Spain’s housing market in times of crisis: Will this time be different?

Unlike the previous financial crisis, the housing sector has proven to be resilient throughout most of the pandemic, with mortgages and housing transactions rebounding after an initial dip. Given that debt burdens are lower and housing affordability stronger than in previous years, the sector appears more likely to evolve than collapse.

Abstract: Many market observers have expressed concerns that the COVID-19 crisis could create vulnerabilities within the Spanish housing sector, leading to negative knock-on effects for the wider economy. However, Spain’s housing sector has performed better than many had initially anticipated. For example, in December 2020, new mortgages topped €5.4 billion, the highest reading since mid-2010. This favourable performance can largely be explained by government policies, such as furlough schemes and mortgage moratoria, that have protected Spanish consumers’ income, while ultra-low interest rates have ensured demand for housing has remained strong. Imbalances and market dislocations observed in the past appear to have corrected. Residential investment currently accounts for 5.4% of nominal GDP in Spain, which contrasts with the highs of 2006, when residential investment reached 11.8% of nominal GDP. Also, the spread between the gross rental yield and the 10-year sovereign bond yield is at a high, indicating that the presence of speculative demand in the rental market is much lower than it was in 2006-2013. Lastly, the debt burden and housing affordability indicators also look much better than in 2008. Going forward, bigger corrections in volumes than prices are expected. However, the prospect of ongoing government support and European recovery funds suggest that the sector is more likely to evolve than collapse as a result of the current crisis.

Introduction

The housing market plays a crucial role in macroeconomic stability. Its tight links to both the real economy and the financial system make it a spillover sector with the potential to amplify imbalances in either direction through multiple channels (wealth effect, loan non-performance, etc.). That became painfully obvious in Spain during the economic crisis of 2008. After the housing market bubble burst, the country witnessed a sharp contraction in construction sector employment, a collapse in prices and a surge in loan non-performance that ended up hurting the solvency of numerous banks and threatened to spread to the rest of the eurozone. Against that backdrop, one of the most pertinent questions at this juncture of the pandemic-induced crisis is will things be different this time? Could the sector end up destabilising the Spanish economy?

Situation in the housing market

One of the characteristics of the COVID-19 crisis is its asymmetric impact across countries, regions and sectors. The Spanish economy is proving to be one of the hardest hit, due to the high importance of the economic activities most reliant on social interaction, such as tourism and hospitality, where business metrics are at levels not seen since the late 1960s (foreign tourist arrivals, etc.). Other sectors, however, such as the pharmaceutical and food sectors have performed very well, responding flexibly to the changes in consumption patterns triggered by the pandemic.

The housing market is performing better than feared at the onset of the pandemic. The bad memories of the sector’s role during Spain’s last major recession and the fear of a drastic deterioration in the main drivers of demand (employment, household income, etc.) prompted worries that a sharp correction in volumes and house prices could spark a new downward spiral. That analysis failed to take into consideration the absence of major imbalances in the market (unlike in 2008) or the potential momentum from new trends such as working from home and the green transition.

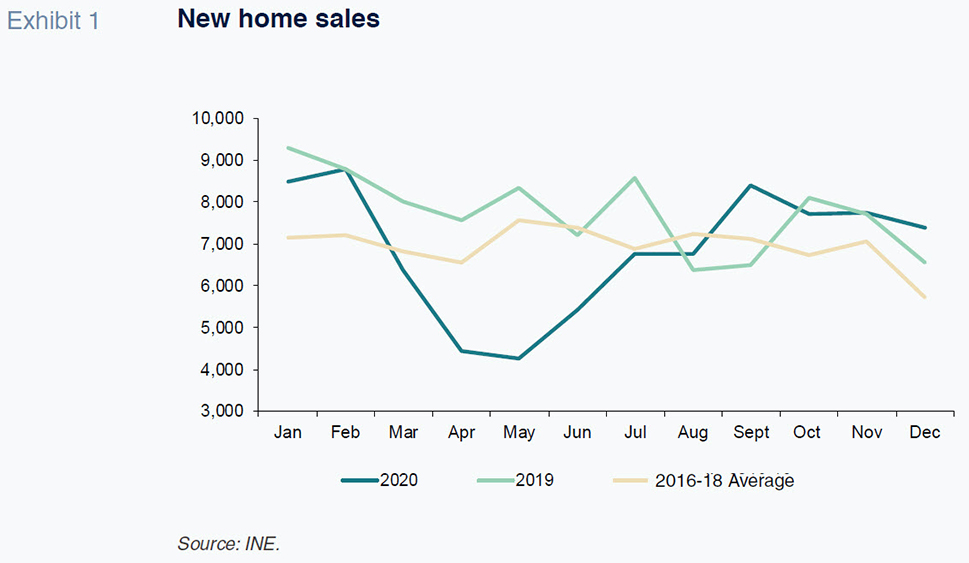

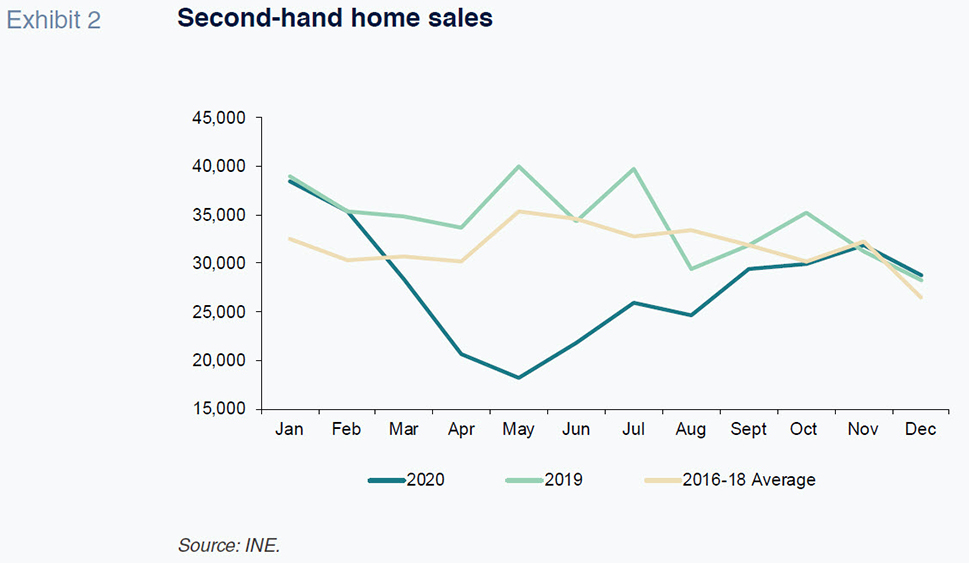

In fact, transaction volumes corrected very severely during the first weeks of the crisis (-57%), along with new mortgages (-20%). This is not surprising given the impediments to closing transactions in person (strict lockdown, closure of property registrars, etc.). However, from July the market began to recover, correcting much of the contraction sustained during the first half, thanks to pent up demand during the months of harsher restrictions and strong off-plan sales at developers. The second half of 2020 was marked by positive signals in terms of transaction volumes, prices and mortgage flows, a good barometer for measuring the sector’s momentum. In December 2020, new mortgages topped €5.4 billion in Spain, the highest reading since mid-2010 and a year-on-year growth of 18.2%. That growth was the highest in the eurozone, ahead of Germany (10.5%), Portugal (8.1%), the Netherlands (6.9%), Ireland (6.7%) and Austria (6.3%). The upward trend in new mortgages since the summer was sufficient to push the overall 2020 balance into positive territory (+0.9% to €44 billion), whereas back in April and June the contractions of around 50% foreshadowed a correction of at least 25%.

That back and forth was shaped, according to the latest bank loan survey, by the materialisation of purchase decisions deferred during the spring, as well as the emergence of new and different consumer needs. Indeed, the quarterly statistics published by the property registry reveals growing interest in houses with larger floor areas and open spaces (111 square metres is the new all-time high for the average new house size), as well as a surge in demand for single-family homes, which account for nearly one out of every four transactions and could explain the growth in the average mortgage loan size. Also, with rates ultra-low and lending competition intense, the share of fixed-rate mortgage loans is increasing. In 2020, that percentage rose to over 44% of new loans, compared to 34% in 2019 and 6% five years ago. In sum, we are seeing shifts in home buyer preferences that are set to change demand dynamics in the future.

The trend is very similar if we analyse housing transactions. In December 2020, 36,109 homes were sold in Spain (the best December since 2007), marking growth for the second month in a row (+3.7%) and reaffirming the recovery in demand. While the improvement was widespread in December, the uptick in sales of new homes (+13% year-on-year) was much stronger than that in second-hand homes (+1.6%), largely because the purchases closed before the onset of the pandemic were not cancelled, unlike at the start of the last crisis, indicating that expectations have not changed radically this time round. Demand strengthened as the year unfolded, although the annual balance was negative, at 417,768 transactions (down 89,700 from 2019). That gradual normalisation of activity is shaping the price stability observed in the market, despite the odd blip in the middle of the year. The repeat-sales house price index (IPVVR) shows a rebound in prices in the fourth quarter of 2020 (+1.0% for the quarter), which more than offset the weakness evidenced in previous quarters. Thanks to that year-end momentum, the year-on-year rate remained in positive territory (1.6% for the arithmetic index and 2.2% for the average index). In short, the easing already observed in price momentum before the arrival of COVID-19 has intensified but we are not seeing significant price correction. That being said, the indicators have been affected by market inactivity and the lack of inputs, so it is too soon to say that the sector is out of the woods, especially as the gap between supply and demand prices could widen as agents wait for the uncertainty to dissipate.

In a nutshell, since the summer, the housing market has performed better than initially expected. At the start of the pandemic, the fear was that we would see a significant correction in sales and prices. In the absence of more bad news on the economic front and pending the final snapshot of the impact of the crisis on the job market, the most likely hypothesis is that this time the housing market correction will be far more digestible than in the last crisis, with a bigger impact on transaction volumes than prices.

Market adjustments and imbalances

The trend in the key housing market indicators in the months following the onset of the crisis has been supported by certain economic policy responses (furloughs, moratoria, etc.) that have shielded household income and cushioned the initial impact of the pandemic. However, given the significant and ongoing uncertainty as to the trajectory of the crisis and when the extraordinary support measures might be rolled back, it is important to consider possible structural imbalances in the housing sector to assess its vulnerability in the event of a potential economic deterioration.

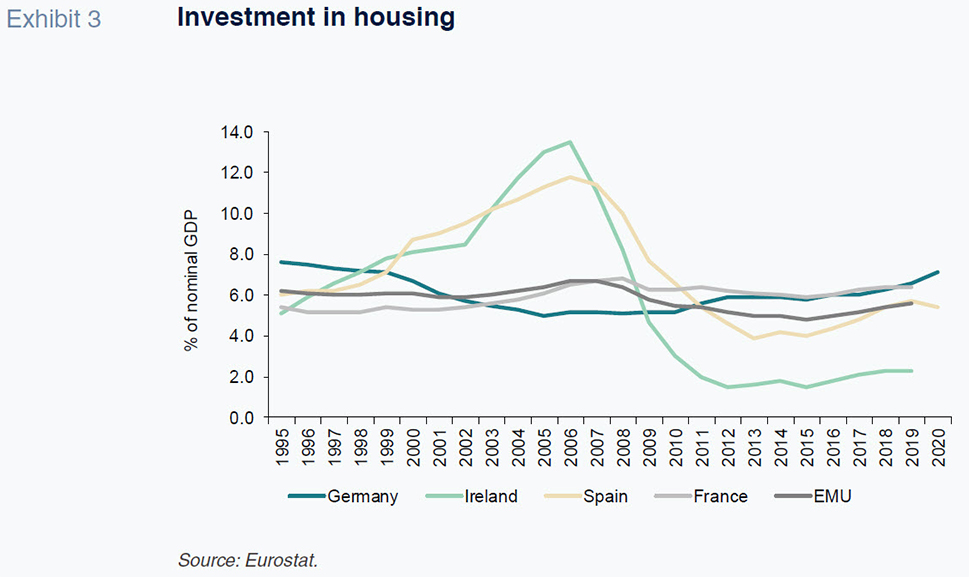

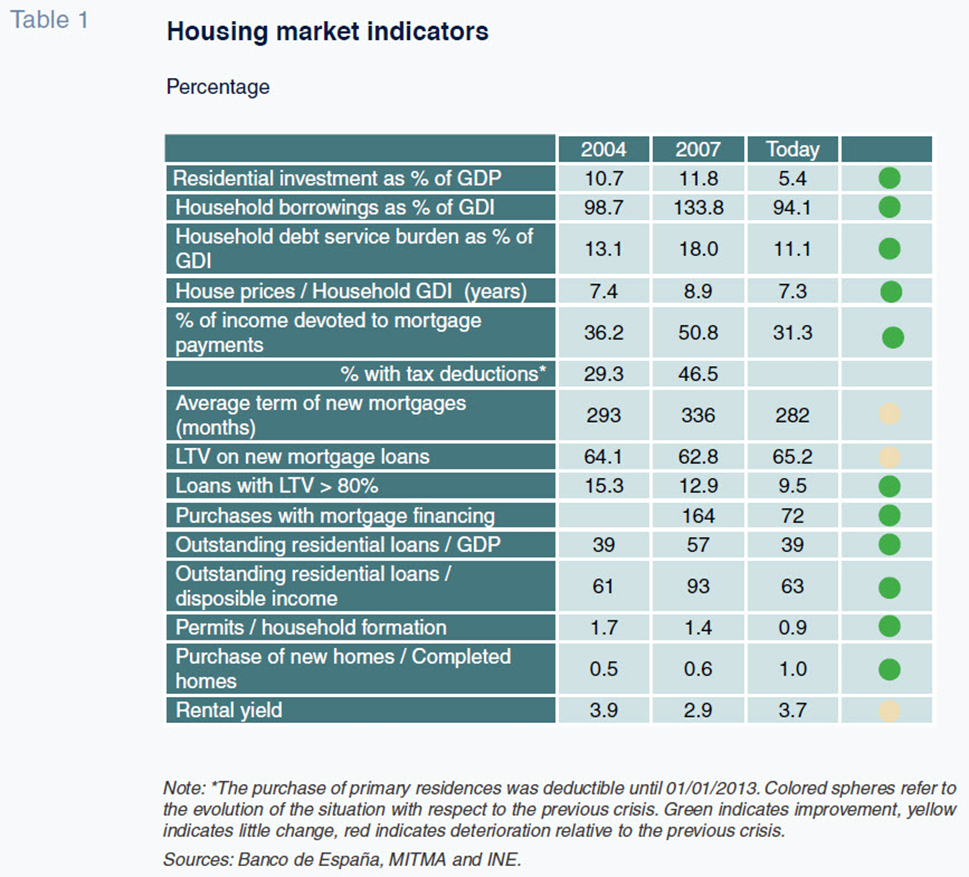

The first litmus test is the weight of residential investment in GDP and the trend in that metric since the last crisis. Residential investment currently accounts for 5.4% of nominal GDP in Spain, which is below the average for both Spain (7.2%) and the EMU (5.6%) over the last 25 years. That situation contrasts with the highs of 2006, when residential investment reached 11.8% of nominal GDP in Spain, nearly twice the EMU average (6.7%). These numbers suggest that many of the excesses of the last crisis have been corrected and activity levels are currently very much in line with those of Spain’s main EU peers.

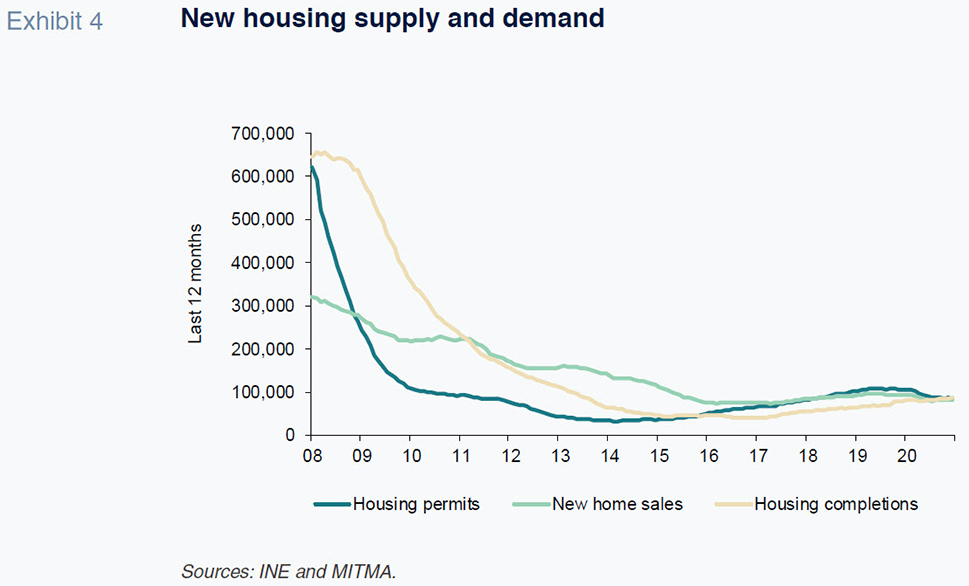

Another way of analysing the situation is to compare new housing development with household formation (potential demand). In 2020, that alignment was almost perfect (89,600 new households compared to 86,548 permits), again contrasting with the situation in 2008 when house permits (nearly 900,000) were virtually double household formation (450,000). The same reading is gleaned from the high absorption of finished housing by the market in 2020 (83,878 completed houses compared to 82,543 new home purchases). Housing supply therefore appears to be closely aligned with demand without any signs of surplus production. However, certain developers may be adjusting their output for the new paradigm, thereby “phasing in” their developments to test the strength of demand and reduce risks. At any rate, considering that household formation ground to a halt in the wake of COVID-19, it is possible we could see a shortfall of new housing in the near term, unlike what happened in 2008.

On the price front, the distance from previous highs remains significant (over 23%) and, more importantly, some of the relative valuations measures are very far from what might be considered ‘stretched’. For example, the spread between the gross rental yield (3.7%) and the 10-year sovereign bond yield (0.3%) is at a high, indicating that the presence of speculative demand in the rental market is much lower than it was in 2006-2013, when the gross rental yield was lower than the sovereign bond yield in Spain. Only an investor expecting sharp price gains would be willing to buy assets with an annual return that is lower than the risk-free rate of return.

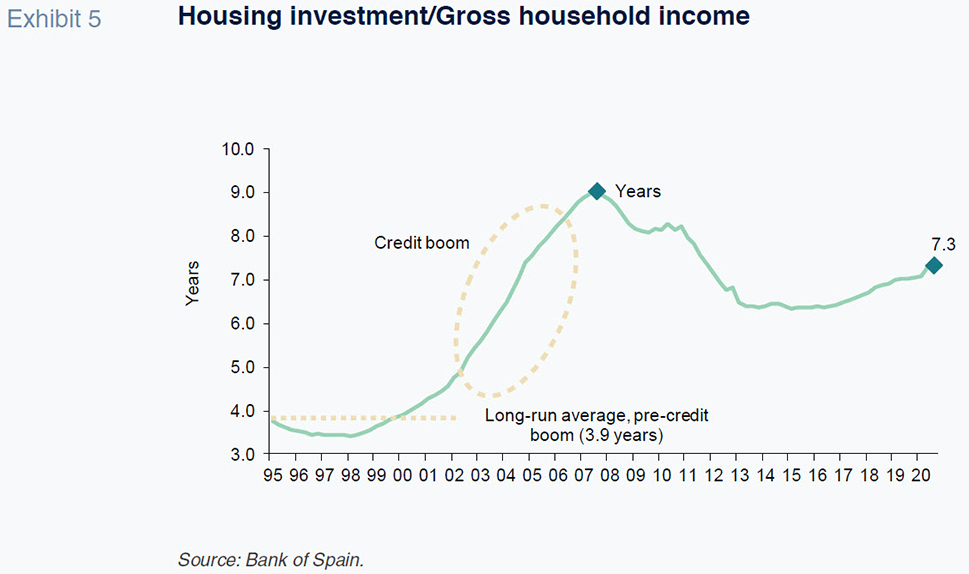

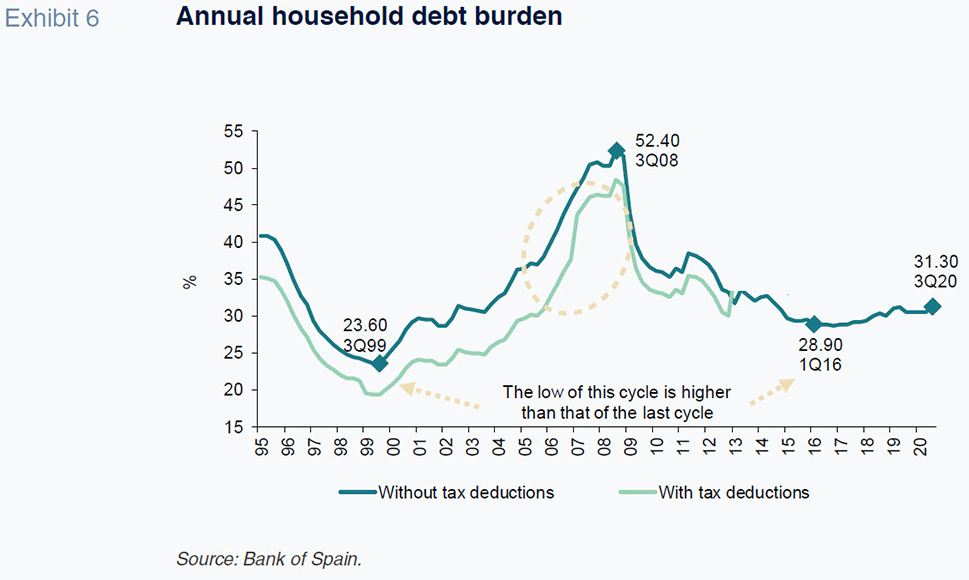

The debt burden and housing affordability indicators also look much better than in 2008. Buying an average sized home in Spain requires 7.3 years’ pre-tax income, down from nine years at the height of the bubble (6 years during the low of 2014-2016). Nor are household debt servicing burdens excessive, particularly in comparison with Spain’s EU peers. In Spain, just 8.5% of households have to cover house-related expenses (rent or mortgage payments) of over 40% of their disposable income, which is below the EU average (9.8%) and below the figures in Italy, Germany and the UK, among other countries. Moreover, household leverage (94.1% of GDI) has come down very significantly since 2007 (133.8%) with households earmarking just €3.55 billion to mortgage debt service in 2020 (€40.12 billion in 2008). Meanwhile, housing affordability, measured as the percentage of income a household has to devote to mortgage payments each month, lies at a reasonably comfortable level (31.3%), well below the 2008 peak of 52.4%. The stability of prices in recent quarters and the expectation that interest rates will remain at current levels for quite some time suggest that is unlikely that the debt service burden will revisit worrying levels in the medium-term. Here the key, however, is for the growth in household income to keep pace with the growth in housing prices.

Lastly, the improvement in affordability is not attributable to an “excessive” easing of borrowing terms. The average mortgage loan term stands at 23.9 years, compared to 28.3 years in 2008, while the percentage of mortgages awarded at a loan-to-value (LTV) of over 80% remains near the low (9.5% of the total). On the supply side, the financial sector has reduced its exposure to the construction and development sectors to under 20% of their corporate loan books, compared to 50% in 2008 (30% in the EU). In general, therefore, it can be said that the excesses of the previous decade have been reduced by a very significant degree, which means that the sector’s ability to absorb the inevitable shock the crisis will produce, sooner or later, is also substantially better.

A comparison with the state of the sector across Europe yields similar conclusions. Using the data published by the European Mortgage Federation, the five countries with the highest relative burden of housing costs were Sweden (outstanding residential loan balance of 89.2% of GDP), the Netherlands (89%), Denmark (83.2%), Luxembourg (56.1%) and Belgium (55.7%). Expressed in terms of household income, the most leveraged nations were the Netherlands (outstanding residential loan balance equivalent to 183% of household disposable income), Sweden (177.8%), Denmark (173.3%), Luxembourg (154%) and the UK (100.6%). In Spain, outstanding residential loans represent 39.2% of GDP and 62.7% of household disposable income. Those ratios, following years of household deleveraging in Spain, are below the EMU average (44.2% and 73.6%, respectively). A situation that contrasts starkly with that of 2008, when the stock of residential loans accounted for 90% of Spanish disposable income (65% in the EMU).

The deleveraging effort (in May 2021 the stock of residential loans will have been in decline for a decade) has improved Spain’s positioning relative to Europe in terms of the debt burden assumed to purchase a home and virtually eliminated the excesses of a decade ago. The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), the body tasked with macroprudential supervision of the EU financial system and the prevention and mitigation of systemic risk since 2020, has a similar take. In its recent report (April 2020), in the section devoted to residential real estate risk monitoring, Spain was not part of the group of countries that were issued warnings (Czech Republic, Germany, France, Iceland and Norway) or that which received recommendations (Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Sweden).

Conclusions

Despite the fears and concerns at the start of the crisis, the housing market has not emerged as one of the sectors most affected by the pandemic in Spain. Following a drastic initial correction, activity levels have recovered quicker and with greater intensity than in other sectors and the key indicators have virtually revisited pre-pandemic levels. House prices have extended the slowing momentum observed pre-COVID-19, but the initially feared sharp correction has not materialised. The policies devised to protect the economic agents’ income (furlough schemes, mortgage moratoria, etc.) and to maintain ultra-lax financing conditions have propped up that performance.

It is true that the market is characterised by many asymmetries, between: regions; new and second-hand housing; and, resident and non-resident demand. In general, however, the feeling is that this time around the housing sector is not at the epicentre of the crisis, as there are no signs of overheating, over-valuation, surplus supply or excessively lax financing terms. Moreover, the financial situation of Spain’s households is more robust than it was during the last crisis. The market may nevertheless need to rebalance and reconfigure in response to potential shifts in demand patterns (search for larger houses, further away from cities and with green spaces) and digest the correction we may see in the rental market. It seems more likely we will see bigger corrections in volumes than prices.

It looks like the housing market will play a different role than in the last crisis. Particularly if the macroeconomic support policies are left in place as long as is necessary and Spain leverages the European recovery funds for refurbishment and energy efficiency programmes.

References

José Ramón Diez Guijarro. IE Business School and CUNEF