The Autonomous Regions’ funding model: Between the State and the markets

In 2016, the State and some of the Autonomous Regions have been able to take advantage of favourable market conditions to improve their public debt dynamics – reducing servicing costs and extending maturities. Going forward, the government would be prudent to focus on transitioning the regions away from reliance on the State towards reliance on capital markets to meet their financing needs.

Abstract: The large increase in the overall stock of public debt as a result of the crisis has raised Spanish debt to GDP levels from below 40% to just slightly above 100%. Nevertheless, benign market conditions in 2016 allowed both the State and some Autonomous Regions to tap debt markets on very favourable terms, which resulted in an increase in the average life of their portfolios and a reduction in average costs. For 2017, the State is expected to continue to cover the bulk of its financing needs through the issuance of long-term debt. However, at the regional level, the majority of financing is still provided by the State through the special liquidity mechanism. Regional bond issuance has increased with financing conditions having also improved, but the government should take advantage of the current climate to increase financial autonomy for those regions that have still been unable to return to capital markets. Doing so may help the government address other more urgent issues – such as the near depletion of the Social Security Reserve Fund – that may require, at least in the short-term, additional debt issuance.

Public debt will tend to stabilise at around 100% of GDP

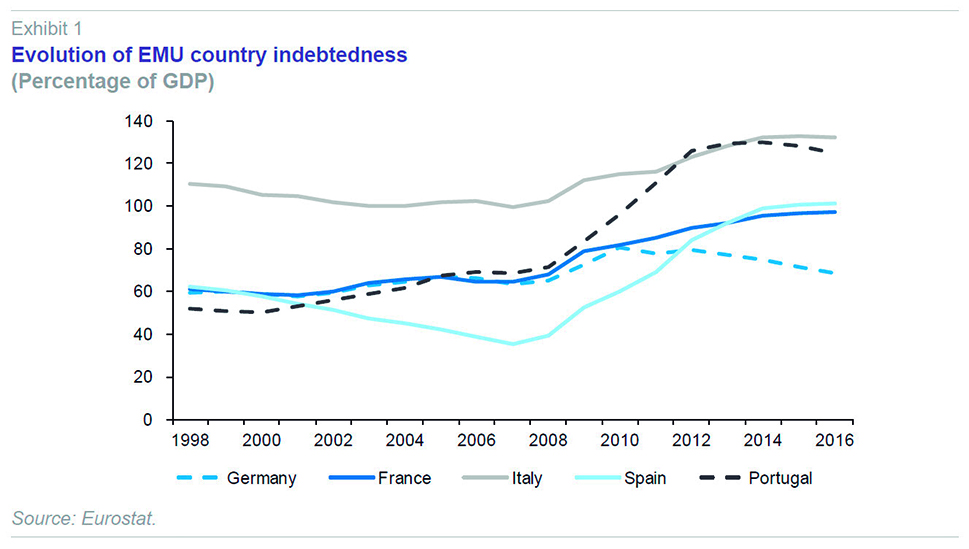

Spanish public debt stood at below 40% of GDP before the outbreak of the financial crisis, a level that was well below other countries such as Germany, France and Italy. However, the strong recession suffered by the Spanish economy resulted in a sharp deterioration in fiscal revenues, at the same time as spending grew substantially due to a variety of factors (unemployment benefits, support to the financial system, increase in interest expenses, etc.). All of this resulted in a series of large deficits in an environment of weak growth, which has meant that in less than a decade the public debt ratio has increased by more than 60 percentage points and is currently at the same levels as that of France and well above that of Germany.

Although Spain has exited the crisis robustly and is the quickest growing amongst the big four Eurozone economies, it has yet to fully correct outstanding fiscal imbalances, which in turn prevent it from entering into a debt reduction path.

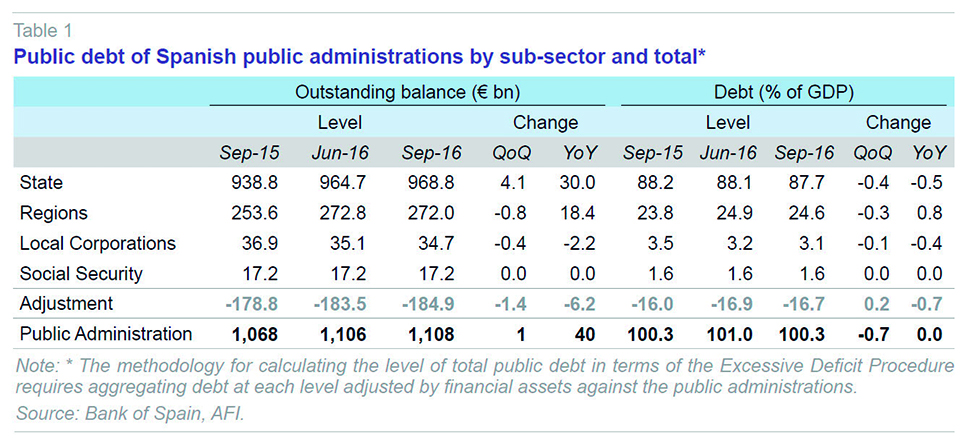

As a result, at the end of the third quarter of 2016, public debt stood at 1.11 trillion euros, having increased in the last twelve months by around 40 billion euros. The combined Public Administrations closed the year with a debt-to-GDP ratio of slightly above 100% – at 100.3% in September. Despite the growth in debt in absolute terms, dynamic growth has helped to neutralise the increase in relative debt in GDP terms, which has remained practically stable compared to last year. Even so, it is worth emphasising that the debt ratio will be one percentage point higher than predicted by the government at the end of 2016, which forecast 99.4% in its 2017 Budget Plan.

Although debt fell by 0.7 percentage points in the third quarter of 2016, we do not expect this trend to be maintained in the coming quarters, given that this reduction was more the result of context-specific developments as opposed to underlying debt dynamics. In the best case scenario, and in the absence of a more effective deficit reduction strategy, it is likely that debt will remain close to current levels (2016: 100.6%; 2017: 100.8% and 2018: 100.4%).

The breakdown of total debt levels leaves the State with debt equivalent to 87.7% of GDP, the Autonomous Regions with debt worth 24.6% of GDP, the Local Corporations (CCLL in their Spanish initials) with debt of 3.1% of GDP and the Social Security Administration with debt of 1.6% of GDP. Debt adjustments between the different administrations mean that the total is less than the sum of the sub-sectors. Of this 185 billion euros adjustment, practically all of it is debt owed by the regions to the State through the Fund for Financing Autonomous Regions – 138 billion euros – and some residual debt captured through the Financing Fund for the CCLL – 7.2 billion euros. The rest is explained by Treasury debt acquired by the Social Security Reserve Fund. These acquisitions are declining, and in the absence of additional measures, the Fund could be exhausted by the end of this year or, at the latest, by the start of 2018.

Record lows in Treasury financing costs and increase in average life of the debt portfolio

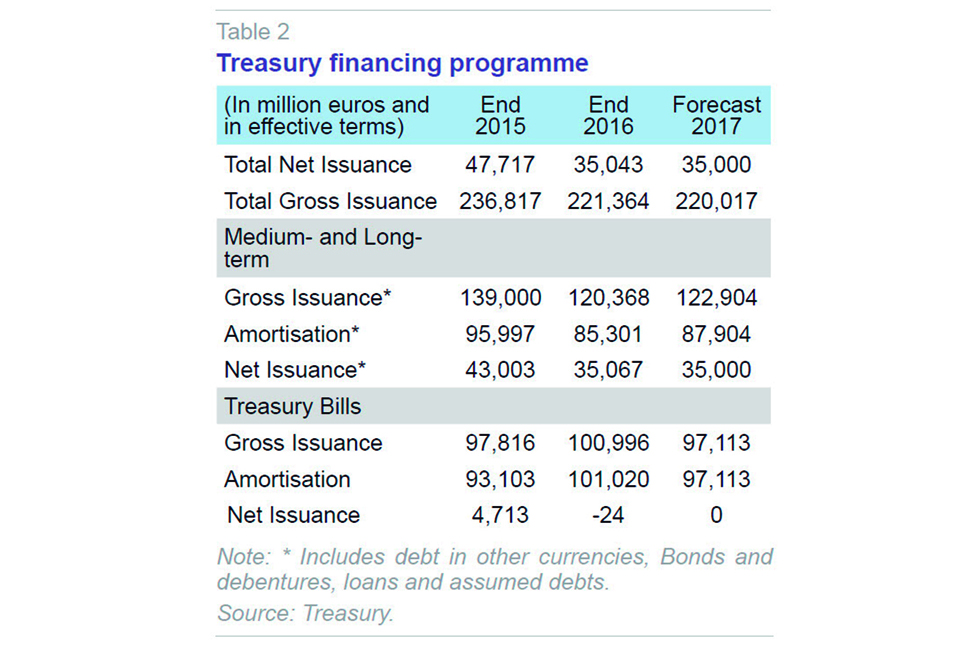

The Treasury’s gross financing needs in 2016 amounted to 221 billion euros. 120 billion euros was covered through issuance of bonds and debentures and 101 billion euros through Treasury bills. The bulk of these needs were directed towards refinancing maturities. New issuance amounted to 35 billion euros, slightly below the 45 billion euros initially planned.

The strategy envisaged for 2017 is very similar to 2016 with total issuance of 220 billion euros and net issuance of 35 billion euros, which will be financed entirely through issuance of bonds and debentures. This net debt issuance will not only go to financing the State’s deficit, given that a significant part of the debt taken on by the Treasury is used to channel liquidity to the regions, who acquire debt obligations with the State through the Financing Funding for the Autonomous Regions (FFCA).

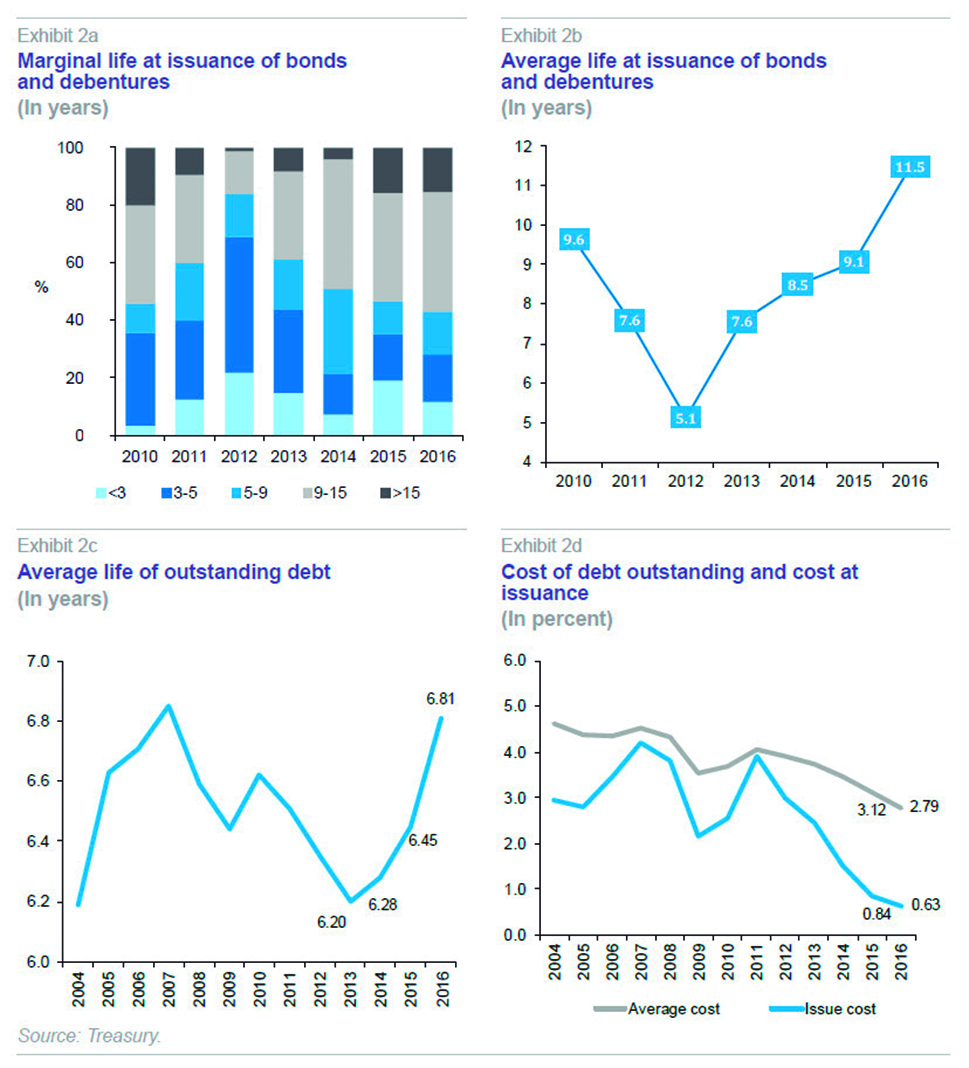

In spite of having to issue large quantities of debt, the Treasury has done so under clearly favourable conditions and it has been able to take advantage of new record low interest rates to finance new debt. The Treasury has benefitted from the clear downward trend in average yields, from a 3.8% average yield on debt issued at the end of 2011 to 0.63% at the end of 2016. As a result, the average annual cost of the Treasury’s debt portfolio has fallen from 4.1% to 2.8% in 2016.

This relative reduction in the cost of debt is a result both of the drastic reduction in the risk premium on Spanish debt relative to German debt, as well as a lowering of the underlying interest rate at which the German treasury finances itself. Both movements are explained to a large degree by the expansive monetary policy adopted by the ECB. Although the strong performance of the Spanish economy and the clean-up of the banking sector has also played an important role in reducing the risk premium.

As has been the case for neighbouring countries, the Treasury has taken advantage of current economic and financial conditions to lengthen the average life of its portfolio. This will help prevent future bouts of financial tension from creating difficulties in placing debt on the markets, given that fewer maturities will accumulate in a given year. As such the average life has increased from 6.2 years at close of 2013 to 6.8 years at the end of 2016. In fact, among all the Treasury’s long-term debt issues last year, more than 50% had a maturity of equal to or more than 10 years, a proportion that is well above previous years. Furthermore, 16% of the total has been issued with a maturity of more than 15 years, with even a 50-year issuance being offered through a syndicated operation half way through the year, which had a clear market signalling effect.

In 2017, the Treasury will continue with its strategy of covering the bulk of financing needs with long-term issues through ordinary fixed coupon bond and debenture auctions. Although, as was the case in 2016, it could hold some benchmark auctions indexed to European inflation in the first auction of each month. This type of debt now exceeds 3% of total State debt in circulation. Similarly, on specific occasions, the Treasury may well make use of bank syndications to place certain benchmarks.

Increased regional recourse to the markets despite the increase in the FLA

The support from markets and the continuation of Treasury liquidity mechanisms through the Financing Fund for the Autonomous Regions (FFCA)

[1] have lent support to regional governments’ debt strategies. The majority of financing needs in 2016, approximately two-thirds of the total, have been covered by recourse to the Treasury, which has provided 31.3 billion euros to regions that have voluntarily requested liquidity. The incentives provided by the State for regions to reduce their presence in the market makes it difficult for some regions to justify seeking financial autonomy. Although it is true that the most indebted regions have no other alternative, in other cases, the choice to remain in the FFCA is explained by the subsidy being offered by the government in financing the regions. Not only because it is not applying any cost for managing or intermediating this financing but also because it has offered 0% interest rates during the first three years to all regions that have complied with budgetary stability through the Financial Facility compartment.

However, although issuance activity for regional debt continues to be reduced in comparison to potential issuance, market conditions have also been very favourable with interest rates at record lows and even closing in on Treasury financing costs. In fact, in 2016 three more regions (Asturias, Castille and Leon, and La Rioja) joined the three regions already financing themselves on the markets last year (Basque Country, Navarre and Madrid). Although they have had a (diminishing) spread over the Treasury, this strategy allows them to benefit from lower future costs, achieving the status of regular issuers with a permanent investor communications policy.

There are also several additional factors that may impinge on each regional government’s decision. Some of them are political, relating to the loss of financial autonomy associated with adhering to the Autonomous Liquidity Fund (FLA in its Spanish initials), or being subject to a variety of conditions. Other factors relate to the market, given that financing provided by the FLA is conditioned by very standardised maturities – until now, ten years, making it impossible to take advantage of opportunities to lengthen maturities in the current low interest rate environment, as the Treasury itself is doing.

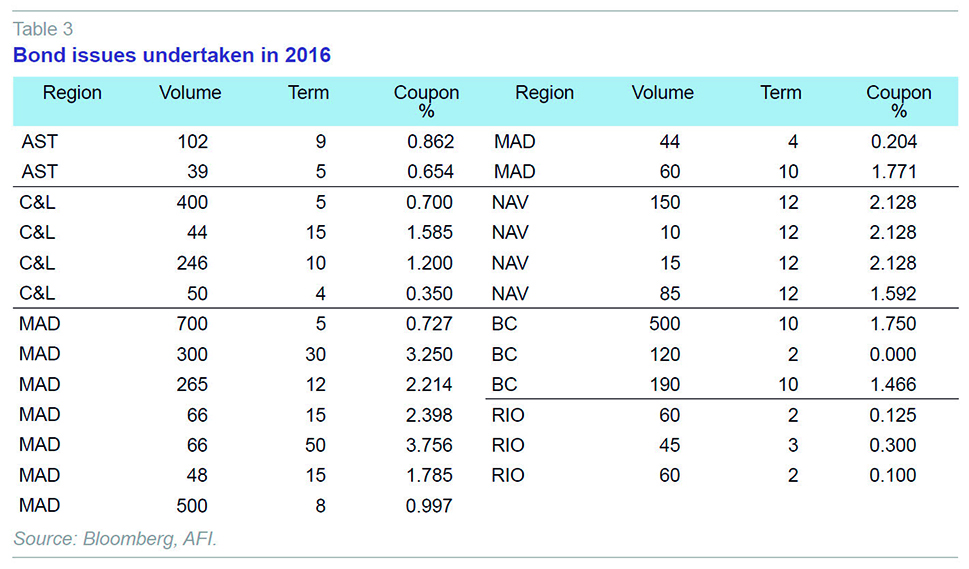

The return of some regions to the capital markets has logically had an impact on regional bond markets. Although overall volumes issued have not been very significant (rising from 3.5 billion euros in 2015 to 4.2 billion euros), the increase in the number of issues has been more notable. While only nine issues of regional debt took place in 2015, in 2016 the number of issues increased to twenty-five.

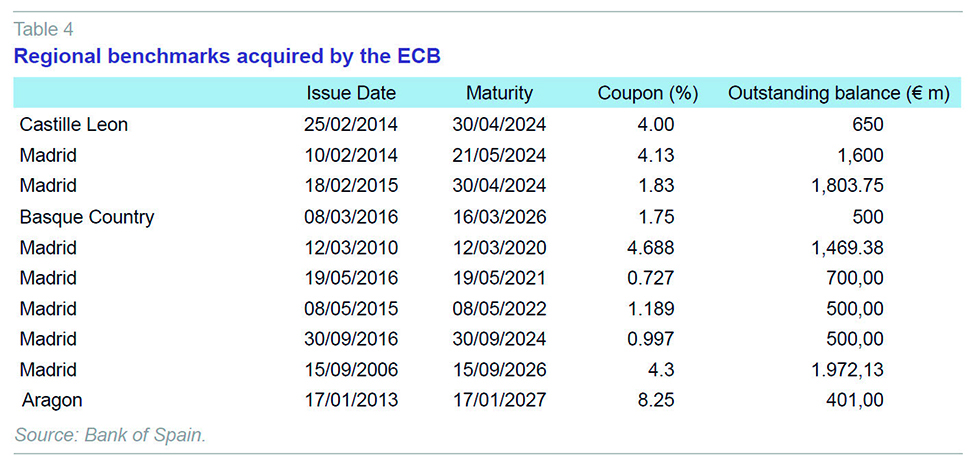

The regions that decided to tap the markets in 2016 covered their financing needs under very favourable conditions with ample liquidity, reflecting a combination of reduced supply of regional securities with significant demand from investors seeking additional return over sovereign debt. Also, it is important to underline the ECB’s decision to include sub-sovereign debt within its public debt buying programme, the Public Sector Purchase Programme. Although there are relatively few liquid benchmarks in the regional debt market, by the end of 2016 the ECB had already acquired debt from ten different issues relating to four regions ‒ Madrid, Castille and Leon, Basque Country and Aragon. Seven of these issues belong to the Madrid region, which represents an endorsement for regional governments which develop a strategy based on active market involvement with issues focused on volumes at the most desirable maturities and which can serve as a benchmark for the sector.

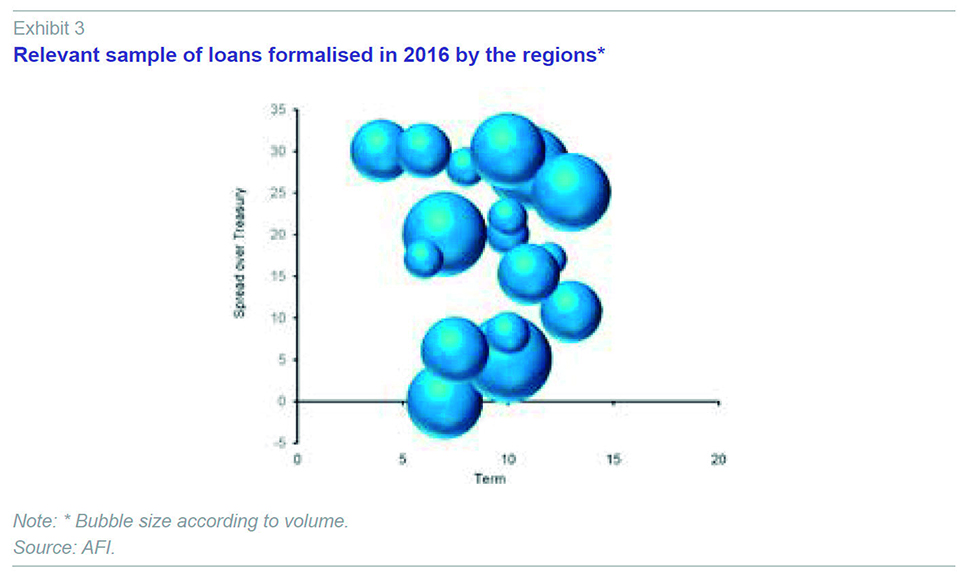

The regions also channelled an important amount of their financing needs through loans. In some cases achieving financing conditions that have been as advantageous or even better than securities issues. The maximum spread that regions can accept for bank loans has been subject to government limits since September 2012, through the so called Financial Prudence Principle. Even so, it is worth highlighting that in the majority of cases the market has been below the regulatory established limit. And it is not just regions outside of the FFCA that have taken out loans. Some of the regions participating in the mechanism have continued to refinance their portfolios with the aim of reducing average costs and generating savings, taking advantage of the banking sector’s desire to gain market share. Though it has to be said that the results have been rather mixed for different regions. The reopening of this market has been led by small and medium-sized banks, while larger banks continue to be dissatisfied with the way in which the Financial Prudence Principle restricts their margins on refinancing operations.

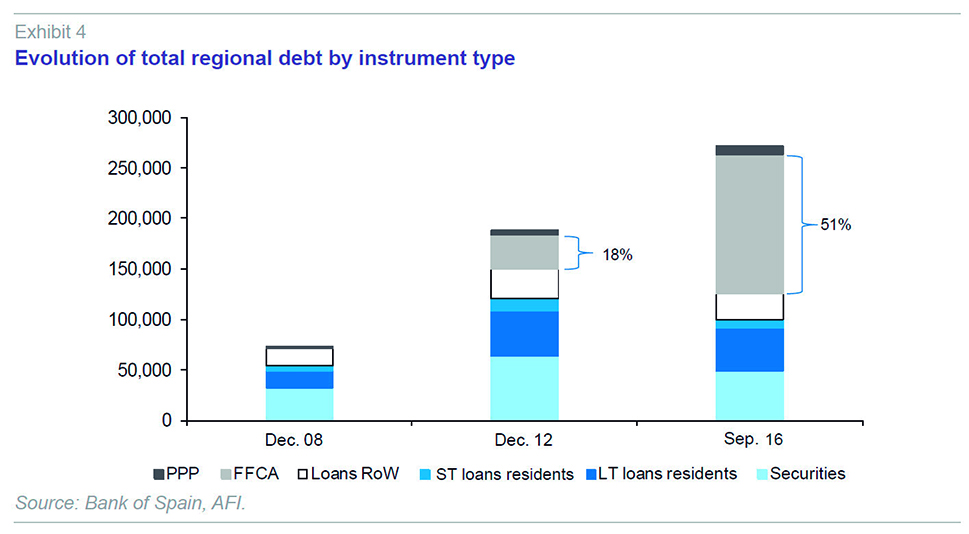

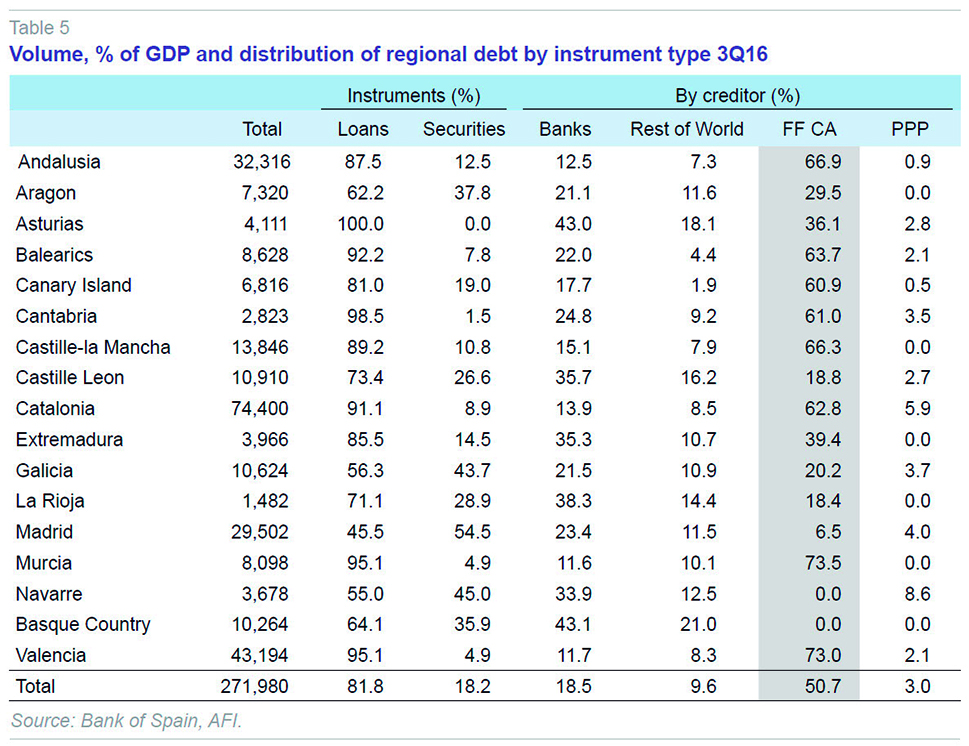

Nonetheless, the overriding development over the last five years has been the lead role that the State has adopted as financier-in-chief for the regional governments. More than 50% of regional debt is now owed to the State. Without doubt, this development will be key in the immediate short-run, especially with the anticipated reform of the regional financing system. These circumstances have affected the structure of regional debt portfolios, which logically has had a knock-on impact on other financiers and instruments. Even so, the fact that some regions have decided to finance themselves on capital markets in 2016 has meant that the weight of securities in total financing has remained around 18%. Loans from national banks represent a similar proportion, meanwhile the remaining 10% of financing is primarily owed to foreign banks.

The distribution of debt is relatively disparate between different regions, both in relative terms and in regard to the instruments used. In terms of the debt-to-GDP ratio, only five regions are above the regional average (24.6%). Two of them, Catalonia and the Valencian Community, account for 43% of total regional indebtedness, with very high debt ratios (of 35.6% and 41.6% of GDP, respectively). The regions with the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio are Madrid (14.2%), Basque Country (15.2%) and the Canary Islands (15.8%), with five other regions with debt levels below 20% of GDP. These are the regions with readiest access to capital markets.

There is also an important degree of divergence in terms of the instruments used. While regions such as Navarre and the Basque Country have never accumulated debt obligations against the FFCA, and Madrid only during one year, eight regions owe more than 60% of their debt to the FFCA or even close to 75% in the case of the Region of Murcia and the Valencian Community. Inevitably, participation in these mechanisms reduces the weight of securities issues, such that regions which have traditionally had a significant presence in bond markets, such as Catalonia, Andalusia and the Valencian Community, now only have residual recourse to this type of financing.

Conclusions

A wide variety of factors have helped Spain’s public administrations to cover their financing needs at increasingly lower costs, especially the Treasury and Autonomous Regions.

[2] Despite the major increase in public debt, dynamic economic growth and improvements in domestic fundamentals explain a large part of renewed investor confidence. This is less true for compliance with deficit targets, which have been missed on a systematic basis.

But above all, external factors, bracketed by the ECB’s exceptionally accommodative monetary policy, have driven yield curves down to record lows throughout nearly the whole Eurozone with negative benchmarks in nearly all representative German debt tranches. This has meant that the Treasury has not only been able to meet its own financing needs, but also intermediate two-thirds of regions’ financing needs, over-indebting itself to the tune of 140 billion euros since 2012.

All of this has been possible because the ECB has acquired more than 90 billion euros on secondary markets in 2016 alone, an amount equivalent to three-quarters of the Treasury’s gross issuance of bonds and debentures and tripling last year’s net financing needs.

However, this strategy is not risk-free for the State. Although from an accounting perspective the debt is imputed to the regions, the issue activity belongs to the Treasury, which has had to devote 40% of net issuance to financing the different FFCA compartments in the last five years. Clearly the yield curve cannot be immune to this increase in debt stock, which amounts to around 15% of the outstanding balance. Even if the impact has been minimal, it is unlikely to remain so in the future.

When it was originally set up, the financing mechanism helped to fend off the danger of a regional government defaulting and injected liquidity into the economy, but in the current environment it is doubtful whether the Treasury needs to continue providing incentives for this type of financing and thus dissuading regions that would be potentially able to access the market through interest rate subsidies. Unless the idea is for this to become permanent policy, which would raise questions in terms of its impact on regional financial autonomy, driving investors away from regions for a long period of time will imply increased re-entry costs, which could be avoidable. Leaving to one side other issues, such as the perverse incentives created by the current system for budgetary stability and the degree of discretion and asymmetries involved in the current distribution of resources, the problem of regional financing cannot be dealt with solely by resolving indebtedness. The current climate allows the regions to return to the markets and the Treasury should focus on helping those regions that have still been unable to do so, whilst at the same time defining a model that ensures sufficient financing, in line with the principles of fairness, transparency and joint fiscal responsibility, as reflected in the draft of the Regional Presidents’ Conference.

It is clear that the benign external environment will not remain like this forever and the Treasury is now responsible for managing a record debt portfolio of around one trillion Euros, attempting to minimise costs to the taxpayer. In a State as decentralised as Spain, the different administrations should assume collective fiscal responsibility. Limiting autonomy through the financial route does not seem to be particularly prudent if it comes at the cost of over-indebtedness which undoubtedly limits the Treasury’s ability to access the markets. Even more so when there are other urgent issues to resolve which will involve, at least in the short-term, increasing debt. In fact, with the Social Security Reserve Fund nearly depleted, the most important and urgent structural imbalance in our public accounts is undoubtedly financing the pensions system. Although this can partly be addressed through increasing revenues, it is difficult to see how this can be done without measures that involve recourse to debt.

Notes

The Financing Fund for the Autonomous Regions is divided into four compartments: Financial Facility, Autonomous Liquidity Fund (FLA), Social Fund and Payment Providers Fund (FFPP). Nonetheless, in 2016, funding needs have only been covered through the first two funds and this is expected to remain the case in the coming years.

In contrast to the State and the regions, since June 2012 Local Corporations have been immersed in a deleveraging process, reducing their debt levels by 12 billion euros to 34.7 billion euros in September 2016. This is equivalent to a 25% reduction from the peak registered in mid-2012. This debt reduction has come about to a large degree as a result of regulatory limitations placed on their ability to take on debt.

César Cantalapiedra and Salvador Jiménez. A.F.I. -Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.