Outlook for the Spanish financial sector ahead of Brexit

Uncertainties surrounding Brexit and its upcoming implementation are expected to bring a series of challenges for Spain – a country with strong economic and financial ties to the UK, in particular as regards its banking sector. Spanish banks are expected to be well prepared to weather the upcoming changes, some of which may also present opportunities to attract additional business to Spain.

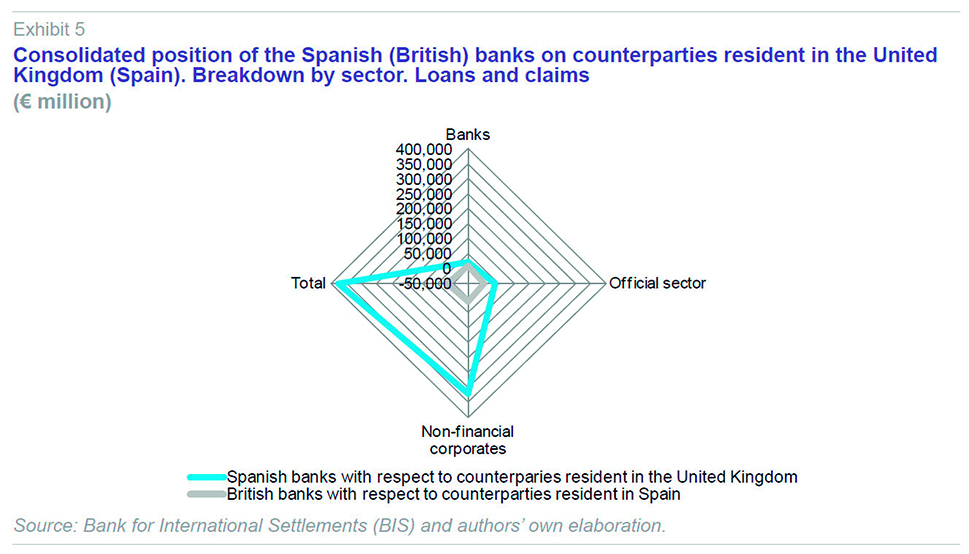

Abstract: The UK’s exit from the EU, or Brexit, was one of the big surprises on the economic front in 2016, with Brexit implementation set to be one of the major challenges for 2017. Spain has considerable economic and financial ties to the UK, specifically as regards its banking sector – both direct investment and exposure in terms of credit and claims held by Spanish financial institutions in the UK are very substantial. Direct investment in the UK by Spain’s financial sector stands at over 16 billion euros. Spanish banks’ exposure to the UK is high: claims totalled 377.29 billion euros as of June 2016, made up of 18.6 billion euros of claims on banks, 38.51 billion euros on the official sector and 320.19 billion euros on non-financial corporates (mainly in the form of loans and equity investments). The triggering of Brexit and its implementation is expected to bring about a host of scenarios and challenges. However, we expect Spanish banks with economic interests in the UK to be prepared to affront these challenges, in part due to the preservation of the EU passport (as they will probably maintain their main headquarters in EU territory and keep their business in the UK through subsidiaries), as well as their experience with international diversification. At the same time, Spanish regulators and government authorities are also taking steps for Spain to potentially benefit from some of the expected changes anticipated from Brexit, specifically as regards the possible relocation of European regulators or institutions.

Economic estimates conditioned by political scenarios

This article attempts to analyse the state of the Spanish financial sector ahead of the UK’s exit from the European Union in 2017, or Brexit. Although it tries to focus on the economic aspects and, above all, the financial dimension, it is virtually impossible not to refer to the political arena. The main reason is the fact that an economic assessment of the consequences of Brexit is contingent upon political scenarios, as assumptions regarding the possible negotiations and the level of ‘tension’ surrounding them are crucial to evaluating the potential impact on the economy and financial sector.

It is probably fair to say that the time for referring to Brexit as an unexpected development has come and gone. The triggering of article 50 of the EU Treaty to enable the UK’s exit looks set for March. There are reasons enough to believe that the negotiations could be surrounded by a certain amount of tension and perhaps even improvisation which could similarly have economic and financial consequences. For example, at the time of preparing this paper for publication in early January, it was announced that Ivan Rogers, Britain’s Permanent Representative to the EU, had resigned, a development the vast majority of analysts have interpreted as indicative of a lack of strategic consensus in the UK.

It is also worth highlighting the role that the British Parliament could have in triggering the EU’s exit. The British government has finally confirmed the Parliament will in the end have a say on the terms of Brexit. UK Prime Minister Theresa May has assured that, although she has also said there will be a ‘clean exit’ from the EU Single Market.

In fact, the British government appears to be preparing for the political debate on what is already being dubbed the ‘Great Repeal Bill’, legislation which addresses multiple aspects of the existing and future relationship with the European Union.

From the economic standpoint, the key appears to be what may or may not be decided at the time of departure. It is assumed that, unless the parties agree otherwise, the negotiation process will take two years. In fact, Theresa May has insisted that her government does not intend to extend the period of negotiation that will follow the triggering of article 50 of the EU Treaty, albeit adding that “it may be the case that there are some practical aspects that require a period of implementation thereafter.” She has said some elements of the process may indeed need further discussion and negotiation beyond 2019.

Accordingly, scenario analysis for evaluating the economic fallout from Brexit can be based on two quasi-certainties that are beginning to take shape: The exit will be triggered in March 2017 and there will be an “implementation phase”. This implementation phase implies a negotiation period which in reality could stretch substantially beyond the official two-year deadline. Seemingly less-complex precedents such as the free trade treaties with the US and Canada are good examples of how time is the one thing these sorts of agreements require.

To attempt to assess the potential extension of the negotiations in time it is not only useful to analyse the public position taken by the parties (the United Kingdom and the EU) (which, for that matter, have been notable for their lack of specificity to date), but it is also important to factor in the position of the business sectors which stand to be affected, particularly in the UK. Multiple surveys have been carried out in this respect and the stances reflected have almost always coincided.

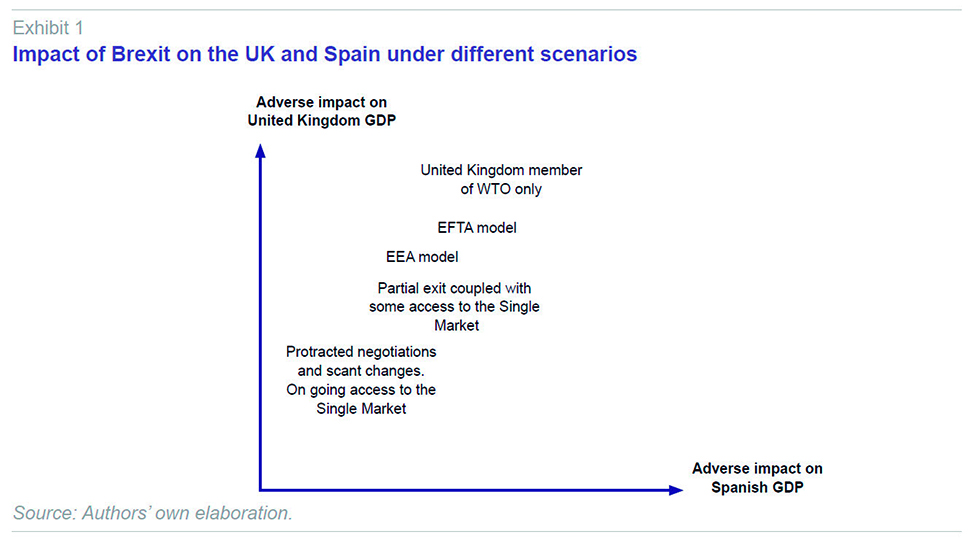

Exhibit 1 assesses the potential economic consequences of Brexit in the UK and Spain by examining the relative impact of Britain’s departure from the EU for both countries as a function of the ultimate political scenario, albeit without factoring in the possible probabilities of each. The aforementioned “Breturn” scenario is not contemplated in the Exhibit as the only possibility of returning to the initial situation would have to take the form of some sort of lawsuit with respect to the legality of the entire process within the UK, a process that would be protracted and costly in terms of uncertainty and red tape. Regardless, it could be considered largely akin to the scenario defined in the exhibit as “Protracted negotiations and scant changes. Ongoing access to the Single Market”. We believe that this situation would have limited costs for Spain (little beyond the impacts observed since the referendum) but higher costs for the United Kingdom by undoing an administrative and political process which has already, de facto, altered many expectations and institutional structures in Great Britain, while failing to resolve the social division caused by existing relations with the EU.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is an exit that would leave the UK as just another member of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), which would imply abandoning the Single Market with significant costs for members such as Spain, albeit ultimately higher costs for Great Britain itself. There are two other situations often discussed which are similar to this one. One relates to an agreement similar to that to which Norway is party within the European Economic Area (EEA), which includes access to the Single Market but without sharing the EU’s political structures. The other is a model similar to Switzerland’s, within the European Free Trade Area (EFTA), which is similar to the EEA but does not require contributions to the Single Market’s budget.

Estimating the impact and the role of the implementation phase: The role of the financial sector

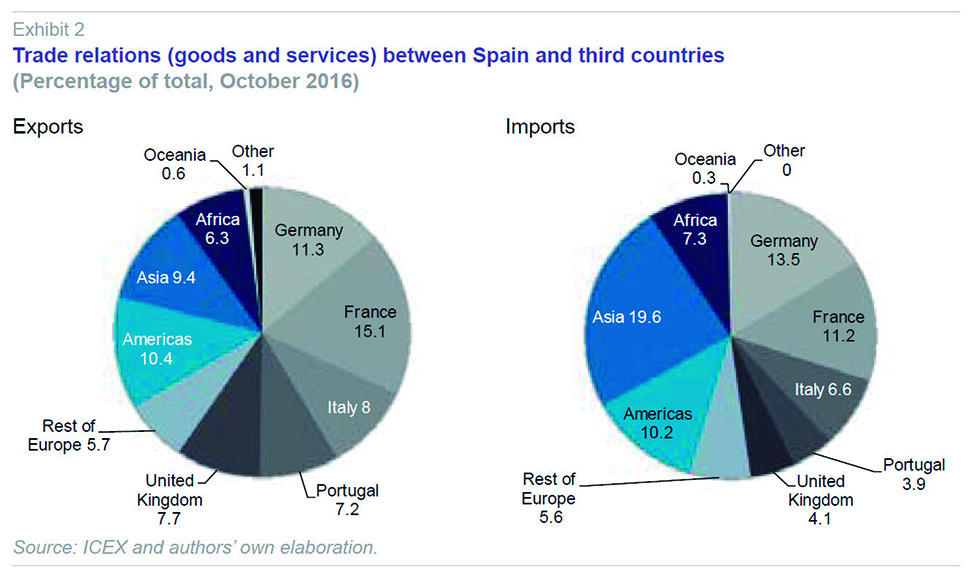

By not quantifying the impacts, Exhibit 1 can be considered a set of starting assumptions. At anyrate, the impact of the various scenarios will change depending on how smoothly the negotiations go and whether they play out more or less in the business and financial interests of Spain, which has very significant ties with the United Kingdom. Using data published by the ICEX (Spain’s foreign trade institute), we note that the Spanish economy had a trade surplus with the UK equivalent to 1.3% of GDP as of October 2016. Importantly, the UK is one of the few countries with which Spain has a trade surplus in both goods and services. Some 7.7% of Spanish exports go to the UK, where it sells a wide range of goods and services. Some of the most important goods and services include cars, trains, aviation assets, fruit, vegetables and, of course, tourism. According to the Spanish statistics bureau’s cross-border movement numbers (INE-Frontur), 17 million people visited Spain from the UK between January and November 2016, which was 12.3% more than in the same period of 2015 and 21.1% of all foreign arrivals. Beyond the official records, it is estimated that between 800,000 and 1,000,000 Britons are living in Spain either permanently or for long spells each year. The official figures only show those who have registered as residents, a number that stands at 250,000. From the financial perspective, it is worth noting that the majority of visitors and residents are over 65 years of age, such that pensions, money wires, healthcare and real estate transactions are very important considerations for them in the context of Brexit.

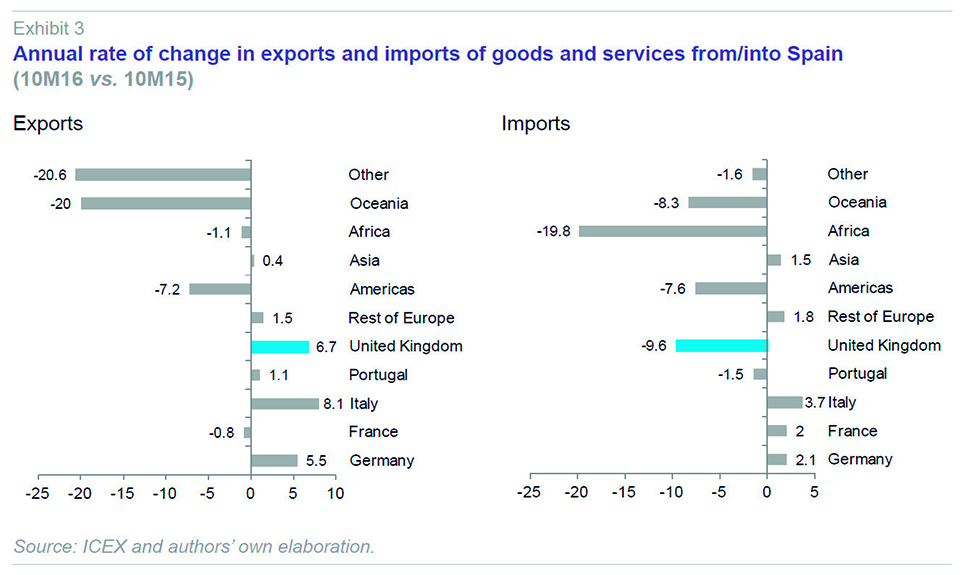

What the ICEX figures appear to show is that the June 2016 referendum in favour of Brexit has not, to date, had an adverse impact on trade relations between the two countries, at least from the Spanish standpoint. The United Kingdom accounted for 9% of all Spanish exports (goods and services) between January and October 2016 and 5% of all imports. As shown in Exhibit 3, exports to Great Britain increased by 6.7% year-on-year between January and October 2016, while imports contracted by 9.6%. This suggests that Brexit has not dented the trade surplus, at least not in the short term.

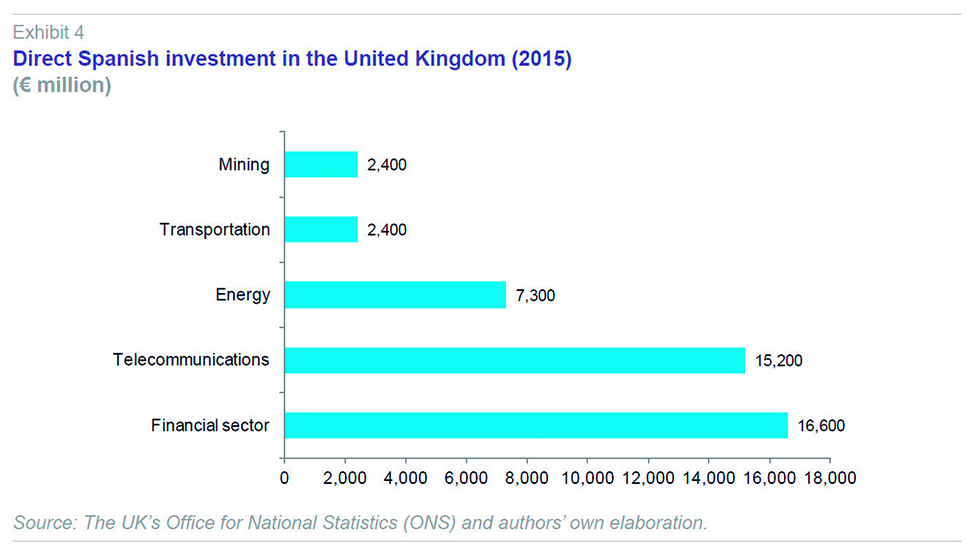

What about the financial sector? One good way of sizing up the Spanish financial sector’s exposure to the UK is to look at direct Spanish investment using the UK’s Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) figures. The ONS’ most recent annual numbers date to 2015 (Exhibit 4) and show that indeed the financial sector is the biggest direct investor, having invested 16.6 billion euros, followed by the telecommunications sector (at 15.2 billion euros) and the energy sector (7.3 billion euros).

An even better snapshot of the scale of financial relations can be gleaned from the consolidated banking statistics compiled by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

Exhibit 5 shows the consolidated position of the Spanish (British) banks on counterparties resident in the United Kingdom (Spain). The numbers track the claims (loans and other claims) held by the banks of each country on the various sectors in the other country, including other banks, the official sector (public debt and similar interests) and the non-financial corporate sector. The claims are shown on an ultimate risk basis, which means net of the risk transfers these banks may make between counterparties. As shown in the exhibit, Spanish banks’ exposure to the UK is high: claims totalled 377.29 billion euros as of June 2016, made up of 18.6 billion euros of claims on banks, 38.51 billion euros on the official sector (government and other public institutions) and 320.19 billion euros on non-financial corporates (mainly in the form of loans and equity investments).

However, the consolidated claims held by the British banks located in Spanish territory are considerably smaller, at 20.17 billion euros, held mainly on banks (8.11 billion euros) and corporates (12.37 billion euros); claims on the official sector are actually negative on a net basis (-289 million euros).

In addition to the sheer scale of the numbers, there are several other dimensions which render the Spanish banks’ exposure to the UK even more significant. The Spanish banks command a meaningful share of the British retail banking market, having acquired the assets of troubled financial institutions in Great Britain during and after the financial crisis, among other things. As a result, the British economy’s recovery in the years following the crisis has had a positive impact on the Spanish banks’ earnings diversification. In contrast, any Brexit-driven adverse impact on the economy in the medium term – for example, a higher unemployment rate – will similarly have negative consequences.

One unknown with multiple ramifications relates to potential changes in financial regulations. The world over, the banks are facing the final provisions required to fully implement the Basel III capital framework in 2019. In parallel, pressure to increase transparency is growing with the recent announcement of new stress tests coordinated by the European Banking Authority and the European Central Bank in 2017. And, last but by no means least, the sector faces the added difficulty of the banking crisis unfolding in Italy, which has just led to the bail out of Monte dei Paschi di Siena and setting aside of up to 20 billion euros to cover the rest of the sector’s potential capital requirements. Against this backdrop, financial relations between London and Europe may be affected by additional contingencies thrown into the negotiation process. The ECB itself has even suggested that some of the most important discount window trades carried out by eurozone banks through the London Clearing House (LCH Clearnet) to obtain liquidity could ultimately be performed by other eurozone clearing houses. Rumours have also proliferated about the possibility of UK banks establishing operations in other European markets in order to preserve their access to the EU’s single market. In sum, there are a host of possibilities foreshadowing major potential structural changes in the competitive landscape and/or regulatory framework.

For the Spanish banks which operate on a consolidated basis from Spain, the diversification opportunity will continue to exist, given that their ability to use the single European passport is not at risk as far as the parent company maintains its license in an EU country. Nevertheless, they need to watch for any change or requirement which could emerge in the UK for these banks.

The upside

Nevertheless, the tumultuous regulatory and competitive landscape which Brexit may bring about for the financial sector also brings opportunities. The official institutions have taken note and are acting accordingly.

Spain’s securities market regulator, the CNMV, in concert with the Spanish government, has drawn up a plan for leveraging the opportunities Brexit is expected to generate on the financial front. Its plan is designed to attract the financial institutions which may be contemplating switching their head offices to the EU and specifically to Spain. These measures were announced on December 12

th and are accompanied by a dialogue in English and create a pre-authorisation process so that firms can analyse the move as fast as possible – the CNMV is offering several regulatory benefits.

[1] The plan is articulated around five points:

- Creation of a welcome package targeted specifically at investment and management companies headquartered in the UK. Within this programme, interested companies will benefit from a single point of contact, in English, who will help them understand Spanish regulations and guide them through the entire permission process until six months after authorisation is obtained.

- A direct authorisation procedure for companies headquartered in the United Kingdom. Standardised forms in English and facilitation of electronic submission thereof. Establishment of a pre-authorisation deadline so that companies can begin to organise moving their businesses to Spain.

- Use of internal minimum capital calculation models: This measure comes in response to the interest expressed by some entities in being able to continue to use their internal models for calculating the capital they need to set aside to cover their market and counterparty risks. The CNMV aims to ready itself to supervise those models directly. To this end, a specific regime for cooperating with the Bank of Spain has been set up to ensure that this effort proceeds smoothly. There is also scope for availing of a rapid authorisation procedure to the extent that the competent authority in the United Kingdom has reviewed and authorised the models in question.

- Flexibility in outsourcing activities: The CNMV is planning to take a flexible approach in terms of facilitating the outsourcing of functions or activities which could in turn enable entities to partially relocate certain activities swiftly, as long as doing so complies with the requirements laid down in the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID).

- Initiatives in other areas of importance to petitioning entities such as a commitment not to impose any requirements that go beyond those deriving from European legislation in areas such as recovery and resolution, remuneration policies, market makers, etc. and application of such requirements in full compliance with the principle of proportionality.

The opportunities are also evident at the institutional level with some important multilateral European institutions currently based in London, such as the European Banking Authority itself, considering a move in the wake of Brexit. In this respect, Spain can offer certain advantages relative to other major eurozone countries (particularly vis-a-vis Frankfurt or Paris) in terms of installation, lifestyle and property costs and the provision of infrastructure.

Ten thoughts on how Brexit will impact the financial sector in 2017

From the data and reflections provided in this paper, it seems clear that Brexit will have important ramifications for Spain and for its financial sector in particular. By way of conclusion, here are 10 thoughts on Brexit’s financial impact in Spain:

- The Spanish financial sector’s direct investments in the UK top 16 billion euros, making it an industry of key strategic importance in the context of Brexit, along with others of importance to Spain, such as the tourism and telecommunications sectors.

- The banks’ exposure, measured as the consolidated claims of the Spanish banks resident in Great Britain, is very considerable. As of June 2016, their claims stood at 377.29 billion euros, 18.6 billion euros of which were in the form of claims on banks, 38.51 billion euros on the official sector and 320.19 billion euros on non-financial corporates.

- For 2017, which is when Brexit is expected to be triggered and its implementation to begin, the eurozone banking environment looks far from simple. The Italian banking crisis is an important threat which does not yet appear to be under control.

- Spain’s banks (and other companies) have discovered a source of diversification in the UK which does not have to end with Brexit. Indeed, the Spanish banks’ experience with international diversification constitutes a safeguard in this respect.

- There are, however, aspects related to the potential economic fallout from Brexit which do warrant monitoring. For example, the consequences for the banking business in Great Britain of a slump in business volumes and/or higher unemployment.

- The regulatory environment is one aspect requiring particularly close attention. The Brexit negotiations are going to coincide with finalisation of full implementation of the Basel III capital requirements.

- The Spanish banks operating in the UK will be able to continue to enjoy the advantages afforded by the single European passport and the British regulators are not expected to impose additional impediments or hindrances on their business activities.

- Britain’s departure from the EU does offer opportunities in the financial sector, which the Spanish authorities are already trying to tap. The CNMV, in coordination with the Spanish government, has drawn up a plan for attracting the financial institutions which may be considering moving their headquarters to Spain.

- Spain offers certain advantages in terms of costs and ease of doing business for European regulators or institutions which could move their head offices out of London.

- Given the significance of Spain’s trade and financial ties with the UK, Spain would be advised to be well represented and have a significant voice at the upcoming Brussels-led Brexit negotiations.

Notes

Santiago Carbó Valverde. Bangor Business School and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas