Fiscal sustainability of Spain’s local governments: Targeted weaknesses within overall strength

While Spain’s local governments have achieved balanced budgets on the whole, a number of municipalities present fiscal sustainability issues. Addressing these long-standing challenges will require extraordinary measures to improve structural solvency.

Abstract: While as regards to fiscal performance and the achievement of financial equilibrium, Spain’s local governments on aggregate have been the best performing level of the Spanish administration, a more granular assessment reveals vast differences across municipalities. Over 100 municipalities face structural financial challenges, primarily recording too high a level of public debt for too long a time frame. Restructuring public finances across these heavily indebted municipalities will requires implementing policy measures aimed at restoring fiscal sustainability and a balanced budget. The deferral of debt service payments, the main policy tool formulated by the central government in recent aid mechanisms, has proven ineffective to resolve the current fiscal imbalances at the local level and has even at times exacerbated the problem. To tackle the problem identified, new solutions are needed. The local authorities should be held jointly responsible for the restructuring process by making them take the steps needed to balance their budgets over time in a sustainable manner.

Background

Within the Spanish public administration, from a budgetary stability standpoint, the local government subsector has been the best performing since the passage of the Budget Stability and Financial Sustainability Law (Organic Law 2/2012) on 27 April 2012. Except for 2022, the local governments have presented a budget surplus consistently since 2012. 2022 was conditioned by a negative definitive settlement in respect of 2020.

Despite the overall favourable assessment, there is a small group of municipalities in a far more precarious situation. Already in December 2017, Spain’s Independent Fiscal Institute, AIReF, having evaluated a group of 18 local authorities with more than 20,000 inhabitants, noted that nine of them presented “structural and grave financial sustainability issues”. For those authorities, AIReF recommended that the Ministry of Finance and Civil Service convene and head up a committee of experts, as contemplated in Articles 25.2 and 26 of the above-mentioned Budget Stability and Financial Sustainability Law, to analyse the root causes and propose suitable solutions.

In this paper, we review the cohort of local authorities that could be considered to present structural sustainability problems in order to determine their defining characteristics and analyse the source of their problems. Lastly, we propose a solution to the situation documented based primarily on the nature of the problematic councils in question and measures taken by a number of authorities in the past in similar situations.

Profiling sustainability challenges across municipalities

The municipalities considered to present sustainability issues are those with the following characteristics:

- Firstly, they are overly indebted (their debt is equivalent to over 110% of current revenue, which is the limit defined in applicable regulations as the threshold beyond which the local authorities cannot arrange any new debt).

- Secondly, they have surpassed that threshold for a considerable number of years, demonstrating an inability to pay down their borrowings.

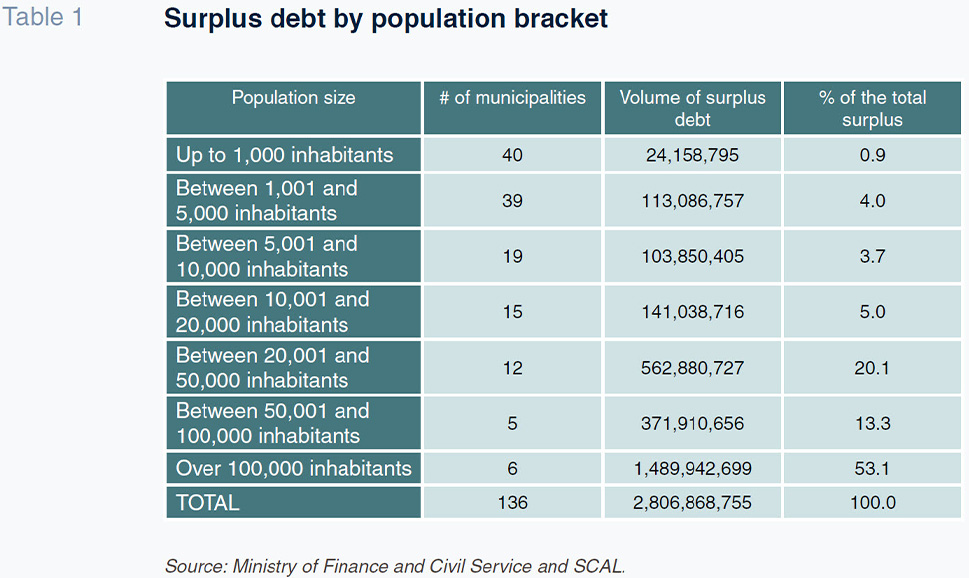

On the basis of the above definition and using the most recent budget settlement available (that of 2021), we arrive at a cohort of 136 financially-compromised municipalities.

Analysing the characteristics of these municipalities’ treasuries in order to determine whether they share patterns that could point to structural factors leading to these predicaments, we found that:

- The biggest number of municipalities with debt equivalent to more than 110% of their current income is found in the population bracket encompassing municipalities with up to 1,000 inhabitants, at 40, followed by those with between 1,001 and 5,000 inhabitants, a bracket containing a further 39 municipalities.

- The highest population brackets present the lowest number of local authorities with debt in excess of the legal threshold:

- In the bracket with between 20,001 and 50,000 inhabitants: 12 municipalities.

- In the bracket with between 50,001 and 100,000 inhabitants: 5 municipalities.

- In the bracket with over 100,000 inhabitants: 6 municipalities.

Nevertheless, the above distribution of the over-indebted municipalities is consistent, and directly related, with the number of local authorities comprising each population bracket. As a result, there is no bias in the effect that population size has on over-indebtedness.

If, however, within this analysis we look at the amount by which the affected authorities are overly indebted, we observe that the biggest excesses are found in the municipalities with more than 100,000 inhabitants. The amount of debt incurred beyond the legal threshold stands at 2.81 billion euros on aggregate, of which over half (1.49 billion euros) is owed by municipalities with over 100,000 inhabitants.

The volume of surplus debt increases considerably in the population brackets with more than 20,000 inhabitants.

This phenomenon is primarily attributable to the size of their municipal budgets as the average volume of debt per inhabitant is actually higher in municipalities with up to 1,000 inhabitants.

Indeed, the municipalities with up to 20,000 inhabitants account for just 14% of the surplus debt, whereas they represent 83% of the affected authorities.

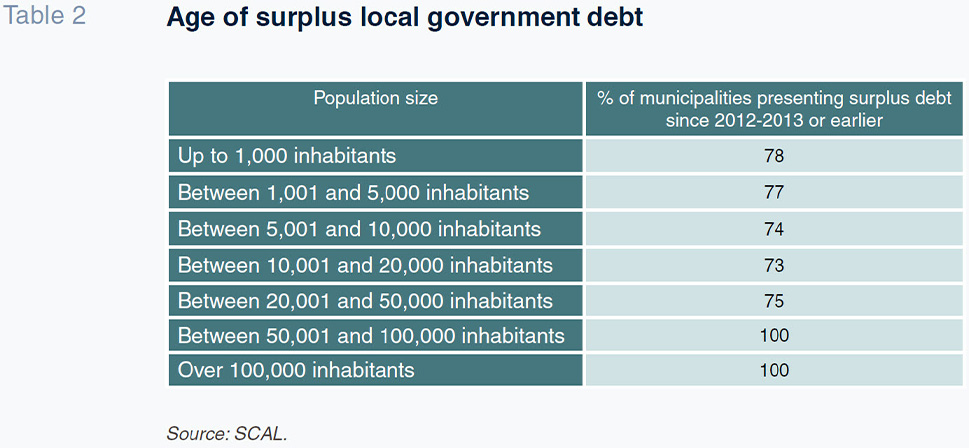

- Elsewhere, an analysis of the length of time the identified municipalities have presented surplus debt reveals a sharply structural phenomenon, as most of it stems from state financing mechanisms put in place in 2012 and 2013 to reduce trade debt in the public sector.

Specifically, that debt came about fundamentally as a result of the following regulations:

- Royal Decree-Law 4/2012 (24 February 2012) determining certain reporting obligations and procedures for establishing a mechanism to finance supplier payments by local authorities. This regulation allowed local governments to cancel outstanding debts with their suppliers as a result of works contracted, supplies procured or services rendered that had been invoiced prior to 1 January 2012. As a result, trade debt was turned into financial debt.

- Royal Decree-Law 8/2013 (28 June 2013) on urgent measures for tackling non-performance in local government and supporting local entities with financial problems. The purpose of this piece of legislation was to create a temporary and extraordinary mechanism to help local governments reduce accumulated trade debt. As set down in that piece of legislation, the idea was to set the trade debt counter at zero prior to implementation of the e-invoicing system, book-keeping, average payment term requirements and, ultimately, the Budget Stability and Financial Sustainability Law controls. Once again, this measure had the effect of increasing the local authorities’ financial debt in order to decrease the sums owed to suppliers.

This means, in short, that the identified municipalities’ debt problem is an entrenched issue for which the specific measures rolled out in the past have not been effective and have even led to a sharp increase in their pool of debt.

Moreover, the budget structure of a good number of the municipalities in this situation in 2021 suggests they are not in a position to deleverage.

The situation outlined and its characteristics yield two noteworthy conclusions:

- For the most part, the local authorities’ surplus debt is structural, as it has been in place for over a decade.

- The borrowings taken on under the above-mentioned financing mechanisms revealed that the entities with more than the permitted levels of debt had for a long time been presenting budget imbalances which ultimately led them to accumulate excessive trade debt. For the most part, those imbalances remain intact at present, so that the troubled authorities do not have the ability to generate enough gross savings to pay down their debt.

Here it is worth noting that the trade debt payment mechanisms were mandatorily accompanied by financial restructuring plans by the local authorities in question. The Ministry signed off on the measures included in the planning documents and subsequently monitored the authorities performance. However, time has shown – with most of the affected authorities continuing to present surplus debt – that the system for controlling execution of those restructuring plans has been ineffective at restructuring the troubled local treasuries.

Conclusions

Although the local government subsector presents broad financial equilibrium on aggregate, over 100 municipalities face structural financial challenges. The authorities in question hold too much debt and have done so for too long.

Restructuring the finances of these troubled municipalities requires designing and implementing measures aimed at restoring a sustainable, balanced budget. The deferral of debt service payments, the main tool used by the government in recent aid mechanisms, has proven ineffective in these situations and has sometimes exacerbated underlying issues.

To tackle the problem identified, new solutions are needed. Here it is worth noting that other countries have successfully pursued budget rebalancing measures in the past, as have a number of regional governments in Spain, including those of the Canary Islands, Andalusia and Valencia.

The local authorities should be held jointly responsible for the restructuring process by making them take the steps needed to balance their budgets over time in a sustainable manner.

They should have to commit to complying with a series of targets around basic metrics:

- Positive gross savings.

- The non-generation of extra-budgetary debt.

- A year-on-year change in non-financial spending within the percentage stipulated by the central government.

- The non-generation of a budget deficit in national accounting terms.

Ana Aguerrea. Afi