Europe’s new regime for macroeconomic policy coordination: A first look

In the last days of its rotating presidency, the Spanish government successfully led negotiations in the Council of the European Union to agreement on a new regime for macroeconomic policy coordination. Once agreed by the European Parliament, the new framework will significantly increase national ownership of fiscal consolidation, while at the same time easing the path of adjustment in comparison with the framework it replaces.

Abstract: The Spanish Presidency of the Council of the European Union (EU) announced the Council’s agreement on a new framework for macroeconomic policy coordination on 21 December 2023. The agreement marks the culmination of a pan-European debate over macroeconomic policy and fiscal adjustment that started during the pandemic, as governments took stock of the role of macroeconomic policy coordination in shielding Europe’s economies from the full impact of restrictive measures imposed to fight the spread of COVID-19. The new framework places emphasis on the need for national ownership over efforts at fiscal consolidation. It also builds on the recognition that the fiscal positions of member state governments are different from one country to the next. At the same time, it acknowledges that all EU member states should have incentives to invest in areas of common interest, including responding to climate change, fostering the digital and green transitions, and bolstering national defence. It also takes steps to simplify the design and the monitoring of fiscal consolidation measures to make them more credible and more transparent, which should bolster efforts to curtail macroeconomic imbalances and reduce unwanted volatility in financial markets.

Background

This agreement marks the culmination of a three-year debate over macroeconomic policy coordination and fiscal consolidation that started during the pandemic. The European Commission triggered the general escape clause under the existing macroeconomic governance framework –called the Stability and Growth Pact– in March 2020 to give member state governments greater flexibility in responding to the impact of restrictive measures needed to contain the spread of COVID-19. As those responses to the pandemic pushed up public deficits and debts, national governments across Europe began to worry about whether they would be able to meet the requirements for fiscal consolidation under the existing rules once the general escape clause was deactivated (Jones, 2021).

Member state governments also worried that excessive efforts at fiscal consolidation would slow down any recovery from the pandemic and might even tip Europe’s economy into a recession. The fact that any fiscal consolidation would necessarily coincide with a tightening of monetary policy and a shrinking of the combined balance sheet of the European System of Central Banks heightened the risks for macroeconomic performance (Jones, 2022).

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine added further complications by pushing up inflation on the back of rising food and energy prices that required national governments to spend additional funds to reduce the impact of higher prices on domestic households and industries. The faster pace of inflation did help reduce outstanding levels of public debt by raising the value of gross domestic product, but higher expenditures associated with short-term price-supports and longer-term efforts to enhance energy security and to accelerate the green transition pushed in the opposite direction. For some member states, a major fiscal consolidation effort could not be avoided (Jones, 2023).

The Spanish and Dutch governments published a joint paper in April 2022 insisting that the time had come for the European Union to adopt a more flexible and credible framework for macroeconomic policy coordination.

[1] Their partnership drew attention because the two governments traditionally –and self-admittedly– took different sides of the fiscal consolidation debate.

[2] That joint paper served as inspiration for a European Commission proposal made in April 2023 (European Commission, 2023). When the Spanish government took up the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union in July, it knew that it would need to finish any negotiations by December. The Council had already decided to deactivate the general escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact at the end of the year.

The negotiations were complicated because of domestic political considerations in several major countries – including Spain and the Netherlands (Tama, 2023). They also had to consider significant technical critiques of the European Commission’s proposal (see, e.g., Darvas, Welslau and Zettelmeyer, 2023). More fundamentally, the Spanish Presidency needed to address divisions among the member states about the trade-off between having common rules for all countries with clear European oversight and allowing a differentiated approach with greater national ownership. The agreement reached on 21 December strikes a delicate balance. The next step is to win the support of the European Parliament.

Overview

The agreement consists of three documents, the most important of which is a proposal for a new “preventative arm” for the Stability and Growth Pact – meaning a procedure to help member states avoid running unsustainable fiscal policies. Establishing such a procedure would require a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council. This is the document that representatives of the Council must negotiate with the European Parliament and so it takes the form of a “negotiating mandate” (Council of the EU, 2023a). The other two documents relate to an amendment to the “corrective arm” of the Stability and Growth Pact, the “excessive deficits procedure” for dealing with member states whose fiscal position is already considered to be unsustainable (Council of the EU, 2023b), and an amendment to the requirements for the budgetary frameworks of the member states (Council of the EU, 2023c). These documents have been agreed in the Council and only need to be brought to the European Parliament for consultation. Nevertheless, the three documents repeat many of the same instruments, safeguards, and specific terminology, which means any change in the first document through negotiations with the European Parliament could have implications for the language in the other two.

The new “preventative arm” contains the most innovative elements in the agreement. Many of these innovations are found in details that are more meaningful to experts in macroeconomic policy coordination than to a wider audience. The decision to limit activation of the general escape clause to one year, renewable, is one example. When they activated the general escape clause during the pandemic, they realized they did not have clear guidelines for when or how it should be deactivated (Jones, 2020). The same problem applied to the activation of country-specific escape clauses. The new framework shifts the burden onto any decision to extend the activation. Like many of the details in the new framework, that shift is important, but only for a limited audience. Nevertheless, four changes stand out as relevant for anyone interested in understanding the evolution of European fiscal policy.

First, the focus for policy coordination will rest on “net expenditure” which the proposed legislation defines as “government expenditure net of interest expenditure, discretionary revenue measures, expenditure programmes of the Union fully matched by revenue from Union funds, cyclical elements of unemployment benefit expenditure, and one-offs and other temporary measures” (Council of the EU, 2023a: 18). Public debts and deficits are still useful as indicators of how well or how poorly a government is doing in managing its finances in broad terms and some safeguards trigger depending on the level or change in these variables, but “net expenditure” is the main indicator to watch in assessing the performance of government efforts at fiscal consolidation.

Second, any planning for fiscal consolidation will be “risk based and differentiated”. The notion of risk-based planning refers to the central role given to the European Commission in doing a debt-sustainability analysis when generating a recommendation about the trajectory that member state governments should follow in the evolution of their “net expenditure” when their debts are higher than 60 percent of GDP or their deficits are higher than 3 percent of GDP. The differentiation reflects the fact that national governments can make their own plans on how to achieve that trajectory. The point to underscore is that any adjustments to public spending must be structural. Temporary or on-off measures like wind-fall taxes or asset sales do not change net expenditure under the definition. Those plans are supposed to extend over four or five years depending upon the usual life of the parliament and member states can ask to revise the plan when governments change after elections – subject to evaluation by the Commission.

Third, governments may extend the planning horizon to seven years if they commit to reforms or investments that –in the language of the proposal– will improve growth potential, support fiscal sustainability, address common EU priorities, incorporate relevant country-specific recommendations, and result

in a higher level of public investment over the planning period than they showed over a similar period immediately prior. This extension lowers the average annual fiscal adjustment and so creates incentives for governments to avoid cutting public investment as part of their consolidation efforts and to double-down on efforts to promote common objectives. When those new investments are made, governments are even allowed to build the impact of those investments on fiscal consolidation or economic growth into their future plans.

Fourth, the proposal includes numerous requirements to enhance the transparency of the whole process by strengthening the European Fiscal Board, highlighting national planning assumptions, and openly debating the methodology used by the European Commission in its debt sustainability analysis, which has to be adopted by the Council. Once that methodology is agreed, the Commission will have to make its debt sustainability analysis publicly available together with the data and coding for replication. This emphasis on transparency should not only strengthen the credibility of any fiscal consolidation plans but also reduce unnecessary volatility in financial markets. The more financial market participants are able to understand, replicate, and agree on assessments of debt sustainability, the less likely they are to speculate against those national governments engaged in fiscal adjustments.

These elements feature in the amendments to the excessive deficits procedure and to the requirements for national budgetary frameworks in predictable ways – to focus attention on “net expenditure”, to incorporate the Commission’s debt sustainability analysis, to allow for greater national differentiation, to encourage productive public investments, and to enhance the transparency of the whole process. The three documents also connect this new framework to more structural efforts to ensure the sustainability of government finances through the Treaty on Stability, Coordination, and Governance in and Economic and Monetary Union that was signed in 2012– also known as the “fiscal compact” – and to broader concerns about addressing macroeconomic imbalances. In that sense, the agreement is not just about fiscal policy but also about the direction of macroeconomic policy coordination more generally.

Assessment

If it is formally adopted, the new framework should make the fiscal consolidation process more effective in two respects. Governments with initially high debt-to-GDP ratios will have lower fiscal adjustment requirements under the new rules than they would under the existing framework. The current rules require governments to reduce excessive public debts on an annual basis by 5 percent (or 1/20th) of the difference between their actual debt-to-GDP ratio and the reference value of 60 percent. For the governments in Greece and Italy, which have debt-to GDP ratios more than double the reference value, this represents a huge effort. Few if any governments have made such large fiscal adjustments over the kind of sustained period that the rules require. By contrast, the new framework requires less adjustment on an annualized basis to meet the kind of net expenditure requirements to fit the existing debt sustainability analysis done by the Commission and the annualized effort is even lower when the planning horizon extends seven years (Darvas, Welslau and Zettelmeyer, 2023; Zettelmeyer, 2023). This lower level of effort is still significant, but it is also more realistic. And when paired with national ownership of the fiscal adjustment process, it is more likely to survive the domestic political opposition that is usually generated by austerity measures.

When a government’s debt-to-GDP level is close to the reference value, the adjustment required under the new rules is greater than under the current regime. The effort required to meet a proportional rule like the one that currently exists diminishes as you approach the target; the effort required under a net expenditure rule like the one agreed in the Council does not. Instead, governments should progress in a linear fashion until the consolidation is sufficient to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio below the 60 percent reference value and to contain the deficit-to-GDP ratio close to 1.5 percent – which is low enough to allow for governments to use fiscal policy in response to economic downturns without crossing above the 3 percent reference value. In this way, the new framework encourages member states to continue consolidation measures until they arrive at a point where they are unlikely to confront problems with debt sustainability even during periods of poor macroeconomic performance. Moreover, the new framework gives governments the opportunity to consult with the Commission about setting a sustainable trajectory for net expenditure when their debts and deficits are already below the reference values of 60 percent and 3 percent, respectively.

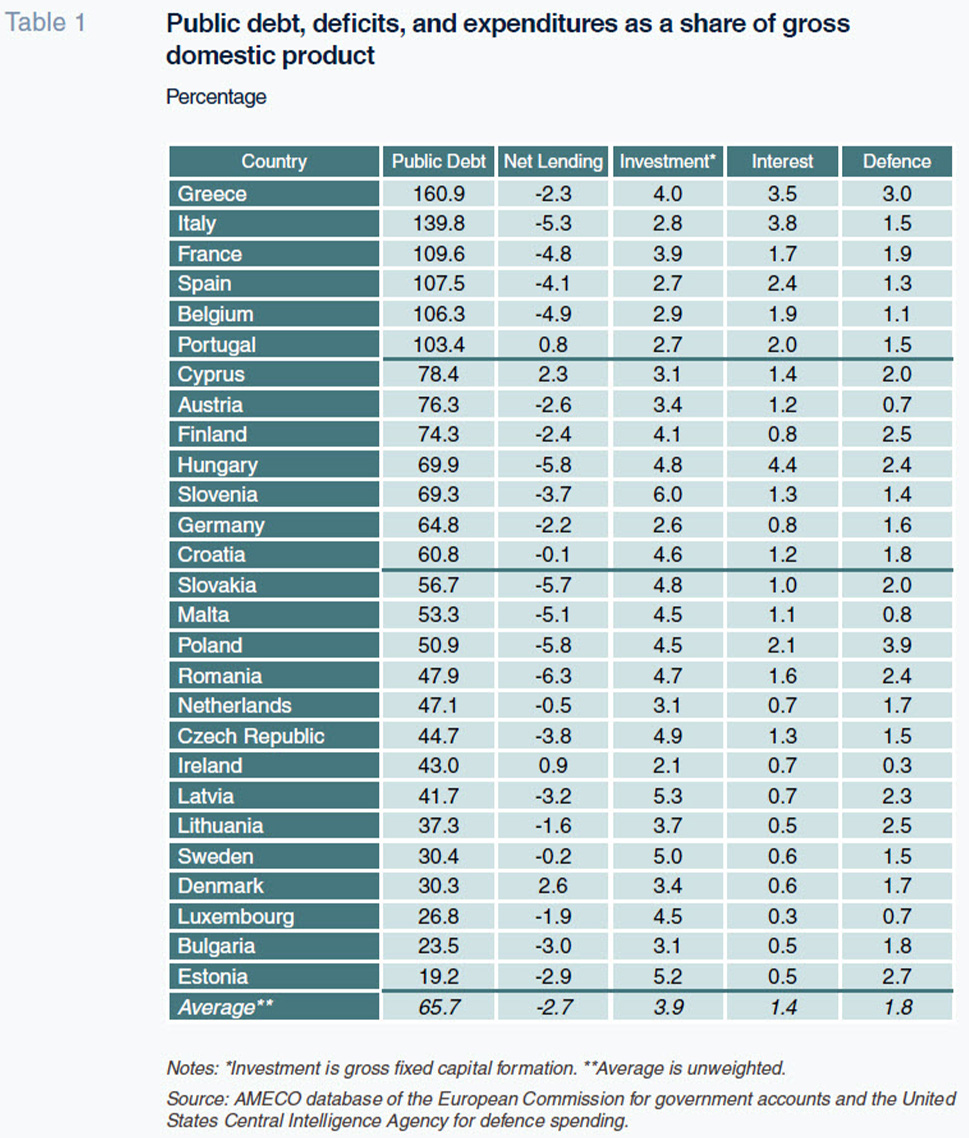

Whether the new framework creates effective incentives for public investment is an open question. The answer will vary on a case-by-case basis. The same question applies to defence spending. And it could also be asked in reference to the concession in the agreement to take the cost of debt servicing into account when looking at the adjustments required over the next three years because of the recent monetary tightening and resulting high interest rates. The reason for this uncertainty is that there is no strong correlation between high debts and high interest charges or low investment and defence spending. This data can be seen in Table 1, which sorts EU member states by debt-to-GDP ratios from high to low and provides data for net lending (which is the opposite of a deficit) together with expenditure on investment, interest payments, and defence.

Greece has a very high public debt, but it has a low deficit, a relatively high level of investment, and a very high level of defence spending – second only to Poland. By contrast, Italy has a lower debt but a higher deficit, a lower level of investment, and a lower level of defence spending. The two countries are similar in terms of interest payments, but otherwise they are very different. France has a lower level of debt and low interest payments, but otherwise falls somewhere in between, with Greek levels of investment but something closer to Italian levels for deficits and defence spending. By some metrics, Spain and Belgium look more like Italy than France, and by others more like France than Italy. This variation is consistent with the emphasis on national ownership and differentiated adjustment processes but raises questions about the effectiveness of common incentives.

The political signalling in the agreement is more straightforward. The agreement makes it clear that fiscal consolidation should be structural and not pro-cyclical, that it should run alongside public investment and not come at the expense of it, that it should support common European policies, and that it should not come at the expense of national security. These qualifications open the door for an important conversation about the collective fiscal stance of the European Union and about the adequate provision of European public goods. The strengthening of the European Fiscal Board also points in that direction. The emphasis is not just on the sustainability of public finances but also, increasingly, on the quality of public expenditure. And while the new framework gives priority to national ownership of any fiscal adjustment process, it also underscores the common interest in macroeconomic policy coordination for the member states of Europe.

Conclusion

The new framework for fiscal consolidation and macroeconomic policy coordination negotiated under the Spanish Presidency constitutes a significant improvement over the existing framework and an important step forward for the European Union. The new arrangement still has technical elements that will attract criticism (see, e.g. Zettelmeyer, 2023). The proposed legislation must also win support from the European Parliament. Nevertheless, the agreement sends a powerful signal about the importance of transparency and credibility in financial markets, the quality of public finances, and the necessary balance between common rules and national ownership. The framework does not diminish the challenges that some member states will face in reducing their debts and deficits, but it does help to ensure that those consolidation efforts will be less pro-cyclical and more realistic.

Notes

References

COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION. (2023a). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Effective Coordination of Economic Policies and Multilateral Budgetary Surveillance and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97 – Mandate for Negotiations with Parliament. Brussels: Council of the European Union, 15874/4/23 REV 4 (20 December 2023).

COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION. (2023b). Proposal for a Council Regulation Amending Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 on Speeding up and Clarifying the Implementation of the Excessive Deficit Procedure. Brussels: Council of the European Union, 15876/4/23 REV 4 (20 December 2023).

COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION. (2023c). Proposal for a Council Directive Amending Directive 2011/85/EU on Requirements for Budgetary Frameworks of the Member States. Brussels: Council of the European Union, 15396/4/23 REV 4 (20 December 2023).

EUROPEAN COMMISSION. (2023). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Effective Coordination of Economic Policies and Multilateral Budgetary Surveillance and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97. Brussels: European Commission, COM(2023) 240 final (26 April).

DARVAS, Z., WELSLAU, L. and ZETTELMEYER, J. (2023). A Quantitative Evaluation of the European Commission’s Fiscal Governance Proposal.

Breugel Working Paper, 16 (18 September).

JONES, E. (2020).

When and How to Deactivate the SGP General Escape Clause. Brussels: Economic Governance Support Unit, Directorate General for Internal Policies, European Parliament, PE 651.378 (November).

JONES, E. (2021). The Coming Debate about European Macroeconomic Policy.

SEFO – Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 10(1), pp. 5-19.

JONES, E. (2022). Recovering from the Pandemic: The Role of the Macroeconomic Policy Mix.

SEFO – Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 11(1), pp. 15-23.

JONES, E. (2023). The Coming Fiscal Adjustment in Europe.

SEFO – Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 12(5), pp. 25-33.

TAMMA, P. (2023). Dutch and Spanish Snap Elections Complicate EU Fiscal Reform.

Politico (13 July).

https://www.politico.eu/article/dutch-and-spanish-snap-elections-complicate-eu-fiscal-reform/ ZETTELMEYER, J. (2023). Assessing the ECOFIN Compromise on Fiscal Rules Reform.

Breugel First Glance (21 December).

https://www.bruegel.org/first-glance/assessing-ecofin-compromise-fiscal-rules-reform

Erik Jones. Director of the Robert Schuman Centre of Advanced Studies at the European University Institute