The Great Lockdown of the Spanish economy

In view of the depth of the global crisis, and taking into consideration key domestic imbalances that predate it, Funcas has revised its economic forecasts for Spain. Our baseline scenario now predicts an economic contraction of 8.4%, with adverse effects on unemployment, the deficit, public debt levels, and GDP remaining below pre-crisis levels until 2023.

Abstract: Economic restrictions imposed on March 13th, as well as broader global dynamics, will have a material impact on previously published forecasts. For this reason, Funcas has updated its economic projections. Our baseline scenario now predicts GDP will contract by 8.4% in 2020, with the public deficit and debt levels reaching over 10% and nearly 114% of GDP, respectively. Data indicate that retail, accommodation, food services, cultural and sports activities, and personal services sectors are the most directly affected by lockdown measures. The only sectors expected to end the year with a similar level of GDP prior to the COVID-19 crisis are the primary sector, the mining and energy industries, healthcare and education. As expected, employment levels have also deteriorated, though much less than in earlier crises thanks to short-time work arrangements. Indeed, 3.3 million employees are registered as part of a government sponsored furlough scheme. Although the external sector is expected to make a small positive contribution to GDP, tourism receipts and exports have fallen significantly. Importantly, the Spanish economy’s ability to rebound will largely depend on the maintenance of jobs at sustainable enterprises, the rapid implementation of government programmes, and the Spanish Treasury’s ability to capture financing at reasonable terms.

Introduction

According to the IMF, the COVID-19 crisis poses the biggest challenge for the global economy since the Second World War (IMF, 2020). The dual supply and demand shocks triggered by the pandemic and lockdown measures, coupled with the collapse in international trade, have caused an economic paralysis across continents.

The crisis began its extension in Spain in early March due to a slowdown in demand from the countries hit by the first wave of COVID-19. Alongside the declaration of a state of emergency, the Spanish government introduced restrictions on economic activity and individual mobility, which have further expanded the impact of the crisis.

Funcas conducted preliminary estimates of those impacts in March, assuming a more limited state of emergency than ultimately implemented, as wells as a V-shaped recovery of the global economy, which was in line with the international organisations’ forecasts at the time (Torres and Fernández, 2020). This paper updates this early assessment, layering in more recent predictions for the global economy and key imbalances in the Spanish economy that predate the pandemic.

Performance since the onset of the pandemic

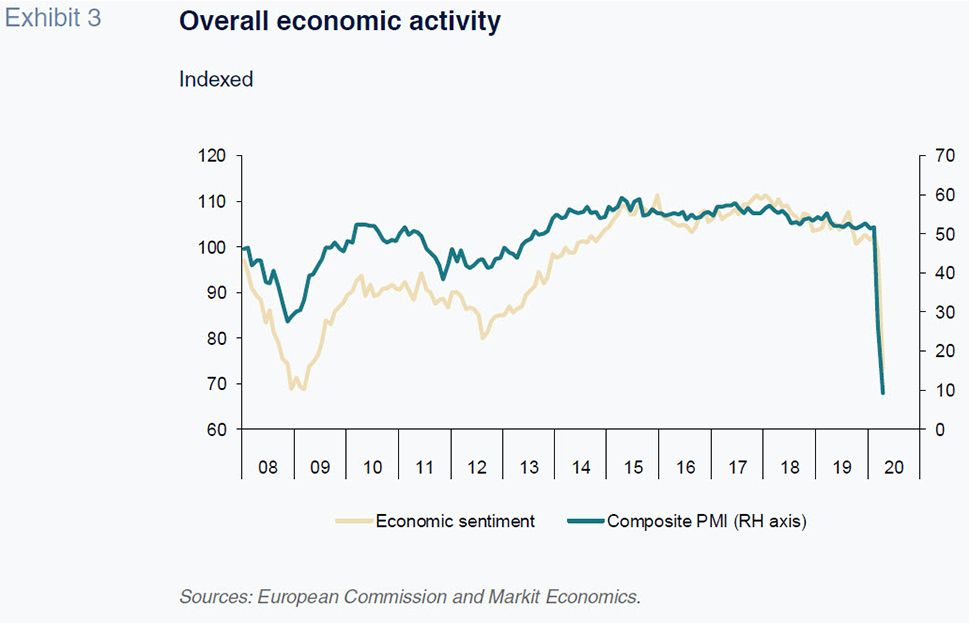

The economic indicators for the first two months of the year pointed to a continuation of the expansion at a similar pace to that observed in the previous quarters, with GDP growth of around 0.4% and job creation even rising in February. By March, however, the indicators exhibited sharp contractions, attributable to economic restrictions imposed on March 13th to contain COVID-19. Data from April, the first full month affected by the lockdown measures, showed an even more pronounced decline. Recall that the sectors most directly affected by the closures –retail, accommodation, food services, cultural and sports activities, and personal services– represent nearly 15% of GDP and have a knock-on effect for the rest of the economy, equivalent to about 6% of GDP.

On the consumption front, retail sales have plummeted abruptly, falling below levels not seen since 2013. In April, car registrations were a fraction of normal levels, even though the consumer confidence index remains above its historic low.

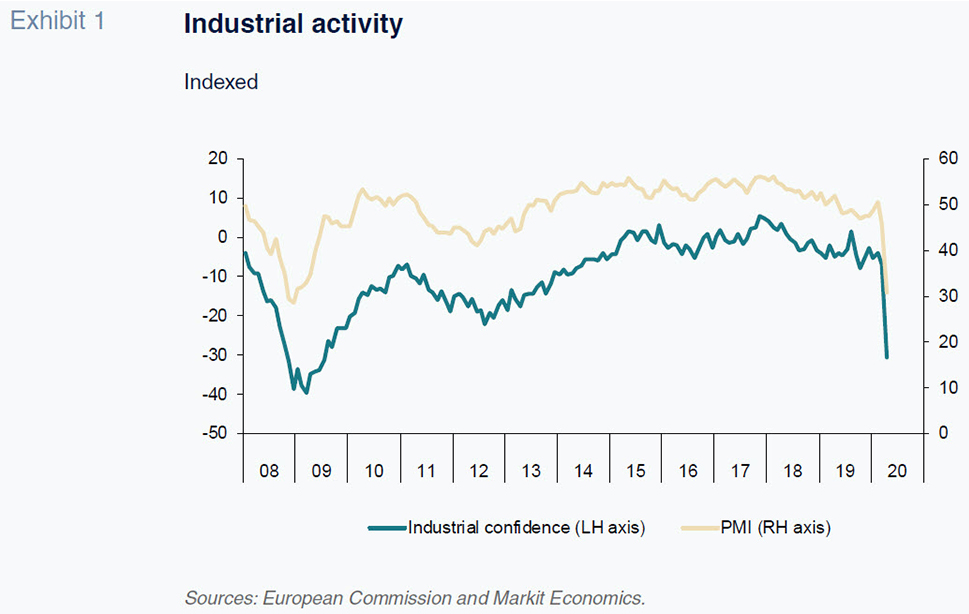

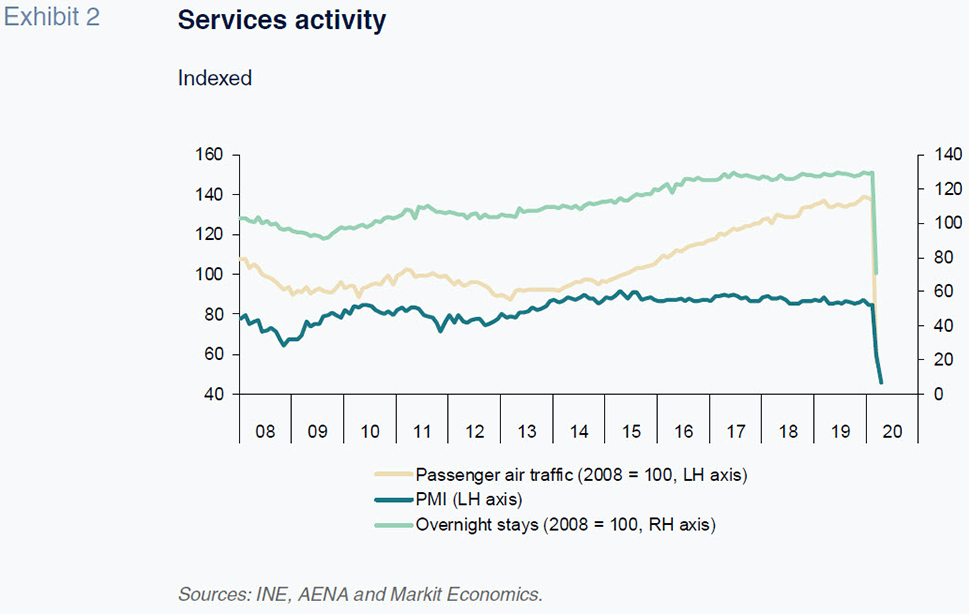

Although the April manufacturing PMI and confidence readings were also above the lows observed during the last recession (Exhibit 1), available data points to a collapse in manufacturing activity. The service sector is even more affected by the pandemic containment measures. The services PMI reading dropped to unprecedented levels in April, with overnight stays and passenger air traffic in March alone falling by 46% and 60%, compared to January-February levels, respectively (Exhibit 2).

The impact on the construction sector has also been sizeable, as revealed by the sharp drop apparent in cement consumption and Social Security contributor numbers in the sector. Note that the construction and real estate activities were already showing clear signs of cooling before the pandemic.

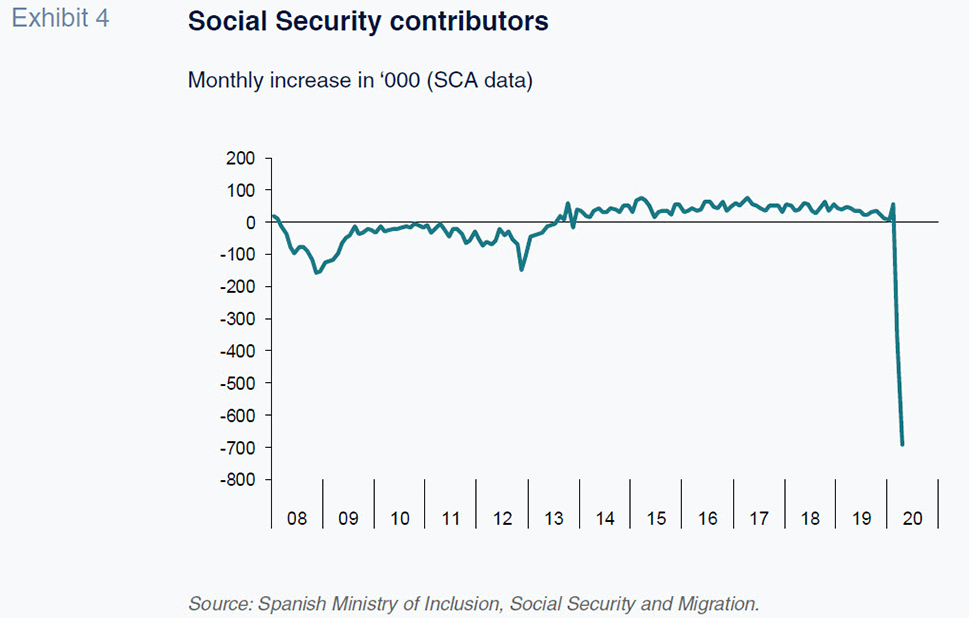

The Social Security contributor numbers provide a more accurate picture of how COVID-19 is affecting employment (Exhibit 4). Contributor numbers fell by almost 900,000 during the second half of March (from when the state of emergency was declared), stabilising somewhat in April, with a net loss of 47,000 contributors over the course of the month. The daily increase in the number of official jobseekers also eased in April compared to the second half of March. At the end of April, the number of employees under the government sponsored furlough scheme (ERTEs for its acronym in Spanish) amounted to 3.3 million. There is no doubt that this scheme has proved most helpful in containing job losses, for now.

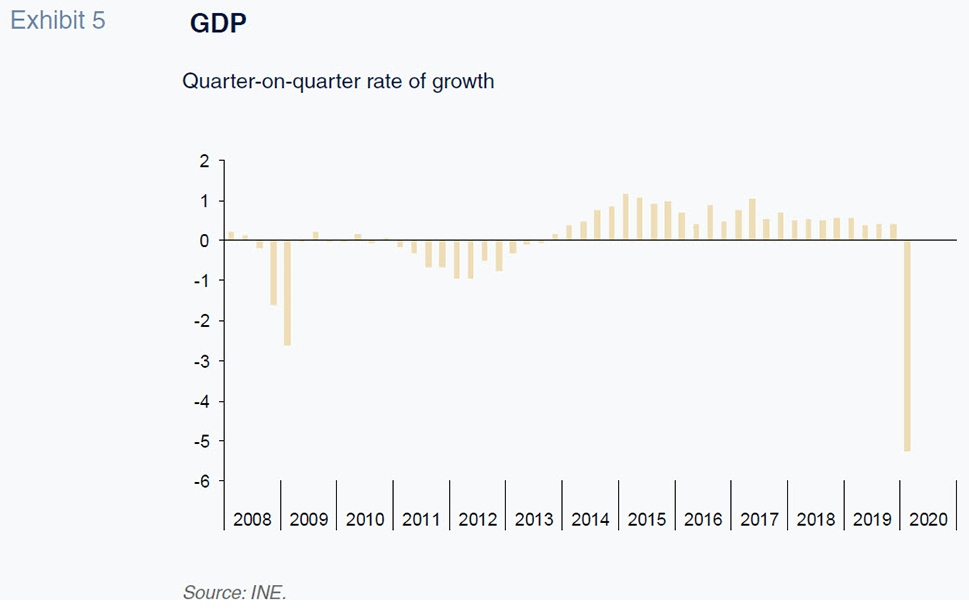

The national accounts for the first quarter of the year, while still provisional and subject to potentially significant revision, evidence the scale of the impact of COVID-19, even though the pandemic only affected the last three weeks of the reporting period. GDP contracted by 5.2% compared to the previous quarter, the biggest drop in the series (Exhibit 5). This was marked by unprecedented declines in all components of demand, with the exception of public expenditure, the only item to register growth. On the supply side, the worst hit sectors were retail, hospitality and transportation, the arts and leisure activities, followed by construction and, lastly, manufacturing. Nevertheless, the full economic impact of the health crisis will not be apparent until the second-quarter figures are released.

The global economy is also reeling from the effects of COVID-19. China’s GDP contracted by 6.8% in the first quarter. Preliminary estimates for the eurozone put the first-quarter decline in GDP at 3.8%. In the US, the contraction was less pronounced –at 1.2%– as widespread transmission and the corresponding shelter-in-place measures came somewhat later than in Europe; however, leading indicators, such as jobless claims have risen to unprecedented levels, foreshadowing an economic impact as severe as other developed economies.

Commodity prices have collapsed and stress has returned to the financial markets. In terms of the latter, a sharp correction in share prices has occurred, volatility is on the rise, risk premiums are spiking and capital is being withdrawn from emerging markets. Nearly every country has imposed lockdown measures, border closures and economic restrictions. Governmental economic policy responses have generally been targeted at propping up the income of affected workers and providing businesses with liquidity, while the central banks have been rolling out liquidity measures in sizeable quantities.

Estimated impact by sector and for the Spanish economy as a whole

Our forecasts are underpinned by these trends and assume that the lockdown will last until mid-May, a few weeks longer than our March estimates. In addition, the easing of the lockdown measures will be slower than initially anticipated, which will have a particularly adverse impact on the sectors more dependent on mobility. The numbers also factor in the emergency measures announced by the Spanish government in March, since expanded to include new initiatives designed to keep businesses afloat until the lockdown is over. Lastly, we assume that the recession will not spill over to the financial sector; specifically, we assume that the ECB’s efforts to contain sovereign risk premiums will be successful (if these assumptions do not hold, the impact would be much worse, as we will outline later).

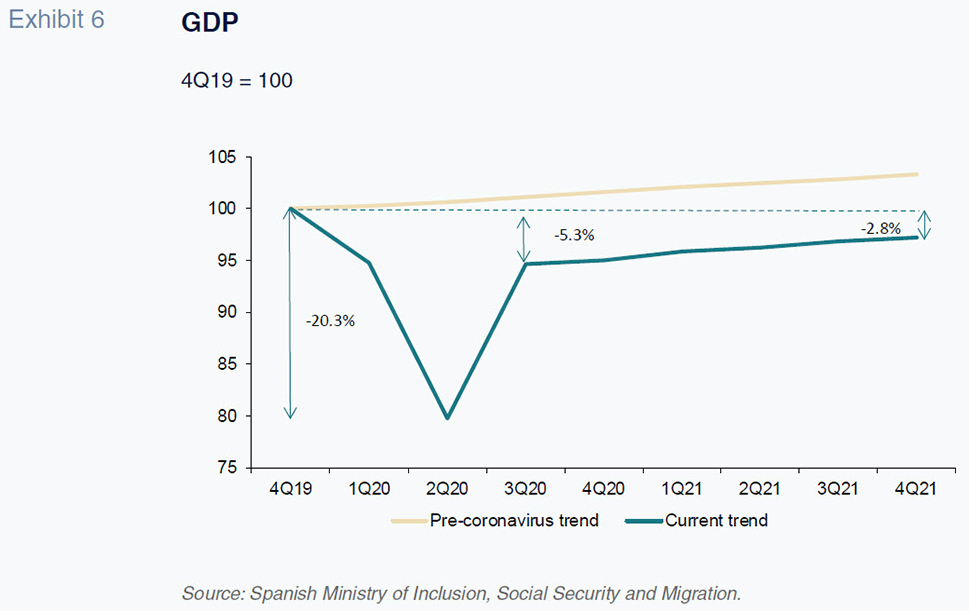

With those assumptions in mind, we estimate that the Spanish economy will sustain an unprecedented contraction during the first half of the year and embark on a recovery from the third quarter, as the lockdown measures are gradually rolled back (Exhibit 6). Despite a rebound in the second half of the year, the economy will contract by 8.4% in 2020 as a whole. The recovery is expected to last for all of 2021, although by the end of that year the economy will not have made up all the ground lost as a result of the Great Lockdown. We forecast that Spain will not return to pre-crisis GDP levels until 2023.

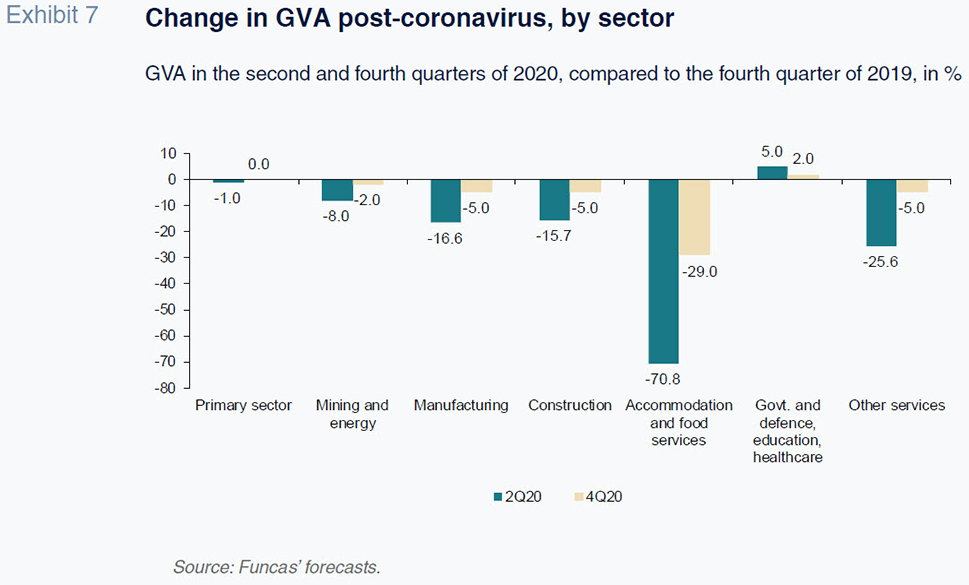

These estimates are based on a simulation of the possible impact of the economic restrictions on each sector of the economy, and their performance once the restrictions are eased. The assumptions regarding the impact of the lockdown on each sector during the state of emergency and, including each sector’s subsequent performance, are necessarily arbitrary; however, they are deemed plausible in light of observations in the Asian economies that were hit by the coronavirus earlier. The results, aggregated into seven major sector categories, are provided in Exhibit 7.

[1]

The only sectors expected to end the year with a similar level of GDP prior to the COVID-19 crisis are the primary sector, the mining and energy industries, healthcare and education. Accommodation and food services will be the hardest hit: GDP in those sectors is expected to be 29% lower year-on-year at the end of 2020.

The shock will also be severe on the demand side. Households will cut back on spending due to the lockdown restrictions, erosion of their disposable income and an increase in precautionary savings, a phenomenon also observed during the 2009 crisis.

[2] We estimate that the household savings rate will rise to 14.3% of gross disposable income, topping the peak reached during the financial crisis.

The impact on investment will be even more significant. This is due to the paralysis of economic activity, a downturn in business expectations, and an environment of tremendous uncertainty. The purchase of capital goods is expected to suffer disproportionately, registering an unparalleled contraction. In total, domestic demand is expected to subtract over seven percentage points from GDP.

Exports, meanwhile, will suffer from the collapse in the global economy. According to the WTO, global trade will contract by 13% this year (a figure that could be multiplied by a factor of almost three depending on the duration of the pandemic and the persistence of trade barriers). Sales of Spanish goods overseas may fare a little better. However, tourism receipts are on course to register an unprecedented plunge, offsetting the less adverse trend in exports in other sectors. Imports are also set to fall, in line with the forecast for internal demand. However, the external sector as a whole is expected to make a small positive contribution to GDP.

The positive contribution by foreign trade will be tangible in the country’s net lending position, which will remain in significant surplus, higher than that recorded in 2019. The drop in the energy bill as a result of the collapse in oil prices will be a contributing factor. The forecasts assume that oil prices (per barrel of Brent) will firm from $30 in March to $45 by the end of the year.

The drop in energy prices, coupled with the recession, is expected to lead to stagnation in consumer prices and a decline in the GDP deflator. The terms of trade will thus improve, one of the few bright spots in this set of projections.

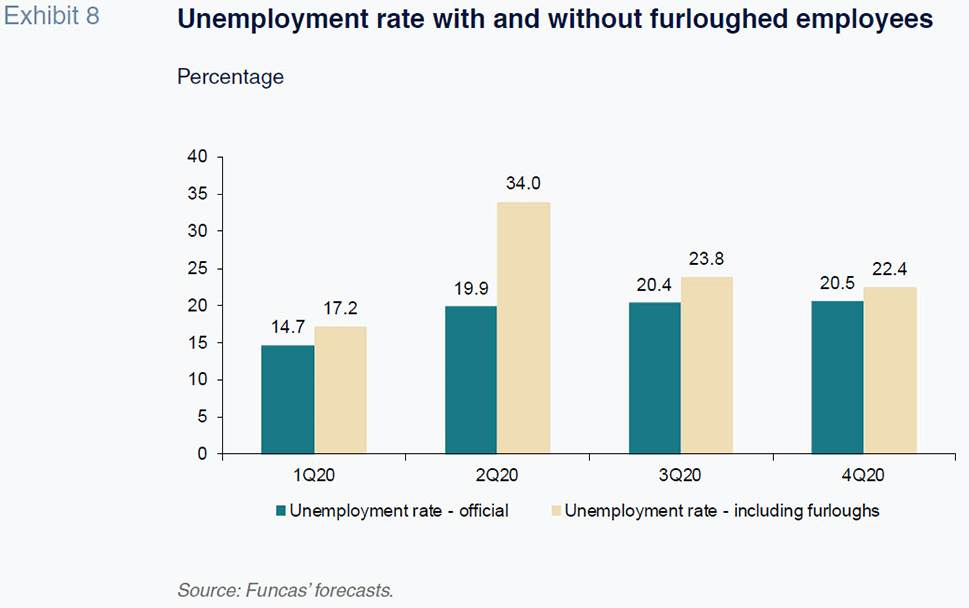

We estimate that job losses will reach 900,000 on average in 2020. If we layer in the jobs affected by the government-sponsored furlough scheme (ERTE), the impact on average annual employment rises to 2.3 million (in terms of full-time equivalents). For the purposes of Spain’s official records (national accounts and the labour force survey), the people affected by the scheme are considered occupied and are not included in the unemployment rate. Unemployment is expected to rise to close to 19% on average in 2020 and fall back to 17% in 2021. If the employees affected by the furlough schemes were recorded as unemployed, the unemployment rate would rise to 24.4% (Exhibit 8).

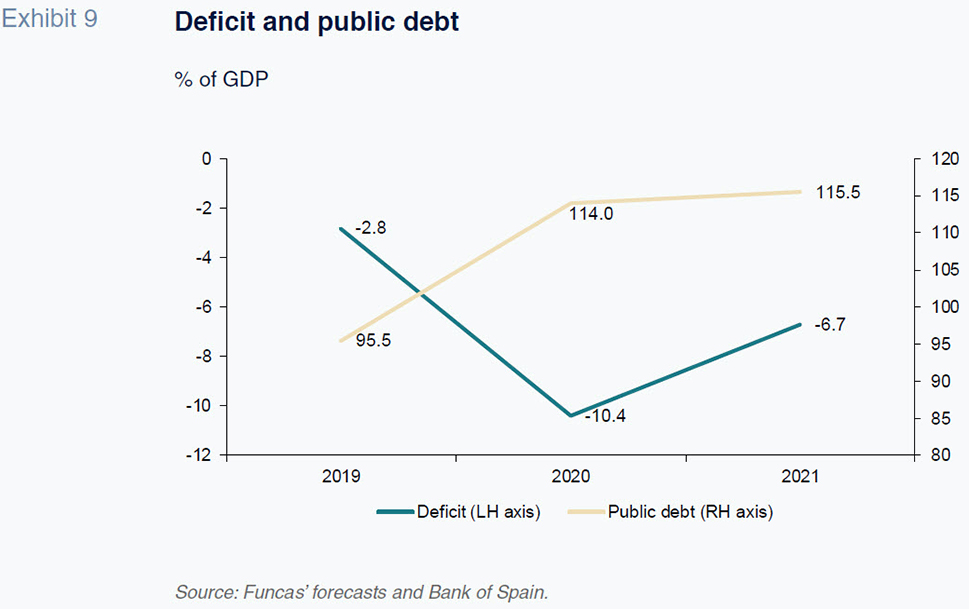

The public deficit is set to widen significantly as a result of the recession and the mitigation measures rolled out in response to the coronavirus. Tax revenue could fall by 58.2 billion euros compared to 2019, while spending is expected to increase by 25.9 billion euros, putting the public deficit at 119.3 billion euros (compared to 32.9 billion euros in 2019), or over 10% of GDP. Driven by the subsequent recovery, the deficit could ease to 6.7% in 2021, which would leave debt at close to 115% of GDP, 20 percentage points above the pre-crisis level (Exhibit 9).

Key role of economic policy

These estimates are framed by an uncommon degree of uncertainty, most notably on account of the fact that we do not know how long the pandemic and its international transmission will last. Furthermore, it is unclear how effective the economic policy response will prove.

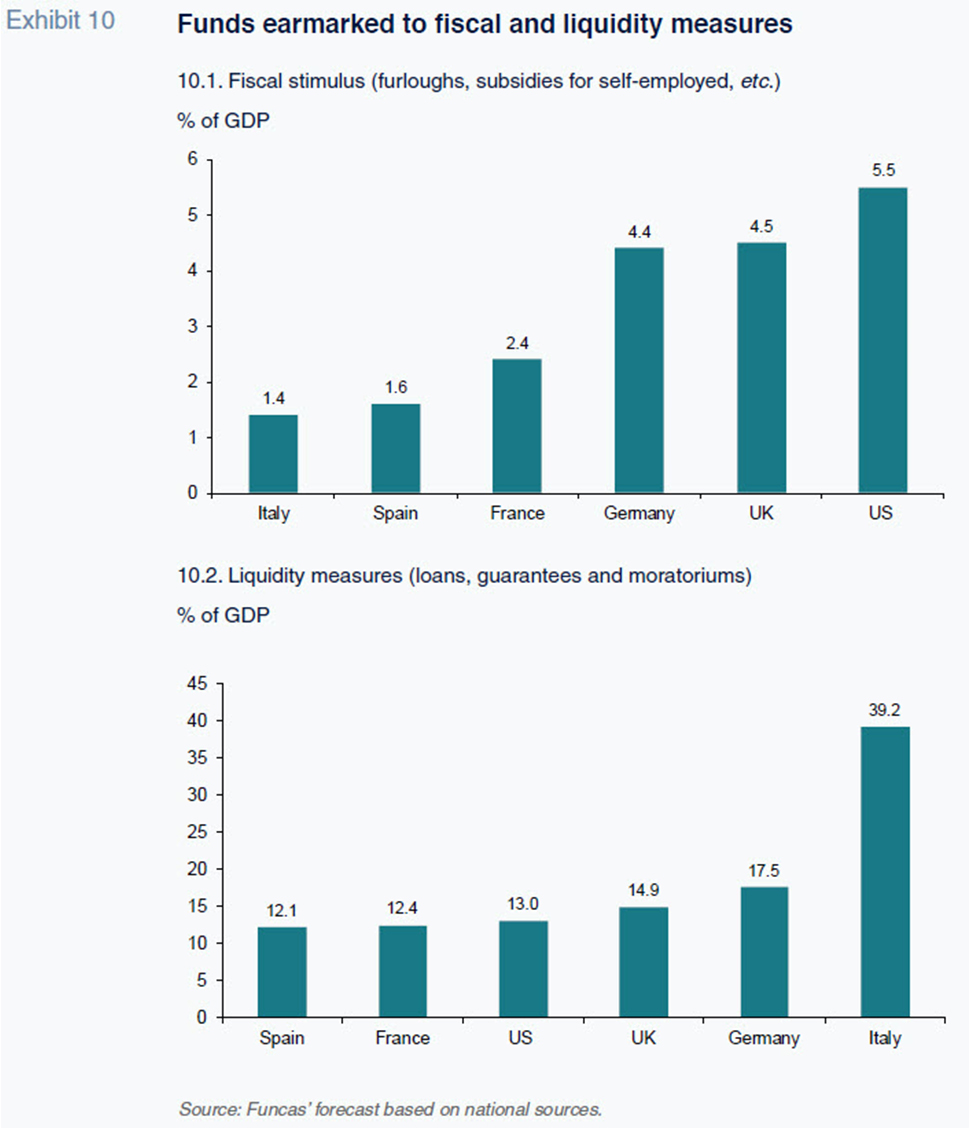

Firstly, the Spanish economy’s ability to rebound will depend largely on the success of the measures aimed at curtailing the closure of businesses. The reduction in the number of businesses registered with the Social Security Administration in March –almost 100,000 (7.4% of total existing firms)– shows that this is one of the biggest risks facing Spain. The creation of a soft credit and government guarantee line totalling 100 billion euros is a step in the right direction, although small by comparison with the measures being rolled out in neighbouring economies (Exhibit 10). The loan guarantees and moratoriums, while substantial, similarly fall in the bottom half of the ranking. Moreover, the aid being extended to SMEs and the self-employed consists primarily of guarantees and soft loans, whereas other countries are also providing direct subsidies or grants. Denmark, notably, is compensating its SMEs in proportion to the income lost as a result of COVID-19.

Elsewhere, the financial crisis has taught us that the maintenance of jobs at sustainable enterprises can play an essential role as an automatic stabiliser. Against that backdrop, the sharp increase in the number of employees covered by the furlough schemes is a positive development in cushioning the impact of the crisis on employment. However, the Spanish job market is characterised by a high percentage of employees on short-term contracts who do not usually benefit from these schemes. In other countries, like Germany, the employment measures specifically cover these vulnerable groups, reducing the risk of long-term unemployment.

Lastly, policy effectiveness depends on the institutional capacity to implement the programmes in a rapid and well-targeted manner. The emergence of bottlenecks in the management of the measures, such as the loan guarantees and employment policies, could impede the flow of funds and trigger a slew of bankruptcies. Public servant job mobility, a common practice in the UK and South Korea, for example, can help alleviate such situations. In Spain, we are seeing the temporary redeployment of public servants in some sectors, such as healthcare, but not in others.

Importantly, the intensity of the recovery will also depend on the terms on which the Spanish Treasury can capture financing. According to its pre-crisis schedule, the Treasury was planning to issue around 10 billion euros a month in 2020 (to refinance and fund the public deficit, which was moderate at the time). However, issuance volumes need to be scaled up considerably to cover the deficit generated by the crisis and the private debt which the state will indirectly inherit as a result of its assumption of private sector liabilities.

For now, that financing has been locked-in thanks to several exceptional bond issues, covering the Treasury’s needs for the next few months. Moreover, the ECB has expanded its government bond repurchase activity, via its special pandemic programme (PEPP), while easing country issuer limits. Thus, although the country risk premium has widened by close to 150 basis points, it remains at a manageable level.

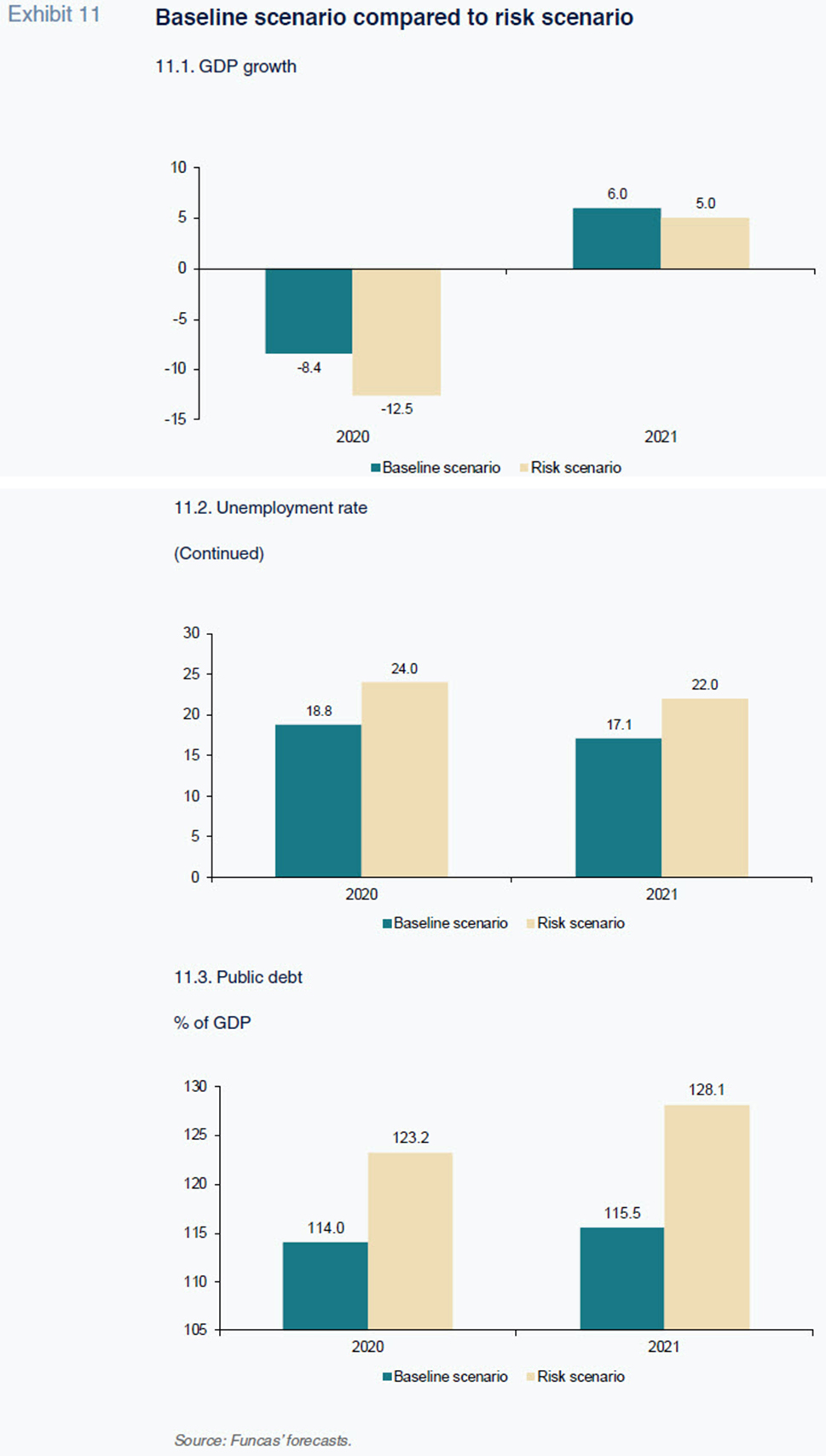

However, if policy is not successful in propping up the real economy and the risk premium were to soar, the scenario would shift significantly. An increase in the risk premium of over 400 basis points (to put it close to the level reached in 2011) coupled with a sharp increase in bankruptcies would drive an economic contraction of 12.5% and push unemployment to 24%, 4.1 and 5.2 percentage points higher than our baseline scenario for 2020, respectively. In 2021, the gap would widen even further (Exhibit 11). That scenario of heightened uncertainty would also imply a considerable risk of financial sector contagion.

In short, current circumstances mean Spanish economic policy faces a dual challenge. Firstly, it needs to take decisive action, underpinned by well-designed policies, to position the economy for a rebound as the lockdown is rolled back. Secondly, it needs to secure financing on reasonable terms in order to limit the risk of financial crisis. Unfortunately, the first initiative puts strong upward pressure on the public deficit, complicating the second task, which is financing the deficit, while keeping the risk premium under control. A tension which will have to be managed carefully over the coming months.

Notes

For the purpose of these estimates, the various sectors’ activity is measured in terms of gross value added (GVA), which is a very close proxy for GDP.

As for household consumption, we conducted a similar simulation exercise to project the trend in expenditure on each of the categories included in the Household Budget Survey, using the contraction sustained in each expenditure category during the 2009 recession as our reference for the likely trend after the lockdown.

References

IMF (2020).

World Economic Outlook. April.

TORRES, R. and FERNÁNDEZ, M. J. (2020). Spanish economic policy in response to Covid-19.

SEFO. March.

WTO. (2020).

Methodology for the WTO trade forescast of April 8 2020. Economic Research and Statistics Division. Retrievable from:

https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/methodpr855_e.pdf

Raymond Torres and María Jesús

Fernández. Economic Perspectives and

International Economy Division, Funcas