CoCos and bank resolution: Overcoming March stigma

Given the fact that they are considered loss absorbing instruments in the event of resolution, CoCos have emerged as a very important barometer for measuring confidence in the banking system. Although the bail-in of CoCos during the rescue of Credit Suisse created a stigma that prompted the global CoCo market to collapse, the market has recovered in recent months, marked by a significant rebound in prices and, above all, in issuance activity.

Abstract: Contingent convertible bonds (known as CoCos), which are additional tier 1 (AT1) instruments, have been the instrument of choice for European and Spanish banks looking to reinforce their capital since the financial crisis and, more importantly, the cornerstone of the bank resolution mechanism insofar as they constitute loss absorbing instruments in the event of resolution. As a result, the market for CoCos has emerged as a very important barometer, as or more important than the market for banks’ shares, for measuring confidence in the banking system. That is why this market suffered a rout during the banking crisis of last March and was hit particularly hard by how the Swiss authorities treated Credit Suisse’s CoCo creditors, creating “stigma” around the instrument in general. The way CoCos were bailed in when Credit Suisse was rescued created a stigma that prompted the global CoCo market to collapse. Nonetheless, the market has recovered in recent months, marked by a significant rebound in prices and, above all, in issuance activity.

CoCos as a potential capital reinforcement and/or resolution mechanism

CoCos were first issued by the banks in 2013 in the wake of publication of the Capital Requirements Directive (CRR) and the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) in order to lift their capital ratios, as they compute as additional tier 1 capital (AT1) for regulatory capital purposes.

The key features of these instruments, which qualify them as quasi tier 1 capital (additional tier 1 or AT1), are that they are perpetual securities and are convertible into shares in the event that the issuer sees its common equity tier 1 (CET1) fall below a certain threshold, or trigger.

In general, CoCos are hybrid instruments that combine elements of fixed income and equity securities. They are standard bonds with the added feature that they automatically convert into shares in the event of materialisation of a certain contingency. That means that the bond holder would receive, instead of the face value of its bonds, a specific number of shares, as defined in the issue prospectus.

For contingent convertibles to qualify as AT1 capital for solvency purposes, they must meet the following characteristics:

- They must be issued with no final maturity date and be fully paid in;

- They may be callable and replaceable by their issuer five years after their issuance, subject to express prior authorisation from the supervisory authority;

- Coupon payment gets suspended under certain circumstances, including a shortfall of profits or reserves at the issuer, at the behest of the supervisor if it considers that the payment could undermine the issuer’s solvency, or for other reasons at the issuer’s discretion insofar as they are contemplated in the original prospectus. Suspension of coupon payments does not imply the build-up of the missed payments and is not considered a credit or default event;

- CoCos include special clauses whereby the securities are written down, fully or partially, or mandatorily converted into ordinary shares of the issuer (CET1) in the event of occurrence of a defined trigger event. They likewise feature clauses establishing the conversion price, amount and deadlines in the event that the trigger event occurs.

The possibility of writing down CoCos or converting them into ordinary shares is what makes these instruments a loss absorbing mechanism in either a gone concern (resolution) or going concern situation. Another feature is their priority ranking relative to common shareholders, the matter at the crux of the debate that ensued after the Swiss authorities’ decision when intervening Credit Suisse to write down the troubled bank’s CoCos in full while leaving the shareholders with a minimal claim on the bank.

To analyse this dual loss absorbing capacity (going concern and gone concern), note that these instruments come with two types of clauses, quantitative and qualitative, as regards the triggering of loss absorption.

Under the quantitative clauses, the bonds are automatically converted into ordinary shares if the issuer’s CET1 capital fall to the so-called trigger level, which is established at 5.125% of its total risk-weighted assets under prevailing regulations. That 5.125% is a general regulatory floor under which no issue’s trigger may lie. What commonly happens, however, is that the entities set the trigger at the minimum level of prudential capital required of each, as set by the supervisory authority in the course of the supervisory review evaluation process (SREP).

In addition to this quantitative trigger, CoCo issues also feature qualitative or discretionary triggers. The purpose of these is to enable capital reinforcement in order to retain trust in a going concern context, prior to reaching the point of non-viability, so factoring in the potential time lag in effectively measuring capital levels. The decision as to whether to activate the qualitative CoCo write-down or conversion trigger is up to the relevant authority (supervisory or resolution), generally on the basis of considerations around financial stability and trust, or the need for public support to maintain that trust. In the event of the latter (public support to maintain trust), the Basel III framework permits the full write-down of any CoCos before CET1 capital, something which is not possible in the event that the quantitative trigger is activated.

Indeed, that was the circumstance (activation of the qualitative trigger for stability and public support purposes) that was invoked by the Swiss authorities in imposing the full write-down of Credit Suisse’s CoCos, while its shareholders maintained a minimum claim on the bank via an exchange of their shares for UBS shares under the scope of the merger of Credit Suisse into UBS, a transaction for which public support was pledged.

Impact on CoCos of the Credit Suisse bail-in

Despite the fact that the Swiss authorities’ decision was aligned with the Basel framework, it had a seismic impact on the CoCo market, which interpreted the write-down decision as a breach of a creditor hierarchy perceived as unquestionable in terms of financial logic, creating a degree of stigma around CoCos, which, in addition to financial risks were now seen to present regulatory risk and what was harder to digest, discretionary regulatory risk.

Recall that a CoCo is equivalent from the investor standpoint to a perpetual bond that pays a very high coupon in exchange for which the investor grants the issuer two very different options.

The first is the option to call the bond early, generally at its face value, during any of the call windows (annual or shorter) established from year five after issuance. The issuer’s decision as to whether or not to call the bonds will depend on market conditions, as the banks typically call their CoCos in the event they can place new securities on the market at more attractive terms than the CoCos to be redeemed. This option therefore implies market risk for the investor, a risk that encompasses generic factors (rates, market sentiment, etc.), as well as entity-specific risks (risk premium, capital adequacy, etc.).

The second option extended by a CoCo investor is the option to write down or convert its bonds into ordinary shares in the event of activation of any of the quantitative or qualitative triggers. This second option (a put bought by the issuer) clearly implies tail risk for the investor with low probability of materialisation but highly adverse implications, as the CoCo holder would very likely stand to lose its entire investment in that event.

The existence of both options (and very particularly the second one), coupled with the bonds’ high coupons, makes CoCos extraordinarily asymmetric in terms of investor return scenarios. In normal conditions, they will generate a very handsome return, albeit during an uncertain length of time on account of the issuer’s call options and the possibility of triggering limits on coupon payments (the so-called maximum distributable amount, or MDA). Uncertain above all due to the residual risk of occurrence of a trigger event and the loss of virtually the entire investment.

That significant asymmetry (high coupon under normal circumstances but scope for total write-down in the event of adverse developments), coupled with the intrinsic complexity of their hallmark optionality, is what has characterised CoCos as complex products, not appropriate for retail investors, from the outset.

While the existence of the two options already made CoCos a complex security, the decision by the Swiss authorities injected additional complexity and uncertainty around the product associated with the interpretation (somewhat discretionary and different from one jurisdiction to another) of activation of the principal write-down clause before a shareholder bail-in.

While the existence of the two options already made CoCos a complex security, the decision by the Swiss authorities injected additional complexity and uncertainty around the product associated with the interpretation (somewhat discretionary and different from one jurisdiction to another) of activation of the principal write-down clause before a shareholder bail-in.

The Credit Suisse event happened during the weekend of 19 March. The price of the troubled bank’s AT1s had already been hit particularly hard during the previous fortnight as a result of the regional banking crisis in the US, unleashed by the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. Despite having corrected by 10% before the Swiss regulator took its decision regarding Credit Suisse, the announcement prompted the CoCo market to shed another 8%, for a cumulative correction of over 17% in just two weeks.

Although AT1s had always proven volatile during episodes of risk aversion, this situation was very different, with some observers making apocalyptic predictions that the SNB’s decision would spell the end of the market for CoCos.

Recovery from the stigma: Contributing factors

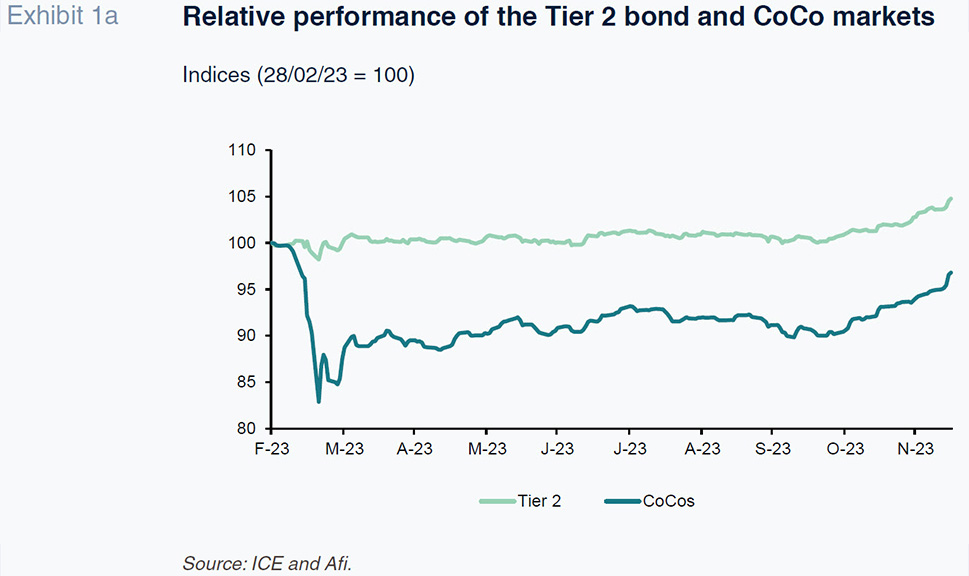

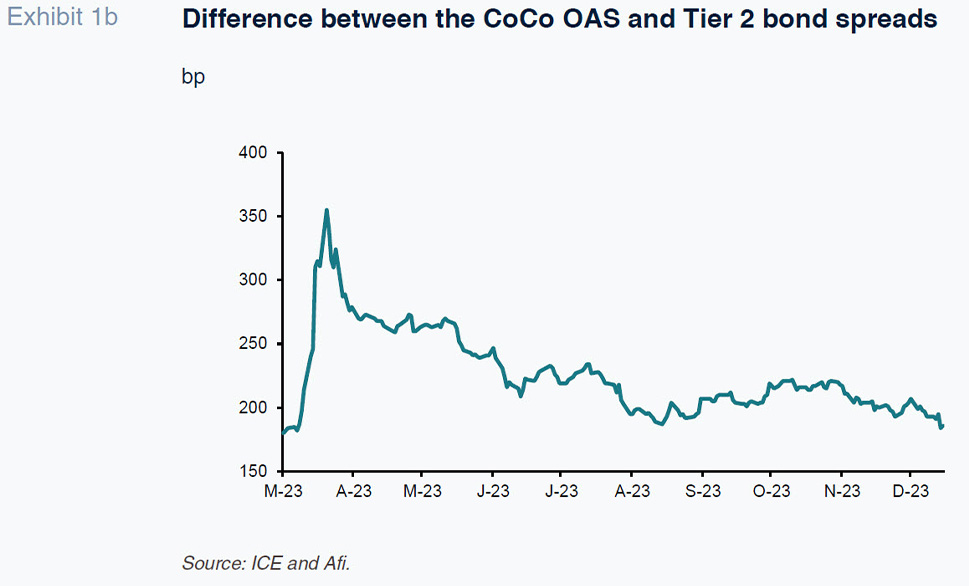

In contrast to those dire warnings, CoCos have since staged a gradual yet intense recovery, punctuated by a year-end rally (when all risk asset classes performed exceptionally well), with the credit spread between CoCo and tier 2 instruments returning to pre-March crisis levels and, in terms of prices, to just 3% below that threshold (a gap that is attributable to the increase in risk-free rates).

Several factors have contributed to the gradual recovery in CoCos, enabling this asset class to shake off the stigma generated in March:

Firstly, following the decision by the Swiss authorities (SNB), both the ECB and the Bank of England issued releases suggesting that AT1 holders should only absorb losses after shareholders have lost their entire investment. That was a statement of intent: the regulators realised that for the instrument to survive, the SNB’s decision could not be seen by investors as standard practice.

In parallel to the support received from the supervisory authorities in other European jurisdictions (ECB and BoE), it was vital for the market to witness all entities with call windows looming in the following quarters being able to exercise those options. Expectations were exceeded in that respect. While the market believed that some of the bigger banks with stronger credit ratings would be able to exercise their call options, there were considerable doubts about the less creditworthy entities’ ability to do so. However, virtually all the banks have since exercised their call options, sending investors a very positive message in the process. By doing so, the banks exhibited their commitment to bowing to market discipline: to exercise their call options they had to issue new CoCos. As a result, market supply did not shrink. What the banks did do was to subject themselves to market scrutiny by accepting the terms of new issues rather than clinging to their existing deals. Moreover, to call their CoCos, the issuers had to first get authorisation from the supervisor, providing a further confidence boost.

The above developments are intrinsically tied to the momentum observed in the primary market. While that market initially closed to new issues as it awaited a reduction in credit spreads and recovery in confidence, it was not too long before it reopened. The first issues took place in June, when BBVA and the Bank of Cyprus tapped the CoCo market. The Bank of Cyprus issue was particularly surprising as it signalled market appetite for issuers with very diverse credit risk profiles. Demand was very strong for those first issues, a trend that continued throughout the second half of 2023. One of the highest-profile issues was that of UBS, which, despite the events earlier in the year, issued 3.5 billion dollars of CoCos that were 10 times oversubscribed in November (Demand: 36 billion dollars).

Lastly, it is clear that the improvement in the banks’ fundamentals, marked by extraordinary profit growth, has helped matters. Indeed, that has had two important consequences: (i) virtually all of the issues reaching the market since March correspond to the refinancing of called issues (i.e., scant net new issuance); and, (ii) some CoCos have been cancelled without replacement, as the banks have been able to meet their capital requirements via organic capital generation.

In short, the recovery in the AT1 market is very good news for the banking sector. CoCos have been a crucial tool in bank recapitalisation, especially at times when raising capital by issuing shares would have implied hefty shareholder dilution, further undermining the banks’ share price performance. As a result, this instrument should continue to give the banks flexibility when planning their capital strategies.

References

COELHO, R., TANEJA, J. and URBASKI, R. (2023). Upside down: when AT1 instruments absorb losses before equity. BIS-FIS Working paper, September 2023.

EUROPEAN BANKING AUTHORITY (EBA). (2023). European Banking Authority Risk Assessment Report. December 2023.

PEROSSI, E. (2023). The Swiss authorities enforced a legitimate going concern conversion. CEPR/VOXEU columns, March 2023.

Ángel Berges and Salvador Jiménez. Afi