The financial sector and economy in light of COVID-19: Situation and outlook for the autumn

The lax monetary environment, coupled with government initiatives, has enabled Spain’s banks to play a crucial role in tempering the effects of COVID-19. A key concern going forward, however, will be how long such interventions should continue and the extent to which they have fostered the emergence of a more dynamic business environment.

Abstract: While COVID-19 spurred the Fed’s decision to adopt an average inflation targeting regime, the ECB is more constrained in the way it can support the emergence of dynamic business growth. That said, it did launch the 1.35 trillion-euro Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) and has extended its targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). This lax monetary environment enabled the Spanish banks to increase their use of the ECB’s long-term financing facilities by 113.66 billion euros between March and July. In parallel, under specific schemes, such as the state-backed guarantees for business loans, corporate financing increased from a year-on-year rate of 1.1% in March to 6.1% in June. One of the most complex issues facing Spain is how long its extraordinary financing flows should continue so as not to significantly impair overall asset quality. Although non-performance has held steady at around 4.7%, this metric is expected to deteriorate throughout the rest of 2020 and much of 2021, with the magnitude of the rise in NPLs dependent on the continuation of the furlough scheme, speed of the economic recovery, and lingering uncertainty regarding COVID-19. Nevertheless, the crisis could prove an opportunity for Spain if public and financial intervention results in higher levels of business dynamism.

[1]

Introduction: Changes in the monetary environment and bank resilience

The summer of 2020 has been dominated by a complex interplay of expectations of an economic rebound overshadowed by the threat of a second wave of infections. In the financial arena, markets have been volatile. The banks have been very active in providing businesses with credit, a role which, coupled with other financial relief and job protection measures sponsored by the state, has constituted one of the key responses to the crisis.

The monetary climate has also been influenced by the central banks’ response. Already very lax before the pandemic, monetary policy has become even more expansionary in recent months. The most significant change came at the Jackson Hole Symposium, organised by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City on August 27th and 28th. During his speech, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, announced a major policy shift, signalling that the Fed would from now on pay more attention to job growth than a rigid inflation target. In fact, he specifically said the Fed would allow inflation to run over the target of 2%. He also acknowledged that the policy shift implied that the current expectation is that interest rates will remain at low levels in the long run. Going forward, the Fed plans to pursue “average inflation targeting”, such that it will let inflation run “moderately” above the 2% goal if that helps keep unemployment at reduced levels.

That shift in US monetary policy adds to the debate about the balance between the policies pursued by the central banks on either side of the Atlantic. While the European Central Bank’s (ECB) actions have also been clearly expansionary in recent years, the expectation of lower rates for even longer in the US, coupled with other factors of a more institutional nature, have driven dollar depreciation relative to the euro. Now the Fed’s actions signal a longer horizon of low rates as well as greater flexibility in implementing monetary policy. The ECB, however, cannot in theory make such a substantive change to its mandate because it is legally more bound by an inflation target. The ECB has, however, been providing almost unconditional support in the form of liquidity, even more so since the onset of the pandemic. At its meeting on September 17th, 2020, the European monetary authority opted to leave the interest rate on the main refinancing operations and the interest rates on the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility unchanged at 0.00%, 0.25% and -0.50% respectively. It also reiteratred the extension of its 1.35 trillion euro Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). It expects to continue to repurchase assets under that programme until at least the end of June 2021 and in any case until the ECB “judges that the coronavirus crisis phase is over”. The Governing Council also said it would reinvest the maturing principal payments from securities purchased under the PEPP until at least the end of 2022. Additionally, the ECB also agreed to continue its targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III).

That monetary easing is providing the banks with sizeable liquidity at a time when many banks are participating in government financing programmes aimed at kick-starting the economy. The goal is to prevent an even bigger economic contraction than that caused directly by the lockdowns and the resulting drop in consumption and investment. Importantly, these programmes aim to avoid non-payment among companies which end up driving an increase in non-performance. However, the ultra-low interest rates remain a huge challenge for the bank intermediation business. Now that the markets are expecting interest rates to remain ultra-low for even longer than thought before the pandemic, the challenge has only increased.

Nevertheless, the ECB believes that the banks under its supervision remain well capitalised, enabling them to lend money to the private sector despite the potential difficulties and losses inflicted by COVID-19. On July 28th, 2020, the ECB published the results of its COVID-19 Vulnerability Analysis of the 86 banks it supervises directly under the scope of the Single Supervisory Mechanism. The aim was to identify the sector’s potential vulnerabilities over a three-year horizon. The results suggest that the eurozone banking sector is capable of withstanding the stress triggered by the pandemic. The banks’ average aggregate common equity tier-1 (CET1) ratio would decline by approximately 1.9 percentage points in the ECB’s baseline scenario to 12.6% and by 5.7 percentage points in the adverse scenario to 8.8% by year-end 2022.

Recent Bank of Spain data also indicate that Spanish banks are headed into the pandemic from a far better capital adequacy position compared to the last crisis. Specifically, Spain’s central bank published its supervision statistics for the banks for the first quarter of 2020 on July 30th. The banks operating in Spain presented a total capital ratio of 15.69% as of the first quarter, demonstrating, according to the authority, significant stability with respect to the levels reported for the first and fourth quarters in 2019, which stood at 15.45% and 15.94%, respectively.

Financing: Recent trend and outlook

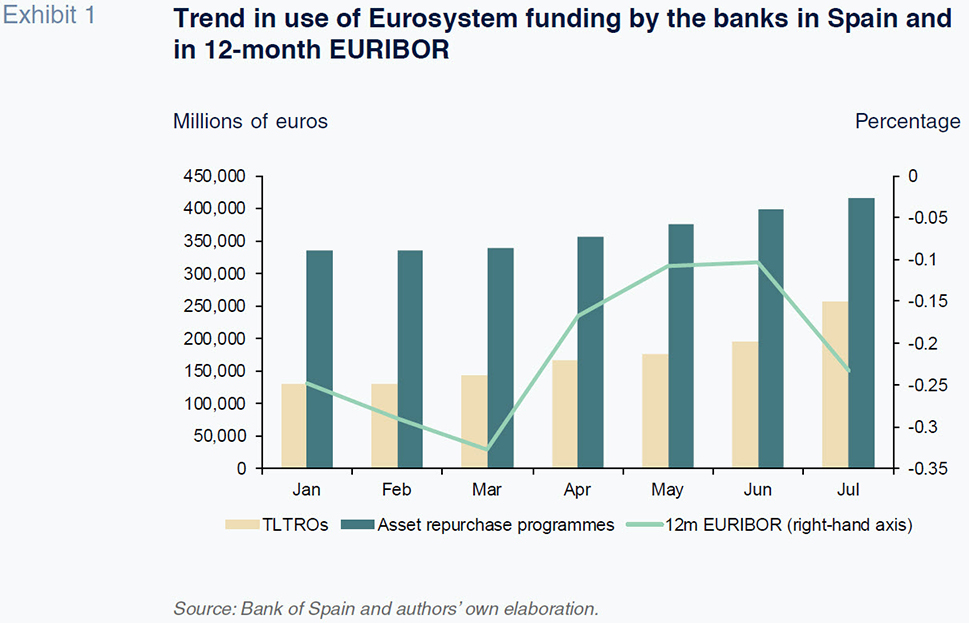

The Spanish banks, like their European counterparts, have been affected considerably by the uncertain economic outlook and the ECB’s monetary response. Between the onset of the pandemic in March and July, the Spanish banks increased their use of the ECB’s long-term financing facilities (mainly via TLTROs) by 113.66 billion euros (Exhibit 1). During the same timeframe (not shown in the exhibit), the eurozone banks as a whole drew down 939.5 billion euros under those same facilities. Use of the asset repurchase programmes has also increased considerably by 76.13 billion euros in Spain and 538.13 billion euros in the eurozone. One of the consequences of the increase in liquidity has been a sharp drop in interbank rates, particularly in recent months, following confirmation of the expansion and extension of the central banks’ expansionary measures. 12-month EURIBOR had traded to -0.103% in June but fell back to -0.233% in July. The most recent data available put 12-month EURIBOR at an all-time low of -0.359% in August.

The banks’ support in the form of lending activity, thanks in part to state-backed guarantee schemes, is one of the bright spots in this harsh crisis. In Spain, the most noteworthy programme is the 100-billion-euro business loan scheme backed by guarantees shared between the banks and the public credit institute, the ICO. The fifth and last tranche of the surety lines comprising this scheme was approved on June 15

th. However, on July 3

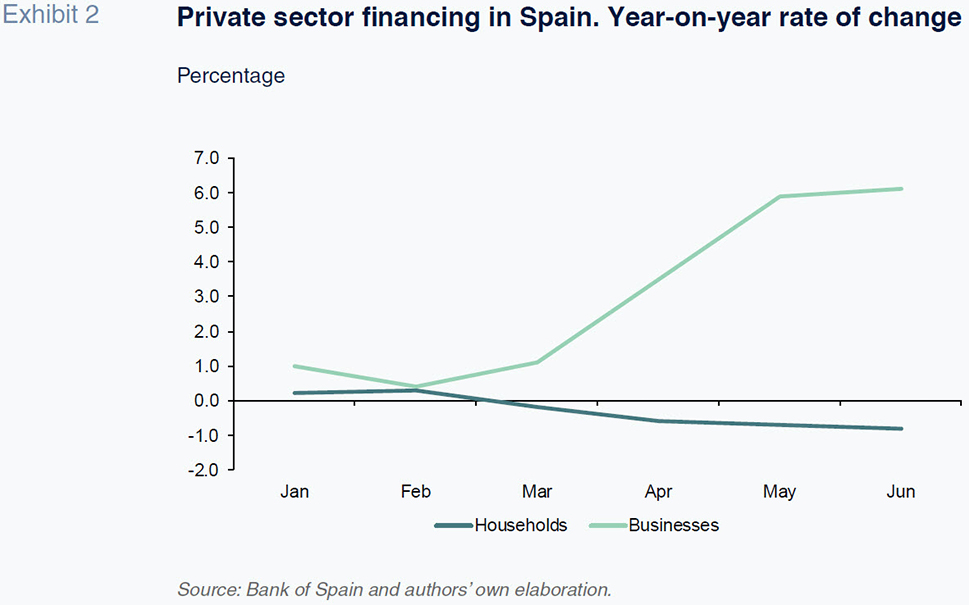

rd, the Spanish Cabinet approved a new guarantee programme, with an envelope of 40 billion euros, earmarked for new business investment projects focused on environmental sustainability and digitalisation. That same day it also approved a new 10 billion euro fund to be managed by SEPI, the Spanish state’s industrial investment holding company, to provide financial support for applicant non-financial corporates that are “strategically solvent” but have been hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 crisis. This general trend is evident in private sector lending activity in Spain. As shown in Exhibit 2, bank lending to the private sector in Spain increased from 1.1% year-on-year in March to 6.1% in June (most recent figure available), and is expected to have risen further in July and August. Household financing, however, fell over the same period. It was already declining by 0.2% year-on-year in March, a contraction that widened to 0.8% in June.

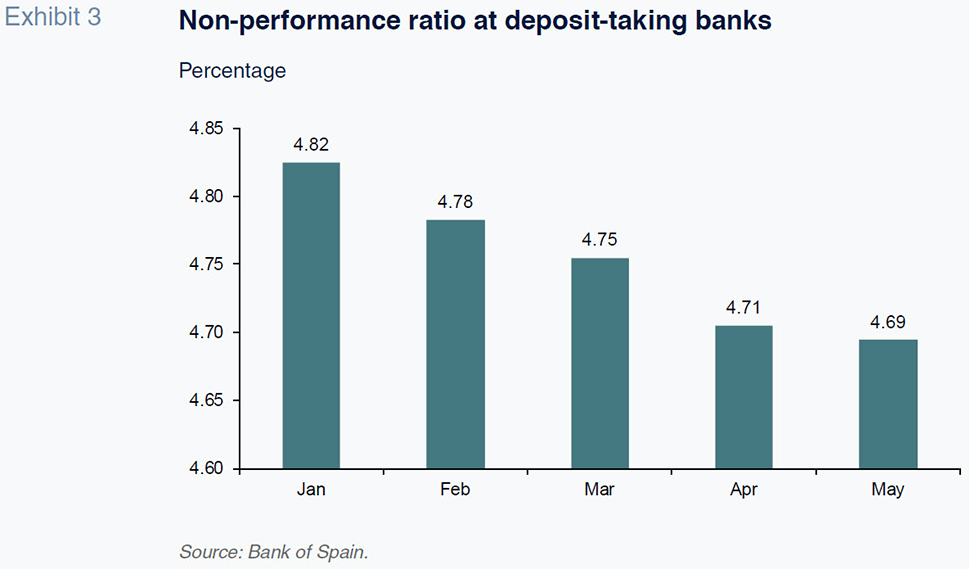

One of the most complex issues facing Spain and other countries with similar business support programmes is how long those extraordinary flows of financing should be left in place so as not to significantly impair overall asset quality. Up until May, as shown in Exhibit 3, Spain’s deposit takers had not experienced a significant increase in non-performance. To the contrary, the non-performance ratio decreased from 4.75% in March to 4.69% in May. However, non-performance tends to be a lagging indicator, particularly when employment is a significant victim. Although jobs have taken a hit in Spain, the financing extended by the banks, coupled with the state furlough scheme, has stemmed the rise in unemployment. Nevertheless, the expectation is that non-performance will deteriorate throughout the rest of 2020 and much of 2021, although by how much remains to be seen. The magnitude of the increase is likely to depend crucially on how long the furlough scheme can be left in place, the speed of the economic recovery and the dissipation of uncertainty regarding the health consequences of COVID-19.

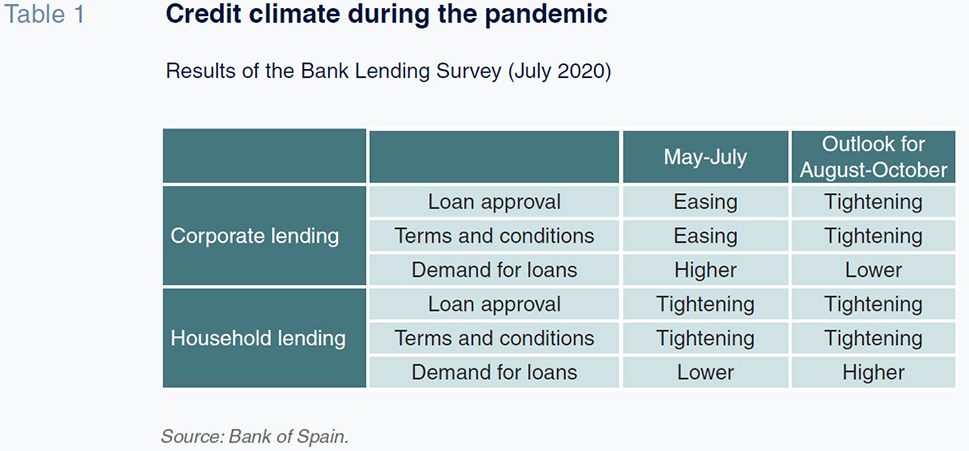

In the current circumstances, all projections are a moving target. For example, the Bank Lending Survey conducted by the Bank of Spain in July revealed an easing in business loan approval terms since May, as well as growth in demand. At that same time, however, the entities polled said they expected tighter loan approval conditions and a drop in demand over the coming months. It is hard to corroborate that prediction in an environment in which many companies are going to continue to need financing and the state-backed guarantee schemes may be left in place for longer than initially anticipated. Asked about household lending, which was contracting at the time, the banks said they expected demand to rise, a prediction that will ultimately depend on the pace of economic recovery. One of the fears instilled in many countries is that COVID-19 may have a more permanent contractionary effect —or “belief-scarring effects”— on private sector spending and investment than initially contemplated.

[2]

Conclusions: Financing and corporate regeneration

Spain’s business landscape faces a dual reality this autumn. In Spain, many firms that were viable before the onset of the pandemic have taken advantage of state-guaranteed bank loans and/or furlough schemes. However, any fresh supply or demand shocks would have highly adverse ramifications for them. Even assuming more moderate COVID-19 caseload scenarios, non-performance is bound to increase. The rate at which it does so will be key. In order to nurture the economic recovery, the goal is to keep defaults and business destruction at a minimum. If not possible, then the goal needs to be to restructure and manage that debt adequately. Bank financing must not grind to a halt, as bank lending is set to play an essential role in the economic recovery in the months and years to come.

A parallel aspect of considerable importance is the expected arrival of European funds in 2021 and 2022, which, in addition to national budget allocations for combatting COVID-19, will provide a boost to investment which must be channelled appropriately and complemented by the banks’ lending efforts.

The banks will be called on to help manage the complex interplay of consumption, employment and financing uncertainties intrinsic to this pandemic. The tricky part is the need for business dynamism. Every crisis requires redirecting funds from the firms that fail to those that survive or emerge. The process of business creation-destruction was violated during the last crisis by allowing non-viable companies to continue to operate for too long. Dynamism can also be achieved by incentivizing much of the productive structure towards activities that foster greater digitalisation, sustainability and innovation. That debate is not exclusive to Spain. At the Jackson Hole Symposium in August, one of the topics most hotly debated was the extent to which the business dynamism triggered by previous growth cycles, mainly during the last century, is slowing. It is possible that, paradoxically, the current predicament, marked by considerable public and financial sector intervention, is also a unique opportunity. The current challenges call for responsibility from the banks but also from government. The banks need to keep the economic wheels turning but can only do so if they focus their resources on sustaining or reviving that which can grow and survive rather than wasting resources on those firm in decline or already doomed to fail. When state guarantees are provided, the same criteria should prevail.

Notes

At the time this article was published, the merger between CaixaBank and Bankia was announced and subsequently approved. In the coming months, we plan to assess this development as part of broader structural changes in the Spanish banking sector as more information becomes available.

Santiago Carbó. CUNEF, University of Granada, Bangor University and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez. University of Granada and Funcas