Impact of COVID-19 on Spain’s deficit and debt: Greater than initially expected

COVID-19 has resulted in a series of downward revisions of Spain’s economic forecasts, with current projections indicating a sharp rise in both the government deficit and stock of debt. As a result, it could take Spain until 2050 to bring public debt below 60% of GDP.

Abstract: COVID-19 has upended the government’s spring forecasts, which included a projected deficit of 10.3% of GDP in 2020. The sharp economic contraction sustained in the second quarter, coupled with the spike in social spending and the automatic drop in tax revenue, have placed significant burdens on the government’s finances and necessitated several downward revisions of spring forecasts. The most recent forecasts available, which date to September, fall within a very wide band, ranging from a contraction of 9% to one of 14%. Although Spain is set to receive the equivalent of 11% of its GDP from the EU recovery fund, the first round of transfers in 1Q2021 will support structural reforms instead of stimulating the economy in the short-term. Worryingly, the AIReF estimates that it could take Spain until at least 2050 to bring public debt below 60% of GDP. In order to improve its debt sustainability outlook, Spain will need to enact necessary reforms, such as lowering corporate and personal income tax rates, as well as recalibrating the tax basket to lean more heavily on consumption. The overarching goal must be to preserve the economy’s productive fabric and lock in greater tax revenue over the long-term.

The first key factor: The tremendous contraction in 2020 GDP

The pandemic triggered by COVID-19 has essentially eliminated the prospect of economic growth in Spain in 2020.

[1] One of the most severe consequences of the subsequent contraction is the significant financing gap it is leaving in the public accounts. This situation will require at least the next two decades’ worth of substantial efforts to bring the deficit and public debt back to 2019 levels.

[2] As a result of the global and health-related exogenous shock, Spanish gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 5.1% in the first quarter of 2020 (INE, 2020a). The second-quarter contraction was far more severe, at 18.3% (INE, 2020a),

[3] due to the paralysis of all non-essential activities between March 30

th and April 9

th.

[4] There is no record in the quarterly series, which date back to the 1970s, of GDP contraction as devastating as that observed in the first half of 2020. By way of comparison, during the Great Recession of 2008, Spanish GDP contracted by 3% in the first quarter of 2009.

The indicators available to date suggest that economic activity began to recover in Spain in May. In July, however, the OECD observed signs of a further slowdown which should be confirmed in the weeks to come. Tourism, a key sector for the Spanish economy,

[5] is facing a particularly harsh scenario in the wake of the new rise in COVID-19 cases right in the middle of the summer. Since the end of July, most European countries, including the UK, Germany and France, have introduced restrictions on travel to Spain.

[6] It is estimated that between 2 and 2.5 percentage points of GDP contraction in 2020 will be attributable to tourism (García and Andreu, 2020). To illustrate the impact, in June 2019, Spain welcomed a total of 8.8 million foreign tourists, a figure that fell to 0.2 million in June of this year (INE, 2020c).

[7]

The high level of uncertainty has led to a constant downward revision of the growth estimates for 2020 since the middle of April. The most recent forecasts available, which date to September, fall within a very wide band, ranging from a contraction of 9% to 14%. That five percentage point difference echoes doubts about the speed with which the Spanish economy will recover during the second half of 2020 (AIReF, 2020a; Bank of Spain, 2020a; BBVA-Research, 2020a; Funcas, 2020a and 2020b; OECD, 2020a; European Commission, 2020; IMF, 2020). On average, however, using the consensus forecast gleaned from the Funcas Panel, the Spanish economy is expected to contract by 12.0% this year (Funcas, 2020a). The forecasts for 2021 point to sharp growth which will offset, albeit only partially, the 2020 contraction. For 2021 the growth forecasts range between 5.7% and 10.1%, with the Funcas consensus forecast indicating growth of 7.3% (Funcas, 2020a). In short, the estimated growth forecast for the Spanish economy in 2021 will be equivalent to two-thirds of the contraction anticipated in 2020.

The above estimates do not take into account the aid Spain will receive from the recovery package approved by the European Council on July 21st. Specifically, Spain will receive a sum equivalent to 11% of its GDP, 72 billion euros of which will come in the form of direct aid for stimulating the economy via investments targeted at the twin green and digital transition objectives, including sustainable mobility. Those funds, 10% of which may be received starting in the first quarter of 2021, could boost growth above current forecasts. Those initial funds, however, in addition to being limited in scale, will be provided more to support structural reforms than to stimulate the economy in the short-term (Bandrés et al., 2020).

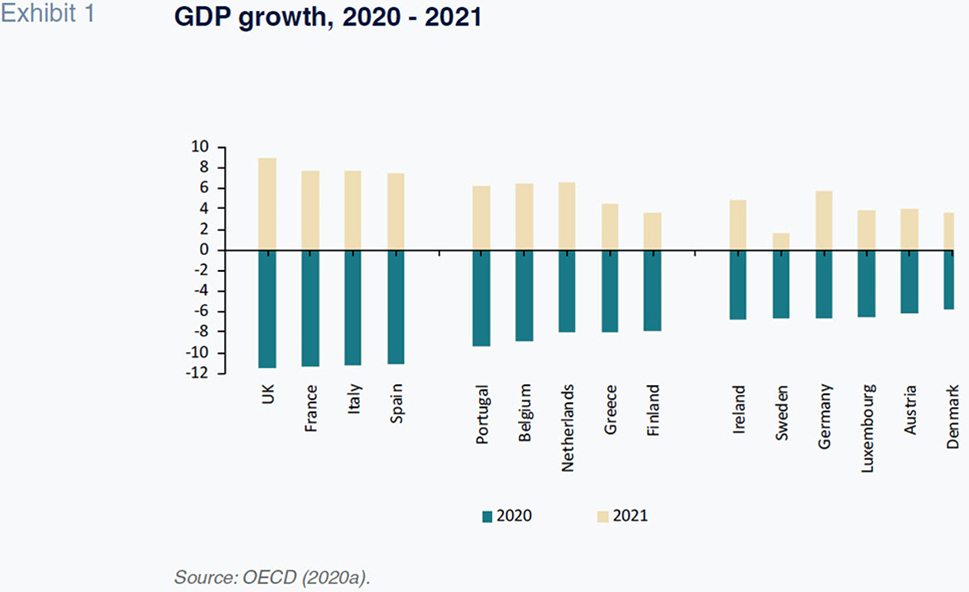

In comparative terms, international organisations, such as the OECD (2020a) and the IMF (2020), warn that Spain will be one of the economies hardest hit by the pandemic in terms of growth, but also in terms of deficit and debt. For illustrative purposes, Exhibit 1 compares the estimated impact on GDP for the EU-15 member states (OECD, 2020a). Despite considerable dispersion, it is possible to group the countries into four categories in terms of the size of the expected contraction. The first group is made up of the UK (-11.5%), France (-11.38%), Italy (-11.28%) and Spain (-11.14%), where the forecast GDP contractions are all very close to 11%. The second group is populated by Portugal, Belgium, the Netherlands, Greece and Finland, where the contraction is estimated at between 8% and 9%. Lastly, the third set of economies, which includes Ireland, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Austria and Luxembourg, is expected to see GDP contractions of between 6% and 7%. The countries in the first group are expected to register stronger growth of between 7% and 9% in 2021. A common trait shared by all the EU-15 member states is that the growth forecast for 2021 will not be sufficient to fully offset the contraction anticipated in 2020.

[8]

Updated deficit forecasts for 2020

As it is required to do every year, at the end of April, the Spanish government sent the European Commission (EC) an updated version of its Stability Programme for 2019-2022 (hereinafter, the SPU-2020). That document contains, among other information, the government’s growth forecasts for 2020 and 2021 and its deficit and debt forecasts for 2020. The macroeconomic forecasts contained in the SPU-2020 are, on the whole, very detailed in terms of both the methodology used and the forecasts themselves. In contrast, the section devoted to the budget projections, particularly the coverage of the public revenue forecasts, contains scant and vague information about the methodology and resulting estimates (Sanz and Romero, 2020).

The SPU-2020 was compiled under the ‘new European fiscal framework’ in which the budget stability rules have been put on hold following activation of the general escape clause at the end of March.

[9] This new framework, which is wholly exceptional, has had direct effects on the deficit and debt forecasts set down in the SPU-2020, most notably in the following ways:

- Suspension of the deficit and debt limits gives the EU member states ‘free rein’ to step up public spending to support their health systems and their economies. Spain has been one of the countries to do so. BBVA Research (2020b) estimates that public spending in Spain could increase by between 10 and 11 percentage points to reach 52% of GDP in 2020. However, the stimulus measures in Spain have been handicapped volume-wise by the weak health of its public accounts: Spain recorded a deficit of 2.83% and public borrowing ratio of 95.5% in 2019. One of the direct consequences of that situation has been relatively less support for Spanish companies in the form of income and social security tax deferrals relative to neighbouring economies (Romero-Jordán and Sanz-Sanz, 2020).

- The escape clause has also had the effect of suspending the 7.8 billion euros of budget cuts the EC demanded of Spain in 2019 to ensure delivery of the debt forecasts contemplated in the Stability Programme for that year (SPU-2019) (Romero-Jordán and Sanz-Sanz, 2019). Had the COVID-19 crisis not emerged, that adjustment alone would have shaved 0.7 percentage points off the public deficit in 2020. Looking back, it should be said that the EC’s doubts about the likelihood of Spain meeting the debt levels committed to in the SPU-2019 were reasonable in light of the systematic push-back of delivery of the balanced budget target observed over the last five years. The years of growth between 2015 and 2019 constitute a missed opportunity for balancing the budget. Indeed, a decisive commitment to eliminating the structural deficit would have put Spain in a far more favourable position for tackling the harsh economic fallout from the pandemic.

The Spanish government forecasts a deficit of 10.3% of GDP, or 115.3 billion euros, in the SPU-2020. The report issued by the AIReF (2020b) mid-May put the estimated deficit at a higher level, specifically within a range of 10.9% in the best-case scenario and 13.8% in the worst-case scenario. According to the independent fiscal institution’s estimates, Spain will report a deficit of between approximately 122 and 155 billion euros in 2020, i.e., between 7 and 40 billion euros more than the government’s forecasts. The worst-case scenario modelled by the AIReF assumes a deterioration of the epidemiological situation of a magnitude that once again affects the economy’s ability to produce, forcing another one-month lockdown during the autumn. Despite the significant uncertainty surrounding the directions both the pandemic and the economy are headed, it is worth highlighting the following downside risks vis-à-vis the second half of the year:

- The chances of a new lockdown, at least in the major cities or large geographic regions, should not be ruled out in light of the surge in cases since June. At present there are nearly 1,200 active clusters in Spain and they are affecting some of the largest cities, including Zaragoza, Barcelona and Madrid. [10] Indeed, the Basque region declared a health emergency in August as a result of the sharp increase in its caseload. [11]

- The ‘second wave’ means that some key sectors of the Spanish economy are suffering bigger than expected contractions, the tourism sector being of greatest concern in this respect. [12] CaixaBank Research (2020) is forecasting a 50% and 30% drop in spending by foreign and domestic tourists, respectively.

- The data on daily card payments and cash withdrawals from ATMs suggest that consumer spending stagnated towards the end of July, which is when case numbers began to surge (BBVA Research, 2020c). In a similar vein, the OECD (2020b) has warned of signs of an economic slowdown in Spain in July, in contrast to the trends observed in neighbouring countries.

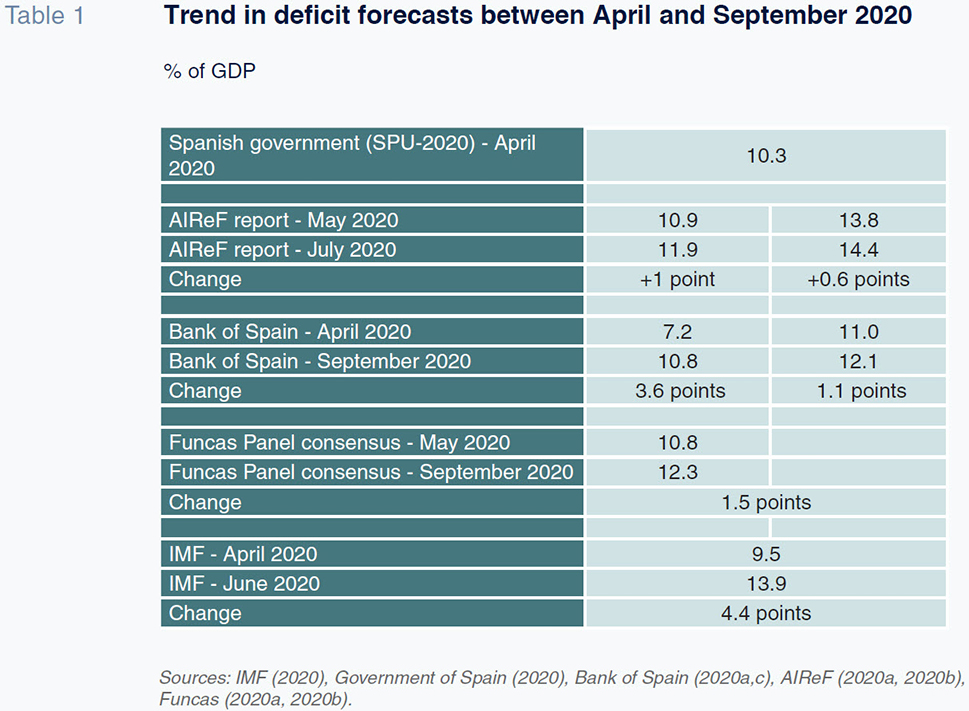

Against that backdrop, the latest deficit forecast updates are more pessimistic than those made in April and May. Table 1 provides a comparison of the trend in the estimates published by the AIReF, Bank of Spain, Funcas Panel and the IMF between those two periods. The estimates are not comparable in general as the Bank of Spain and AIReF provide outcomes for two alternative scenarios, whereas the Funcas consensus forecasts and the IMF publish baseline forecasts. Despite those caveats, Table 1 allows us to draw the following conclusions:

- In the best-case scenario modelled by the Bank of Spain and AIReF, the deficit estimate widened from a range of between 7.2% and 10.9%, respectively, in May to between 10.8% and 11.9%, respectively by July-September, i.e., the forecast deficit increased by 3.6 percentage points of GDP for the Bank of Spain and 1 percentage points of GDP for the AIReF within that short timeframe. In their worst-case scenario forecasts, the deficit widens by a further 1.1 percentage points for the Bank of Spain and by 0.6 percentage points for the AIReF, reaching 12.1% and 14.4%, respectively.

- The detailed update presented by the AIReF in July reveals that its estimate for the 2020 deficit increased by between 0.6 and 1.0 percentage points of GDP between May and July. That update implies an additional increase with respect to the official government forecasts of between 6.7 and 11.2 billion euros. As a result, following the July update, the AIReF puts the 2020 deficit at between 133 and 161 billion euros.

- The most recent estimates gleaned from the Funcas Panel similarly reveal a 1.5 percentage point deterioration in the 2020 deficit forecast, to 12.3%. Lastly, the IMF increased its deficit forecast by 4.4 percentage points to 13.9% in its last update.

Three factors explain the deterioration in the deficit forecasts. (i) The extraordinary slump in economic activity during the second quarter of the year; (ii) The sharp increase in public spending, particularly the furlough schemes,

[13] health spending and the new minimum income scheme (the latter not contemplated in the SPU-2020); and, (iii) Lastly, the adverse trend in revenue collection.

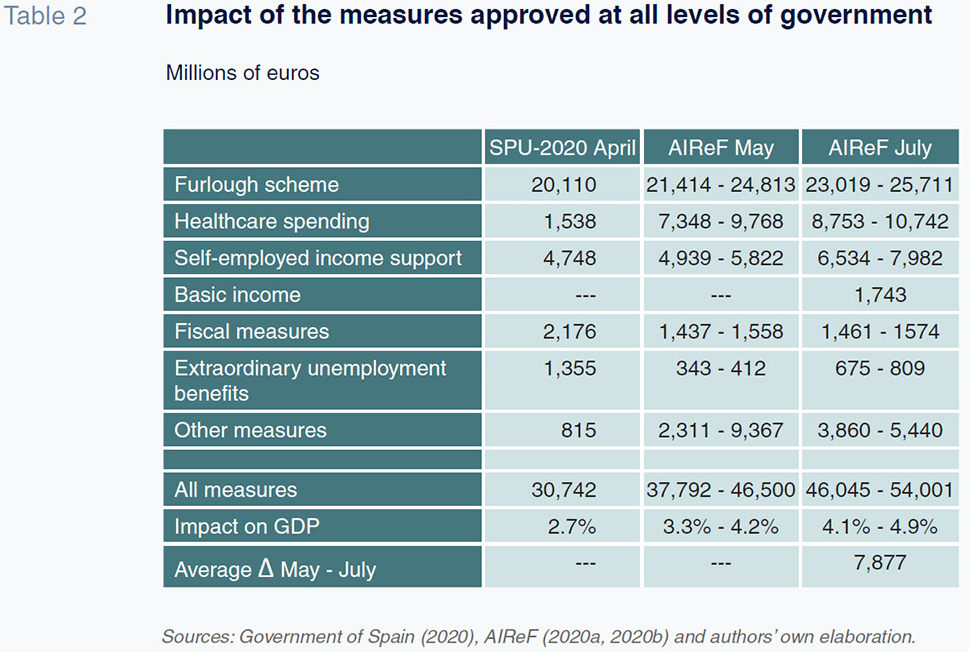

Table 2 shows the impact of the measures, which are concentrated on the spending side, approved by the various levels of government since April. The first of the three columns reflects the government’s estimates as of April. The next two columns present the estimates made by the AIReF in May and in July. The table shows how the government’s forecasts put the impact of the measures at 30.74 billion euros. Of the total, 65.4% corresponds to the furlough scheme, 15.4% to the income support scheme for self-employed professionals and just 5.0% to healthcare spending. The number of employees under the furlough scheme peaked at 3.4 million between the end of April and beginning of May and has trended down since then to 0.96 million as of mid-August.

[14] The scheme was due to end on September 30

th, but has been extend until the end of the year. To finance this programme, the government has applied for 20 billion euros from the European Commission’s SURE scheme for tackling unemployment.

As shown in Table 2, the government expects the measures rolled out to generate a level of expenditure equivalent to 2.7% of GDP. In its May estimates, the AIReF put that figure at a higher 3.3% to 4.2% of GDP, i.e., between 7 and 15.8 billion euros more than the government’s forecasts. In its July update, the AIReF raised those forecasts again, to between 4.1% and 4.9% of GDP. That 0.8 percentage point increase is equivalent to an additional 8 billion-euro deficit with respect to the government’s forecasts. Of that additional expenditure, 2.18 billion euros is attributable to the income support scheme for the self-employed, 1.6 billion euros to the furlough scheme, 1.5 billion euros to healthcare spending and 1.74 billion euros to the minimum income scheme.

It is likely that the cost of those measures will continue to increase over the coming months as a result of the extension of the furlough scheme beyond September, introduction of a new exceptional benefit for job-seekers whose entitlement to jobless claims has run out,

[15] growth in health spending as a result of the fresh outbreaks and the hiring of more teachers and purchase of materials to reopen schools across the country. Elsewhere, the drop in public revenue will contribute to the burgeoning deficit in 2020. The data published by the Spanish Tax Authority show that net tax revenue declined by 11.04% (equivalent to 9.66 billion euros) between January and July 2020 (AEAT, 2020). Of that total, 3.95 billion euros stems from lower VAT revenue, 3.92 billion to lower corporate income tax receipts, 1.34 billion euros to duties as a whole and 176 million to personal income tax. What that means is that the drop in VAT and corporate income tax accounts for 81.4% of the decline in tax revenue. Social security tax receipts, meanwhile, decreased by 1.23%, or 764 million euros, between January and May (IGAE, 2020).

Public debt 2020: A quantitative leap

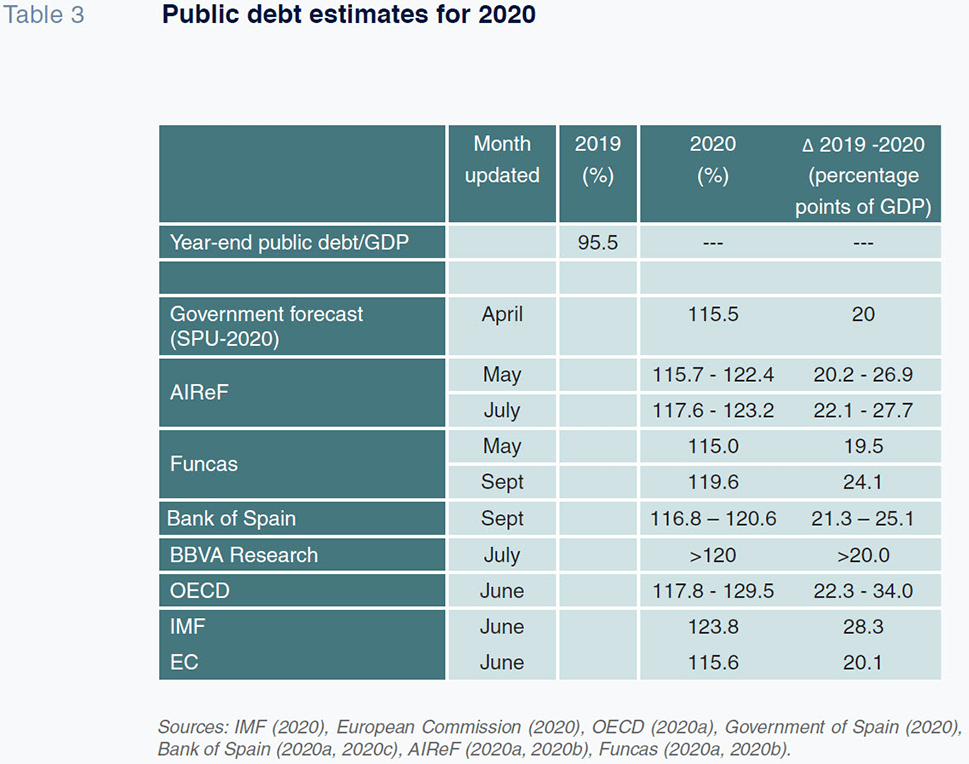

According to the SPU-2020, in 2020 public debt will rise by 20 percentage points to 115.5% of GDP, from 95.5% in 2019, or an increase of 103.8 billion euros, from 1.19 trillion euros in 2019 to 1.29 trillion euros this year. For comparative purposes, Table 3 provides the current estimates for public debt in 2020. The information presented in the table shows that the 20 percentage point increase in borrowings forecast by the government is close to the increase estimated by the AIReF, Bank of Spain and OECD in the scenario that assumes a swift economic recovery. In the event of a slower recovery, the increase in debt would be 25.1 percentage points according to the Bank of Spain, 27.7 percentage points in the opinion of AIReF and 34.0 percentage points judging by the OECD’s estimates. In short, according to these three organisations, Spain’s public borrowings could increase by between 146.3 and 260.5 billion euros in 2020. An increase of that magnitude would drive Spain’s public debt from 1.19 trillion euros in 2019 to between 1.34 and 1.45 trillion euros in 2020.

The most recent Bank of Spain data on the stock of debt confirm that the increase will significantly surpass the government’s SPU-2020 estimates. As of June 2020, the stock of public debt in Spain stood at 1.29 trillion euros, which is already very close to the level estimated by the government for the end of 2020. That means that in just six months, Spain’s public debt increased by 101 billion euros, compared to the government’s estimate of 103.8 billion euros for the entire year.

[16] Of that increase, 87% was concentrated between March and June, when public debt increased at a monthly average of 22 billion euros. If that rate were to continue, the growth in the stock of public debt would end the year at close to 230 billion euros. In sum, the trend observed since the start of the pandemic makes it likely that the stock of Spanish debt could reach 1.4 trillion euros by the end of 2020.

This will be the second time in a little over a decade that the level of Spanish public debt has experienced a notable jump. The financial crisis of 2008 drove an increase in public debt of 65 percentage points in just seven years. Specifically, Spain went from having one of the lowest public debt ratios in the EU –35.8% of GDP in 2007– to one of the highest - 100.7% in 2014. As a result of the financial crisis of 2008 and the more recent crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, Spain’s public debt will have increased by over 80 percentage points of equivalent GDP, or approximately 0.9 trillion euros, between 2008 and 2020. Between 2014 and 2019, years of vigorous growth, public debt declined by 5.2 percentage points of GDP. However, that reduction was attributable exclusively to the denominator (GDP) effect, Namely, outstanding liabilities increased by 14.4% during that period, while GDP registered cumulative growth of 20.6% (Bank of Spain, 2020b). In 2020, Spain’s public debt will jump up another notch, climbing at least 25 percentage points of GDP.

As a result, from 2020 Spain will face a debt sustainability challenge. Apart from the financing issues that could emerge in the medium-term, the high level of debt will imply significant restrictions in the event of new unexpected exogenous shocks that require counter-cyclical policies (Burriel et al., 2020). As a result, it is necessary to plan for a long-term fiscal consolidation process designed to bring the borrowing ratio back down below 60% of GDP. The simulations run by the AIReF (2020b) show that it will take at least two decades to bring Spain’s debt back to pre-COVID levels, assuming that the deficit is reined in by 0.5 percentage points every year until a primary surplus is reached. Based on that same deficit reduction path, it could take until at least 2050 to bring public debt below 60% of GDP, according to the AIReF.

Spain will not embark on that fiscal consolidation process until at least 2022 as the European authorities have decided to keep the escape clause activated until at least 2021. Accordingly, the earliest budget framed by orthodox Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) rules will be that of 2022. Nevertheless, the government needs to start planning immediately for the fiscal consolidation effort that will become Spain’s destiny in the years to come. That fiscal austerity will need to focus initially on the spending side of the equation in order to eliminate all superfluous and unnecessary current expenditure. It will also be necessary to review the major investment projects, such as the high-speed rail network, which will be rendered non-viable by the dramatic increase in public debt. Once spending has been pared back, the tax system needs to be reformed to prevent even greater damage to the productive structure. Here it is important to stress that without economic growth there can be no recovery; hence the need to focus on containing the exacerbated economic contraction in the first half of 2020 and to pave the way for a period of sustained growth. To that end, during the initial stages of the recovery it would be advisable, as other European Union member states have already done, to permanently reduce the average and marginal tax burden of the taxes that impact economic growth the most: corporate and personal income tax. Although tax cuts of that nature would erode tax revenue —and the public finances— in the short-term, they are the most effective means of preserving the economy’s productive fabric and would lock in greater tax revenue over the long-run. Failing to do so would be to risk irreversible damage to both the productive fabric, and the country’s revenue base by extension, potentially delaying or even thwarting economic recovery for a long period of time. Naturally, that is not to say that Spain should renounce the tax collection measures that the pandemic has made inevitable. Rather, the collection effort needs to focus on consumption taxes - VAT and excise duties, those taxes with strong revenue potential that weigh least heavily on growth. Note, lastly, that Spain has lagged in the recalibration of the tax basket to lean more heavily towards consumption, as most European countries initiated these reforms years ago.

Notes

The government’s estimates as of February 2019 called for GDP growth of 1.6%.

As in other European Union economies, such as France and Italy, in March, the Spanish government opted to lock down the entire population in order to curb the spread of the pandemic and prevent the collapse of the health system. To that end it declared a state of emergency, which remained in place for over three months, from March 14th to June 21st. The government began to ease lockdown restrictions from May 1st.

Seasonally and working-day adjusted.

Each week of lockdown detracted from GDP an estimated 0.8 percentage points; that impact rises to 1.5 percentage points during the period of harsher restrictions on all non-essential activities (AIReF, 2020).

Accounts for 12.3% of Spanish GDP (INE, 2020b).

For example, on July 26th, the British government imposed a 14-day quarantine on travellers arriving from Spain. To illustrate the magnitude of the potential impact, note that British and French tourists account for around 41% of total visitors to Spain annually.

In the case of British tourists, one of the most important sources of visitors to Spain along with the Germans and French, the number of arrivals fell from 2 million to close to 8,500 people between June 2019 and June 2020.

The country with the most balanced forecasts is Germany, which is expected to contract by 6.60% in 2020 and grow by 5.77% in 2021 (OECD, 2020a).

Approved at an extraordinary meeting of the Eurogroup on March 26th, 2020.

Certain small areas of Lerida, Lugo, Valladolid and Burgos were locked down for a fortnight in July-August. Other larger cities, such as Zaragoza, have asked their citizens to shelter in place voluntarily.

Indeed, the regions more dependent on tourism, such as the Balearic Islands, Valencia, Catalonia and the Canary Islands, suffered relatively higher GDP contraction in the second quarter of the year (AIReF, 2020c).

The first round of the furlough scheme, or ERTEs for their acronym in Spanish, was approved in March with a view to safeguarding jobs. Under the scheme, employers can suspend employment contracts as a result of the effects of the pandemic. In essence, the affected employees receive unemployment benefits even if they have not been paying into their social security for the required minimum period of time. Employers, meanwhile, obtain full or partial exemption from their social security payments, depending on the number of people they employ.

References

AEAT. (2020). Monthly tax collection reports. Retrievable: https://www.agenciatributaria.es/AEAT.internet/datosabiertos/catalogo/hacienda/ Informe_mensual_de_Recaudacion_Tributaria.shtml AIReF. (2020a).

Report on the 2020-2021 Stability Programme Update. Report 2/20. Retrievable: h

ttps://www.airef.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/INFORMES/AIReF-Informe-APE-2020-2021_EN_FINAL.pdf —. (2020b).

Report on 2020 Budgetary Execution, Public Debt and Expenditure Rule. Report 3/20. Retrievable:

https://www.airef.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/INFORMEJULIO-EN/Informe-de-Ejecuci%C3%B3n-Presupuestaria-Deuda-P%C3%BAblica-y-Regla-de-Gasto-2020_DAE_DAP.pdf —. (2020c).

GDP estimates by region. Retrievable:

https://www.airef.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/METCAP/PIB_CCAA_2020-T2-WEB-31-julio-2020.pdf BANK OF SPAIN. (2020a).

Macroeconomic projections for the Spanish economy (2018-2020): The Banco de España’s contribution to the Eurosystem’s June 2020 joint forecasting exercise. Retrievable:

https://www.bde.es/bde/en/areas/analisis-economi/analisis-economi/proyecciones-mac/Proyecciones_macroeconomicas.html —. (2020b).

Liabilities outstanding and debt according to the excessive deficit procedure (EDP). Retrievable:

https://www.bde.es/webbde/en/estadis/infoest/temas/sb_deuaapp.html —. (2020c).

Escenarios macroeconómicos para la economía Española 2020-2022. Retrievable:

https://www.bde.es/bde/es/secciones/informes/boletines/relac/Boletin_Economic/Informes_de_proy/BANDRÉS, E., GADEA, L., SALAS, V. and SAURAS, Y. (2020). Spain and the European Recovery Plan.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 9, No. 4, July 2020. Retrievable:

https://www.sefoFuncas.com/Challenges-for-Spanish-industry-under-COVID-19-and-beyond/Spain-and-the-European-Recovery-PlanBBVA RESEARCH. (2020a).

Spain Economic Outlook. Third Quarter 2020. Retrievable:

https://www.bbvaresearch.com/en/publicaciones/spain-economic-outlook-third-quarter-2020/ —. (2020b).

Public expenditure during the crisis. Retrievable:

https://www.bbvaresearch.com/en/publicaciones/spain-public-expenditure-during-the-crisis/ —. (2020c).

Impact of COVID-19 on consumption in real time and high frequency: 30 July. Retrievable:

https://www.bbvaresearch.com/en/publicaciones/spain-impact-of-covid-19-on-consumption-in-real-time-and-high-frequency-30-july/ CAIXABANK RESEARCH. (2020).

La pérdida de actividad turística supone un duro golpe para la economía española [The loss of tourism activity comes as a sharp blow to the Spanish economy]. Retrievable:

https://www.caixabankresearch.com/es/analisis-sectorial/turismo/perdida-actividad-turistica-supone-duro-golpe-economia-espanola?index EUROPEAN COMMISSION. (2020).

European Economic Forecast, Summer 2020. Retrievable:

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/ip132_en.pdf FUNCAS. (2020a).

Spanish economic forecasts panel: September 2020. Retrievable:

www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/PP2009.pdf—. (2020b).

Spanish economic forecasts panel: May 2020. Retrievable:

https://www.sefofuncas.com/pdf/Panel9_3.pdfGARCÍA, G. and ANDREU, A. (2020). The blow to tourism and the recovery of the Spanish economy.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 9, No. 4, July 2020. Retrievable:

https://www.sefoFuncas.com/Challenges-for-Spanish-industry-under-COVID-19-and-beyond/The-blow-to-tourism-and-the-recovery-of-the-Spanish-economyGOVERNMENT OF SPAIN. (2020).

Stability Programme Update, 2020 - 2021. Retrievable:

https://www.hacienda.gob.es/CDI/Programas%20de%20Estabilidad/Programa_de_Estabilidad_2020-2021.pdf IGAE. (2020).

Non-financial operations by the Social Security Funds sub-sector. Retrievable:

https://www.igae.pap.hacienda.gob.es/sitios/igae/en-GB/Contabilidad/ContabilidadNacional/Publicaciones/Paginas/imnofinancierasSS.aspx IMF. (2020).

World Economic Outlook, June 2020. Retrievable:

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/06/24/WEOUpdateJune2020 INE. (2020a).

Quarterly Spanish National Accounts. Retrievable:

https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736164439&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735576581 —. (2020b).

Tourism Satellite Account of Spain. Retrievable:

https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/operacion.htm?c=estadistica_C&cid=1254736169169&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735576863—. (2020c).

Tourist Movement on Borders. Number of tourists by country of residence. Retrievable:

https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=10822 OECD. (2020a).

Economic Outlook, June. Retrievable:

http://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/june-2020/ —. (2020b).

Composite Leading Indicator, August. Retrievable:

https://www.oecd.org/sdd/leading-indicators/composite-leading-indicators-cli-oecd-august-2020.htm ROMERO-JORDÁN, D. and SANZ-SANZ, J. F. (2019). Zero-deficit target for 2022: Where is Spain coming from and where is it headed?

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 8, No. 5, September 2019. Retrievable:

https://www.sefoFuncas.com/The-ECBs-shift-back-towards-QE-Impact-on-the-banking-sector/Zero-deficit-target-for-2022-Where-is-Spain-coming-from-and-where-is-it-headed—. (2020). Spanish fiscal support measures: Boosting corporate liquidity in response to COVID-19.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 9, No. 3, March 2020. Retrievable:

https://www.sefoFuncas.com/Spain-and-the-EU-Assessment-of-policy-responses-to-COVID-19/Spanish-fiscal-support-measures-Boosting-corporate-liquidity-in-response-to-COVID-19SANZ-SANZ, J. F. and ROMERO-JORDÁN, D. (2020). El programa de estabilidad: un documento desigual [The Stability Programme. A Patchy Document]. Article published in the financial daily

Expansión on May 16

th, 2020.

Desiderio Romero-Jordán. King Juan Carlos University and the Funcas Public Finance Observatory (OFEP)

José Félix Sanz-Sanz. Madrid’s Complutense University and the Funcas Public Finance Observatory (OFEP)