The regulatory sandbox and potential opportunities for Spanish FinTechs

Regulatory sandboxes, one of the best means of accelerating financial innovation while controlling risks, are already operating successfully around the world. Efforts are underway for Spain to be among the next group of countries to put their own sandboxes into motion.

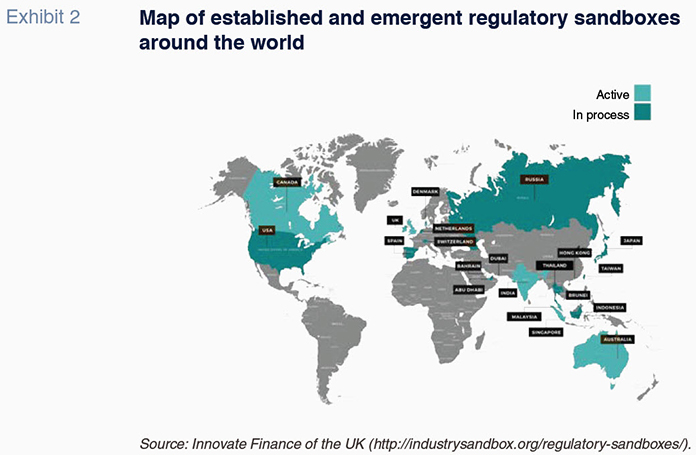

Abstract: Efforts to strengthen the global financial system in the wake of the crisis have made it more solid and resilient, but simultaneously created a more onerous post-crisis regulatory framework. The new requirements have also had a significant impact through various channels on today’s financial institutions. Within this context, the regulatory ‘sandbox’, widely used in the FinTech and digital banking arenas, stands out for its many advantages. These advantages include the ability to promote competition, ultimately in the benefit of consumers, by allowing companies to test innovative products, services and business models in a real or live market environment, while ensuring the existence of appropriate safeguards. The UK has successfully pioneered the sandbox concept back in 2015, but currently regulatory sandboxes are also already operating with positive results in Singapore, Abu Dhabi and Switzerland. Spanish authorities too have recently announced their intentions to launch a national sandbox, but implementation should move quickly in order not to lose the first-mover advantage relative to other continental European peers.

Introduction

Banking regulation is ubiquitous nowadays. And it is coinciding with the multiple opportunities and challenges deriving from information and data processing. However, there are also risks associated with sensitive issues such as cyber-attacks, money laundering and, in some instances, identity theft. This has prompted countless financial and non-financial entities to earmark vast sums of money to ensuring the security of their data and stringent compliance with data protection regulations. The sheer number of new laws, regulatory frameworks and compliance regulations has grown considerably. In parallel, seismic changes in the geo-strategic landscape, such as the Trump administration’s protectionist measures and Brexit, have generated additional regulatory changes that are affecting the corporate and financial sectors deeply. This regulatory situation is costly and complex.

Recent estimates

[1] suggest that financial institutions will need to devote an average 10% to 15% of their staff to compliance and data security. Major banks such as HSBC, Deutsche Bank and JP Morgan are already spending roughly 1 billion dollars a year on regulatory compliance and oversight. Despite this, the fines paid by certain entities to regulators since the crisis of 2008 are running at over 321 billion dollars.

According to the RegTech Supplier Report

[2], around 50,000 regulatory documents have been published in the G20 since 2009, which translates into an average of 45 new documents a week. MiFID II alone has generated 30,000 pages of regulatory text.

Regulation vs. innovation

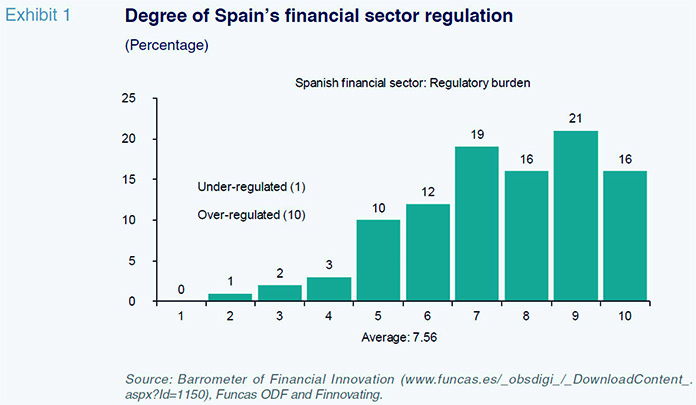

The post-crisis regulatory framework is more exacting and this has had an impact on financial institutions. This is evidenced by sector executives according to the first edition of the Financial Innovation Barometer compiled by Funcas and Finnovating: 37% of those surveyed believe that the financial sector is very over-regulated (scores of 9 and 10 on a scale of 1 to 10) and 35% believe that it is considerably over-regulated (scores of 7 and 8). In contrast, just 3% believe it is under-regulated (1 to 3).

The increase in the regulatory burden runs the risk of smothering innovation in any sector or country by creating an element of uncertainty surrounding innovations that are not subject to any regulations at the time of their creation.

What is a sandbox and what does it do?

The term ‘sandbox’ is widely used in the FinTech and digital banking arenas as it is conceivably one of the best ways of accelerating financial innovation while controlling risks so as to protect end consumers.

The best and simplest definition is that of a controlled environment or safe space in which FinTech start-ups or other entities at the initial stages of developing innovative projects can launch their businesses under the ‘exemption’ regime in the case of activities that would fall under the umbrella of existing regulations or the ‘not subject’ regime in the case of activities that are not expressly regulated on account of their innovative nature, such as initial coin offerings (ICOs), crypto currency transactions, asset tokenisation, etc.

The goal of a sandbox is to promote competition, ultimately in the benefit of consumers, by allowing companies to test innovative products, services and business models in a real or live market environment, while ensuring the existence of appropriate safeguards.

The 10 advantages of a sandbox

To understand the advantages that a regulatory sandbox could have for a European or IberoAmerican country like Spain, it is important to analyse the potential benefits.

The 10 main contributions are analysed here:

- Fostering of innovation and job creation. Sandboxes allow a working environment from which to launch new financial or insurance business models that make intensive use of data and new technology to create innovative and more efficient solutions for customers.

- Fine-tuning of legislation. Sandboxes create an environment in which to observe how regulatory frameworks should be adapted to embrace the changes the FinTech sector requires so as not to falter on the innovation front.

- Minimising risks. It is the ideal instrument for enabling the supervisors to keep an eye on the newest innovations and for fostering a mutual learning process with respect to the risks and opportunities posed by the use of new technologies in new business models.

- Cutting costs. Lower costs and shorter time to market for innovative FinTech and InsurTech products and services.

- Attracting investment. Sandboxes help countries position themselves in the international hub of foreign capital for innovative sectors in which the UK, Australia, Japan, Canada, Hong Kong and Singapore stand out.

- Fostering competition. By initially reducing regulatory requirements and lowering barriers to entry, competition intensifies, ultimately translating into better products and services for end consumers.

- Benefits for customers and financial inclusion. Sandboxes facilitate entry into the market for newcomers, all of which ultimately benefits end customers. This can take the form of more and/or better products and services, lower prices or technological innovation. They also enhance access to financing and further financial inclusion for the more marginal segments of society.

- Talent redemption. Nowadays, many entrepreneurs choose where to launch their start-ups as a function of the ease of starting up a new business, to which end they analyse business licences and regulatory frameworks. A sandbox can help prevent an exodus of talent from a country.

- Attracting innovation. The rollout of one of the first sandboxes in the European Union could draw start-ups from other member states that do not have such attractive regulatory frameworks.

- European and Latin American financial hub. The Spanish FinTech and InsurTech Association (AEFI), the first to put together an alliance of FinTech associations representing over 20 countries, has launched a 10-point declaration for a Latin American sandbox.

Sandbox regimes

Exemption mode. Under the exemption regime, the sandbox would allow FinTech and InsurTech firms to enjoy a test period during which they can build up to meeting the requirements for obtaining a licence to operate, for example, in the securities, banking, payment services or insurance markets (e.g., capital, solvency, corporate governance requirements, etc.) gradually. They would not be required to comply with all of these requirements from the outset, an issue that could constitute a clear impediment for the economic viability and survival of many companies; rather, they would be asked to meet them on a staggered basis as they achieve a certain level of maturity. Innovation would be a prerequisite for authorising the exemption.

Not subject mode. Elsewhere, under the ‘not subject’ mode, the sandbox would allow FinTech and InsurTech companies that pursue activities that have yet to be specifically regulated (e.g., ICOs, neobanks and the brokerage of crypto currencies) to begin to test their products in a safe or controlled test space so that these kinds of products and services are launched onto the market with the backing of the regulator and, therefore, the required safeguards for the end customer and the financial system itself, increasing legal certainty and credibility in the process.

A sandbox for Spain

The introduction of a sandbox in Spain would imply multiple advantages for the development of the FinTech and InsurTech sectors.

Firstly, exclusively focusing on the benefits that would accrue to the FinTech and InsurTech sectors, it is undeniable that the creation of a regulatory framework tailored and proportionate to the needs of entities at the initial stages of development or maturity could boost their proliferation, as well as lowering launch costs and shortening the time to market of these entities’ products and services.

One of the first obstacles faced by the FinTechs is, precisely, the complex bureaucratic system that is so hard to navigate during the earliest stages of development. A controlled test environment would help alleviate the bureaucratic burden by providing legal certainty to those entities seeking to operate in the market but unfamiliar with traditional financial regulations.

There are, therefore, loftier reasons that go beyond the mere individual benefits for the FinTech or InsurTech players or even the customers who may get to buy their products and services: there are reasons of public interest.

As a result, the introduction of a regulatory sandbox would allow certain FinTech and InsurTech firms to enjoy a test period during which they would be entitled to build up to the requirements for obtaining a regular licence slowly and gradually. Specifically, they would not be required to comply with all of these requirements from the outset.

Implementation: Attribution of powers to the Spanish regulators / supervisors (DGSFP, Bank of Spain, CNMV)

In order to roll out a sandbox in Spain, the law that governs the concept, along with the enacting regulations, will have to assign powers to the existing regulators for the processing, supervision and regulation of the entities benefitting from a sandbox authorisation or licence.

As set out in the sandbox proposal made by the AEFI (published in March 2018), the role of the supervisor could be confined to four phases, namely: (i) application; (ii) evaluation; (iii) testing; and, (iv) post-testing or exit.

(i) Application. The supervisor would be tasked with reviewing sandbox licence applications and reporting to the applicants within one month of their submission as to whether or not their applications have been accepted.

(ii) Evaluation. Having passed the application round (in which the supervisor would rule whether the FinTech firm’s application is admissible), the complexity of the project submitted by the firm and other analytical factors would be specifically evaluated, giving the applicant the chance to rectify any errors or provide any information their applications may lack.

This evaluation phase would end with the supervisory body’s decision as to whether or not to grant the sandbox licence. Regardless, whenever the evaluation phase ends with the turning down of an application, the supervisor would be required to inform the applicant which criteria and/or requirements it did not meet, thus giving it the chance to present a new and qualifying application.

The concession of a sandbox licence could also be made conditional upon compliance by the applicant with a series of requirements that at the date of granting of the licence are not met but that could be met by the applicant within a short period of time.

(iii) Testing. Once in possession of a sandbox licence, the entity would enter the testing phase, during which it would have to report to the supervisor from time to time on the progress made. In addition, the entity would be required to inform and notify its customers that the financial service being offered is at the time being provided under a sandbox arrangement, duly alerting them of the associated risks.

The testing phase (which may last between 12 and 36 months for B2C businesses and between 48 and 56 months for B2B businesses) would end when the entity surpasses one of the established thresholds (in terms of customer numbers or revenue, for example) or because the testing period has elapsed. However, for FinTech or InsurTech activities or firms that are still not subject to regulation at the end of the sandbox testing period, the competent supervisor could grant successive or indefinite permit extensions.

(iv) Post-testing or exit. At the end of the testing period, the sandbox licence extended by the supervisor would expire and the entity that had enjoyed the authorisation would be required to leave the sandbox. The regime could contemplate the possibility of extending the sandbox period so long as the permit holder applies for an extension to the supervisor at least one month before it is due to expire and presents sufficient grounds for the extension. It would be up to the supervisor to decide whether or not to extend the licence on a case by case basis and its decision would be final (not subject to appeal).

Once their licences expire, the entities would be allowed to start to market the financial services tested in the sandbox at a larger scale, so long as:

- The supervisor and the sandbox beneficiary agree that the expected results have been obtained; and,

- The sandbox entity is ready to meet all applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

Successful applicants would be required to present a final report summarising the results of their tests before transitioning outside the sandbox.

Geo-strategic analysis: Best international practices and lessons learned

UK case study

The UK was the first country in the world to establish a regulatory sandbox. A report was published in November 2015 with the aim of helping the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) to foster effective competition in the interests of consumers.

That report outlined the main benefits a sandbox would target:

- Reducing the time and, potentially, the cost of getting innovative ideas to market;

- Enabling greater access to financing for innovators, by reducing regulatory uncertainty;

- Enabling more products to be tested and, thus, potentially introduced into the market;

- Allowing the FCA to work with FinTech businesses to make sure that appropriate consumer protection safeguards are built in to their new products and services.

The initiative presented in November 2015 ultimately took effect in June 2016 when the first round of cohorts was called.

Progress made by the British sandbox. Early indications (the overview of year one) suggest this sandbox is providing the benefits it set out to achieve. Access to the regulatory process offered by admission into the sandbox has reduced the time and cost of getting innovative ideas to market.

The direct feedback provided by the cohorts during and after the tests in their final reports indicates that this aspect of the sandbox programme has proven highly valuable in helping them understand how the regulatory framework applies to them, accelerating market entry and reducing start-up costs.

The British sandbox in figures. The following conclusions stand out from the information provided in the Regulatory Sandbox lessons learned report published by the FCA in October 2017:

- 75% of the firms accepted into the first cohort successfully completed testing.

- Around 90% of the firms that completed testing in the first cohort are continuing toward a wider market launch following their test.

- The majority of firms issued with a restricted authorisation for their test have gone on to secure a full authorisation following completion of their tests.

- At least 40% of the firms which completed testing in the first cohort received investment during or following their sandbox tests.

- The sandbox has facilitated a significantly higher number of tests than initially anticipated, covering a wide range of sectors and product types.

Who participated? During the first two cohorts, the British sandbox received applications from 146 firms; 50 of those were provided with support with their test design, implementation and supervision. Not all of the firms progressed to testing their solutions in the sandbox: nine firms were unable to attain this milestone for differing reasons.

Sector breakdown. The most active sectors in the first two cohorts were the following (in order of importance):

- Retail banking

- General insurance

- Wholesale

- Retail investments

- Retail lending

The sandbox encouraged applications from all sectors. However, a majority of the firms which tested in the first two cohorts came from the retail banking sector.

Regional breakdown. According to this report, the majority of the firms in the sandbox during the first two cohorts are based in London. However, this trend appears to be changing. Approximately 35% of the firms participating in the second cohort are based outside of London, representing a marked increase with respect to the first cohort. Applications for sandbox authorisation came from all around the UK, including Scotland, East Midlands and South East of England. Applications were also received from firms based outside of the UK in countries including Canada, Singapore and the US.

This evidences the ability to attract talent from abroad and the geo-strategic positioning commanded by countries with operational sandboxes.

Size of firms. The sandbox provides support to innovative firms regardless of their size or maturity. However, the sandbox has clearly been most popular with start-up companies and those that are not yet authorised by the FCA. Note that over 83% of the cohorts were start-ups, the rest of the companies availing of this arrangement being medium- and large-sized enterprises.

New uses of technologies. Nascent technologies can play a key role in delivering innovative products and services that can improve on those currently available. This can be by enhancing the quality or reducing the price of offerings, or by increasing access for consumers. Below is a description of distributed ledger technology (DLT), more commonly known as blockchain technology.

DLT is a rapidly developing technology with exciting potential to enable firms to meet the needs of consumers and the market more effectively. We are observing how DLTs such as blockchain can be used to reduce costs, improve security and trust between groups of participants and enable services to be provided at a greater speed.

Some of the firms authorised by the British sandbox have begun to use this technology in their internal processes, rendering their operations more efficient and generating cost savings.

Singapore case study

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (“MAS”) has also introduced the regulatory sandbox concept to bring greater flexibility in testing FinTech products, thereby increasing the probability that they will reach the market, whether in Singapore or abroad.

Financial institutions and other firms with an interest can apply for access to the sandbox in order to experiment within the innovative financial service production process. As with the British and Australian experiences, all within a well-defined space and duration, tailored case by case.

Swiss case study

The Swiss Federal Council (SFC) was also one of the first regulators to show initiative in creating a sandbox to reduce barriers to entry for FinTechs.

As stated by the SFC, excessive red tape can stifle innovation and creativity in any market. The regulator noted in its proposal that all too often, politicians and policy-makers believe they are doing the right thing by creating rules and regulations designed to protect people such as themselves. Unfortunately, however, the downside can be a sluggish economy and low job creation. Despite the fact that regulations are extremely important and necessary, new rules must be drawn up with care. The Swiss authorities correctly concluded that a “dynamic FinTech system can contribute significantly to the quality of Switzerland’s financial centre and boost its competitiveness”.

Moreover, Switzerland is already favored by fintech for many reasons, including its innovative and competitive market, the decentralised political system, and the tendency of Swiss authorities to allow for self-regulation of the financial sector. The fact that four of the five most valuable ICOs were initiated in Switzerland speaks to its popularity within the fintech industry. This established network combined with the uniqueness of the Swiss political and regulatory environment strongly suggests that Switzerland is among the best placed to become the European hub for ICO activity.

The Abu Dhabi case study

The Financial Services Regulatory Authority (FSRA) of Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) set out its proposal for a “Regulatory Laboratory” (“RegLab”), a tailored framework that allows firms deploying innovative technology in the financial services sector to conduct their activities in a controlled and cost-effective environment.

As the first such initiative in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, the RegLab was formulated specifically to cater to the unique risks and requirements of FinTech participants, and incorporates extensive feedback from key local and global stakeholders. The FSRA said that the RegLab continues to promote its objective in developing a stable and sustainable financial services sector in Abu Dhabi, while fostering innovation within scoped parameters buffered by risk-proportionate regulatory safeguards.

The ADGM recently admitted a new batch of start-up FinTech firms to its RegLab. The 11 local and international FinTech start-ups will work under the umbrella of the FSRA, one of the ADGM’s three independent authorities, to develop and test their products within a controlled environment of “isolated space”.

Current situation in Spain

In early April, the Ministry of Economy announced the upcoming implementation of a regulatory sandbox in Spain with the goal of facilitating innovation in financial services and their development. The launch date is not yet determined but it is estimated that this instrument could be operating in Spain no later than the fourth quarter of 2018.

The idea is for Spain to position itself at the forefront of efforts to stimulate financial innovation as there is currently an attractive window of opportunity given that very few countries have set up a financial regulatory sandbox. Spain would be one of the pioneers in continental Europe or Latin America. This window of opportunity will not remain open for long, however, as countries such as France, Italy, Mexico and Brazil are working very intensively on launching their own sandboxes.

In addition, there is growing talk of international sandboxes, such as that proposed by the UK in its FinTech Sector Strategy Report of March 2018.

There is also increasingly persistent chatter about a possible European sandbox although this is not likely to materialise in the near future. Regardless, the opportunity is there for the taking for the countries most daring in their sandbox creations and support for financial innovation.

Notes

Rodrigo García de la Cruz. CEO of Finnovating