Fiscal consolidation in Spain: State of play and outlook

The government continues on the path of fiscal consolidation, but there will likely be some deviation from 2015 targets, further complicating the outlook for 2016. Strategies to improve performance on deficit targets must give special consideration to the situation of the regions, including the debate over regional funding, as well as social security revenues.

Abstract: 2016 begins with one of the most uncertain political scenarios since the early eighties. On the positive side, the fact that the State Budget for 2016 was approved in December means that at least there is some degree of certainty on the budgetary front. However, several important challenges exist, particularly at the regional level and specifically over the non-compliance of targets. Different factors account for this problem, apart from the sharp reduction in regional deficit targets. There is also a great degree of variation across the regions, which should be taken into consideration at the time of analysing performance. In general terms, to ensure that the regional governments cease to be a source of instability and fiscal non-compliance, a multidimensional strategy will be required and should include trigger mechanisms in the event of non-compliance, which should be more automatic than those used in the past.

Fiscal consolidation in Spain: Recent developments

Consecutive deficits −unprecedented in Spain’s recent history– were the fundamental reason why Spain went from being a country with one of the lowest public-debt-to-GDP ratios in the European Union (EU-25), with a ratio of 40% in 2007, to having a ratio close to 100%. Thus, joining the group of most heavily indebted member states (Delgado, Gordo and Martí, 2015).

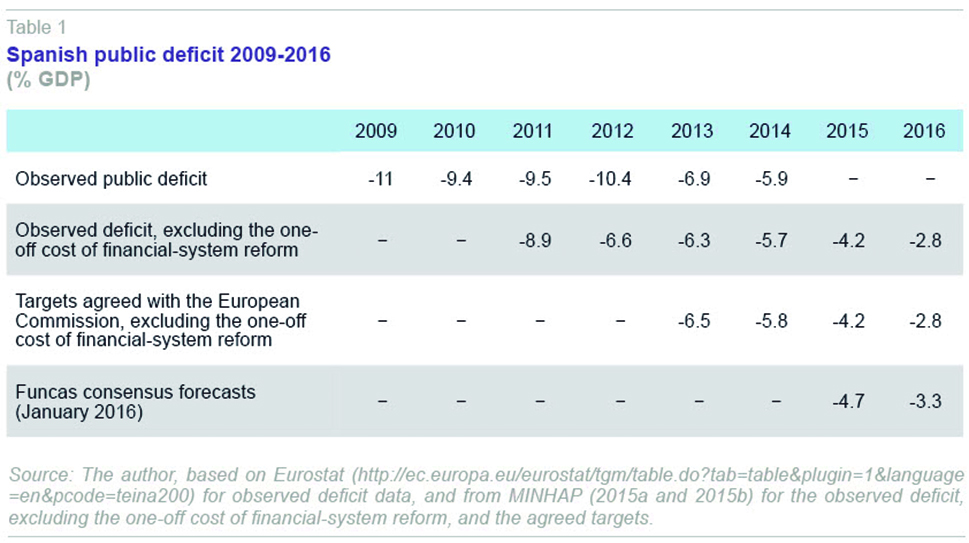

Nevertheless, Spain’s public accounts have improved significantly over the last three years, since the worrisome situation between 2009-2012, when Eurostat estimated Spain’s public deficit, including the one-off cost of the financial reform, at around -10% of GDP (Table 1).

There has been a clear fiscal consolidation effort, with the deficit falling from -6.9% in 2013 to -5.9% in 2014. Moreover, once the impact of financial restructuring is excluded, figures reflect: i) that consolidation really begun back in 2012; ii) that the real progress of 2013 and 2014 was less intense than the gross figures suggested; but also, iii) that fiscal consolidation targets were met in both years.

[1]

Figures are not yet available for actual budget execution, but various estimates suggest that the deficit target has been missed. In contrast to the -4.2% target set by the government, and agreed upon with the European Commission, Funcas’s consensus (January 2016) is -4.7%.

The fiscal slippage in 2015 is substantial and raises doubts over the feasibility of meeting the -2.8% target for 2016, since it raises the starting point, and necessitates more cuts to the government borrowing requirement. We will look at each of these issues in turn.

For several months, there have been doubts over compliance with the 2015 deficit target (Lago-Peñas, 2015). The Independent Fiscal Responsibility Authority’s July 2015 report (AIReF, 2015a) predicted that the fiscal targets adopted would be difficult to achieve. AIReF cited various reasons. First, a significant number of regional governments, including some of the territories with the greatest weight in the aggregate figures in population and budgetary terms, are set to miss their targets by a wide margin. This mismatch would be partly made up for by the local authorities, which are again on course to achieve an overall surplus. Second, because the social security system is not going to be able to meet its targets, and this time around, the central government will not provide the buffer generated by municipalities in the subnational treasuries’ aggregate. While it is true that economic activity picked up significantly in 2015, the positive effect of this on the budget’s automatic stabilisers (increased tax revenues, reduced spending on unemployment benefits, etc.) will be offset by other discretionary measures by the central government or contingencies that were not foreseen when the 2015 national budget was drafted. In particular, the Independent Fiscal Responsibility Authority, AIReF (2015b) estimates that the combined effect of the measures to support sub-national governments, bringing forward the income-tax reform planned for 2016 to July 2015, the final settlement of the financing of the autonomous regions for 2013, and a smaller than expected quota and financial compensation from the Basque Country, will reduce the central government’s revenues by around 0.5% of GDP.

At the time this article was written, the most recent data on budgetary execution for the general government as a whole in consolidated terms from September 2015 (MINHAP, 2015c) are in line with AIReF’s projections. The cumulative deficit in the first three quarters of the year was equivalent to -3.10% of GDP, a figure 0.48 points below that registered in 2014 (-3.58%). Data are available for the period to October (except for the local authorities, with a cumulative surplus of between three and four tenths of a point of GDP) and the figures are -3.42%, in 2015, and -3.93%, in 2014, respectively, which implies a reduction of 0.51 percentage points. Although the cut is substantial, if we extrapolate, the results will be insufficient to achieve the overall deficit reduction envisaged for 2015 as a whole compared to 2014 (-1.5% of GDP).

The problem in meeting the targets mainly lies at the autonomous regions and the social security system level. In the case of the former, because the one-percentage-point reduction in 2015 (from -1.7% to -0.7% of GDP) is not going to be met. In the first ten months of the year, the overall deficit reduction by these levels of government was one tenth of a point (-1.29% in 2014 vs. -1.17% in 2015).

The latest projection published by AIReF (2015b) estimates the deficit for the autonomous regions as a whole between -1.5% and -1.6% of GDP, very close to FEDEA’s estimate (2015), calculated on the basis of execution data for the first seven months of 2015, and which does not anticipate the year’s deficit for the autonomous regions as a whole dropping below -1.4%.

In the case of the social security system, the cumulative figures for the period to October show a deficit of -0.25%, compared with a deficit of -0.02% in the same period one year earlier. That is to say, it has deteriorated by almost a quarter of a percentage point. This is in sharp contrast with the Stability Programme’s projections (MINHAP, 2015a), which were for an improvement from -1.1%, in 2014, to -0.6%, in 2015.

The short-term challenges: Outlook for 2016

This year is going to be a complicated one on the budgetary front. The fact that the State Budget for 2016 (PGE-2016) was submitted and approved before the elections on the 20th of December 2015, is an element of certainty in the most uncertain political scenario since the early nineteen eighties.

Nevertheless, whatever happens in the next few weeks or months, the budget will be amended for two reasons. First, due to the new internal political balance, reflecting the need to accommodate a different, or more plural, ideological perspective than that allowed by the broad absolute majority enjoyed by the government until now. And second, because the European Commission is going to demand additional efforts to compensate for the mismatch that is going to take place in 2015, and which increases the demands for fiscal consolidation in 2016. Even if the favourable economic situation persists as projected, the PGE-2016 does not seem to be the ideal tool with which to achieve a deficit of -2.8% in 2016 if the starting point is a financing requirement in 2015 that is finally closer to -5% than to the target of -4.2%.

[2]

Combining both forces for change will not be easy. It may demand further spending cuts, which will fall on public services that are already under strain after several years of cumulative cutbacks. It may also mean renouncing tax cuts and changing the tax system so it provides more resources rather than less, as happened in 2015. Alternatively, it could require a blend of both these ingredients. This may entail a reversal of recent decisions or breaking electoral promises in order to ensure fiscal sustainability.

In short, this will mean unpopularity for a government that, unless the parties gravitate towards a strong and stable coalition, will have little electoral and parliamentary capital to spend. And all the foregoing will need to be done within a limited timeframe, which will be all the shorter if the process of reaching an agreement to form a government drags on into the year.

Challenges for the new legislative period

The fiscal consolidation scenario will not be completed in 2016. It will be necessary to continue cutting the public deficit to eliminate the structural component and bring down the public-debt-to-GDP ratio from its current level near 100% of GDP as quickly as possible. The Stability Programme, in fact, offers paths pursuing these objectives up until 2018. But these paths suffer from various limitations.

The first limitation is that they put almost all the weight on the expenditure side. Specifically, they aim to set tax collection at 38% of GDP and to cut the expenditure ratio to this level (MINHAP, 2015a). In a favourable economic scenario, this would mean practically stabilising total spending in current terms and moving further away from the EU-25 average in terms of public financial efforts in most spending areas, including education, health and social protection. But Spain is not particularly efficient at using public resources (Lago Peñas and Martínez-Vázquez, 2016), and, at least in theory, there is a broad offer of public services covering health and education provided by the public sector with little direct financial input from users, long-term care services, an unfunded pensions system, etc. It is not easy to provide such an extensive (high quality) offering of public services in a context of decreasing resources, following a series of cutbacks since the start of the decade, and without reforms increasing efficiency.

On the revenue side, a more ambitious approach to fiscal reform seems to be required, going beyond tax cuts and not imposing the restriction of maintaining tax collection as a given percentage of GDP. The Spanish tax system suffers from numerous shortcomings that undermine its efficiency, equity and revenue-raising capacity, as made clear by the report by the panel of experts (Comisión de Expertos, 2014) commissioned by the Finance Ministry.

At the same time, the regions’ failure to meet their targets needs to be addressed, having recurred in 2014 after two years (2012 and 2013) in which marked progress had been made and the problem seemed to have been solved.

However, before looking for solutions to fiscal issues, it is important to understand their causes. Three points need to be taken into account. First, the corrective effect of toughening up Spanish legislation on budgetary stability in the period 2011-2012 that seems to have worn off somewhat.

Perhaps as a result of the political cost of applying it strictly and on a lasting basis, the reality is that the existing legal options have not been exhausted, as they even include suspending regional self-governance. The solution would therefore not seem to be to simply implement another reform of the budgetary stability laws –although it would be prudent to review them in light of lessons learned to date– but rather to remove the control and penalty mechanisms that do not work in practice and make remaining mechanisms more automatic.

The second point to take into account is that the greater non-compliance by the regions since 2013 has more to do with the fact that the targets have been made harder to meet (from -1.5% in 2012 to -0.7 in 2015) than with an increase in the deficit itself. The deficit has been kept at around -1.5%, but it is proving more difficult to reduce it further. As the regions’ borrowing requirements converge to 0% in 2018 (-0.3% in 2016 and -0.1% in 2017), the gap between the reality and the target will likely widen further.

The final point to take into account is that there is a substantial degree of variation across autonomous regions. Some of them have systematically failed to meet their targets in recent years (these include the Basque Country, Navarre, Madrid, and Galicia) and others show substantial and reiterated upward deviations, which are accelerating the rate at which their public debt is increasing (Valencia and Catalonia). One part of this diversity has to do with the relative treatment that the regional financing system gives each region. At one end of the scale, the “foral” communities (i.e., Navarre and the Basque Country) have higher per capita funding than the rest, making adjustments easier and enabling them to run smaller deficits. At the other, the Community of Valencia has historically had a level of funding per inhabitant well below the average.

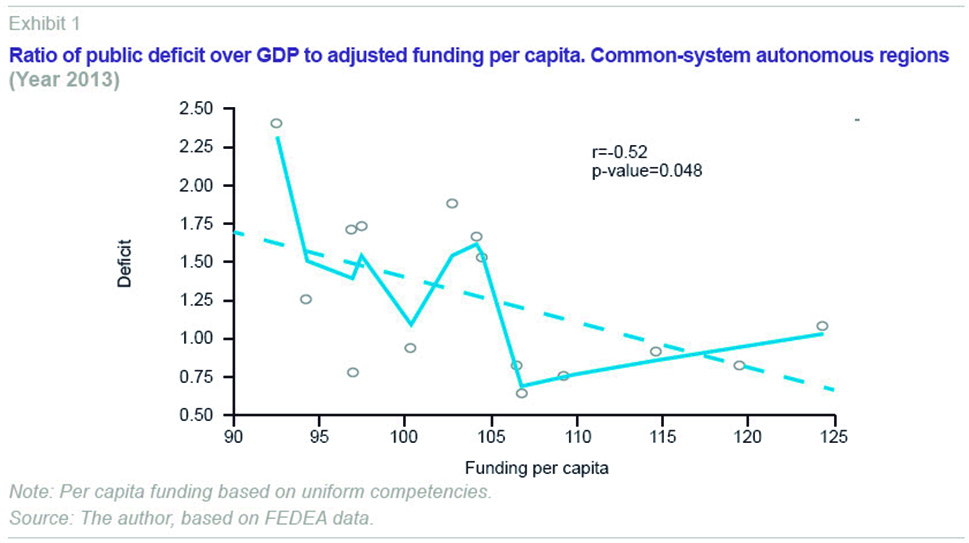

Exhibit 1 explores this idea in more detail, using 2013 data to compare public deficits over GDP and funding per capita adjusted for differences in spending requirements.

[3] The linear regression shows a negative and statistically significant relationship, with a simple correlation coefficient of -0.52. The nonlinear regression confirms the relationship, but also reflects that it is not the only relevant factor. There are individual behaviours and factors that go beyond the funding provided by the regional financing model. In particular, there seem to have been governments that have taken consolidation more seriously than others, accepting the electoral cost of austerity more and using their autonomy, particularly on the expenditure side, to meet objectives by making deeper cuts.

To ensure that regional governments cease to be a source of instability and fiscal non-compliance, a multidimensional strategy is required.

In legislative terms, rather than making the current legislation stricter, what is needed is to learn from the events of recent years and make the triggering mechanisms for the protocols in the event of non-compliance more automatic.

The deficit path set for the autonomous regions up to 2018 could be softened by reallocating the deficit quotas assigned to each level of government. One possible criteria is to use the share of each level of government in total spending. This option would lead to the autonomous regions’ having a third of each year’s deficit target. However, it is true that this criteria can be qualified, given the existence of transfers between the different levels of government.

Ceteris paribus, an increase in resources transferred to the autonomous regions will increase the central government deficit and reduce that of the regions. This would therefore alter the government´s budgetary restrictions without affecting the formal deficit targets. In short, discussion over the distribution of deficit targets cannot be isolated from the debate over regional funding. And it is precisely the reform of the latter that opens up the third of the dimensions to be changed.

It is imperative that the tax system in the regions in the “common system” (i.e., excluding the “foral” communities) be considerably strengthened, their budgetary restrictions tightened and the overall distribution of resources better matched to each region’s spending requirements.

The regions need to be given overall responsibility for obtaining the resources they manage and be weaned off their current dependence on the central government. Spain does not come out poorly in international comparisons as regards the percentage of tax revenue that is decentralised. For example, in the EU-25, it is the leader at the intermediate government level, ahead even of all the federal countries.

There are several weaknesses as regards the region´s tax system. These include: the lack of visibility of the autonomous regions’ taxing powers in the case of income tax and the huge delay with which the public and the administration notice the effects of changes in regional legislation; harmful tax competition in the case of wealth tax; the lack of regulatory powers over indirect taxation, even collection; and, the lack of a catalogue of types of taxes in the environmental and energy fields to bolster legal certainty and improve harmonisation.

It is also essential to impose stricter budgetary restrictions on regional governments, so as to force both those governing and those governed to accept the costs of their spending decisions, create incentives to use regulatory capacity, and, in short, increase fiscal responsibility and accountability. In particular, the extraordinary liquidity mechanisms from which the autonomous regions currently benefit should disappear as soon as possible.

Third, as regards the distribution of resources across territorial units, the way spending needs are calculated could be improved and arbitrary ex-post deviations, as currently occur, avoided.

Fourth, the current formula of advance payments on which common-system funding is based means regional governments back away from possible adjustments to budgetary execution in the face of negative economic shocks or other types of contingencies as they lack clear incentives to cut spending or raise taxes. In this regard, Hernández de Cos and Pérez (2015) make an interesting proposal that an adaptive mechanism be applied in which income forecasts are updated over the year and advance payments adjusted accordingly.

Finally, the debate on the social security system’s income and charges needs to be revisited. The reforms to the Spanish pension system in 2011 and 2013 significantly cut back long-term spending, but avoided addressing the income side and had less of an impact in the short term. Within the “Toledo Pact” there needs to be discussion of whether some pensions (survivors’ and orphans’ pensions) should be financed from general taxation, or if, alternatively, a special-purpose tax should be introduced.

Notes

As regards compliance with deficit targets, three factors caused some degree of confusion at both the technical level and public debate. The first factor was the methodological revision of the national accounts. Although in line with Eurostat directives, it affected nominal GDP calculations, and, therefore, had a denominator effect on deficit ratios. The second factor was the diverse interpretations of what is and is not included within the deficit figures. And the third factor was the revision of the targets, as was the case in 2014. In other words, the consolidation objectives were met thanks to: (i) the real and intense fiscal consolidation effort; (ii) a flexible interpretation of what is and is not considered as part of the deficit; and, (iii) the (slight) upward revision of the targets.

For an analysis of the PGE-2016, see Lago-Peñas (2015).

References

AIReF (INDEPENDENT FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY AUTHORITY) (2015a),

Informe de cumplimiento esperado de los objetivos de estabilidad presupuestaria, deuda pública y regla de gasto 2015 de las Administraciones Públicas (Report on expected compliance with the budgetary stability, public debt and 2015 government expenditure rule objectives), 17-7-2015.

— (2015b),

Informe sobre los Proyectos y Líneas fundamentales de los Presupuestos de las Administraciones Públicas en 2016: Subsector Comunidades Autónomas (Report on the projects and fundamental lines of the 2016 government budget), 30-11-2015.

COMISIÓN DE EXPERTOS (2014),

Informe de la comisión de expertos para la reforma del sistema tributario español (Report of the expert panel on reform of the Spanish tax system) (

http://www.minhap.gob.es/es-ES/Prensa/En%20Portada/2014/Documents/Informe%20expertos.pdf), MINHAP, February 2014.

DELGADO, M.; GORDO, L., and F. MARTÍ (2015), “La evolución de la deuda pública en España en 2014,”

Boletín del Banco de España, July-August: 41-56.

FEDEA (2015),

Observatorio Fiscal y Financiero de las CC.AA. Octavo Informe, November 2015.

HERNÁNDEZ DE COS, P., and J. PÉREZ (2015), “Reglas fiscales, disciplina presupuestaria y corresponsabilidad fiscal,”

Papeles de Economía Española, 143: 174-184.

LAGO-PEÑAS, S. (2015), “The 2016 General State Budget: Balancing fiscal consolidation and the electoral cycle,”

SEFO 4(5): 53-59.

LAGO-PEÑAS,S., and MARTÍNEZ-VÁZQUEZ, J. (2016), “El gasto público en España en perspectiva comparada: ¿Gastamos lo suficiente? ¿Gastamos bien?,”

Papeles de Economía Española, 147, forthcoming.

MINISTERIO DE HACIENDA Y ADMINISTRACIONES PÚBLICAS-MINHAP (Ministry of Finance and Public Administration) (2015a),

Actualización del Plan de Estabilidad del Reino de España 2015-2018 (Update to the Kingdom of Spain’s Stability Plan 2015-2018).

— (2015b),

Plan Presupuestario 2016 (2016 Budget plan), 11 September 2015.

— (2015c),

Publicación de los datos de ejecución presupuestaria (Publication of budgetary execution data), 22 December 2015.

Santiago Lago-Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics and Director of GEN, University of Vigo