Spanish economic policy in response to Covid-19

The health crisis unleashed by the Covid-19 pandemic is one of the greatest challenges facing the global economy since the Great Depression, prompting a contraction of Spanish GDP this year of an estimated 3.0%. The speed and timing of the recovery will depend in part on the duration of the pandemic, as well as on the scale and efficacy of domestic and EU stimulus measures.

Abstract: The Covid-19 health crisis poses a major challenge for economic policy due to the unprecedented nature of the shock and because the repercussions will be significant. GDP is expected to drop sharply in the first half of the year, followed by a rebound in the second half, resulting in a contraction for the whole of 2020 of an estimated 3% – etching out a U-shaped recovery. Compared to other more alarmist predictions, that scenario is already playing out in countries hit by the virus earlier, such as China and South Korea. In 2021, the Spanish economy could grow by 2.8%. The emergency measures announced to date by the Spanish government and the ECB in response to the situation are a necessary first step; however, the authorities will have to continue to fine-tune the intensity of their stimuli depending on the duration of the crisis with the aim of safeguarding productive structures, preserving jobs at sustainable businesses and ensuring that the rebound materialises as anticipated.

Introduction

The health crisis unleashed by the Covid-19 pandemic is one of the greatest challenges facing the global economy since the Great Depression. The crisis has no precedent in recent history insofar as it combines a supply shock – a hit to productive capacity –with a demand shock– a sharp slump in international and home-market demand, coupled with tight restrictions on the movement on people (with ripple effects on both supply and demand). Moreover, in contrast to previous recessionary episodes, this one stems from circumstances unrelated to the economy and its severity will depend in part on factors that are not within human control, such as the seasonality of the virus, its ability to mutate, and its global reach.

The purpose of this article is to identify the key challenges for economic policy that arise from Covid-19. It is important to underline the many constraints on this exercise, due to the exceptional nature of the crisis, the announcement of sizeable monetary and fiscal stimulus measures and the uncertainty prevailing internationally. The analysis is based on the assumption that the health crisis will be limited in time, so that the confinement measures can start to be relaxed before the Summer in Spain, as well as the rest of Europe and the US. It assumes, therefore, that the biggest impact will be concentrated in April and May, gradually easing in the ensuing months, with activity beginning to normalize during the third quarter.

That assumption is underpinned by the precedents in China and South Korea, which have managed to flatten the coronavirus expansion curve, facilitating a recovery in productive activity. Moreover, the estimates take into account the measures recently announced by the Spanish government in the context of the state of emergency

[1] and by the ECB.

[2]

Nevertheless, the lack of comparable historical precedent, coupled with prevailing uncertainty regarding the duration of the crisis and the extent to which it will spread internationally, makes it hard to analyse the public policy response. The contents of this paper, therefore, should be viewed as preliminary and subject to update as the pandemic unfolds.

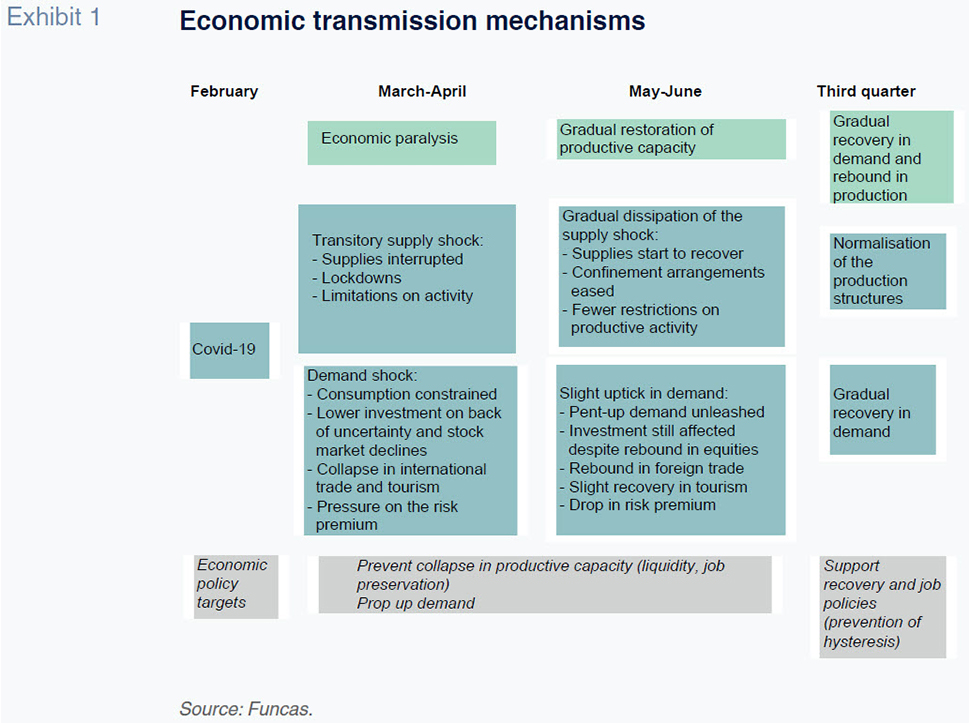

Coronavirus and the Spanish economy: Transmission mechanisms

From the economic standpoint, the virus, coupled with the measures taken in efforts to try and contain it, are equivalent to a supply shock with a drastic albeit transitory impact on productive capacity. That shock translates into a reduction in the inputs needed for manufacturing, with a particularly significant impact on the sectors more dependent on global supply chains. Other factors shutting down activity are the lockdown of most of the available workforce, who cannot work remotely or travel, and the closure order affecting commercial establishments other than those selling food, essential goods and pharmaceutical or health products.

These supply-side effects would directly affect –at varying degrees– the manufacturing, construction, retail, hospitality, leisure and culture sectors, amounting to around 14% of GDP (under conservative assumptions).

The virus will also undermine demand. Firstly, because one of the key transmission channels of this health crisis will be consumption, which will slump sharply in March and April. To estimate the scale, we made assumptions about the potential trend in the 12 groups of goods and services into which the Household Budget Survey classifies expenditure, factoring in their relative weights in total household expenditure. We also assumed a recovery in pent-up consumption in certain groups of goods over the following months, and, subsequently, a return to more stable spending patterns, albeit below pre-crisis levels.

Framed by all of these assumptions, consumer spending would contract sharply in the first and second quarters, and recover in the rest of the year progressively, so as to reach the moderate pace of growth observed prior to the crisis.

Investment is the second transmission channel, due mainly to decision-making paralysis: investments will be postponed or cancelled altogether, as uncertainty could take some time to dissipate even after the virus is under control.

Exports are set to fall sharply as a result of the spread of the virus across Europe and the US. To estimate by how much, we start from our predictions for a contraction of eurozone GDP of 4% in 2020 and growth of 2% in 2021.

These assumptions are less pessimistic than those of certain prestigious research houses such as Morgan Stanley (-5% in 2020), Capital Economics (-6%) or JP Morgan (-11.4%).

[3] We also looked at the drop in activity in China and South Korea as references.

The impact on exports of tourism services is expected to be particularly dramatic, this being the demand component estimated to erode GDP the most. The return to normality is likely to be much slower in this sector, which probably will not reach pre-pandemic levels until next year. The collapse in tourism will detract sharply from GDP growth via its impact on the external sector, with the drop in imports as a result of the contraction in domestic demand not expected to be a sufficiently mitigating factor.

One of the biggest sources of uncertainty lies with the severity the lockdown measures will reach in both the European countries not as badly affected to date and in the US. If measures as disruptive as those taken in countries such as Spain and Italy were to become widespread, the impact on exports would be even greater than contemplated in the present projections.

In short, more than forecasts, the numbers presented here should be seen as a simulation of the impact Covid-19 would have on the Spanish economy under the above-detailed assumptions and scenarios.

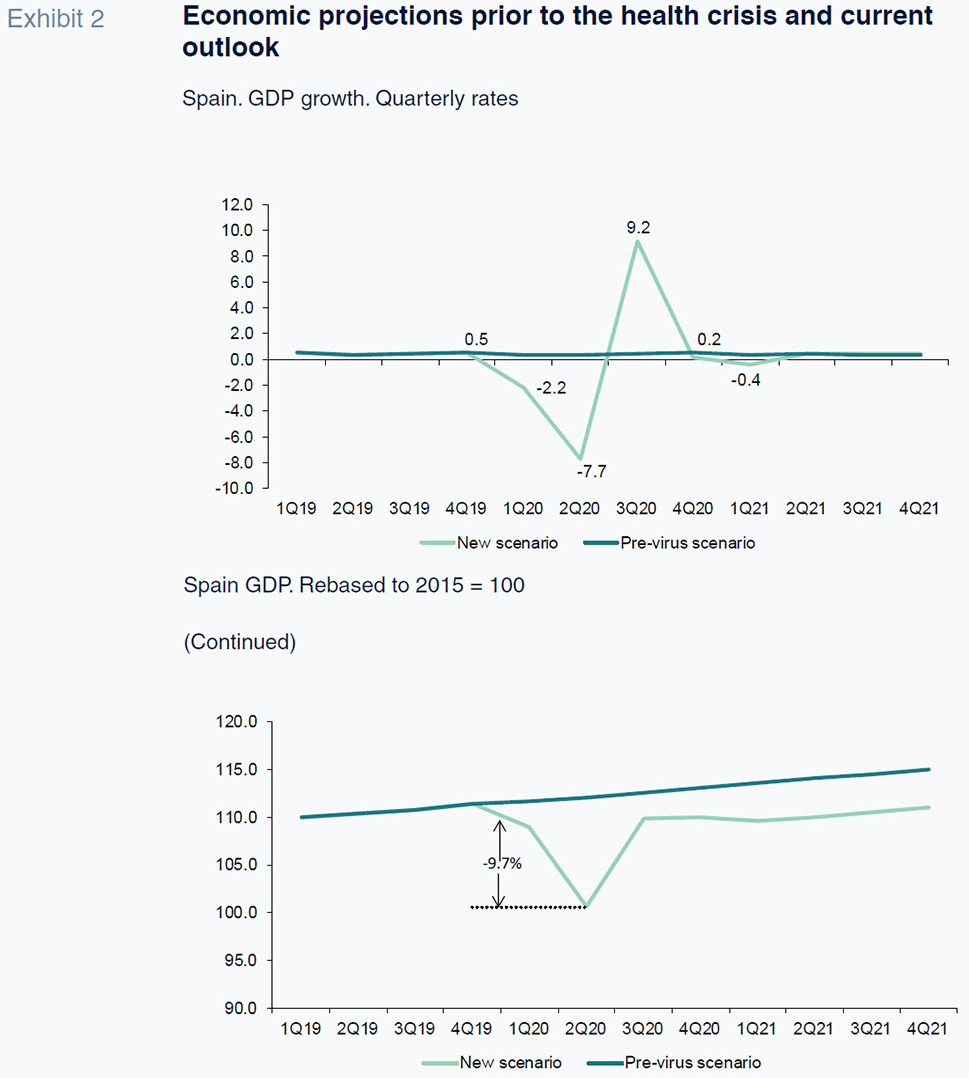

The outcome would be a contraction in GDP of close to 10% in the first half of the year, followed by a rebound during the second half, as productive activity gets back on its feet and demand begins to recover, although without reaching pre-crisis levels (Exhibit 2). GDP would contract by 3% in 2020 taken as a whole. The anticipated recovery during the second half of the year of much of the activity foregone would drive growth of 2.8% in 2021. The idea is that the economic trend would be close to U-shaped (and not V-shaped because in some sectors, notably tourism, the return to normality would be relatively slow). [4] As already mentioned, these estimates are less alarmists than some of the most recent predictions. The difference might reflect our assumption that the Spanish economy would broadly follow the patterns registered in the countries hit earlier by the virus, such as China and South Korea.

In general, and despite the economic rebound anticipated in the second half of the year, it will be some time before we see normalisation in the trend in household savings, which are initially bound to rise sharply due to the confinement measures and later trend lower in keeping with the recovery. Corporate investment decisions will similarly take some time to settle. As a result, we estimate that the pre-crisis GDP level would not be revisited until mid-2022.

The impact on employment is expected to be severe but, to some extent, largely limited in time. Most of the jobs lost would be regenerated during the second half of the year, with the sectors affected by the supply shock and those related with tourism expected to suffer longer-term consequences.

The role of economic policy

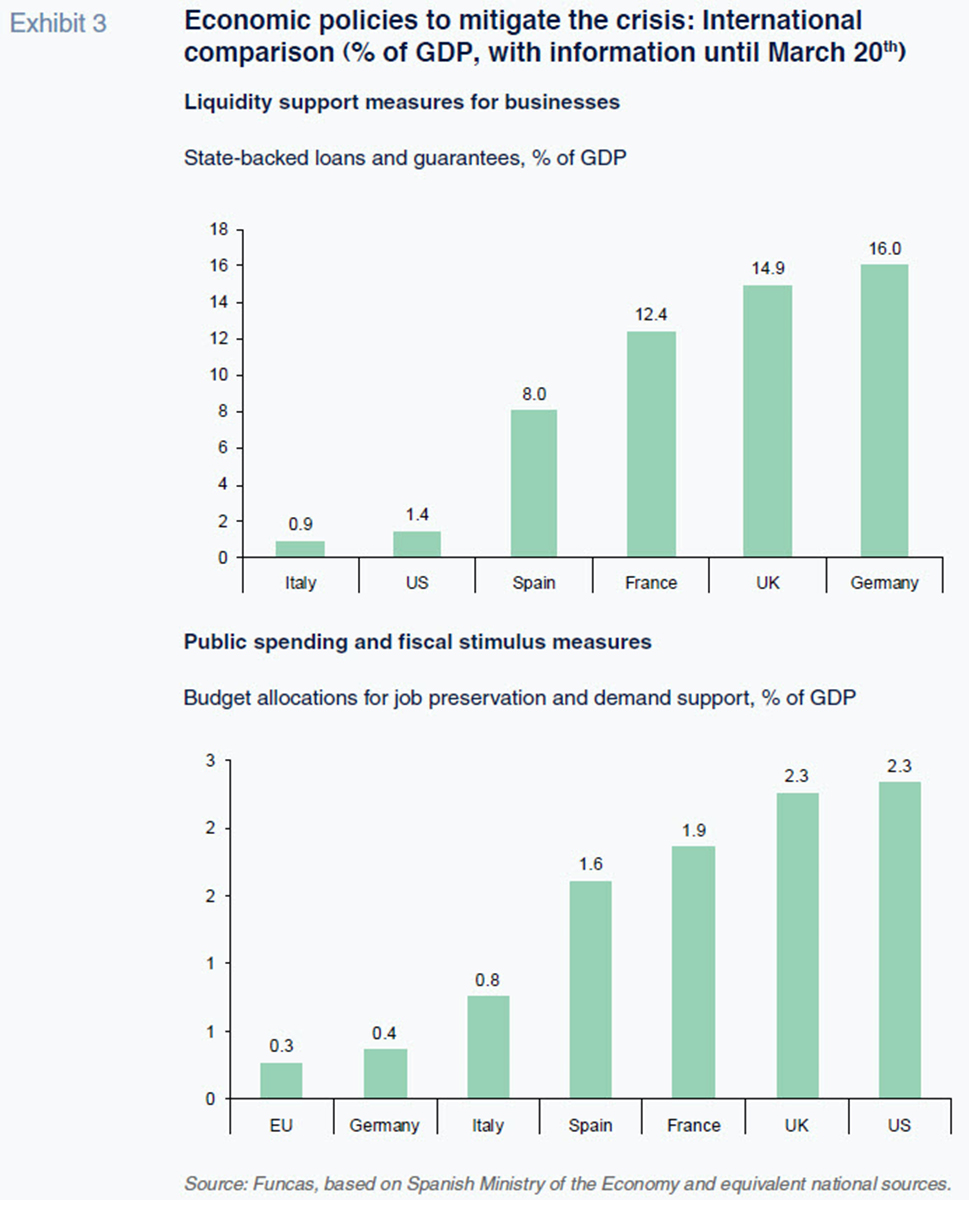

The recovery expected from the second half of the year relies on the assumption that the economic policy response will rise to the occasion (in addition to the assumption that the health crisis would last for a relatively limited period of time). The policy response modelled assumes, firstly, measures designed to prevent the closure of businesses: loans on favourable terms with government collateral, and state guarantees to facilitate the payment of invoices and taxes. The scale of the measures contained in the emergency decree amounts to 100 billion euros, close to 8% of GDP, a level that could be doubled depending on the bank lending triggered by the loan guarantees. That volume is somewhat lower than in neighbouring countries such as Germany but higher than currently planned in Italy (Exhibit 3).

Secondly, the strategy includes measures which, unlike the public loan guarantees, entail government spending or a reduction in tax revenue. They include measures designed to preserve jobs at sustainable companies (temporary layoffs, shorter working hours) and others intended to shore up income for the most vulnerable groups. In the Spanish government’s plan, these measures amount to close to 20 billion euros, or 1.6% of GDP. In other countries, such as the US and the UK, the budget plans also include tax cuts and public investments, so that the scale of their interventions is significantly higher (Exhibit 3). An added difficulty specific to Spain is the persistence of the high percentage of people on short-term employment contracts. For those individuals, the employment preservation measures are not as effective as for those with stable contractual arrangements as companies are reluctant to renew short-term contracts in an unfavourable economic climate. Moreover, Spain sees very significant temporary hiring volumes in the months of May and June to cover peak season needs in the tourism sector (nearly 400,000 people). Many of those hires will not take place this year due to the protracted duration of the impact on the sector. And, the individuals concerned will not benefit from the employment measures either.

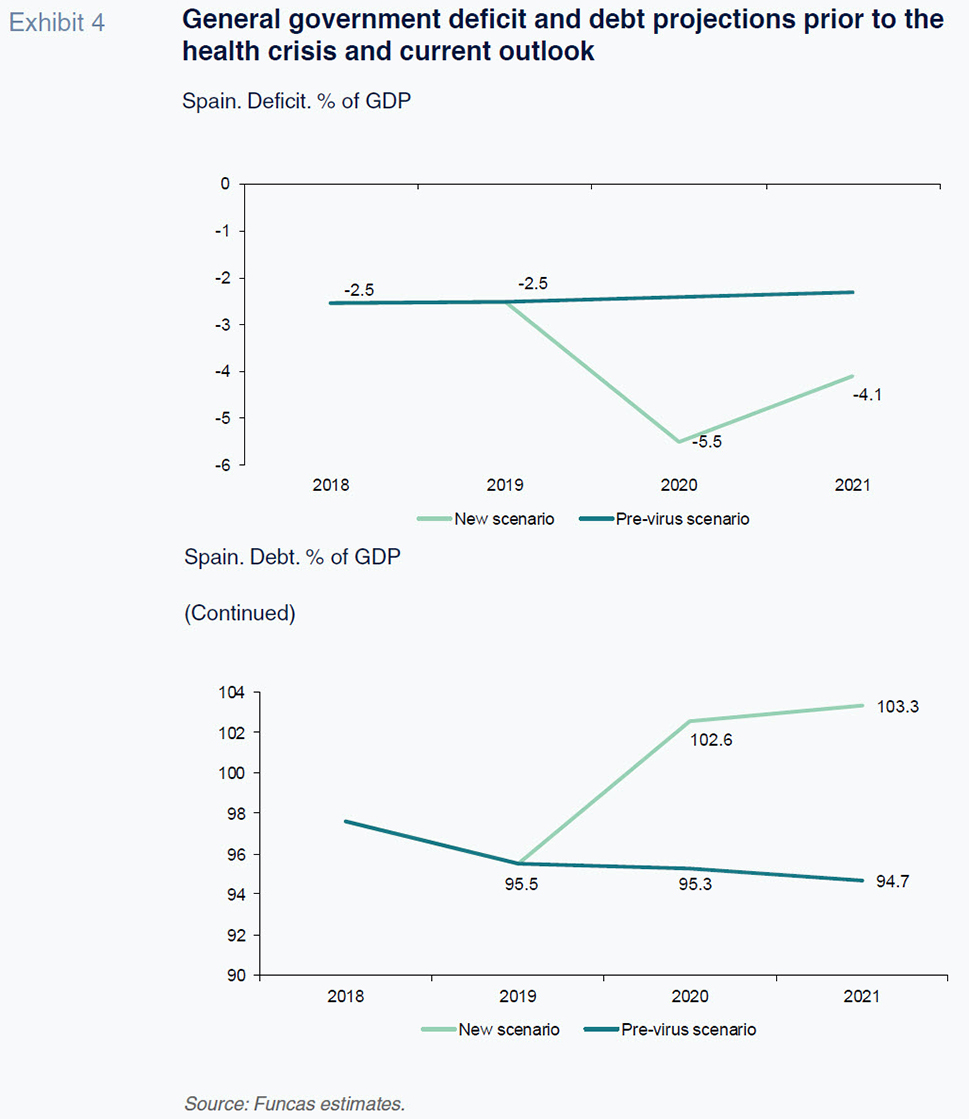

As a result, the deficit is expected to rise sharply, to 5.5% of GDP in 2020 (three points above the pre-crisis baseline scenario), due to the dual impact of erosion of the revenue base and growth in public expenditure as a result of the temporary shut-down in activity and the fiscal impact of the measures rolled out in response to the health crisis (Exhibit 4). Public debt will also reverse the moderate downward trend of recent years, rising to close to 104% of GDP, i.e., 10 percentage points above the baseline scenario forecast. The spike in public debt would be driven by the deficit incurred in 2020 and 2021 and the likely growth in liabilities as a result of the guarantees extended to certain companies which find themselves unable to repay their loans.

Another source of transmission risk, in addition to wider spread and a more protracted impact of the virus than modelled, is that the situation will translate into a financial and debt crisis, sending risk premiums wider. Here the European Central Bank has a key role to play, as was evident in the sharp recent increase in the Spanish country risk premium in the wake of certain remarks by the President of the ECB. However, the risk premium has since narrowed slightly, thanks to the 750 billion euro public and private bond repurchase programme announced by the ECB on March 18th.

Obviously, avoiding excessive widening of risk premiums is essential to helping states execute their health crisis response plans while keeping their productive structures poised for the foreseeable future recovery.

Conclusions and risks

In short, the pandemic is expected to have a severe impact on the Spanish economy, particularly during the first half of the year. Economic activity should recover during the second half, albeit without making up all the ground lost, so that Spanish GDP would contract by 3% in 2020. Although these estimates are less pessimistic than certain analysts’ predictions, they are based on the experience observed in Asian economies hit earlier by the virus, which are beginning to stabilise.

The biggest risk facing the Spanish economy is that the pandemic will prove longer-lasting than generally assumed. As already noted, these preliminary estimates are based on the assumption that the health crisis will start to improve from May, paving the way for relaxation of the emergency measures and lockdown and the normalisation of production chains. That is the situation being observed in countries which were at the epicentre of the crisis before it shifted to Europe. Logically, if fresh outbreaks of the virus were to occur during the Summer or subsequent months, the economy would suffer and the recovery would take longer to materialise.

Another area of uncertainty relates to the European Union’s response, which is vastly insufficient. Thus, in a recent survey targeted at many of the analysts who participate in the Funcas Panel, nearly all called for a greater role for European fiscal policy.

[5] The rollout of a Europe-wide emergency plan, financed by eurobonds, would be a step in the right direction. An initiative of that calibre, or greater involvement by the European Stability Mechanism, would be very welcome if the hardest hit countries, such as Italy, find it difficult to stabilize, unleashing a fresh wave of market tensions.

Notes

In particular, Royal Decree-Law 8/2020 (March 17th, 2020) on urgent and extraordinary measures for combating the economic and social fallout from COVID-19.

The latest measure announced was the 750 billion euro asset repurchase programme announced on March 18th.

See Capital Economics (2020). JP Morgan (2020) and Markets Insider (2020).

That trend is in line with other recent forecasting exercises, such as that of Deutsche Bank (2020).

References

Raymond Torres and María Jesús Fernández.

Economic Perspectives and International Economy Division, Funcas