Resilience of Spanish households to the economic fallout from COVID-19

Although overall household indebtedness has fallen below the eurozone average in Spain, certain subsegments of Spain’s population remain financially vulnerable. With the Bank of Spain forecasting a rise in the unemployment rate to 22.1% in 2021 under its worst-case scenario, vulnerable groups such as those with lower levels of education, households headed by a single parent, and youth will require targeted measures to protect them from the adverse consequences of COVID-19.

Abstract: At first glance, it appears Spain entered the COVID-19 crisis in a relatively good position. The household leverage rate had fallen below the eurozone average, reducing the amount of income Spanish households earmarked for debt service payments from 11.7% of their disposable income in 2008 to 6.1% at the end of 2019. Yet, 33.9% of Spanish households would be unable to deal with an unexpected expense of only 700 euros, which is higher than the EU-27 average. When analysed based on metrics such as age, gender, household composition, and geography, it becomes clear that there are certain groups particularly vulnerable to the economic effects of COVID-19. For example, among those with a lower secondary education, 47.8% of individuals would be unable to deal with an unexpected expense. Similarly, 53.7% of households headed by a single adult and 46% of households composed of a single woman would struggle. Notably, those aged between 16 and 24 present the highest percentage of an inability to deal with an unexpected expense, while 31.7% of this group are ‘at risk of poverty or social exclusion’, 6.4 percentage points above the overall average. For these reasons, targeted government measures that rely on intergenerational generosity would be required to successfully exit this crisis.

Introduction

All forecasts indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic will have a significant economic impact on GDP and employment at the international level, with first-half 2020 figures suggesting Spain will be one of the hardest hit economies. To cushion the fallout from the crisis, the measures implemented in Spain have concentrated on propping up business and household income so that aggregate demand suffers as little as possible. Given that certain sectors and individuals are especially vulnerable, a number of targeted measures have been channelled to specific industries such as the tourism and retail sectors (in some instances extending the furlough scheme) and to lower-income individuals (moratoria on mortgages and rent, social vouchers, temporary subsidiaries, suspension of evictions, lunchroom vouchers for children, etc.).

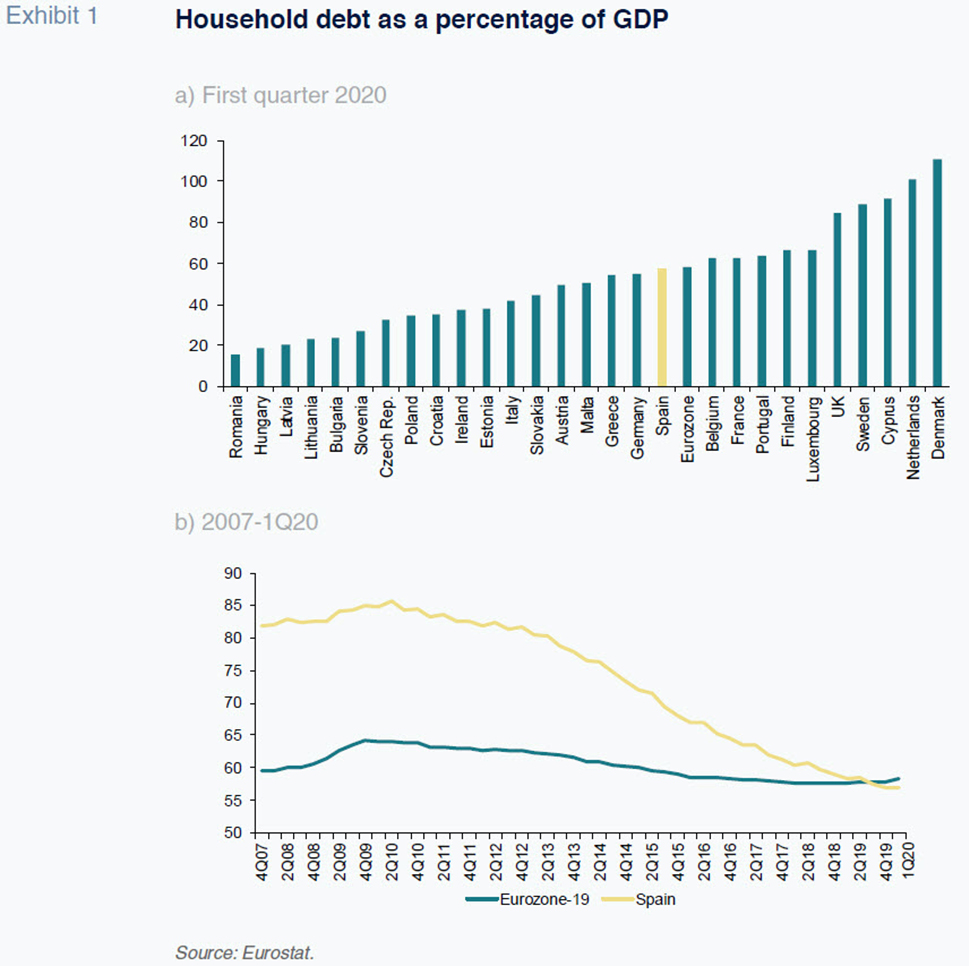

Fortunately, the Spanish economy had been growing steadily since emerging from the Great Recession, outpacing eurozone average growth since the second half of 2013. As a result, unemployment fell by 12 percentage points to 14.1% by the first quarter of 2020. In parallel, household debt decreased from a peak of 85.6% of GDP in June 2010 to 56.9% by March 2020, below the eurozone average of 58.3%. The combination of the drop in unemployment, growth in disposable income and reduction in leverage is good news in terms of the ability of Spain’s households to weather the effects of the COVID-19 crisis.

However, according to the National Statistics Office’s (INE) Living Conditions Survey, a considerable percentage of Spanish households would face serious difficulties in dealing with unexpected but relatively small rises in expenses. In the most recent survey of household well-being, 33.9% of all households said they would be unable to face an unexpected expense of 700 euros. Relatedly, 25.3% of the population is at risk of poverty or social exclusion. For those highly vulnerable people, the impact of the prevailing crisis is far greater.

The purpose of this paper is to analyse Spanish households’ ability to withstand the impact of COVID-19 in the European context, using certain indicators of economic vulnerability. In the case of Spain, the wealth of information available permits an analysis of the differences in resilience as a function of variables such as age, level of education, nationality, gender, etc.

The results indicate that many groups are highly vulnerable from an economic standpoint and therefore should be specially targeted by measures designed to cushion the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. Young people have been hit particularly hard. They have a higher percentage at risk of poverty and are disproportionately affected by job destruction. Youth unemployment had increased sharply to 39.6% by the second quarter of 2020. Consequently, government aid needs to include generation-specific measures, with a focus on youth job creation instruments.

Recent trend in household leverage

Prior to the bursting of the housing and credit bubble in 2007, household debt had risen significantly in Spain. However, Spain’s households have since deleveraged. Indeed, the household leverage rate has fallen to 56.9%, similar to 2003 levels. The deleveraging effort has been such that Spain has not only eliminated the gap with respect to the eurozone (which peaked at 22.9 percentage points in mid-2008), but it has also seen household leverage dip 1.4 percentage points below the eurozone average. Among the EU-28, Spanish households are less leveraged than their counterparts in France (62.5%), Portugal (63.9%), the UK (84.3%) and the Netherlands (101.1%), but slightly more indebted than those of Germany (54.9%) and Italy (41.6%). As a result, the intense deleveraging effort of recent years and the current leverage ratio put Spanish households in a relatively good position to weather the fallout from COVID-19.

Thanks to that deleveraging effort, Spain’s households have gone from earmarking 11.7% of their disposable income to debt service (interest and principal repayment) in 2008 to 6.1% by the end of 2019, a level very much in line with that observed in Germany and below the levels recorded in France (6.4%), the US (7.9%) and the UK (9%). Of the countries for which the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) provides information, only Italy’s households bear a lower debt burden than Spain’s. The deleveraging effort, the drop in interest rates and the growth in disposable income explain the decline in the debt service requirement. Note that the stock of household debt in Spain is currently equivalent to 90.4% of disposable income, which is back at the levels of 16 years ago.

The resilience of Spain’s households in the European context

Although the overall picture painted by the leverage and debt data suggests that Spain’s households are headed into this crisis from a position of relative strength, that image needs to be rounded out by more detailed analysis of the population groups that are more vulnerable as a result of lower disposable income, higher indebtedness, or a combination of both.

The Living Conditions Survey asks a question of particular interest in terms of analysing household readiness for the crisis. Specifically, the considered households’ ability to deal with an unexpected expense. In the most recent survey, conducted in 2019, the respondents (households) had to answer yes or no to whether they could deal with an unexpected expense of 700 euros (it had been 650 euros in prior years and a little less before 2011) from own resources, i.e., without asking for a loan or relying on credit. Importantly, unexpected expenses can come in many forms, e.g., covering a surgical procedure, paying for funeral and burial expenses, a major household repair, the need to replace a domestic appliance, etc.

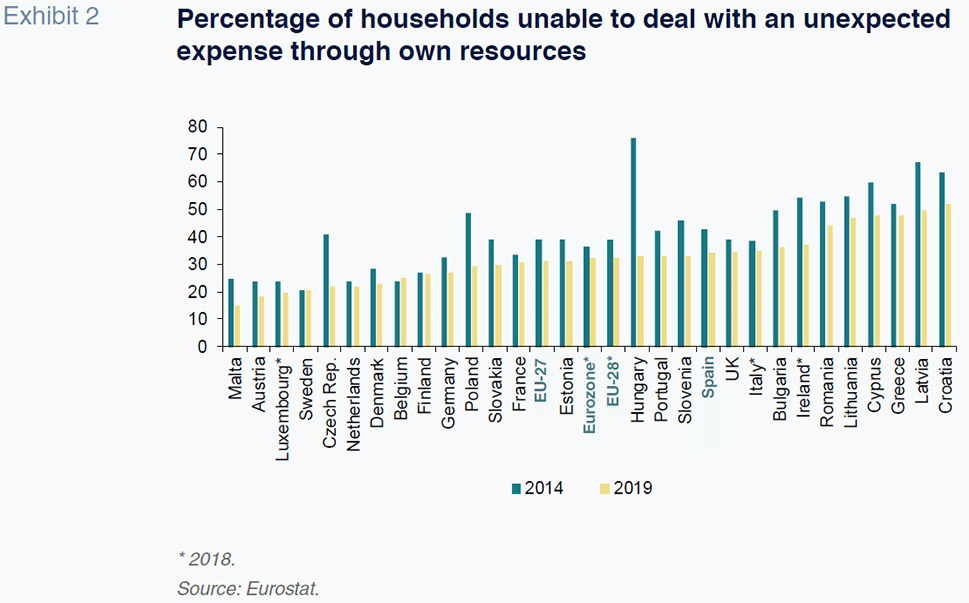

Eurostat provides the same information as the INE for the EU-27 member states. [1] The comparison shows that in 2019, the percentage of Spanish households that would be unable to deal with an unexpected expense was 2.5 percentage points higher than the EU-27 average (33.9% vs. 31.4%). Compared with the main EU economies, Spain’s households fare better than those in Italy (35.1%, 2018 figure) but are worse off than those of France (30.6%) and Germany (27%). The biggest gaps with the EU average were observed in 2014 and 2018 (3.7 percentage points more).

Economic resilience and vulnerable groups

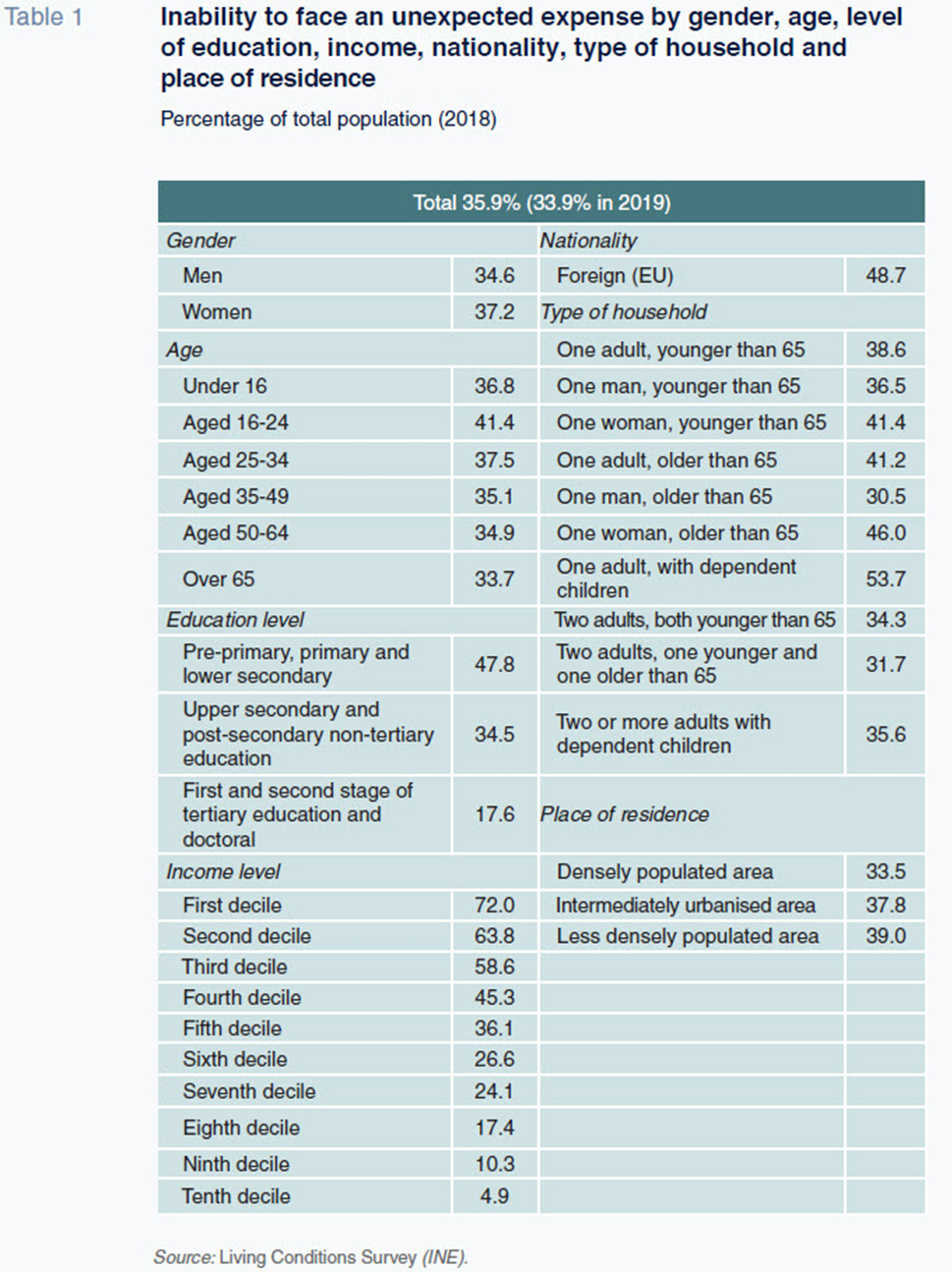

Depending on the characteristics of the individuals surveyed, the biggest determining factor in the ability to face an unexpected expense stems, logically, from income levels. If we order all Spanish households by income, within the third lowest-income tercile, at least 58.6% would be unable able to deal with an unexpected expense; that figure rises to 63.8% and 72.0% for the second and first (lowest) deciles.

The ability to face an unexpected expense also varies considerably by education levels, with higher levels of education correlated with higher levels of financial resilience. Among those with a lower secondary education, 47.8% of those surveyed would be unable to deal with an unexpected expense. In contrast, for those with higher levels of education, that percentage falls by almost two-thirds (to 17.6%).

By type of household, the most economically vulnerable group is that of one adult with dependent children, for whom 53.7% would be unable to face such an expense. Households made up of one woman of over 65 living alone are also vulnerable (46%).

The breakdown by age of those polled does not reveal significant differences, although those aged between 16 and 24 are more vulnerable. Lastly, neither gender nor place of residence (rural or urban area) are significant in explaining the differences in household economic resilience.

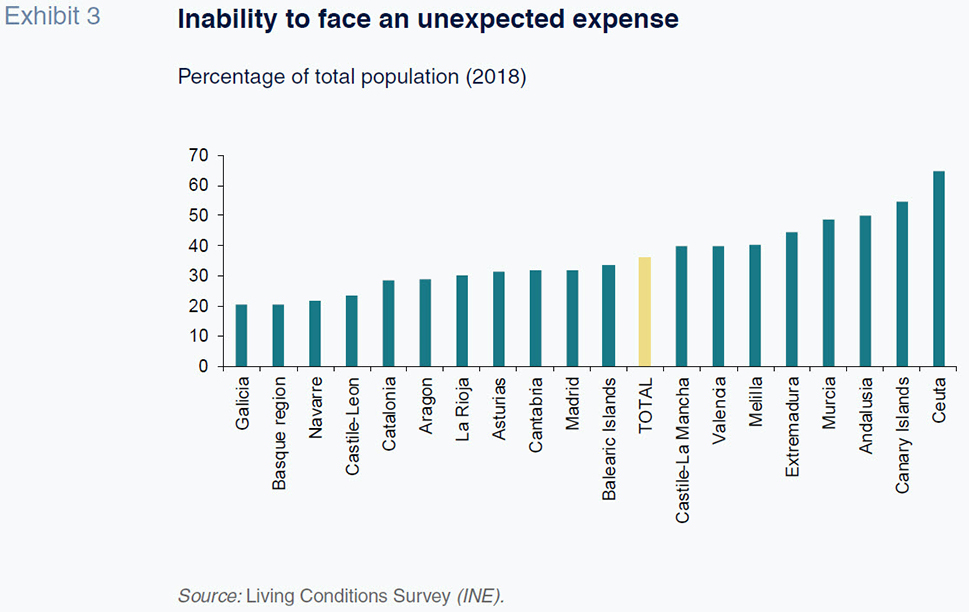

The ability to face an unexpected expense varies widely from one region to another, from a low of 20.3% in Galicia to nearly triple that amount —64.6%— in Ceuta. At the upper end of the spectrum it is also worth highlighting the vulnerability of the Canary Islands (54.7%), a region hit particularly hard by the pandemic on account of its high exposure to tourism, as well as Andalusia (50%). At the other end of the spectrum, the Basque region, Navarre and Castile-Leon also present percentages of under 25%.

Looking at the trend in the percentages since the national average peaked in 2014, the surprising increase in certain regions during a period of clear-cut recovery —Aragon, Asturias, Cantabria and La Rioja in particular— is of concern. Conversely, in Catalonia, Melilla and Galicia the percentages have fallen by over 10 percentage points.

The ability to deal with an unexpected expense is closely related with the risk of poverty or social exclusion. This is defined as a situation in which at least one of the following conditions is met: a) income per capita, net of social transfers, less than 60% of the national median; b) households with very low work intensity, i.e., adults (aged 18-59) work 20% or less of their total work potential; and, c) deprived persons experiencing at least four out of nine deprivation items, i.e., cannot afford: to pay rent or utility bills; keep the home adequately warm; face unexpected expenses; eat meat, fish or a protein equivalent every second day; take a week’s holiday away from home; a car; a washing machine; a colour TV; or a telephone. Note that the inability to face an unexpected expense is just one of the indicators of the risk of poverty or social exclusion.

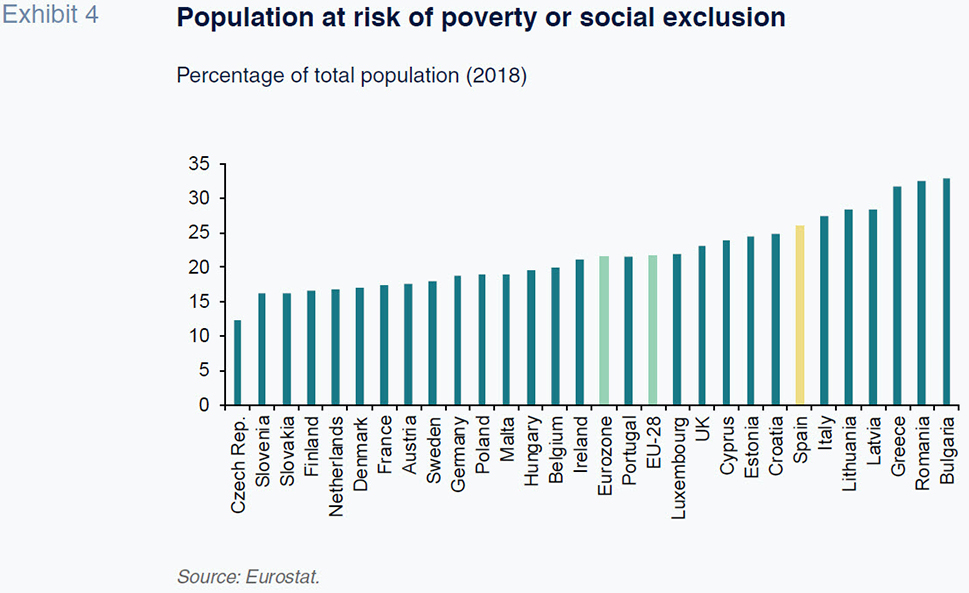

According to the 2019 data, 25.3% of the Spanish population is at risk of poverty or social exclusion. By comparison with Europe, that percentage is 4.3 and 4.5 percentage points above the EU-28 and eurozone averages, respectively (using 2018 data, the latest available). In absolute terms, that is equivalent to 4.5 million households in Spain with 12 million inhabitants. These data imply a huge economic policy challenge, as it means that before the COVID-19 crisis even erupted, millions of Spaniards were already in a position of tremendous vulnerability.

Using the 2019 numbers, the regional dispersion is again wide, ranging from 11.7% in Navarre to 37.7% in Extremadura (45.9% in Ceuta). Eight Spanish regions present a higher percentage of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion than the EU-28 average.

Implications

The high percentage of Spaniards at risk of poverty or social exclusion and of people unable to deal with an unexpected expense of a relatively small amount (700 euros) means that large swaths of the population are tremendously vulnerable, most notably the unemployed, as joblessness is the main factor behind poverty risk. Indeed, the percentage of unemployed people at risk of poverty or social exclusion (56.9%) is 3.7 times that of those in work (15.3%). Moreover, another 7.4% of the population has a very hard time making ends meet every month, increasing the percentage of people facing financial difficulties to 27.3%. The percentage of jobseekers who find it hard to make ends meet rises to 21.8%, which is triple the overall average.

Given that unemployment is the key determinant of poverty, in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, it is important to extend the furlough scheme in those sectors in which the crisis is expected to be deeper and more protracted, such as tourism-related activities. Their extension is of vital importance considering the fact that social transfers (such as the furlough scheme) have mitigated the increase in inequality in income distribution. The evidence provided by Aspachs et al. (2020) shows that without those transfers, inequality would have risen sharply, as job destruction and wage cuts have disproportionately affected lower wage earners.

All available estimates point to a sharp and unavoidable increase despite the battery of measures implemented to cushion the economic fallout from the health crisis. Specifically, in its worst-case scenario, the Bank of Spain puts unemployment at 22.1% in 2021. It is therefore important to roll out targeted measures for the most vulnerable groups of society (namely those already at risk of poverty or social exclusion before the pandemic), such as the recently approved minimum income scheme.

Policymakers should pay special attention to young people to ensure that the crisis does not further undermine their job prospects and chances of earning a decent living. As we saw earlier, those aged between 16 and 24 present the highest percentage of an inability to deal with an unexpected expense (41.4%, 5.5 percentage points above the average for all age groups). The same holds for the ‘at risk of poverty or social exclusion’ indicator, which affects 31.7% of those aged between 16 and 29, 6.4 percentage points above the overall average.

This worrying situation is exacerbated by unemployment concerns. Not only is youth unemployment high in absolute terms, it has risen disproportionately since the onset of COVID-19. Although the unemployment figures should be interpreted with caution on account of the furlough scheme, between the end of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020 (the latest figure available at the time of writing this article), the unemployment rate of those aged under 25 had increased by 9.1 percentage points, compared to an increase of 1.2 percentage points for those aged over 25. As a result, the unemployment rate in the youngest age bracket has climbed to 39.6%, which is nearly triple the level observed in the next-youngest category (13.8%).

Consequently, the expression of solidarity needed to transition out of this crisis requires intergenerational generosity, from pensioners to youths. It would be very unfair if future generations —today’s youth— have to bear the increased burden of the debt that is issued to surmount the COVID-19 crisis. Thus, any package of measures rolled out to combat the crisis should prioritise youth job creation.

Notes

The amount established by each country (700 euros in Spain) for this indicator depends on the risk of poverty threshold per equivalent unit of consumption. It is therefore independent of a household’s size or structure.

References

ASPACHS, O., DURANTE, R., GARCÍA-MONTALVO, J., GRAZIANO, A., MESTRES, J. and REYNAL-QUEROL, M. (2020). Measuring income inequality and the impact of the welfare state during COVID-19: Evidence from bank data, VOXEU/CEPR, August 6th.

Joaquín Maudos. Professor of Economic Analysis at the University of Valencia, Deputy Director of Research at Ivie and collaborator with CUNEF