Spain’s macro outlook: Rising COVID-19 cases dampen economic forecasts

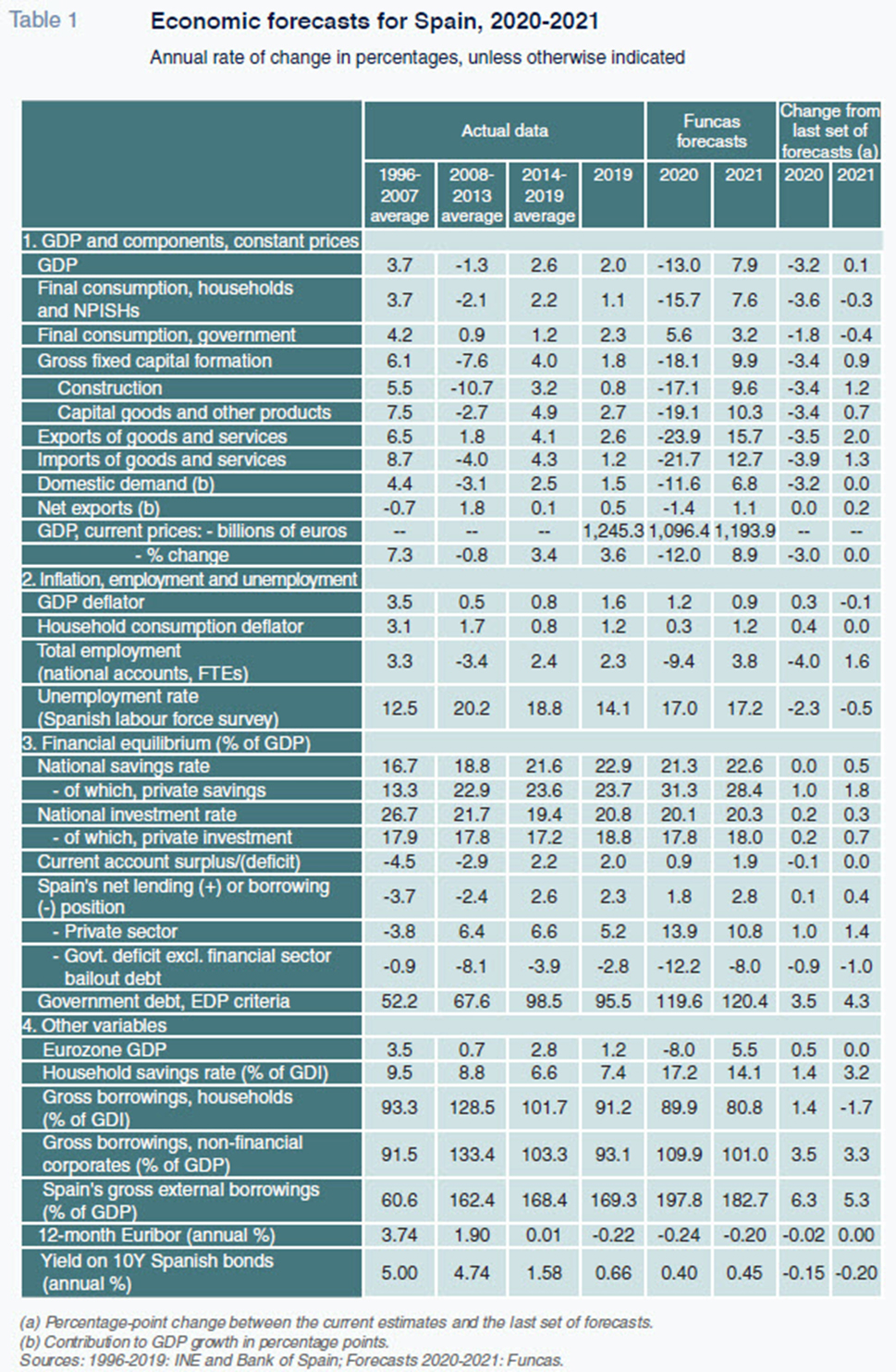

In the context of controlled growth in COVID-19 cases and sluggish performance in key sectors, such as tourism, a downward revision of Spain’s forecasts shows a 13% contraction expected for 2020, with pre-COVID growth levels unlikely to return before 2023. The European recovery fund could support Spain’s recovery, but its impact will be limited and short-lived, unless it is accompanied by key reforms.

Abstract: According to provisional data, Spanish GDP fell by 18.5% in the second quarter. Even after taking into consideration the weight of vulnerable sectors, such as tourism, Spain’s contraction would still exceed that of Germany’s. Looking forward, the economic recovery will be both unequal and surrounded by uncertainty. Assuming controlled growth in COVID-19 cases, an avoidance of lockdown, as well as the prolongation of expansionary macroeconomic policies, GDP is expected to contract by 13% in 2020, which is 3.2 percentage points below the last set of forecasts. Although GDP is forecast to grow by 7.9% in 2021, the economy will not fully recover to pre-COVID GDP levels until at least 2023. The ongoing crisis will adversely impact the number of hours worked, but the furlough scheme and redistribution of work will cushion the blow in terms of jobs. Significantly, Spain could receive almost 140 billion euros from the European recovery fund. However, the impact of these funds will depend largely on reforms in areas such as the labour market, education, the digital and energy transition, and in general measures that help close Spain’s productivity gap with the EU. Moreover, there are upside and downside risks that could either support or undermine Spain’s recovery, such as the rollout of a vaccine or a rise in NPLs that could reduce banks’ lending capacities.

The recovery stalled in August

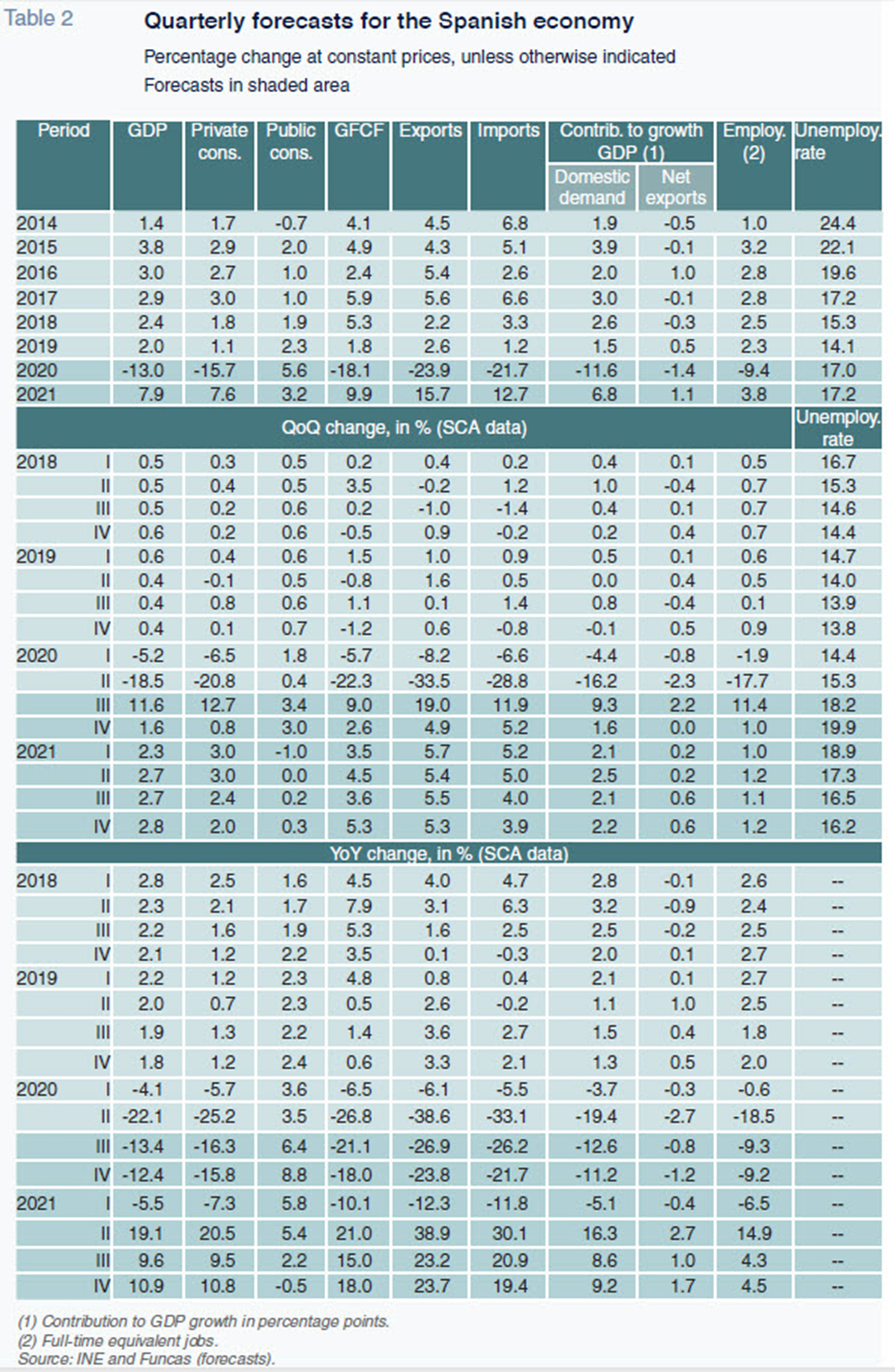

According to provisional data, Spanish GDP contracted by 18.5% in the second quarter. Except for public spending, all components of demand registered hefty declines. Tourist service exports collapsed by an overwhelming 91.6%. On the supply side, only the agriculture sector registered growth. The biggest contractions were sustained, as expected, in the sectors hardest hit by the restrictions imposed to curb the spread of the pandemic, i.e., retail, transport and hospitality, whose gross value added (GVA) shrank by 40.4%, while artistic, leisure and cultural activities registered a decline of 33.9%.

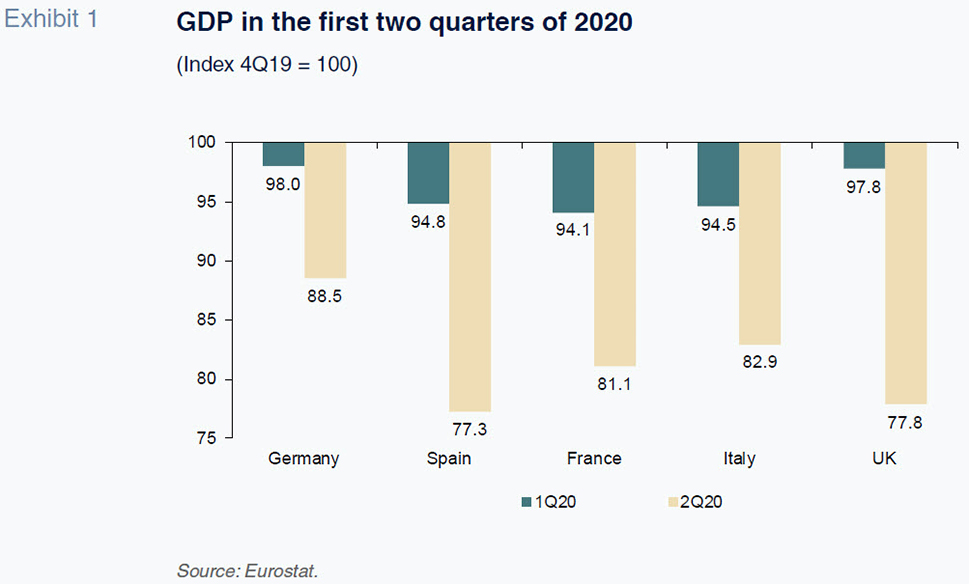

The contraction in Spanish GDP was among the highest in Europe (Exhibit 1). That is partially attributable to the weight of tourism and other sectors adversely affected by the pandemic. Those sectors account for 28% of Spanish GDP, which is more than manufacturing, construction and the primary sectors combined. Excluding those vulnerable sectors, Spanish GDP would have contracted by 10.9%, which is still well above the decline registered in other countries, such as Germany.

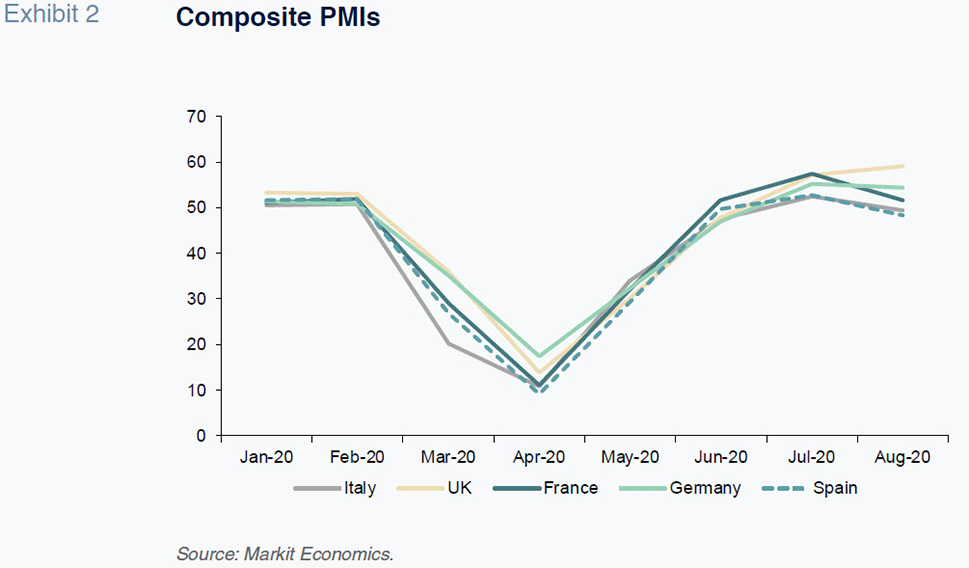

GDP hit bottom in April and embarked on a recovery from May, as the controls rolled out to curb the pandemic were eased, with momentum peaking in July. However, the reintroduction of restrictions in numerous places due to the proliferation of COVID-19 clusters has taken a toll on the recovery in August. GDP may even have contracted again in August judging by the fallback in the PMI readings and confidence indicators as well as the halt in the rebound in spending indicated by card payments (Exhibit 2).

The construction sector, which at the onset of the crisis was second only to the hospitality sector in terms of impact, has been the fastest to recover. The tourism sector, however, following its total shutdown in April and May, has remained very depressed, far below normal levels of activity and also below expectations at the time of our last set of forecasts. That situation has been shaped largely by several countries issuing recommendations not to travel to Spain and introducing quarantines upon return as a result of the rising case numbers. In July, the number of overseas tourist arrivals was 2.5 million, compared to 9.8 million in July 2019.

The number of Social Security contributors also experienced significant growth in July, with people leaving the furlough scheme to return to work. At the end of August, 812,000 employees remained in that scheme, compared to a peak of 3.3 million at the end of April.

In short, GDP growth in the third quarter is estimated at around 11.6%, which would imply the recovery of almost 40% of the activity destroyed during the previous two quarters. In the most affected sectors, that recovery is expected to be a much lower 13%, compared to 75% for the rest of the economy.

Downward revision of 2020 forecasts

The current forecasts assume controlled growth in COVID-19 case numbers such that a widespread lockdown can be avoided. We assume that the virus will, however, continue to dissuade people from travelling and that activity in the sectors most dependent on human contact will continue to suffer. The forecasts assume that the efforts to control the pandemic will prove effective, facilitating a gradual return to a degree of normalcy in 2021, particularly in the tourism sector, but that mass vaccination will not happen before the end of next year, in line with recent statements by the WHO.

The forecasts also assume expansionary macroeconomic policies throughout the projection horizon. Thanks to the ECB’s intervention, interest rates can be expected to remain at low levels and the markets should remain open to public debt placements. We expect fiscal policy to remain expansionary due to the business liquidity and job support measures, and growth in spending in line with the European recovery package (which has been factored into the projections, albeit limited in amount to 14 billion euros in 2021, out of the total of 140 billion euros).

Framed by these assumptions, we are forecasting a GDP contraction of 13% in 2020. That estimate masks two starkly different realities: in the sectors associated with tourism, leisure and culture, GDP will contract by 35.5%, with the rest of the economy shrinking by 4%.

That forecast is 3.2 percentage points worse than in our last set of forecasts (Table 1). As mentioned, the downward revision is the result of the surge in case numbers and the dissuasive effect it has had on foreign tourist arrivals. We are now estimating that tourism will generate 25 billion euros less revenue in 2020 than we were forecasting in July. The fresh rise in case numbers has also had an adverse effect on business and consumer sentiment due to the fear of a new lockdown. Altogether, the tourism crisis is responsible for two-thirds of the downward revision to our estimate; the rest is due to the impact of the increased uncertainty on internal demand.

We would single out the sharp estimated contraction in investment, of close to 18%, with heightened turbulence clouding visibility for businesses. Consumption is also set to contract significantly (by around 16%), undermined by falling household income in the context of furloughs and job losses, and an increase in precautionary savings

versus expenditure. We expect savings to surpass 17% of disposable household income, a record high. Public expenditure is the only component of demand expected to grow.

External demand is expected to detract from growth due to the downturn in tourism and, to a lesser degree, the drop in exports of goods and non-tourism services. Imports, meanwhile, are also expected to trend lower, although by less than exports.

The rebound anticipated for the end of this year will be felt in 2021. We are forecasting GDP growth of 7.9% in 2021, which is slightly higher than in July. However, by the end of next year, Spanish GDP will still be 3.9% below pre-COVID levels if those forecasts materialise. In all probability, the economy will not fully recover to pre-COVID GDP levels until 2023, and maybe even 2024, depending on the path of economic policy (more on that below).

Internal demand, led by investment (thanks to fiscal stimulus measures and the European recovery package), is expected to drive the recovery. As the case numbers start to improve and the prospect of a vaccine nears, households and business are likely to become more inclined to spend and replace their productive capital. Trade will also make a positive contribution, prompted by the gradual renewal of tourist activity and growth in both exports and imports of goods.

Despite the collapse in tourism, the external accounts are expected to present a surplus throughout the forecast horizon, thanks to the drop in imports triggered by the recession. Exports should recover in 2021, fuelled by

the anticipated rebound in global trade and the gradual normalisation of tourist-related flows.

The deepening of the crisis will affect the number of hours worked, which are expected to trend downward, in line with growth. However, the impact on jobs is expected to be cushioned by the furlough scheme and the redistribution of work (translating into fewer hours worked per job holder). Nearly 200,000 people are expected to exit the labour market in 2020, due to discouragement and/or the difficulty in finding work during a pandemic. All of which is expected to mitigate the fallout from the crisis on the unemployment rate which is forecast at 17% in 2020 on average (19.9% in 4Q20). Adding in furloughed employees, whose pace of reincorporation is likely to slow considerably in the fourth quarter (by year-end an estimated 300,000 employees could remain under the scheme), unemployment in the fourth quarter would amount to 21%.

Although the trend in unemployment is significantly less adverse than in earlier recessions, the enabling formulae (furlough scheme and shorter working hours) may eventually result in job losses.

In 2021, business volumes are likely to remain well below pre-pandemic levels at many companies so that when the furlough scheme runs out and firms decide to reinstate normal working hours, it is foreseeable that a certain number of workers will lose their jobs. However, these job losses will be more than offset by job creation driven by the gradual economic recovery. Consequently, the quarterly trend in job-seeker numbers in 2021 will be shaped by the timing of the withdrawal of that scheme. Assuming that the impact of its withdrawal is gradual, the unemployment rate would trend lower to an estimated 16.2% by the end of 2021, equivalent to around 600,000 job-seekers more than before the crisis. However, the annual average in 2021 could be higher than that of 2020 due to the high level of unemployment projected at the start of the year.

Turning lastly to the public finances in 2020, the surge in public spending (estimated at 26 billion euros) and the collapse in tax revenue (72 billion euros) are expected to drive the public deficit to over 12% of GDP. The 2021 estimates factor in decisions already taken or announced (minimum income scheme, growth in public investment in keeping with the European investment plan). The result of those assumptions, coupled with the interplay of the automatic stabilisers, would be a reduction in the deficit, essentially the cyclical component, to 8% of GDP. Public debt, meanwhile, is expected to stagnate at high levels of close to 120% of GDP.

The European recovery plan

One of the biggest game-changers affecting this set of forecasts is the agreement by the European Council in July on an EU recovery package. By some estimates, of the 750 billion euros earmarked to the plan, Spain could receive around 140 billion euros, more than half in the form of direct grants and the rest in loans

[1].

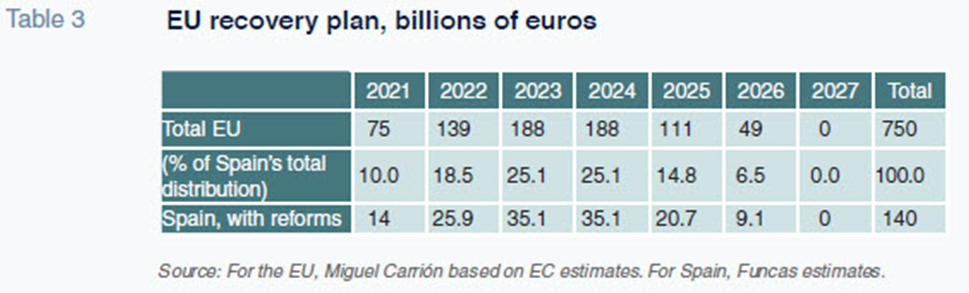

As already mentioned, the forecasts for 2021 factor in the receipt next year of 14 billion euros from Europe, which is just a small percentage of the funds Spain may ultimately qualify for. Execution of the programme is expected to accelerate in subsequent years (Table 3)

[2] , but the effective size of the disbursements will depend on the Spanish authorities’ management and implementation capabilities and the nimbleness of the European apparatus with respect to the required procedures, usually plagued by bureaucracy that makes them slow, complex and, as a result, unpredictable. An analysis of the current European budget period (2014-2020) shows that Spain has only spent 34% of the more than 56 billion euros available in structural funds

[3]. Accordingly, in the absence of organisational improvements and project formulation, monitoring and execution process reform, Spain risks only being able to attract a portion of the funds available for 2021-2027.

Elsewhere, the impact of the European grants and loans will depend largely on reforms designed to facilitate their use (in addition to measures aimed at improving fund management in Spain and speeding up bureaucracy in Brussels). These reforms coincide with those needed by Spain to address its main economic and social imbalances (education, job market, pension system and the digital and energy transition). According to a number of studies, the reforms are vital to closing the productivity gap with the rest of the EU, which is widening by 0.2 percentage points every year.

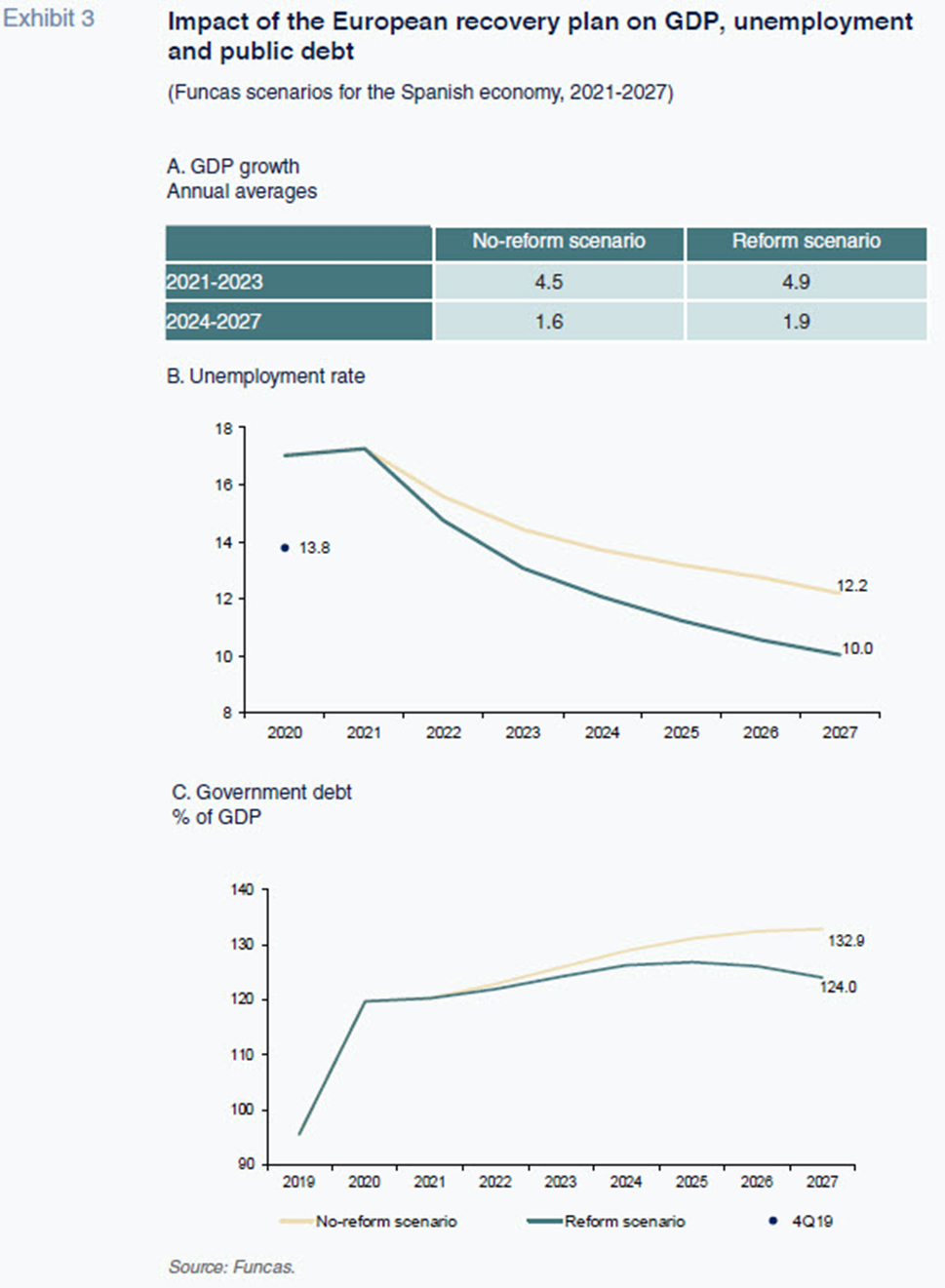

To analyse the impact of the recovery funds on the economy with and without reforms, we have modelled two scenarios over the budget period: 2021-2027 (Exhibit 3). Both assume administrative improvements to mobilize projects and speed up funding approval in Brussels.

The first scenario —status quo— assumes receipt of the European funds in the absence of reforms aimed at reducing Spain’s economic and social deficits. The aid would lift GDP via fiscal stimulus measures and public investment. However, in the absence of reforms, the growth from the increase in public spending would be transitory, and GDP growth would trend towards its inertial rate (estimated at 1.6% per annum). The result is an incomplete recovery, an unemployment rate above pre-crisis levels until 2024 and continuing steady growth in public debt, which would reach 133% of GDP in 2027.

In the other scenario, in addition to factoring in the European funds, we assume reforms designed to close the productivity growth gap with the rest of Europe and to reduce unemployment and job precariousness. As a result, the fiscal stimulus measures would provide GDP with a temporary boost, as in the status quo scenario, but also lift potential output to 1.9% per annum. Unemployment would come down to 10% by 2027 and the upward trend in public debt would revert, ending the period at an estimated 124% of GDP. Nevertheless, that level is still too high, signalling the need for a budget consolidation plan once the growth trajectory is on solid footing (an effort not modelled in this simulation).

Opportunities and risks

These estimates are marked by a considerable level of uncertainty, with both downside and upside risks. The rollout of a safe and quickly implemented vaccine would dissipate some of the main doubts about the recovery. Confidence would improve substantially, facilitating a reduction in precautionary savings and growth in both internal and external demand. However, it is likely that the pandemic will have accelerated some of the structural changes that pre-date the crisis: shifts in consumption patterns, digitalisation, preference for short production cycles and growing climate change awareness. That means that even if the COVID-19 crisis is remedied, the Spanish economy will still face significant structural challenges.

Another potential boon, already referred to, could come from a new state budget designed to foster the recovery and tackle those structural challenges, coupled with the rollout of reforms and a plan for reducing the imbalances in the public finances in the medium-term. That budget will also be crucial to making the most of the European funds.

On the downside, it is important to monitor the impact of the crisis on the financial sector. An increase in non-performing loans could oblige the banks to step up their provisioning efforts, thereby reducing already-slim margins and curbing the provision of new credit. The markets could also become less benevolent if, despite the burgeoning deficit, the growth targets fail to materialise. That situation could drive an increase in the country risk premium, making it more expensive for the Treasury to raise debt.

Longer-term, the main threat is that the Spanish economy could fall behind its European partners. Since Spain joined the European Union, growth in its per-capita income has tended to outpace the European average. That convergence came to a halt with the recession of the early 90s and again with the financial crisis, albeit recovering with newfound momentum during recovery phases. On this occasion, however, the effort required is unparalleled. Never before has Spain faced such a huge economic challenge of having to tackle two policy fronts at once. On the one hand, Spain must manage the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic, an effort that requires curtailing the closure of numerous companies that are on the verge of bankruptcy and the loss of thousands of jobs that are currently being propped up —in an increasing number of cases artificially— by furloughs and shorter working hours. On the other hand, Spain’s foundations need to be laid for inclusive growth, an effort that requires reforms that were put off during the expansionary period, and improved project management processes so as to make the most of the European funds.

Notes

Raymond Torres and María Jesús Fernández. Economic Perspectives and International Economy Division, Funcas