The major central banks and the fight against climate change: Assessing the latest policy initiatives

While it is widely acknowledged that climate policy-making is the prime responsibility of governments, central banks are also taking steps to address climate change within their remits. That said, the extent to which central banks integrate climate risks into their work varies depending on each institution’s respective mandate and domestic political preferences vis-à-vis climate change.

Abstract: While it is widely acknowledged that climate policy-making is the prime responsibility of governments, central banks are also taking steps to address climate change within their remits. An examination of the integration of climate change considerations into the operations of the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England (BoE), and the Federal Reserve (Fed) highlights that both the ECB and the BoE are more proactive than the Fed in their commitments and policy measures to tackle climate risks. Notably, the BoE has pioneered several initiatives, while the ECB has recently made more significant advancements in other areas related to supervision and collateral rules. The extent to which central banks integrate climate risks into their work varies depending on each institution’s respective mandate and domestic political preferences vis-à-vis climate change.

Introduction

Climate change is considered one of the most acute challenges for our society, and the response of central banks has not been to stay on the sidelines. While it is widely acknowledged that climate policy-making is the prime responsibility of governments, central banks are today taking steps to address climate-related financial risks (climate risks) within their remits, which typically include the responsibility for price stability, financial stability and the safety and soundness of financial institutions.

Central banks and supervisors have only recently started to consider climate change relevant to their mandates, but their involvement has gained momentum over the last years due to a growing recognition of the substantial risks that climate change poses to financial stability and the global economy. Their work in this area has been underpinned by international collaboration via different fora (G20, FSB, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision), with the Network of Greening the Financial System (NGFS) playing an instrumental role.

But are all central banks equally involved in the fight against climate change or do they follow different approaches? To answer this question, we explore how three of the largest central banks, the ECB, the BoE and the Fed, are integrating climate change into microprudential supervision, financial stability and monetary policy. Central banks have also engaged with different degrees of ambition in efforts to reduce their carbon footprint or to green their non-monetary policy portfolios. However, these aspects will not be covered in the article, as they are considered less relevant from a policy perspective.

Both the ECB and the BoE seem to go further than the Fed in their commitments and policy measures to tackle climate risks, with the BoE having been a first mover in many areas and the ECB having gone further in others. Yet, the Fed’s actions with regards to climate change have a more limited scope, mainly focusing on microprudential supervision and financial stability and not addressing monetary policy.

Does this situation solely reflect the decision of central banks, or could other elements help explain it? As we will argue, some of the climate related measures undertaken by central banks go further than their primary mandates and focus on supporting general economic policies. This, coupled with the challenging political situation in the United States and the apparent decrease in ambition in UK government’s climate policies, could explain why it is difficult for the Fed to take forward far-reaching measures when it comes to climate change, and why the BoE’s leadership in the matter seems to be losing momentum.

Microprudential supervision and financial stability

The work of central banks and supervisors on climate change began with its recognition as a source of financial risk, through both physical risks (such as extreme weather events) and transition risks (arising from the transition to a low-carbon economy). It was therefore understood that it is within each other their remits to ensure that the financial system remains resilient to these risks.

Early recognition and initial steps

Out of the three institutions under consideration, the BoE has been the first mover, starting to consider climate-related financial risks as early as 2015. In September that year, Mark Carney, the Bank’s governor, delivered his famous speech [1] in which he alerted of the risks of climate change for the financial system and the possibility of a climate-driven systemic financial crisis. After a first report in 2015 focused on the insurance sector, in September 2018, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) published a review of risks from climate change facing the UK banking sector [2] and set out a program of future work on climate risks. And in the 2019 Financial Stability Report, [3] the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) undertook a top-down assessment of UK banks’ exposures to physical and transition risks. In addition, the BoE’s leadership is also visible in its role as one of the founding members of the NGFS in 2017, as well as its early adoption of a climate strategy and internal governance framework to deal with climate issues.

The ECB joined the NGFS

[4] as a permanent member in May 2018, the year in which its climate work accelerated. Climate risks were identified

[5] in the ECB Banking Supervision risk assessment for 2019. A special feature in its

November 2019 Financial Stability Review [6] also assessed the impact of physical and transition risks.

The Fed still lags behind its peers in the integration of climate risks into its supervisory and financial stability roles, but its work seems gradually approaching the mainstream of G20 central banks. The Fed started in 2019 to publicly acknowledge the systemic nature of climate risks, a shift possibly influenced by discussions in international forums in which the institution participated. The Fed took an important step by formally joining the NGFS in December 2020, soon after the new Biden Administration took office. [7] In early 2021, the Fed created [8] two internal committee groups to enhance its understanding on climate risks: the Supervision Climate Committee (SCC), with a focus on supervised firms, and the Financial Stability Climate Committee (FSCC). The institution has repeatedly described its mandate regarding climate risks as important, but narrow’ and ‘tightly linked to its responsibilities for bank supervision and financial stability.

Supervisory expectations

In line with its pioneering role, in April 2019, the BoE became the first central bank to set out climate supervisory expectations. [9] They covered four key areas (governance, risk management, scenario analysis and disclosure) and called banks and insurers to effectively identify, measure, manage and report on their exposures to climate risks. Since then, climate risks have been among the supervisory priorities of the PRA, which has provided further thematic feedback via two Dear CEO letters, incorporating observations from its supervisory processes. In its July 2020 letter, [10] the PRA highlighted some identified gaps in the entities’ practices and set year-end 2021 as a deadline for firms to have fully embedded its expectations. From 2022, the PRA shifted from assessing implementation to actively supervising firms against climate expectations. In its October 2022 letter, [11] the PRA assessed that further progress in the implementation was still needed by all firms and warned that the wider supervisory toolkit could be used for those whose efforts are judged insufficient. This suggests that additional capital charges within the Pillar 2 capital framework might be eventually imposed.

In the euro area, the ECB-Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) published in November 2020 its guide on climate-related and environment risks,

[12] setting out its supervisory expectations on risks management and disclosure. In 2022, the Bank launched a thematic review which involved assessing the institutions’ climate risks strategies, governance and risk management frameworks and processes. Results of the exercise

[13] were published in November 2022, together with a code of good practices

[14] that institutions could use to align their practices with the ECB’s expectations. The ECB also set staggered deadlines

[15] for banks to progressively meet all the supervisory expectations, with full alignment envisioned by the end of 2024. At present, findings on climate risks have already fed into the supervisory process and for a relatively small number of banks this has led to an impact on Pillar 2 capital requirements. Furthermore, in the last few years, climate risks have been among the supervisory priorities of the SSM, escalating to its second priority for the period 2024-2026.

[16]

In October 2023 the Fed issued, jointly with the two other key US federal banking regulators, interagency principles for climate-related financial risk management for large financial institutions, [17] consolidating draft guidance separately proposed in 2021 and 2022. The principles provide high level supervisory expectations regarding how climate risks should be managed by banking organizations with over $100 billion in consolidated assets. The Fed explicitly clarifies that the principles neither prohibit nor discourage financial institutions from providing any type of legal banking services. In contrast with the supervisory expectations of the other institutions, banks are also expected to ensure that vulnerable communities and underserved customers are not inadvertently harmed by their climate-risk mitigation efforts. It is interesting to note the two dissenting votes in the Fed’s adoption, reflecting the lack of consensus in the country over climate risks.

Climate stress tests

The BoE was the first central bank to outline plans to conduct a climate stress testing exercise. In July 2019, the Bank announced [18] that its 2021 Biennial Exploratory Scenario –an exercise the Bank conducts regularly to assess risks not covered by annual solvency stress tests– would explore the resilience of the UK financial system to climate physical and transition risks. The exercise was launched [19] in June 2021 and tested both large banks and insurance companies against three 30-year scenarios involving early, late and no additional policy action. The exercise was conceived as a learning tool to develop the capabilities of both the BoE and participants and was not intended to be used to set capital requirements related to climate risks. The results, published in May 2022, [20] revealed a material level of losses for firms in all scenarios, which caused a significant drag on their annual profitability. Projected losses would be substantially lower in an early and orderly scenario (30% lower compared to the late action scenario). Those findings have fed into the supervisory dialogue with firms.

In July 2022, the ECB made public its results of the bottom-up climate stress test. The exercise

[21] revealed that under a short-term, three-year disorderly transition risk scenario and the two physical risk scenarios (flood risk and drought and heat risk), the combined credit and market risk losses for the 41 banks providing projections would amount to around EUR 70 billion. As in the case of the BoE’s exercise, losses were projected to be notably lower under an orderly climate transition.

The ECB also conducted a top-down economy-wide climate stress test [22] in September 2021 showing that the effects of climate risks are concentrated in certain geographical areas and sectors, with potential significant impact for corporates and banks most exposed to climate risks. Moreover, the impact on banks in terms of losses would mostly be driven by physical risk and would potentially be severe over the next 30 years.

In September 2022, the Fed announced a pilot climate scenario analysis exercise [23] for the six largest US banks to analyse the impact of different scenarios for both climate physical and transition risks on specific assets in their portfolios. The exercise aimed to learn about large banks’ climate risk-management practices and to enhance the ability of the Fed and participating banks to identify, measure, monitor, and manage these risks. It was made clear [24] that climate scenario assessments were considered distinct and separate from regulatory stress tests, due to their exploratory nature and the absence of capital consequences. The exercise was launched in early 2023 and aggregate insights from the exercise were expected by the end of 2023. At the time of writing, the results had not been published.

Capital requirements

The BoE has explored the link between climate change and the regulatory capital framework. Its 2021 climate change adaptation report [25] declared that regulatory capital was not an appropriate tool to address the underlying causes of climate change and cautioned against the introduction of “green supporting” or “carbon penalizing” factors. However, it acknowledged that current regulatory capital frameworks only partially captured climate risks. To delve into the topic, the BoE convened a Research Conference in October 2022 and presented its conclusions [26] in March 2023. No policy change was announced, but the Bank committed to exploring further the possible gaps in the capital framework and whether specific regulatory tools might be appropriate, in particular macropudential approaches.

In the EU, while the ECB is not directly involved, the European Banking Authority (EBA) has recommended targeted enhancements to accelerate the integration of environmental and social risks into Pillar 1, though it still remains to be seen whether this will be translated into effective regulatory changes. In addition, the ECB and the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB)

[27] are exploring the possible use of some existing macroprudential tools to address climate risks, such as the systemic risk buffer.

Monetary policy

Central banks around the world are increasingly integrating climate change considerations into their monetary policy roles, although the integration is obviously framed by each central bank mandate. As we will see, there are significant divergences on each side of the Atlantic.

Mandates

In the case of both the BoE and the ECB, their monetary policy role seeks to maintain price stability as a primary objective, and subject to that, as a secondary objective, to support general economic policies of the UK government and the EU, respectively.

Both central banks consider climate change could have crucial implications for their primary objective of price stability mainly through four channels that they need to monitor and understand: (1) impairment of monetary policy transmission mechanisms, (2) a possible decrease in the equilibrium real rate of interest, (3) direct impact on inflation dynamics; and, (4) protection of the central bank balance sheet. For this reason, they are stepping up their research efforts to understand how climate change and the transition to net zero will affect the macroeconomy and integrate these aspects into their macroeconomic models.

Regarding their secondary objective, both the UK and the European Union have ambitious climate policies and a determined commitment to climate neutrality.

In this sense, and focusing on the BoE, the remits of its three policy committees were updated in March 2021 in the annual remit letter sent by the Chancellor of the Exchequer outlining the government’s priorities and objectives for the Bank. The new remits included the transition to an environmentally sustainable and resilient net-zero economy as part of the government’s economic strategy that the committees must take into consideration as the secondary objective. In any case, the Bank’s interpretation of the new remit has been rather conservative. It has described [28] its role in the net-zero transition as to understand how different transition pathways could affect the macroeconomy, the stability of the wider financial system, and the safety and soundness of the firms it regulates.

The approval of the ECB’s strategy review of 2020-21 was a game-changer to accelerate its involvement in climate matters. Subsequently, in July 2021, the ECB presented an action plan

[29] to include climate change considerations for monetary policy implementation. As stated by Christine Lagarde in her speech in November 2023 before the European Parliament, the ECB views climate change relevant for its work from the perspective of both its primary and secondary objective. Still, at the same time, several members of the Executive Committee of the ECB have made it clear that the ECB is a climate policy-taker, rather than a climate policy-maker.

The Fed understands that its ‘dual mandate’ of price stability and maximum employment leaves no margin for integrating climate change into its monetary policy role. The Fed’s Chair Jerome Powell has spoken out unambiguously on several occasions alerting that the Fed should stick to its statutory goals and authorities and that without explicit congressional legislation, it would be inappropriate [for the Fed] to use [its] monetary policy or supervisory tools to promote a greener economy or to achieve other climate-based goals. As he put it in early 2023, the Fed is not and will not be a “climate policymaker”. [30]

Climate risk disclosure and management in monetary policy portfolios

The BoE was the first central bank to disclose the climate risks associated with its monetary policy portfolio, which it started to do as part of its annual climate financial disclosure report since June 2020. Its 2023 disclosure report assesses climate-related risks associated with its different asset portfolios using different metrics associated with climate physical and transition risks and via scenario analysis.

The ECB has also conducted in 2022 a climate risk stress test [31] of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet, which revealed that both transition and physical risks have a material impact on its risk profile. The Eurosystem published climate-related information on its corporate bond holdings for the first time in March 2023, [32] with future reports to be published annually.

Greening monetary policy operations

In response to its new remit, the BoE announced in May 2021 its intention [33] to adjust the composition of its Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme (CBPS) to take account of the climate impact of issuers. The greening approach [34] was adopted in November 2021 and aimed at reducing by 25% the carbon intensity of this portfolio by 2025 and achieving full-alignment with net-zero by 2050. To that end, corporate purchases will be tilted towards those firms complying with certain climate-eligibility criteria related with being the strongest climate performers within their sectors based on a climate scorecard. This involved abandoning the market neutrality principle that had traditionally guided purchases to minimise distortions on relative borrowing cost across sectors.

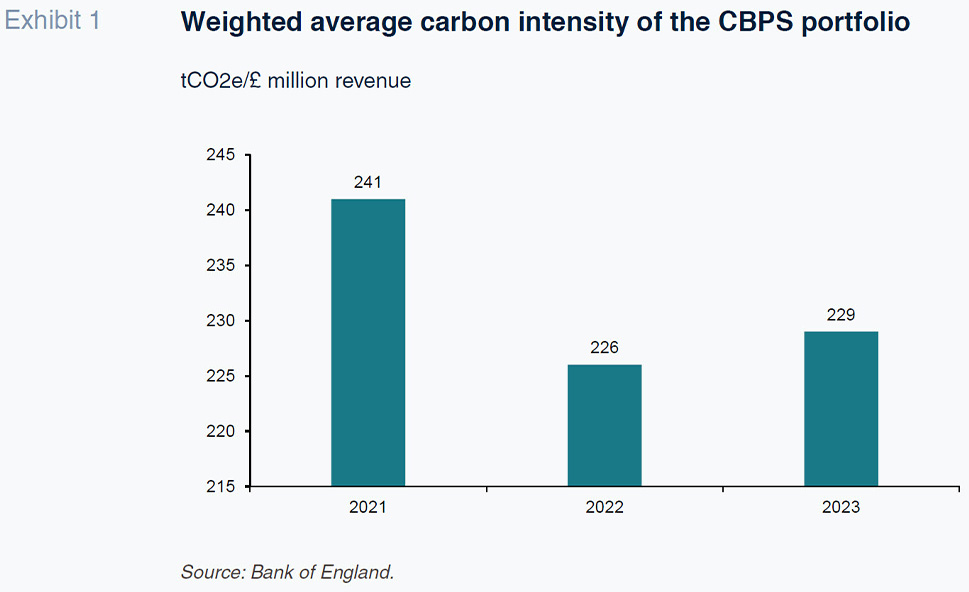

To date, the greening of the CBPS has been the BoE’s flagship policy instrument for supporting the transition, as the Bank has not yet followed a similar direction with its collateral framework. However, the practical relevance of this instrument has been rather limited. At the time the greening started, the Bank was only reinvesting the proceeds of maturing bonds, and only a few months later those reinvestments were halted, and an active bond sales programme was launched. However, the BoE could restart corporate bond purchases if a new crisis strikes. Indeed, as shown in Exhibit 1, the Weighted Average Carbon Intensity (WACI) of the CBPS has only slightly decreased between 2021 and February 2023, driven by a combination of changes in portfolio weights and changes in companies’ carbon intensity.

In the case of the ECB, the Bank started in October 2022 to tilt its corporate purchases towards issuers with a better climate performance. The shift covered both the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) and the Pandemic Emergency Programme (PEPP) and required the calculation of a specific climate score for each issuer. Since the Governing Council of the ECB

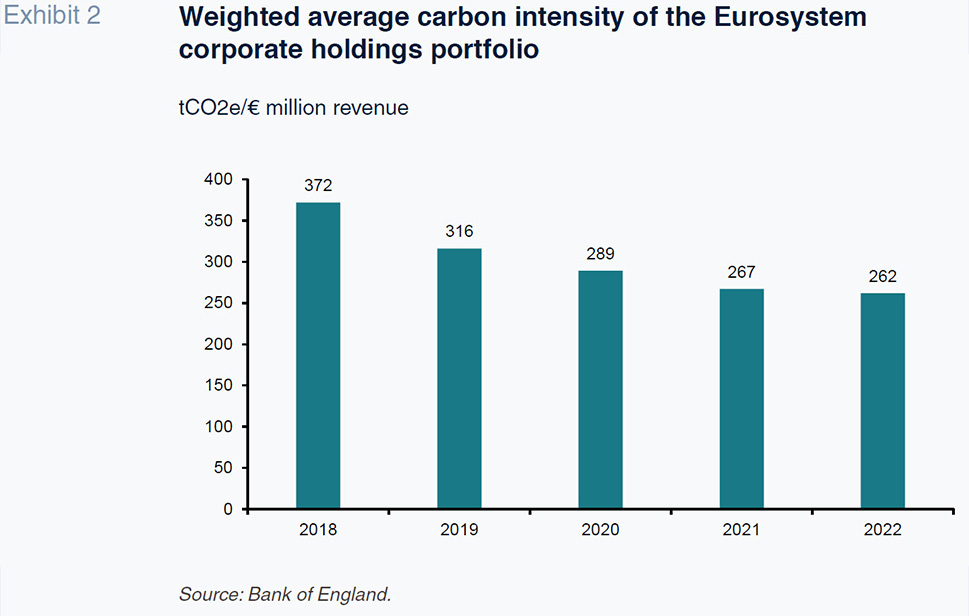

[35] decided to discontinue reinvestments under the APP as of July 2023, the shift of the ECB towards green investments has significantly decreased. As per Exhibit 2, the WACI for the ECB’s corporate sector portfolios significantly declined, but 75% of the decrease happened between 2018 and 2020, mainly due to issuers’ decarbonisation efforts. After 2021, a rebound in issuers’ emissions occurred due to increased economic activity and demand for energy and materials post-COVID. The ECB began its tilting practices in the last quarter of 2022, leading to a lower WACI for reinvestments in the final months of 2022 compared to the previous nine months. In any case, similar to the BoE, the overall impact of the tilting practices has been relatively limited due to their short duration.

The ECB has also taken steps to green its collateral framework. Since 2022, climate risks are considered when reviewing haircuts applied to corporate bonds used as collateral, and before the end of 2024, the institution will limit the share of assets issued by entities with high carbon footprint that can be pledged as collateral by counterparties when borrowing from the Eurosystem. In addition, as of 2026, the ECB will require issuers to comply with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) to accept their collateral.

The ECB is also exploring other measures. ECB Executive Board member Frank Elderson (2023) [36] has advocated the expansion of the corporate bond greening strategy to public sector bond holdings, which represent the bulk of monetary policy assets. He also has suggested the greening of the targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), although this has been discarded for the time being, [37] as data challenges make it difficult to define the green target criteria.

Looking at the other side of the Atlantic, the Fed does not plan the greening of its monetary portfolio for the reasons indicated previously. When discussing this in 2020, [38] the Fed’s Chairman, Jerome Powell, expressed his commitment to market neutrality, stating that the Fed historically shied away strongly from taking a role in credit allocation and that he would be reluctant to see the institution picking one area as creditworthy and another not.

Conclusions

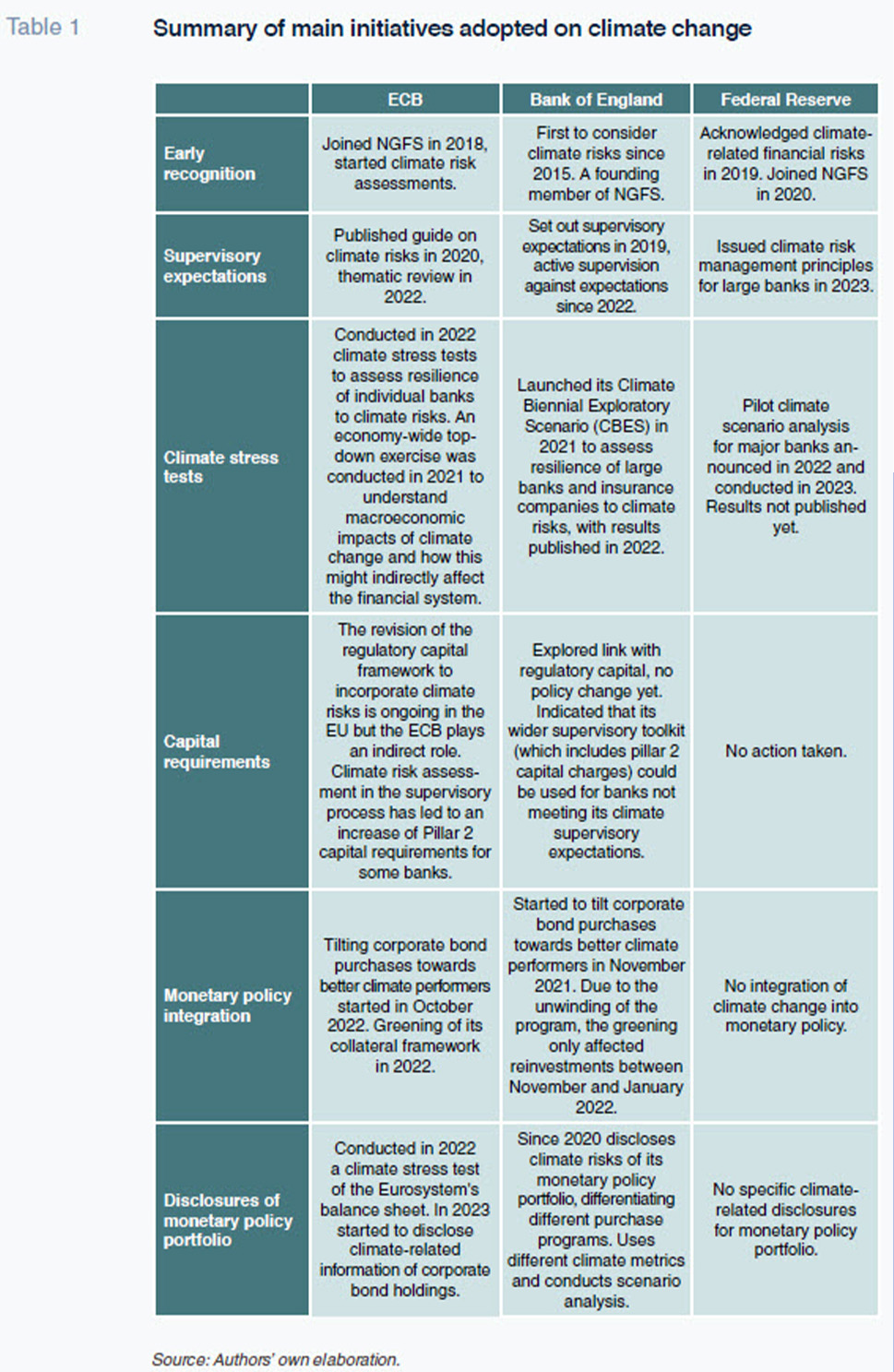

While central banks normally show high degrees of convergence in terms of objectives, frameworks and tools, the extent to which they have integrated climate risks into their work varies depending on the domestic political context. A summary of the main actions undertaken by each central bank can be found in Table 1. As shown in the table, monetary policy is the area where there is the most divergence, despite their shared view that the transition to a low carbon economy must be led by governments.

The Bank of England has been a pioneer in most of the areas, but its leadership role on climate matters seems now to be losing momentum. For example, the Bank has not launched any significant new measure in the last year and climate change appears to be less present in the Bank’s public speeches. In addition, the Bank has been rather conservative in the interpretation of this secondary objective and seems to assume its role in the transition is to ensure financial and monetary stability. Besides, recent events might suggest the UK government has relegated climate policies to a lower level of priority, such as the new more proportionate and pragmatic approach to net zero announced in September 2023. In the same line, the annual remit letter to the FPC [39] that Chancelor Hunt released in November 2023 has also been interpreted [40] as a downgrade of climate work in the government’s guidance. Recent criticism over the BoE’s performance in taming inflation has also spread to the Bank’s climate work. In November 2023, the House of Lords [41] recommended that the Treasury should “prune” the BoE’s remit, considering that its expansion to climate change and other issues could jeopardise its independence and hinder its ability to prioritise its primary objective of price stability.

The ECB started climate related work later than its UK peer, but it has today the most ambitious and pro-active approach to climate change of the three institutions. This is visible not only on the supervisory front, where climate risks are already having an impact on Pillar 2 capital requirements for some banks, but also in the ambitious greening of its collateral rules, a move the BoE has not taken yet. The ECB’s action on climate matters has certainly increased in parallel with the pressure of the European Parliament and the growing ambition of the EU’s climate policies, especially after the launch of the European Green Deal. This is also reflected in public statements by the ECB’s leadership.

The Fed has a differentiated approach compared with the other two institutions as regards monetary policy. This is not so much the case as regards financial stability and supervision, where the institution is slowly approaching the central banking mainstream, though still with a more cautious stance. Indeed, supervisory expectations have only been addressed at the largest institutions, climate stress testing is in a pilot phase and its public statements are full of caution. As for monetary policy, while the Fed could be more active due to the potential impact of climate change on price stability and employment, it has clearly refrained from any pro-active measure to integrate climate risks or to support the transition. Such a divergence from its peers is explained not only by the absence of a similar secondary objective in its mandate, but also due to a strong and long-dated political and social polarisation in the US over climate change, which also has an impact on climate policies and, more recently, on the ESG movement. This domestic political landscape is a big constraint for the Fed, even if at present the US administration (and in particular the US Treasury) is strongly supportive of climate action.

Notes

Emma Navarro and Judith Arnal. Trade Experts and State Economists