Income, savings and household wealth in Spain: 21st century transformation

Spanish households and their finances have undergone major structural transformation since the start of the century. These changes should be taken into consideration to ensure proper public policy design.

Abstract: Spanish households and their finances have undergone major transformation since the start of the century, from the time of Spain’s inclusion in the eurozone. Taking a dual macro and micro perspective, an analysis of Spanish households over time, as well as relative to those of other large eurozone economies, reveals various major structural changes as regards the composition of the universe of Spanish households, and the main trends with respect to their income, savings, and wealth over the period. Indeed, driven in part by immigration, the number of Spanish households has increased in absolute terms as well as relative to the rest of Europe, meanwhile their average size has contracted, albeit remaining larger than the eurozone average. In parallel, there has been a widening of the wealth gap with respect to Europe, accompanied by a widening of the generational wealth gap in Spain, with households with the oldest heads having seen their income increase. In contrast, an area where there has been little change is households’ scant propensity to save, remaining low and highly volatile compared to the levels in other eurozone economies. Nevertheless, this has not prevented Spanish households from accumulating wealth on equivalent or higher levels relative to neighbouring countries, a trend plausibly explained by Spanish households’ propensity to invest in the real estate market, and which is once again adding cost pressures for younger households. These changes should be taken into consideration to ensure proper public policy design.

Introduction

Households constitute a basic economic unit. Given their macroeconomic implications and impact on financial stability, the behaviour of households conditions and determines numerous public policies aimed to tackle their vulnerabilities. Moreover, far from being stable units, their composition and characteristics change over time and therefore impact their basic economic and financial decisions about spending, saving and investment. Naturally, the economic environment itself, which shapes household income levels and expectations, also informs those decisions.

A recent study published by the Afi Emilio Ontiveros Foundation (Berges and Manzano, 2023) focuses on the changes affecting Spanish households over the past quarter of a century. To do so, it relies on two sources of information that, adequately combined, yield extraordinarily relevant information. Firstly, the Spanish economy’s annual financial and non-financial accounts for 2000-2022 provide a macro vision. Secondly, to get a micro vision, we rely on the results of The Survey of Household Finances (EFF in its Spanish initials) that have been carried out in Spain during this first quarter of a century. The use of these two sources of information has the added advantage of enabling a comparison with other major eurozone economies (Germany, France and Italy) over the same timeframe for which there is comparable information: on the one hand, the national accounts, which are standard under the scope of Eurostat; and, on the other, the Household Finance and Consumption Surveys (HFCS) that have been harmonised within the eurozone’s central banking system since 2010 (in which the Spanish equivalent has been integrated since then).

Economic research into the financial conduct of households is primarily articulated around the life-cycle hypothesis of consumption whereby savings are the difference between income in each period and the optimal level of expenditure individuals can afford currently in light of their budget restrictions. On that basis, household saving behaviour depends on the utility function (which determines whether they decide to spend today or in the future), uncertainty around future income, and the accessibility and efficiency of the financial markets to which households can turn to place their savings or borrow money. Under the life-cycle hypothesis formulated by Nobel prize-winner Franco Modigliani mid-last century, the accumulation of savings and purchase of durable goods takes place during an individual’s working years, with dissaving generally taking place during the last years of retirement, during which income falls and individuals start to monetise some of the wealth accumulated in order to maintain certain levels of consumption and services. Certain variants and elements have since been layered into the life-cycle model to explain household behaviour more accurately, providing an analytical framework for interpreting the latter that is widely accepted.

Structural changes

As already indicated, there are structural elements, such as household size and composition, that condition household finances. Before progressing with our analysis of the key changes that have unfolded since the turn of the century, it is important to note that these basic units have transformed significantly. There has been extraordinary growth in the household population (4 million more households to total close to 19 million); they have shrunk considerably in size, extending the trend observed in previous decades (2.5 members on average today); and they have aged notably.

In addition to a combination of demographic factors (drop in birth rate and increase in life expectancy), the household population in Spain has been marked by unprecedented net immigration inflows, with immigrants accounting for over 70% of the growth of seven million people in the Spanish population during the period under analysis (the highest among comparable economies in relative terms). The Spanish population has increased by 17% during the period, well above the growth seen in France (12%) and very significantly above that observed in Italy (4%) and Germany (a mere 1%).

In parallel to the growth in the number of households, higher than the growth observed in the population for a variety of reasons (and not just demographic), average household size has fallen, albeit still larger than the eurozone average and, above all, than the average size in France and Germany. Households comprising just one or two members currently account for 55% of the total, which is 10 percentage points more than at the turn of the century.

Moreover, the share of younger households –those whose household head is under the age of 35– plummeted by nearly eight percentage points during that same period. And not only because the young population has decreased but also because the conditions facilitating the creation of new households have deteriorated sharply. So much so that after the above-mentioned shrinkage, the percentage of ‘young’ households in Spain is currently less than the equivalent shares in France and Germany (barely over 7% compared to 16%-18%, respectively).

Income gap

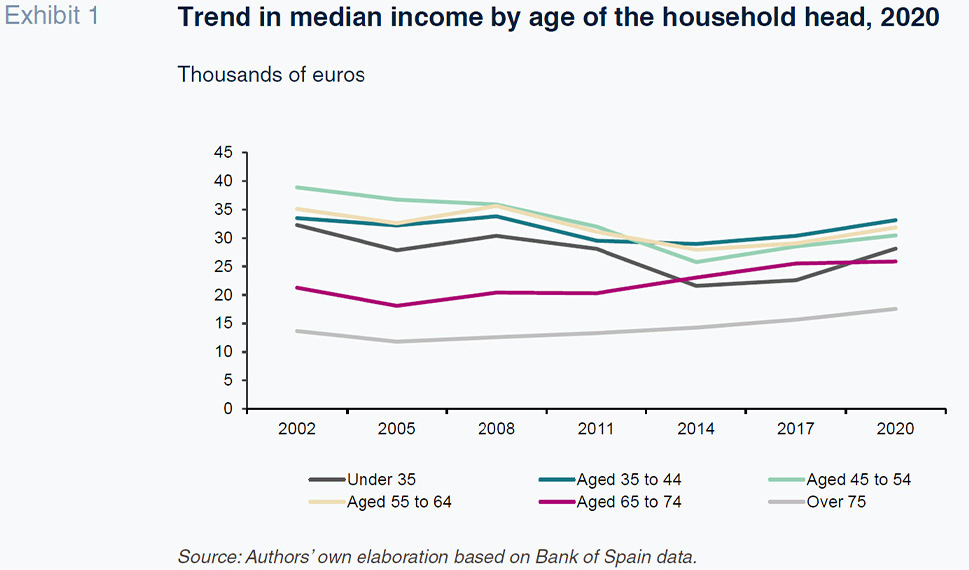

Disruption in the convergence of the Spanish economy with its European counterparties in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath, following a spell of unsustainable growth predicated on a real estate boom underpinned by ultra-low interest rates after Spain joined the euro, is another key explanatory factor for the changes seen in household finances in Spain. As a result of that crisis, despite the subsequent recovery, gross disposable income per capita has barely revisited the level observed at the turn of the century in real times, widening the gap relative to the eurozone average and the levels presented by some of the region’s largest economies. In addition to, and no less significant than, the increase in the income gap relative to Europe, an analysis of income levels by age bracket reveals a widening of the generational wealth gap within Spanish households, in addition to verifying the life-cycle theory. The households with oldest heads (over the age of 65) have seen their income increase, without sustaining contractions in the wake of the crisis of 2008, in contrast to what has happened in all other age brackets, most notably in those with household heads under the age of 35, which have not been able to recover the income levels enjoyed at the start of the century in real terms. The pension income protection policies are largely responsible for this pattern.

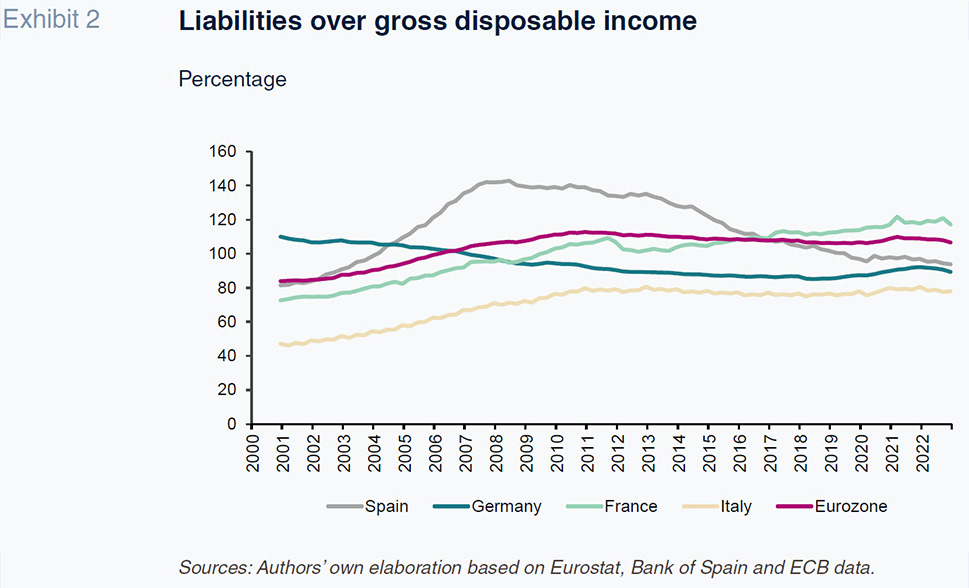

Coinciding with the real estate boom that preceded the 2008 crisis, Spanish household leverage shot up, before going on to converge towards average European levels. Indeed, household leverage has dipped below that average in recent years. The ratio of financial liabilities to household gross disposable income has decreased from a peak of 140% to 90%, compared to the eurozone average of 107%.

Savings rates and wealth accumulation

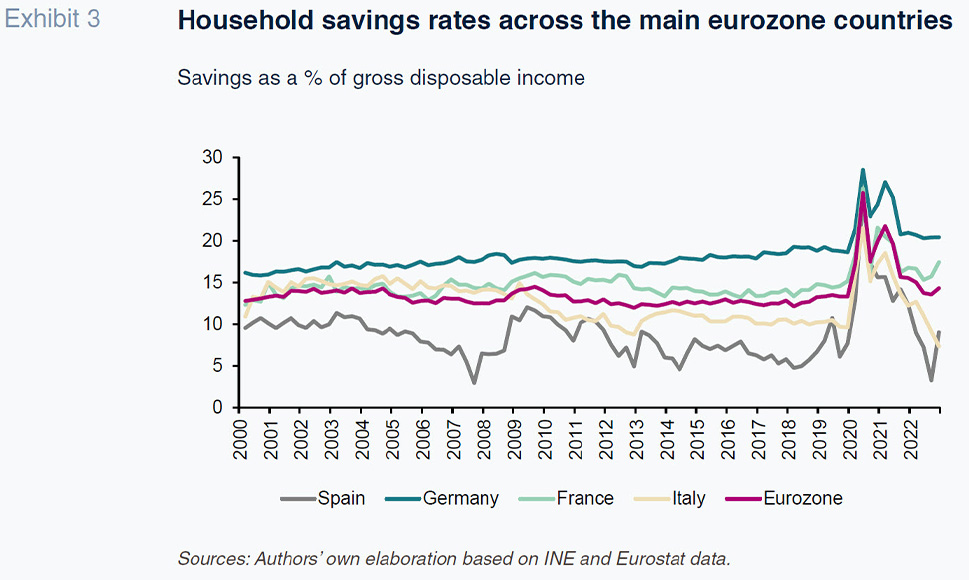

An area where there has been very little change is households’ scant propensity to save. Likewise, Spanish household savings levels remain highly volatile compared to the levels observed in other eurozone economies. Spain’s low yet volatile savings rates are undoubtedly influenced by historic and cultural factors on aggregate such as greater appreciation for enjoying the present moment and greater trust in social safety nets and the welfare state, especially a more generous public pension system in comparative terms. Other factors at play, however, include relatively lower income levels and the greater sensitivity of Spanish GDP and employment to cyclical swings.

One of the most eye-catching outcomes of the analysis performed is the fact that the relatively lower savings rate in historic terms has not prevented Spanish households from accumulating relatively high levels of wealth, equivalent to or even higher than those seen in neighbouring economies. This counter-intuitive result is attributable to the fact that the process of household wealth accumulation is not only the result of the net purchase of assets as a consequence of the materialisation of savings over time. The amount of wealth accumulated (and its composition) is impacted by changes in the value of the assets that compose it, which stem from different variations in the factors that determine its valuation (interest rates, share prices, real estate prices, etc.). Indeed, asset revaluation can be, as or more decisive in the accumulation of wealth than the actual purchase of assets as a result of the gradual investment of savings. That is certainly the case in Spain, where that effect is responsible for nearly three-quarters of the growth in household wealth during the period under analysis, compared to 54% in France, the next best case, and a much lower 23% and 30% in Germany and Italy, respectively. The fact that more savings have gone into property in Spain and that real estate assets are the asset class to have revalued the most (despite the swings related with the boom and bust either side of 2008), fuelled by the structural reduction in long-term rates since Spain joined the eurozone, adds plausibility to this explanation.

Although there are other factors, it would also go a long way towards explaining the greater concentration of wealth that has taken place, as illustrated by the higher percentiles of the wealth distribution: the richest 1% of households garnered 13.8% of total household wealth in 2002, compared to 22% by 2020, according to the Household Finance Survey. And the share of the richest 10% of households has increased from 43.9% to 53.9%.

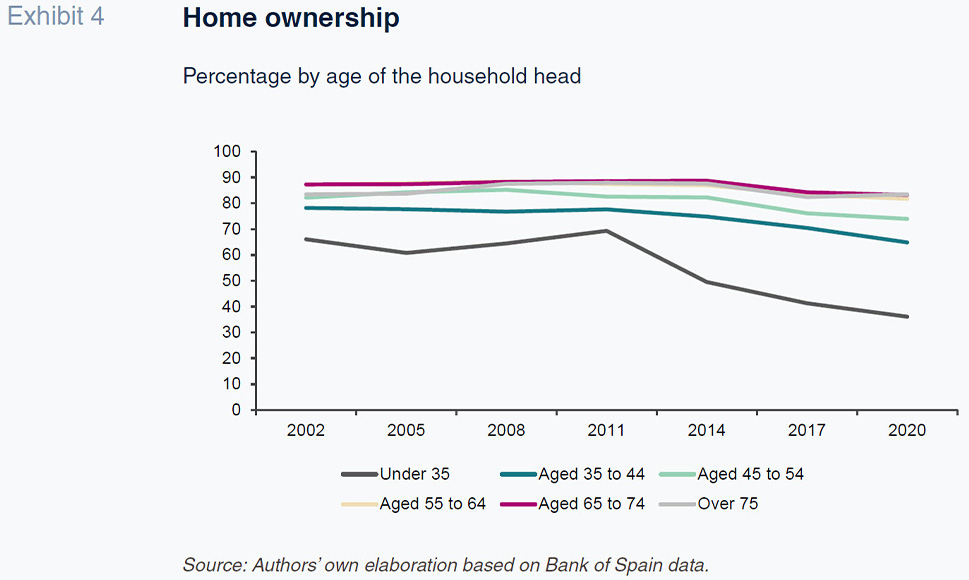

Asset revaluation, coupled with the above-mentioned erosion of real income, has made it harder for new generations to buy homes. Although this is not the only reason, as living arrangement preferences are also shifting, the fact is that younger households have halved their home ownership (35%, down from 70% at the turn of the century. This shift towards a new “way of living” based on rental is running up again the absence of a deep enough rental market capable of cushioning sharp upward pressure on prices. Here again we see the difficulties facing young adults looking to leave home and create new households in Spain.

Despite a doubling in the percentage of households living in rented housing (from 10% to 20%), Spanish households continue to present a stronger preference for home ownership than those of other eurozone economies. This leads to a greater concentration of financial wealth among high-income households, to the extent that today, after non-stop growth in that concentration, the highest-income 10% of households encompass virtually 50% of household financial wealth, as strictly defined. That concentration is even more pronounced in retirement savings, which are so important in other eurozone economies but are barely a factor outside of the most privileged income brackets in Spain.

References

BANK OF SPAIN. (2007). Survey of household finances (EFF) 2005: methods, results and changes between 2002 and 2005.

Economic Bulletin, 12/2007. Bank of Spain.

BANK OF SPAIN. (2022). Survey of Household Finances (EFF) 2020: methods, results and changes since 2017.

Economic Bulletin, 3/2022. Bank of Spain.

BERGES, A. and MANZANO, D. (2023).

Finanzas de los hogares 2000-22: escaso ahorro y ampliación de la brecha generacional [Household finances 2000-2022: Scant savings and wider generational gap]. With input from Marina Asensio and Marina García. Afi Emilio Ontiveros Foundation.

EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK. (2023a).

Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS). https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/ecb_surveys/hfcs/html/index.en.htmlEUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK. (2023b). Household Finance and Consumption Survey: Results from the 2021 wave.

ECB Statistics Paper, No. 46.

Marina Asensio, Marina García and Daniel Manzano. Afi