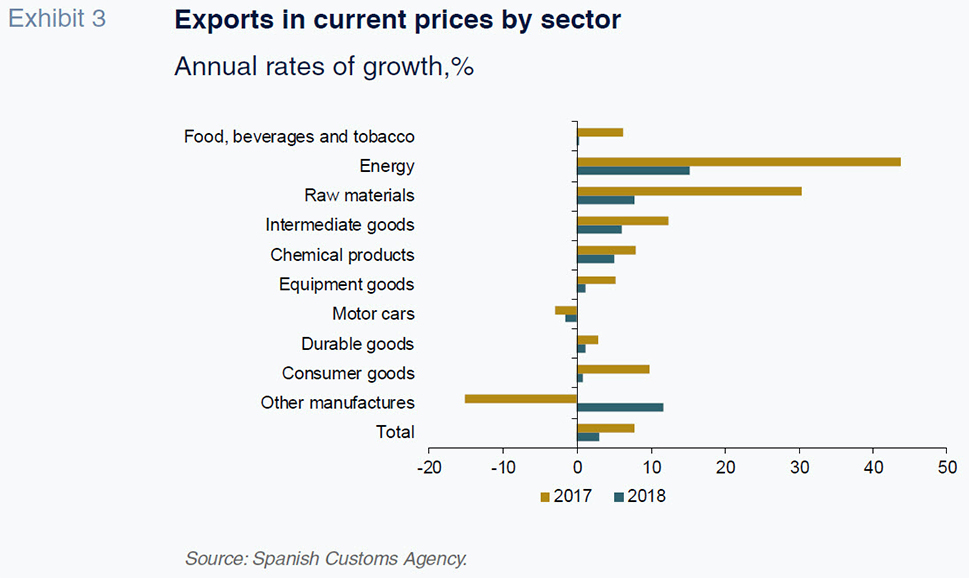

Trend in exports by sector Virtually all sector categories saw their exports slow in 2018 (Exhibit 3). Energy products (mainly oil derivatives) was the best-performing category, despite registering lower growth than in 2017. The automotive sector (cars, motorbikes and parts) was the worst-performing sector with exports contracting by 1.5% in current prices. Looking at the sub-segment comprised of just cars and motorbikes, the decline was even sharper at 4.1%, extending the significant contraction of 5.5% previously registered in 2017. The slowdown in manufactured consumer goods, specifically textile goods, which account for 10% of Spanish exports, was also noteworthy.

The primary market for exports of Spanish cars and motorbikes (excluding parts) is Germany, which consumes around 20% of these goods, followed by France at 19%, and Italy and the UK, both with shares of around 10.5%. In total, eight countries (those listed above plus Belgium, Turkey, Portugal and Austria) account for 75% of Spanish exports in this sector. Although the UK market accounted for nearly half of the decline in total sales, the downturn was widespread, marked by negative figures in six of the above-mentioned export markets. Most of the major destination markets also contracted in 2018. After the UK, Turkey had the largest adverse impact on export growth in 2018. Note that this trend contrasts with the expansion of automotive exports from the EU as a whole, which registered growth in both 2017 and 2018 (the latter based on provisional data to November).

Conclusions

For the first time since the start of the crisis, exports of Spanish goods clearly underperformed in terms of international trade growth. However, the slowdown in Spain’s main export markets, exchange rate movements, the trend in cost competitiveness and strong domestic demand do not fully explain the weak performance in 2018.

Similarly, the underwhelming performance of a specific sector or market cannot account for the broad-based slowdown. The UK was one of the worst-performing markets, with Spanish exports unable to recover from the sharp fall suffered in 2017 on the back of the uncertainty sparked by Brexit. The worst-performing sector was the automotive sector, which also contracted in 2017. Still, growth was weaker in nearly every sector category.

It is too soon to tell whether Spain’s poor export performance in 2018 will prove a one-off event or is the start of a protracted slowdown. The weakness of the automotive sector over the last two years is particularly worrisome. However, it should be noted that the sector has been affected by a series of ad hoc circumstances and that both export and production volumes registered growth that was considerably above the EU average in prior years. Given its importance to Spain’s productive and export performance, it will be important to monitor the ongoing export trends in the automotive industry, particularly in light of the far-reaching transformation in which it is immersed.

Notes

Customs figures deflated using the unit value indices compiled by the Ministry of the Economy.

Several models have been used to estimate real exports of goods for both the figures in national accounting terms and for those calculated by the Ministry of the Economy, using annual data for the period since the start of the crisis in order to capture possible structural changes with respect to the prior period. The models, which include a mechanism that corrects for error, introduce different measures of the lagged exchange rate or, alternatively, the real effective exchange rate based on ULCs, growth in imports in the main export markets and lagged growth in domestic demand as explanatory variables. In every instance, the results reveal that the growth in exports in 2018 was lower than predicted based on the explanatory factors, with errors that were above the average for the period, albeit within the confidence intervals.

María Jesús Fernández. Economic Perspectives and International Economy Division, Funcas