The challenge of recapitalising Spain’s corporate sector

The intensity and duration of the COVID-19 crisis has raised the risk of a potential insolvency crisis in Spain’s corporate sector. In order to avoid this, targeted measures that utilise a variety of instruments, involve the role of the private sector, and reform bankruptcy procedures will be key.

Abstract: The protracted length and intensity of the COVID-19 crisis means that the initial measures designed to ensure the flow of financing to the corporate sector are no longer sufficient. In response to the first wave of COVID-19, the Spanish government provided loan guarantees to nearly one million enterprises, most of which are SMEs. While these loans involved attractive conditions, they nonetheless count as debt and have reversed a decade’s long deleveraging effort in the Spanish corporate sector. A wave of bankruptcies would have a deleterious effect on Spain’s productive fabric at a time when the economy’s recovery is highly vulnerable to shocks. However, any response to this potential risk must look beyond a rise in insolvency filings. Instead, efforts should also be made to reinforce the corporate sector’s financial structure so as to support investments in digitalisation and sustainability. Spain should consider adopting the highly targeted approach of other countries that utilise a wide variety of instruments and bolster the role of the private sector. Within this context, the Spanish government’s recent approval of a new 11 billion-euro aid package for SMEs and the self-employed, comprised of a direct aid fund, debt restructuring, and business recapitalization is a welcome development.

A deeper and longer than expected crisis

The risk of business failures rises the longer the pandemic drags on. What was initially considered a liquidity issue could transform into a solvency crisis with the potential to be even more widespread than the last financial crisis, which was more limited sector-wise.

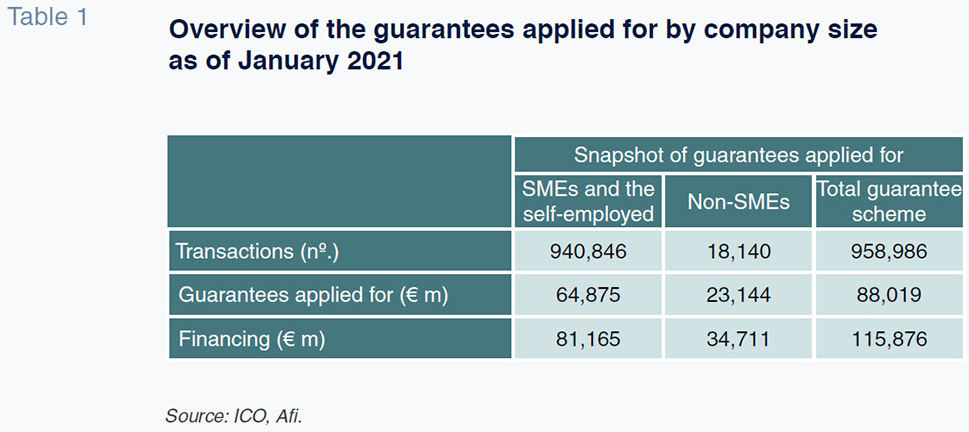

Importantly, state loan guarantees had a stabilizing effect during the initial lockdown. These guarantees prevented a collapse in financial flows as manufacturing plants were forced to shut.

Nearly one million enterprises, most of which are SMEs (including self-employed professionals), have benefitted from the loan guarantees. The government scheme provided attractive cost and repayment terms (initial maturity of five years, later extended to eight) and grace periods (initially, one year, then lengthened to two).

Despite these attractive terms, guaranteed loans are still nonetheless debt, and as such have to be repaid. They also imply a fresh spike in indebtedness after a decade of non-stop deleveraging in the corporate sector.

Between 2010 and 2020, Spain’s corporate sector deleveraged considerably, while its capitalisation (weight of own funds over total assets) increased by nearly 10 percentage points. However, the crisis has spurred a substantial accumulation of corporate debt that has wiped out almost half of the improvement in capitalisation observed over the course of the last decade. Significantly, the impact of the crisis on corporate financial health has been extremely uneven. In the sectors hit hardest by the crisis, (i.e., those most exposed to activities more reliant on physical presence or contact), the deterioration in solvency has been far greater. Also, the fallout from the crisis is likely to be far more intense for SMEs, which are more financially vulnerable.

The Bank of Spain, using a sample gleaned from its corporate balance sheet database, estimates that the percentage of SMEs experiencing financial pressure has increased from 13% in 2019 to 40% (30% of large enterprises) and that the percentage of insolvencies could go nearly as high as 20%.

Although a wave of bankruptcies would have a deleterious effect on Spain’s productive fabric, any response must look beyond a rise in insolvency filings. Instead, efforts should also be made to reinforce the corporate sector’s financial structure so as to support investments in digitalisation and sustainability.

The case for extending the scope of current measures

For large and/or strategic companies, the financial support programme rolled out last year earmarked an initial sum of 10 billion euros for their recapitalisation channelled through the state’s investment arm, SEPI. However, the remaining enterprises —neither large nor strategic— that account for over 90% of the nearly 3.3 million firms in Spain, had not been targeted with any recapitalisation mechanisms, despite their greater financial vulnerability.

The need to tackle recapitalisation or at least some form of partial debt relief is becoming more and more pressing. Indeed, the European Commission recently sent out a consultation asking member states for feedback about the possibility of offering some form of partial forgiveness on the guaranteed debt extended to those companies that have seen a significant fall in business volumes. That initiative would be benchmarked against the Payment Protection Program (PPP) in the US, under which over 6 million companies (whose revenue has contracted by over 30%) have benefitted —to the tune of more than 600 trillion dollars— from debt forgiveness.

To complement those partial debt relief measures (or as an alternative thereto), Spain’s companies, particularly its smallest firms, need significant recapitalising, an effort that will require the design of hybrid public-private initiatives in order to augment the limited stock of available public funds.

An international comparison

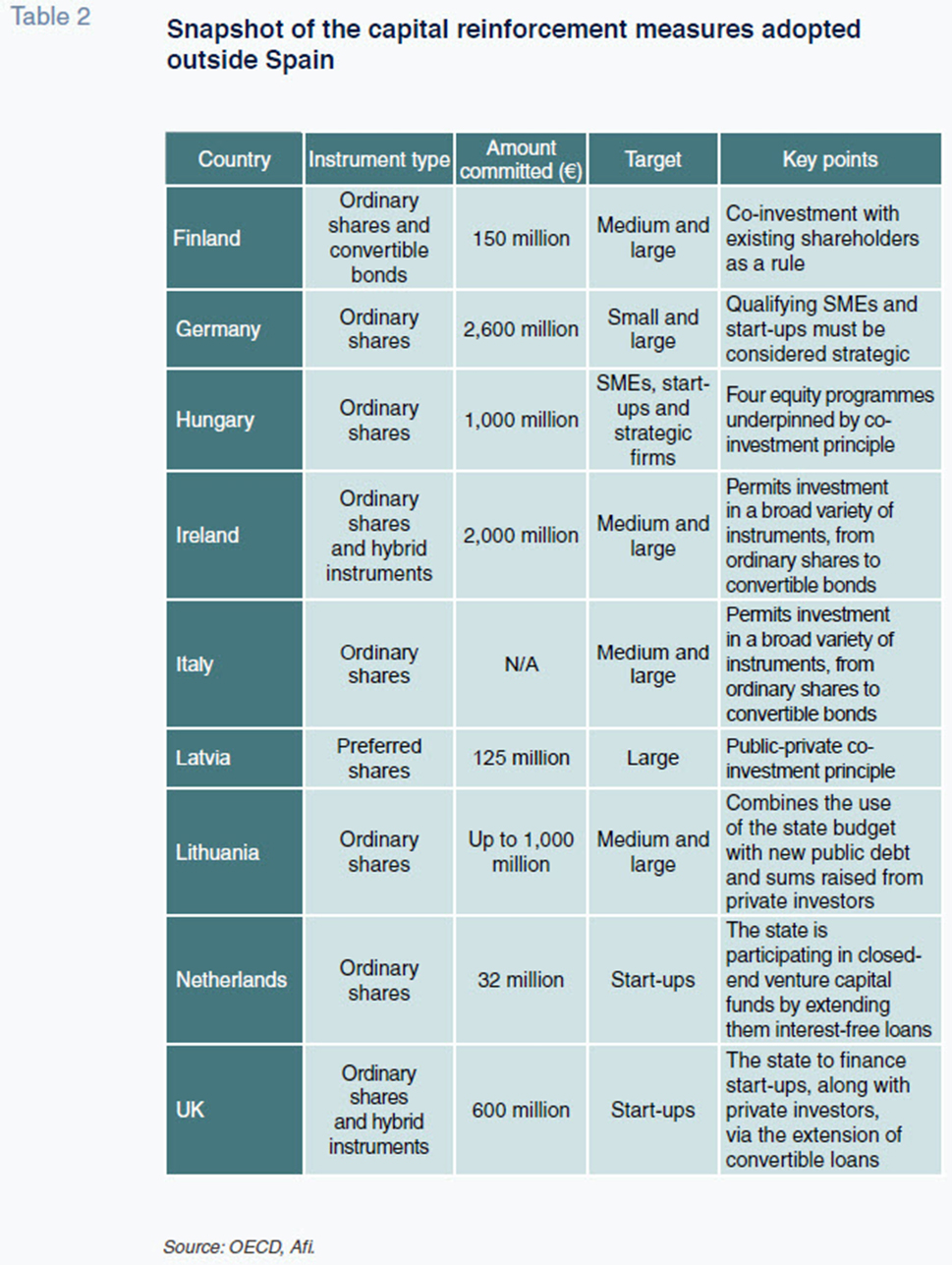

The urgent need to recapitalise the corporate sector is not an issue specific to Spain. In recent months, several countries have deployed measures designed to reinforce their companies’ capital structures, taking a range of approaches.

- Several countries, including Spain, as a first step, have focused clearly on their medium- and large-sized enterprises (Finland, Ireland, Italy and Lithuania, for example).

- Other governments have rolled out mechanisms targeted specifically at strategic SMEs (Germany) or SMEs in general (Hungary).

- Some countries’ measures have focused exclusively on start-ups (Netherlands and UK).

The table reveals common characteristics of these public support schemes:

- They contemplate a wide variety of instruments, not just common equity but also preferred shares and even convertible debt instruments.

- They are geared towards bolstering the role of private sector investment. In that context, the private equity sector has a clear role to play in reinforcing equity.

- Lastly, the terms strategic and viable are explicitly associated with virtually all the schemes. This is essential to preventing such mechanisms from propping up companies whose viability might already have been in doubt prior to the crisis.

The above schemes demonstrate that it is feasible to extend current measures to other important parts of the Spanish economy. The next section outlines specific approaches that facilitate this extension.

Focus of the newest measures introduced in Spain

The Spanish government has just passed a new 11 billion-euro aid package for SMEs and the self-employed, broken down as follows:

- Direct aid fund for SMEs and the self-employed, which encompasses the bulk of the funds (7 billion euros);

- Debt restructuring fund of 3 billion euros; and,

- Business recapitalisation fund of 1 billion euros.

Below is a description of the key characteristics of each core component:

Direct aid

The direct aid fund, with an envelope of 7 billion euros, is targeted at covering the fixed costs of business whose revenue contracted by at least 30% between 2019 and 2020. The regional governments will be in charge of distributing those funds, while the tax authorities will be tasked with verifying the revenue shortfall for eligibility purposes. The funds are expected to be made available to the regional authorities by the end of April. The purpose of the aid is to cover payables accumulated since March 2020 (supplier payments, wages, leases and borrowings).

This direct aid package is in turn sub-divided into two tranches:

- 5 billion euros for the mainland regional governments, to be allocated using the same criteria as are used to allocate the REACT-EU funds; and,

- 2 billion euros for the Canary and Balearic Islands.

The coverage level will depend on the size of the recipient businesses and their tax regimes. The regional governments will be able to cover up to 40% of the contraction in revenue for micro-enterprises and self-employed professionals and 20% for other companies. In parallel, the scheme assigns a fixed amount of 3,000 euros for self-employed professionals who pay tax under the objective assessment scheme, and sums ranging between 4,000 and 200,000 euros for other companies. The regional governments have yet to set the criteria for divvying up these new funds.

Financial restructuring

The fund earmarked for debt restructuring transactions has an envelope of 3 billion euros. It is targeted at firms that have secured state-guaranteed bank loans in the context of the pandemic. This package will include haircuts as a last resort. Coordination of this mechanism will be left in the hands of the banks, in the form of a code of best practices, taking advantage of their reach and business solvency knowledge.

The fund will intervene in three ways:

- Extension of the state-backed loan maturity terms, in addition to the extensions awarded in November 2020, and extension of the deadline for applying for such loans until December 31st, 2021;

- Conversion of credit facilities into profit-participating loans, via the state guarantee; and,

- Direct fund transfers for reducing principal on the loans arranged with state guarantees in the context of the pandemic.

In each arrangement, the state will assume the percentage it guaranteed (80% of the amount of credit in most cases) and the banks will bear the rest.

Business recapitalisation

The last vehicle, endowed with one billion euros, will be used to refloat SMEs, via COFIDES, the state development company, emulating the model pursued by the SEPI, the state’s industrial investment arm, for large and strategic enterprises. As with the latter, the new fund will have a range of investment instruments —debt, equity and quasi-equity— and the investments will imply state participation in the recipients’ future earnings. The state will invest in the recapitalised entities for eight years at most. The requirements for the recapitalisation mechanism include:

- Keeping the company operating until June 30th, 2022;

- Agreeing to not pay dividends; and,

- Agreeing to not increase senior management pay for two years.

Other schemes worth contemplating

Further development of market infrastructure

There is also scope for facilitating growth companies’ access to the capital markets via market infrastructure such as BME Growth.

[1] This refers to the creation of investment tax breaks and the subsidising of costs for public offerings and/or public investments in the share offerings of listed companies (similar to what is being done with the fixed-income instruments being listed on MARF). Such initiatives could increase the size of the market, its investor base and its depth.

The “democratisation” of equity investing in smaller-sized enterprises could also provide benefits. Efforts have already been made in the REIT segment, where the combination of stock exchange listings and benign regulatory and tax regimes have enabled real estate developments to attract equity financing via the capital markets.

Such an approach should be designed to tackle the two major limitations faced by private equity firms when it comes to investing in smaller-sized companies- limited research and investment oversight capabilities. The idea would be to create aggregated instruments that eliminate the investment selection and monitoring effect and facilitate direct investment by professional investors in an end vehicle.

Simplification of rules and flexibility of payments

We have outlined in detail the need to halt the rise in corporate insolvency through targeted recapitalisation. However, the reality is that for many companies, these measures will not arrive in time or in sufficient size.

Other initiatives are needed to target viable companies that require urgent debt restructuring if liquidation is to be avoided. The idea is to speed up and simplify court and out-of-court insolvency procedures to prevent bankruptcies. Currently, these proceedings are protracted and costly.

[2]

Introduction of such simplified rules and flexibility with payment plans could increase the likelihood that non-viable SMEs exit and viable ones in temporary distress are restructured immediately.

It is also important to recall that the public sector is, alongside the banks, one of these distressed companies’ main creditors and its unwillingness to exonerate public debt, such as taxes, loans from ICO and other public bodies and social security payments, has traditionally played against the successful conclusion of such proceedings.

Reforms should:

- Encourage pre-insolvency mechanisms with a preventative aim;

- Speed up and reduce the costs of insolvency proceedings; and,

- Allow the public administration to take part in debt restructuring agreements.

Conclusions

The protracted length and intensity of the COVID-19 crisis means that the initial measures designed to ensure the flow of financing to the corporate sector are no longer sufficient. The deployment of measures designed to reinforce Spain’s ailing companies’ capital structures is essential for tackling the ensuing challenge of modernising the productive model, with digitalisation and sustainability as the key levers. The decision to extend the measures passed in 2020 is therefore very welcome, as is the focus on SMEs, with new vehicles that do not exclude any business, regardless of whether or not they have availed of the state-backed loan facilities.

Notes

The BME Growth is a sub-market of Bolsas y Mercados Españoles, the Spanish company that deals with the organizational aspects of the Spanish stock exchanges and financial markets, which includes the stock exchanges in Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao and Valencia.

According to the OECD, 25 of its members have not systematically regulated special procedures for SME insolvencies. However, during the pandemic, countries such as Switzerland and the US did roll out specific measures for simplifying those mechanisms, including temporary relief from payment obligations for financially distressed companies and, in the US, increased access to a streamlined restructuring process for small businesses by broadening the debt-limit eligibility threshold. Introduction of such simplified rules and flexibility with payment plans could increase the probability of success and speed of viable SME restructuring.

References

BANK OF SPAIN. (2020). El impacto de la crisis del Covid-19 sobre la situación financiera de las empresas no financieras en 2020: evidencia basada en la Central de Balances [Impact of the Covid-19 crisis on the financial health of non-financial corporates in 2020: evidence gleaned from the repository of corporate balance sheets]. December.

ECB. (2020). Financial Stability Review. November.

OECD. (2020). Covid-19 Government financing support programmes for businesses.

—. (2021). Insolvency and debt overhang following the COVID-19 outbreak: Assessment of risks and policy responses. January.

ROYAL DECREE-LAW 5/2021 (of March 12th, 2021) on extraordinary business solvency support measures in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Official State Journal (BOE).

Irene Peňa and Pablo Guijarro. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.