Assessing the role of Spain’s AIReF in the context of EU fiscal policy

The work of the AIReF has helped to support progress on budget stability and, by increasing the reputational costs of non-complying public administrations, it has enhanced fiscal governance in Spain. Going forward, among addressing other challenges, the AIReF should strive to preserve its independence.

Abstract: In an effort to make progress on EU fiscal consolidation, the need for member states to have independent fiscal institutions (IFIs) is gaining acceptance. Spain’s IFI, the AIReF, was created in 2013 with the mandate of guaranteeing government compliance with the principle of budget stability. The results of a review of its first years of operation, in line with the OECD’s recent findings, show that the institution has consolidated its independence and credibility. The AIReF has helped to support progress on budget stability and, by increasing the reputational costs of non-compliance, enhanced fiscal governance within Spain and the EU. Nevertheless, the AIReF still faces noteworthy challenges apart from preserving its independence, including accessing necessary information, improving the methodology of its projections, and increasing the impact of its recommendations.

Introduction

On the economic front, the European project is, for a range of reasons, in the midst of challenges and reassessment. A combination of three factors: (a) the impact of the economic crisis and its management from a political standpoint; (b) the UK referendum vote to leave the EU and the reaction by the remaining member states; and, (c) national economic policy preferences that are not always mutually compatible or synchronised are raising serious questions about the future of the European Union and of the eurozone.

As is often the case in crises, there is a certain amount of consensus regarding the facts, greater diversity of opinion regarding the causes, less agreement again about the responsibilities of the various parties and open confrontation regarding ideas and proposals as to how to fix the problem.

To organise the debate, the outstanding areas for improvement to enhance EU economic governance are usually grouped into three: i) reform of financial sector architecture; ii) reform of institutional architecture; and, iii) reform of fiscal architecture (Claeys, 2017; Wolff, 2017; Bénassy-Quéré et al. 2018; Jones, 2018).

This paper concentrates on the third aspect, the fiscal framework, and uses it to analyse the role of the first independent fiscal institution (IFI) created in Spain, the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (known as the AIReF for short) in helping to underpin fiscal discipline and the sustainability of public finances.

In the next section, we outline the current fiscal framework in the EU and the key factors determining the effectiveness of an IFI in helping to support sound fiscal policy. Then we analyse the AIReF’s first years in operation. To this end, we examine a recent review of the institution by the OECD and analyse the recommendations made by the AIReF between 2014 and 2016. Lastly, we present a set of conclusions.

The EU’s fiscal framework and the role of independent fiscal institutions

The EU’s fiscal framework dates back to the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) adopted in 1997. The pact included a preventative arm and a corrective arm, both of which were designed with the overriding goal of facilitating and injecting credibility into the excessive deficit principle enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty.

More specifically, the SGP set two fiscal rules for the member states: a deficit ceiling of 3% of GDP and a public borrowing limit of 60% of GDP (Claeys, Darvas and Leandro, 2016). However, as is well known, the pact has encountered serious enforcement issues. Indeed, nearly half of the member states were in breach of the borrowing rule for most years between 1999 and 2014, notably including France and Germany (Andrle et al. 2015).

In response to the SGP’s lack of effectiveness, the EU’s fiscal framework has been reformed several times. The Six-Pack (2011), Fiscal Compact (2012), the Two-Pack (2014) and the creation of the European Fiscal Board (EFB) in 2016 stand out in this respect (Claeys, Darvas and Leandro, 2016).

Assessments of the current state of the EU’s fiscal framework are varied. There is an element of consensus that the successive rule changes have yielded a framework that is overly complicated, scantly transparent and poorly functioning. Against this backdrop, there are proposals calling for the modification of the current framework to address its lack of transparency and effectiveness (Andrle et al., 2015; Claeys, Darvas and Leandro, 2016). Elsewhere, there are also calls for more radical overhaul of the existing framework in light of its complexity, ineffectiveness and in some instances even counter-productive effects during the crisis (Manesse, 2014).

The official stance taken by the European institutions, expressed in the last major strategic document about the future of the EU, the Five Presidents’ Report, is however silent on the advisability or need to modify the fiscal framework and rules (Juncker et al., 2015).

Parallel to this rather low-profile official stance, debate on EU fiscal policy persists in a quest to strike a balance between two basic objectives (Bénassy-Quéré et al., 2018):

- Taking measures designed to boost discipline in the member states; and,

-

Pursuing reforms that have stabilising effects on the EU member states.

Within the first group of measures lies the idea of reforming the existing fiscal rules and the various agreements reached subsequently with the idea of simplifying them, making them more effective and enforceable. The second category of reforms includes new forms of temporary budgetary transfers among member states. As a corollary to this approach, the majority appears to be leaning towards finding a credible formula for the non-bailout principle, i.e., the formal commitment that the states experiencing financial stress should not receive financial aid from the other member states unless they restructure their sovereign debt first.

From that perspective, in order to make progress on consolidation of the EU’s fiscal framework, the need for the member states to have independent fiscal institutions is gaining acceptance. In fact, the ‘Two Pack’ stipulates that the eurozone member states put in place “independent bodies for monitoring compliance with numerical fiscal rules” (Regulation [EU] No. 473/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council).

The arguments in favour of these bodies are clear-cut. IFIs, acting independently, tend to curb the discretion with which policy makers manage their public finances, reducing their “deficit bias”, as is well documented in the empirical literature. Nevertheless, the institutional design, dimension and breadth of duties tasked to the nearly 40 IFIs in existence at present vary significantly from one country to the next, even within the EU.

According to the specialist literature (Beestma and Debrun, 2018), the attributes an IFI needs to make an effective contribution to the functioning of a fiscal framework are essentially three:

- Independence;

- Communication power; and,

- The degree to which the political system engages with the IFI, not just in theory but in practice, by embracing the budget stability objective and the IFI’s specific mandate.

The first attribute, independence from political power, is crucial and enables an IFI to earn credibility vis-a-vis citizens and national and international economic agents. In fact, according to von Trapp and Nicol in Beetsma and Debrun (2018), it would appear that the IFIs and their respective governments are aligned on this principle as the level of independence of the OECD IFIs averages over 80% (in line with the estimated level of independence of the AIReF). As for the second attribute, optimum communication of the IFI’s mission and recommendations, it is vital that the IFI’s communication reach expands so that the reputational cost for the political powers of adopting irresponsible fiscal conduct increases. Lastly, the third element, good-faith cooperation between the Executive and the IFI, is a prerequisite for enabling independence and communication.

It is important to remember that just as a state can set up an IFI, it may also, if the circumstances made so doing desirable, adjust it to suit its purposes, tweaking its mandate or circumscribing its responsibilities. For further insight into this matter, see the references to the Hungarian case in the contributions by Wren-Lewis, von Trapp and Nicol, Wyplosz, Wehner, Page and Kopits in the volume published by Beetsma and Debrun (2018).

Analysis of the AIReF’s activities

Background

Spain’s IFI, the AIReF, was created in 2013 with the mandate of guaranteeing compliance by the government – at all levels – with the principle of budget stability enshrined in Article 135 of the Spanish Constitution, amended in 2011. The AIReF’s activities are governed mainly by Spanish Organic Law 2/2012 (April 27th, 2012) on Budget Stability and Financial Sustainability (the Stability Act).

The Stability Act establishes three fiscal rules, in keeping with the SGP and the EU’s fiscal framework: (a) Spain’s governments may not run a structural budget deficit; (b) growth in public spending may not exceed the economy’s nominal growth (this is known as the “spending rule”); and, (c) the ratio of public borrowings to GDP may not exceed 60%. The transition period for application of these fiscal rules spans until 2020. The Stability Act also reinforced the mechanisms in place for preventing breaches and creates new ones (Hernández de Cos and Pérez, 2013 and Kasperskaya and Xifré, 2018).

The AIReF carries out its duties independently of the government even though formally it is attached to the Ministry of Finance and Civil Service. The AIReF’s main source of financing is the supervisory fee that all of the governments covered by its reports are obliged to pay.

The AIReF’s main activity is to issue the reports and recommendations legally-mandated to it, including assessment reports on macroeconomic forecasts; projects and key headings in the various governments’ budgets; the governments’ initial budgets; and compliance with the budget stability, public debt and spending rule targets. The AIReF’s mandate includes the assessment and evaluation of the credibility of various economic forecasts and budgets.

The AIReF’s oversight remit encompasses all levels of government in Spain: the central or state government, the regional governments, the local governments, including all of the bodies under their governance, and the Social Security administration. More recently, the AIReF has become involved in the development and monitoring of ‘spending reviews’, i.e., analysis of the effectiveness of the spending programmes.

As a result of its analysis and oversight work, the AIReF draws up recommendations addressed to the various governments and ministries containing proposals for improving and flagging indications of the breach of the budget rules. The AIReF conducts this activity under the scope of the ‘comply or explain’ principle, as is customary at IFIs. This means that when an administration receives a recommendation from the AIReF, that administration must either comply with it or provide a reasoned explanation as to why it does not. Every quarter the AIReF publishes the responses received from the administrations in question, which has the effect of increasing the ‘reputation costs’ for institutions that fail to adopt its recommendations.

The recommendations for which a ‘comply or explain’ response is mandatory are in turn divided between: (i) recommendations stemming from shortcomings in information (‘scope recommendations’); and, (ii) recommendations stemming from matters of substance (‘substantive recommendations’). The first include requests for additional information and access to the full data needed by the AIReF. The second set of recommendations inform the administrations of the initiatives and measures they need to take in order to comply with the principles of financial sustainability and budget stability, including the legally-stipulated preventative and corrective measures. Lastly, the AIReF also issues: (i) opinions and guidance on good practice that are not compulsory; (ii) studies about specific methodologies related to its field of intervention; and, (iii) a data lab.

Analysis of the AIReF’s recommendations

This section analyses the recommendations issued by the AIReF distinguishing between the recipients, the type of recommendation issued and the contents of the recommendations, based on the institution’s annual reports. At the time of writing, the annual reports available are those corresponding to 2014, 2015 and 2016, so that the analysis is limited to those three years.

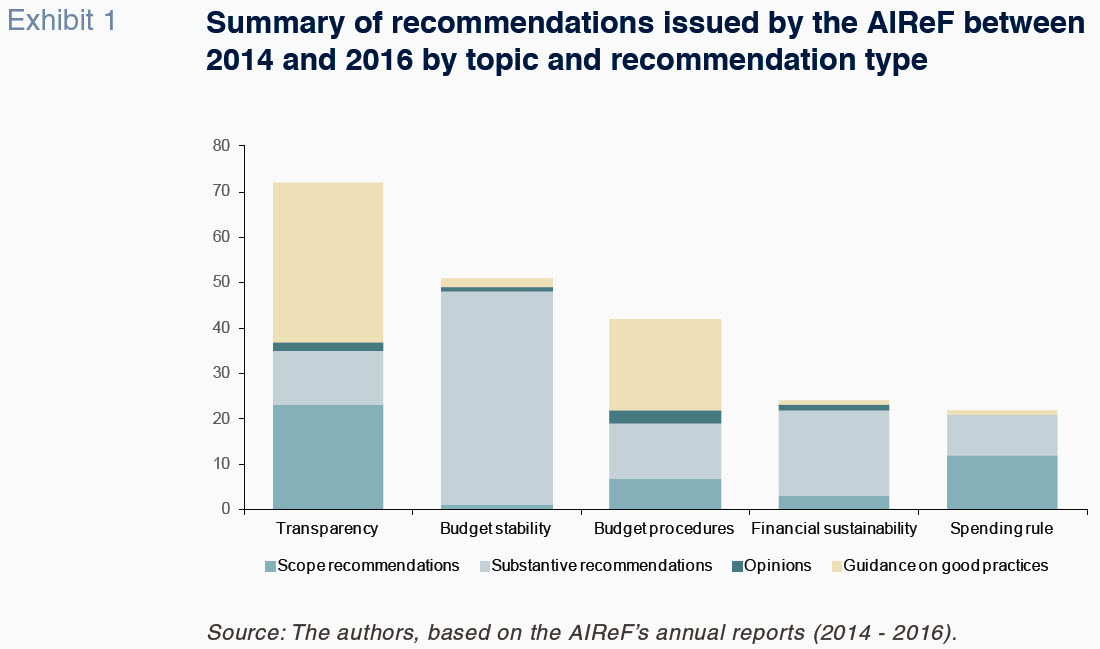

Exhibit 1 provides the breakdown of the recommendations, opinions and good practice guidance issued by the AIREF by topic and type of recommendation during its first three years in operation.

The matters concerning transparency are the most frequent. Within this heading, the two main types of recommendations issued correspond to (i) guidance on good practice, which are not considered binding in terms of the ‘comply or explain’ principle; and, (ii) ‘scope recommendations’. Therefore, the difficulties encountered in accessing the information needed and the quality of the data received have constituted the biggest challenge faced by the AIReF in doing its work optimally. The AIReF even reached the point of a legal dispute with the Ministry of Finance, which had been requiring it to present information queries and data requests through a centralised information pool without directly engaging with the entities involved (von Trapp and Nicol, 2018). The European Commission got involved in this conflict (European Commission, 2017) taking the AIReF’s side and, as a result, the ministry corrected its initial stance, facilitating access to the required information (Ministry of Finance, 2017).

The second most frequent type of recommendation relates to budget stability, with nearly all of the recommendations made in this area taking the form of ‘substantive recommendations’ and therefore subject to the ‘comply or explain’ principle. The fourth category by volume of recommendations – those addressing financial sustainability – similarly consists almost entirely of ‘substantive recommendations’. The third most popular category relates to budgeting procedures; in this instance the most common type of recommendation takes the form of ‘guidance on good practice’, i.e., recommendations that do not require the recipient administration to respond in ‘comply or explain’ format. Lastly, the fifth category, which addresses the spending rule, mainly features ‘scope recommendations’, indicating that the AIReF has encountered shortcomings in the information provided in terms of adequately appraising the matter.

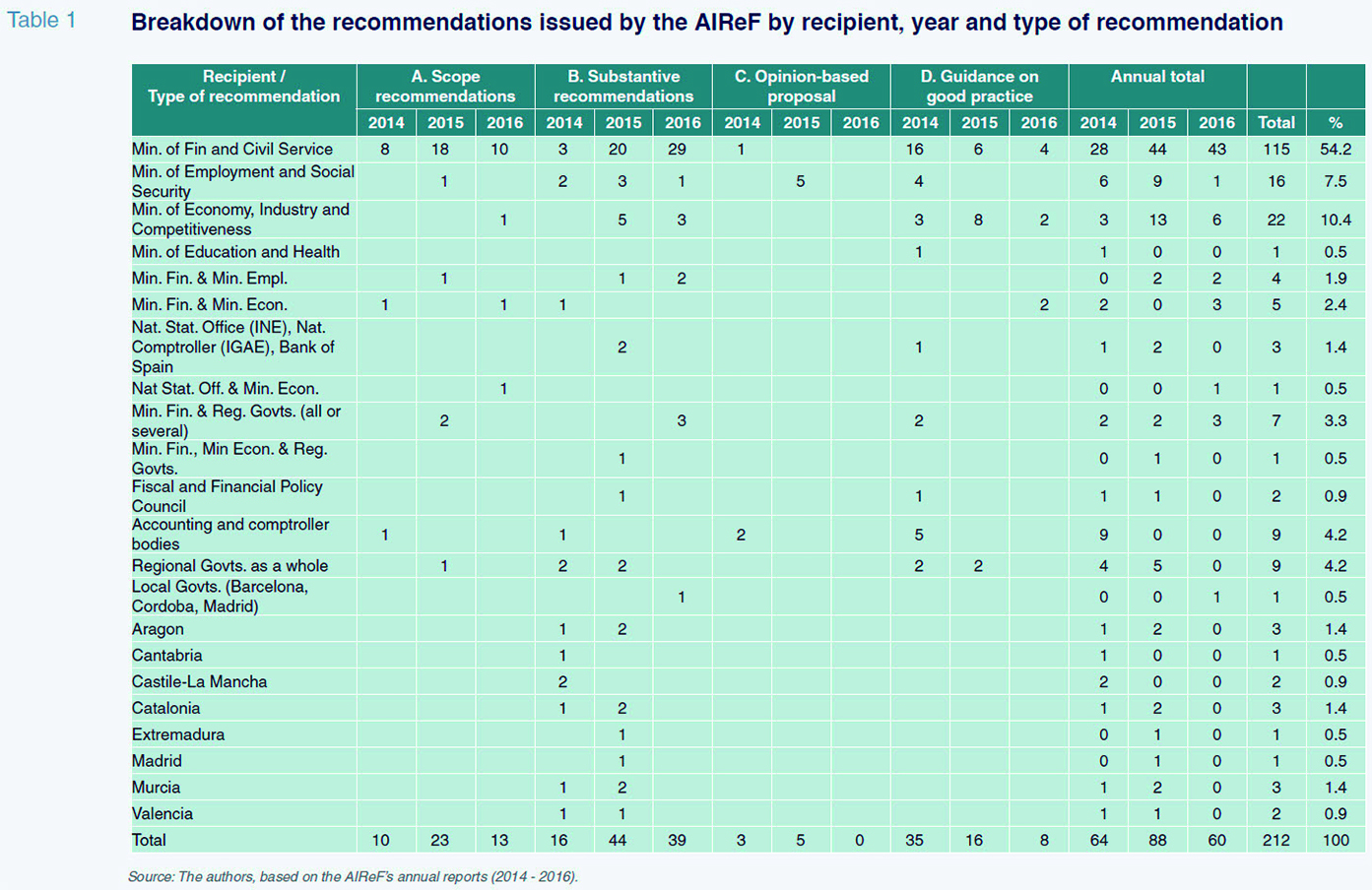

As for the recipients of these recommendations, Table 1 breaks down the recommendations, opinions and guidance issued by the AIReF between 2014 and 2016 by recipient and year.

As the Table shows, the main recipient of the recommendations, opinions and guidance issued by the AIReF is the Ministry of Finance and Civil Service, to which this IFI is attached, accounting for over half of all the observations made. This in turn reflects the fact that it is the ministry that dictates the regulations and methodology governing a good part of the budget items for which the various administrations are then responsible. As a result, recommendations regarding fundamental regulations that apply to all administrations have to be addressed to this ministry. The recipient of the next highest number of recommendations is the Ministry of the Economy and Competitiveness, which is responsible for preparing the macroeconomic forecasts and economic scenarios underpinning the general state budgets and other financial planning tools. It is followed by the Ministry of Employment and Social Security. In fact, the recommendations addressed exclusively to the various ministries (the three listed above plus the Ministry of Education and Health) represent over three-quarters (77%) of all the recommendations issued by the AIReF during the period analysed.

After the ministries, the entities receiving the highest volumes of recommendations from the AIReF are the IGAE, Spain’s general state comptroller, and the regional governments as a whole. Here it is worth noting that in several instances, the recommendations issued by the AIReF are addressed simultaneously to more than one institution, usually a ministry and one or more regional administrations.

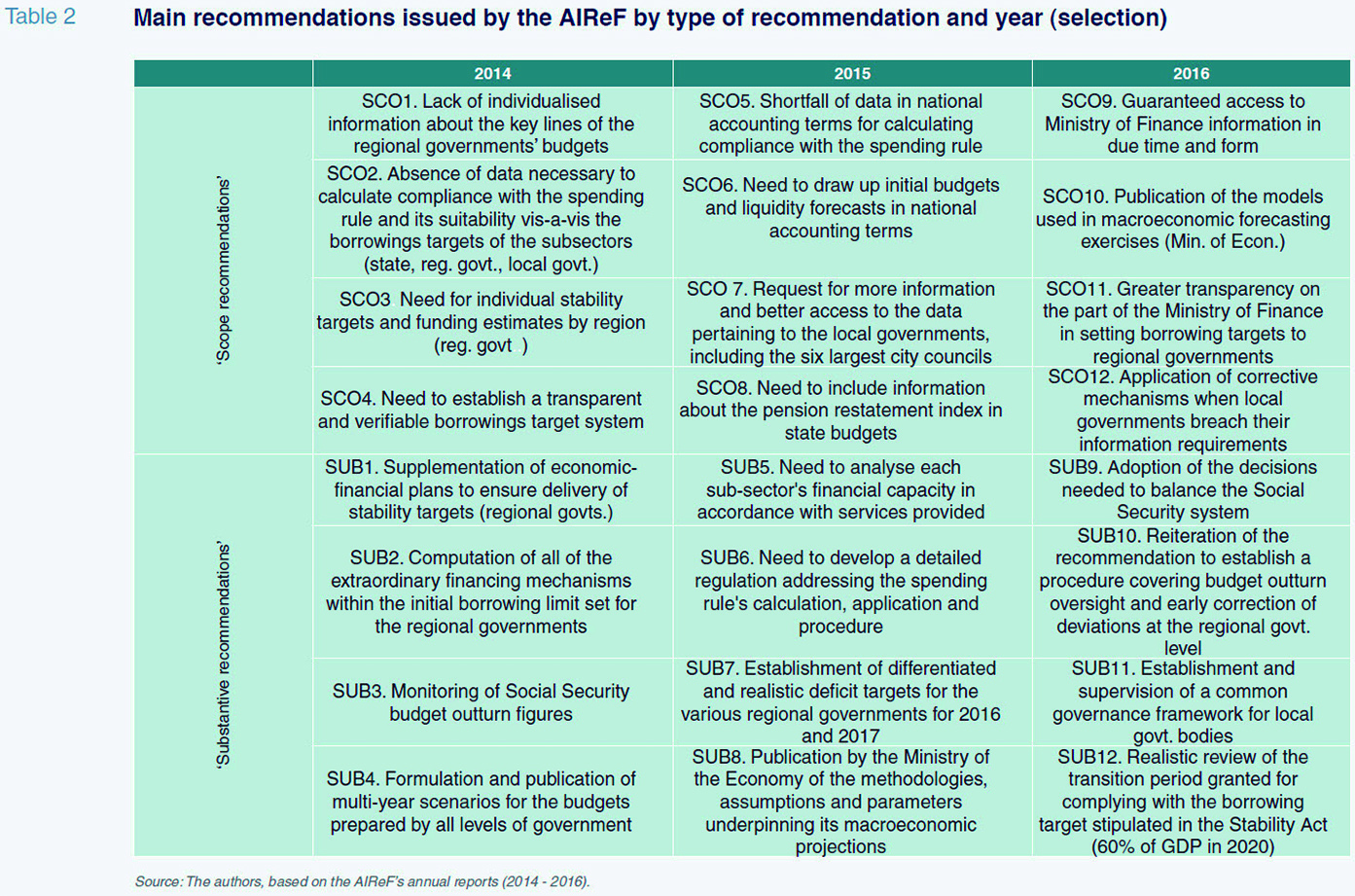

Table 2 rounds out the analysis by sorting the AIReF’s recommendations by topic and year. This table reproduces a selection of the key topics addressed in the reports issued by the AIReF between 2014 and 2016. Note that this is a partial selection in an attempt to exemplify the issues receiving the greatest attention in the institution’s first three years in existence. The table and subsequent analysis is limited to the two types of recommendations covered by the ‘comply or explain’ requirement,

i.e., ‘scope recommendations’ (SCO) and ‘substantive recommendations’ (SUB).

The first topic that stands out relates to the numerous references to the gaps encountered by the AIReF in attempting to compile the information it needs. Warnings about the lack of information are continuous and affect virtually all levels and sub-sectors of government (see for example SCO1, SCO2, SCO5, SCO7, SCO8, SCO9, SCO11, SUB3).

Related with this issue, the analysis also reveals the requests addressed by the AIReF, mainly to the ministries, asking for better explanations of the methodologies used to prepare the forecasts, models, etc. that are in turn used as the basis for setting budget targets (SCO4, SCO10, SCO11, SUB8).

Here it is worth underscoring the emphasis placed by the AIReF on the ‘spending rule’ stipulated in the Stability Act, highlighting the difficulties encountered in making it work in practice. The AIReF has repeatedly alerted the Ministry of Finance about the need to develop a methodology and a practical manual for its calculation and the advisability of setting up dedicated taskforces to address this issue within the Fiscal and Financial Policy Council and National Local Government Committee (SCO2, SCO5, SUB6).

Another relevant and recurring issue during the AIReF’s first years in operation, and an area in which it has defended a different stance to that taken by the government, is the need to set different deficit targets for the different regional governments (SCO2, SCO3, SCO11, SUB5, SUB7). The AIReF is of the opinion that, given the differences among the various regional governments in terms of starting positions and medium-term scenarios, it would be advisable to set different and specific targets for each region with the aim of rendering them more feasible and credible (refer to Escrivá, Janeba and Langenus in Beetsma and Debrun, 2018). Related with this point, the AIReF has also repeatedly manifested the need to design and effectively apply preventative measures in order to prevent target breaches, particularly at the regional and local government levels (SCO12, SUB10, SUB11).

Other topics often raised in the AIReF’s reports include the need to revise the roadmap for delivering on the public borrowing target of 60% of GDP by 2020 in order to make it more feasible and credible (SUB12); the recommendation to have initial budgets and liquidity forecasts drawn up at the national accounting level (SCO6); the advisability of drawing up and publishing multi-year budget scenarios at all levels of government (SUB4); and the need to take measures designed to balance the Social Security system’s finances (SUB9).

By way of a brief footer, note that in 2017, most of the recommendations issued by the AIReF continued to emphasise the importance of implementing preventative and corrective measures and the need to reinforce the consistency of the fiscal rules contemplated in the Stability Act.

Summary of the independent assessment of the AIReF: OECD report of 2017

In November 2017, the OECD published a review of the AIReF (von Trapp et al., 2017). This assessment, committed to by the President of the AIReF, was undertaken by a group of five independent experts (two members of the Budgeting and Public Expenditures Division of the OECD’s Directorate for Public Governance, two experts on independent fiscal institutions from the Netherlands and the United States and one Spanish academic peer) following the OECD’s own methodology (OECD, 2014).

In general terms, the assessment concludes that in the first years of operation the AIReF has consolidated its independence.

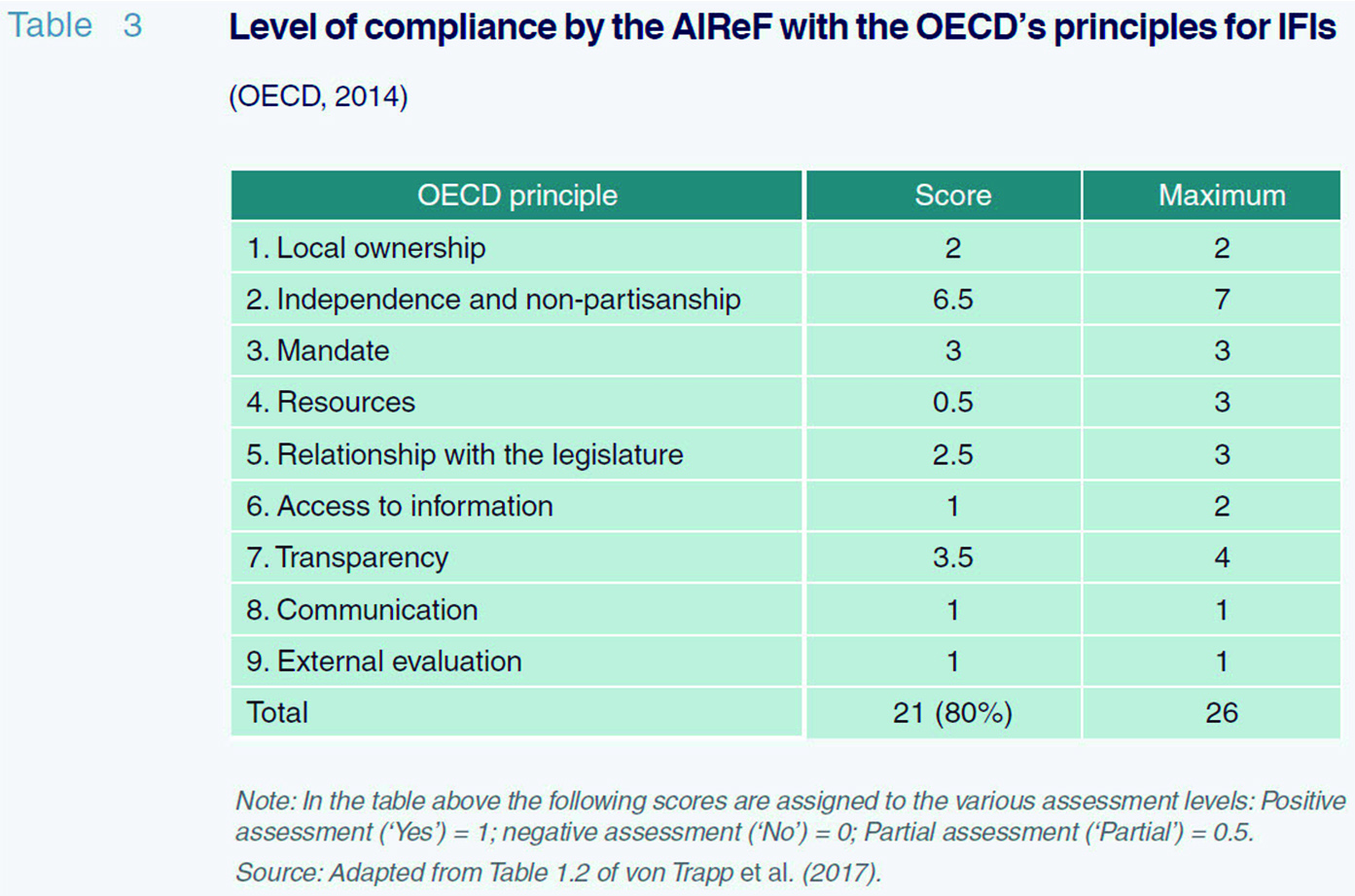

As for its structure, specifically the extent to which AIReF complies with the OECD’s principles for the creation of independent fiscal institutions (IFIs), the review scores of the AIReF are shown in Table 3. The AIReF’s level of compliance with the OECD’s criteria is essentially high (total in some instances) and only below 50% in the area of resources. In the case of resources, the reasons for the low score are threefold, according to the OECD: (a) AIReF’s already broad mandate is expanding with the risk of adding challenges to AIReF’s limited resources; (b) the Ministry of Finance makes changes in AIReF’s budget without consulting the agency; (c) there are no multiannual funding commitments, which might further enhance the independence of the AIReF.

Despite the AIReF’s strong start, the report flags three major challenges facing the institution:

- The difficulties encountered in terms of access to the information needed to do its job. The review recommends, in line with international best practice, governing the relationship between the AIReF and the Spanish government by means of a memorandum of understanding.

- The need to balance its ambitions and stakeholder demands for new work (or extending the scope of its existing duties) against its budgetary and staff constraints. The OECD recommends that the AIReF avoid taking on additional tasks unless it is given commensurate resources to undertake these tasks.

- Only around one half of the AIReF’s recommendations have been complied with. Indeed, the OECD report observes a significant difference in the pattern of responses by the central government relative to the sub-national (regional and local) governments. Whereas the central government opts to explain its non-compliance more often (62% of the recommendations received) than it chooses to comply (38%), at the sub-national government level, the pattern is exactly the opposite. Here is worth noting that compliance levels vary by region (Cantabria, Andalusia, Aragon, Castile and Leon and Valencia being more inclined to ‘comply’ and Madrid, Navarre and Catalonia being more inclined to ‘explain’). Refer to Figure 4.6 of the Review.

Beyond these key points, the Review makes 20 detailed recommendations grouped into four categories: inputs (6 recommendations); methodology and outputs (5); efforts at the sub-national level (3); and impact (6).

Regarding recommendations about inputs, the OECD suggests that AIReF “should avoid taking on additional tasks unless they are given commensurate resources to undertake these tasks with in-house staff” and that it “should use outside contractors sparingly”. The OECD recommends that the AIReF, the ministries and other relevant public administrations “work collaboratively to develop a memorandum of understanding on access to information, establishing which information AIReF need to fulfil its mandate and a mutually agreeable and collaborative process for information requests”.

In terms of methodology and outputs, the OECD report suggests that the AIReF could release projections for medium-term periods of three to five years; so far, the majority of AIReF documents are focused on the current and the upcoming year. It is also recommended that the AIReF releases more details about its economic and budgetary estimates and not only high-level summaries of the issues. Along the same lines, the OECD suggests the possibility that the AIReF examines the accuracy of its own projections and “whether there have been any significant biases in its own or the government’s forecasts”, as well as the possibility of analysing the reasons for these biases.

As far as subnational governments are concerned, the OECD recommends the AIReF “focus on improving the quality and deepening the reach of existing regional and local analysis”. In terms of impact, the OECD report contains the recommendation that the “AIReF should pursue a strategy of increased selectivity regarding its comply-or-explain recommendations with the aim of emphasising and focusing on its most important messages in subsequent dialogue with relevant administrations and in its public follow-up”. In this respect, the AIReF is also advised to “periodically undertake stakeholder satisfaction surveys for key stakeholders groups such as parliamentarians and academics”.

Conclusions

The AIReF in its first years in operation has helped to support progress on budget stability and enhanced fiscal governance in Spain and the EU by increasing the reputational costs of those public administrations which are not fiscally responsible.

Judging by the criteria used most commonly to assess the effectiveness of independent fiscal institutions, the AIReF is endowed with an institutional design and mandate that are in line with international best practice. In terms of its performance, in its early years it has established a reputation for independence from the Executive. When it has considered it necessary, the AIReF has taken different positions to those of the Ministry of Finance to which it is attached, prompting the latter to alter its initial stance on occasion. This independence provides a good foundation for reinforcing the fiscal framework in Spain and, by extension, the EU.

Beyond this procedural matter, the AIReF’s reports have highlighted two key matters of substance. Firstly, the need to find a better formulation, meaning a more user-friendly and effective one, of the spending rule stipulated in the 2012 Budget Stability Act. Secondly, the recommendation that the one-target-fits-all strategy applied to the regional governments should be revised.

Indeed, it can be said that the first steps taken by the AIReF have helped unearth some of the limitations of the 2012 Act and provided strong arguments in favour of its reform (Kasperskaya and Xifré, 2018). In this respect, our conclusions highlight the necessary complementarity among all elements (laws, institutions, political will) to achieve fiscal sustainability.

Lastly, the AIReF still faces noteworthy challenges, including accessing the necessary information to do its job, as well as maintaining the independence and professionalism that have characterised its conduct during the initial years. It would be advisable to think carefully before expanding the scope of its activities if it is not possible to guarantee the provision of sufficient resources. It would also be useful for the wider public if the AIReF released more details on the methodology and assumptions under which it prepares its own estimates and assesses budgetary projections by public administrations and reported on their activity in a timely and more user-friendly way.

That said, the reputational capital and credibility earned by the institution since 2013 are an important asset for the good of fiscal stability in Spain and the broader EU.

References

ANDRLE M.; BLUEDORN, J.; EYRAUD, L.; KINDA, T.; BROOKS, P. K.; SCHWARTZ, G., AND A. WEBER (2015), Reforming Fiscal Governance in the European Union. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/15/09.

BEETSMA, R., AND X. DEBRUN (2018),

Independent Fiscal Councils: Watchdogs or lapdogs? CEPR Press.

BÉNASSY-QUÉRÉ, A.; BRUNNERMEIER, M.; ENDERLEIN, H.; FARHI, E.; FRATZSCHER, M.; FUEST, C.; GOURINCHAS, P.-O. ; MARTIN, P.; PISANI-FERRY, J.; REY, H.; SCHNABEL, I.; VÉRON, N.; WEDER DI MAURO, B.; AND J. ZETTELMEYER (2018). “Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform”,

CEPR Policy Insight, No. 91.

CLAEYS, G. (2017), The missing pieces of the euro architecture,

Bruegel Policy Contribution, no. 28, October 2017.

CLAEYS, G.; DARVAS, A., AND Á. LEANDRO (2016), A propose to revive the European Fiscal Framework,

Bruegel Policy Contribution, no. 2016/07, March 2016.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2017), Country Annex Spain to the Report from the Commission Presented under Article 8 of the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union.

HERNÁNDEZ DE COS, P., AND J. J. PÉREZ (2013), “The New Budgetary Stability Law”,

Economic Bulletin of the Bank of Spain, April: 65 - 78.

JONES, E. (2018), “European economic governance reform: Moving past power politics”,

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, vol 7.1: 65 – 76.

JUNCKER, J.C.; TUSK, D.; DIJSSELBLOEM, J.; DRAGHI, M., AND M. SCHULZ (2015), “The Five Presidents’ Report: Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union”, 22 June.

KASPERSKAYA, Y., AND R. XIFRÉ (2018), Reform or Resist? The tale of two fiscal reforms in Spain after the crisis,

Public Money & Management, upcoming publication.

MANESSE, P. (2014), “Time to scrap the Stability and Growth Pact”,

VOXEU, retrieved from

http://www.voxeu.org/article/time-scrap-stability-and-growth-pactSPANISH MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND CIVIL SERVICE (MINHAFP) (2017), Review of the regulatory impact of the Royal Decree amending Royal Decree 215/2014 enacting the organic statute governing the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIReF).

http://www.minhafp.gob.es/Documentacion/Publico/NormativaDoctrina/Proyectos/170620%20Memoria.pdfOECD (2014),

OECD Principles for Independent Fiscal Institutions, http://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/recommendation-on-principles-for-independent-fiscal-institutions.htmTRAPP, L. V.; NICOL, S.; FONTAINE, P.; LAGO-PEÑAS, S., AND W. SUYKER (2017),

OECD Review of the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIReF) OECD.

WOLFF, G. (2017), “Beyond the Juncker and Schäuble Visions of Euro-Area Governance”,

Bruegel Policy Brief, no. 6, December 2017.

Yulia Kasperskaya. Business Department, Universitat de Barcelona

Ramon Xifré. ESCI-UPF School of International Studies and the Public-Private Sector Centre at IESE Business School