Central banks: Between a rock and a hard place?

Financial turbulence has been easing in recent weeks, reflecting the idiosyncratic nature of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Credit Suisse (CS) failures and the adequacy of the responses by the affected central banks, although some risks remain. Central banks will face an increasingly challenging context as they seek to restore price stability, while minimising outbreaks of financial stress.

Abstract: Financial turbulence has been easing in recent weeks, reflecting the idiosyncratic nature of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Credit Suisse (CS) failures and the adequacy of the responses by the affected central banks, although some risks remain. Monetary tightening led to a more than 4pp increase in official rates worldwide in 18 months, a movement with no precedent in recent decades in terms of its speed or intensity. Such pronounced and intense rate increases constitute a steep stress test for banks with solvency and/or liquidity weaknesses. The good news is that the fallout has been fairly limited. The US authorities have managed to: protect deposit holders; minimise risks for taxpayers; and, curtail the loss of confidence in the regional banks which in many states are key for monetary policy transmission. Questions remain as to where the next hotspots of instability could lie, with potential high-risk areas including: commercial real estate valuations; hedge fund leverage; loans by US banks to non-bank financial institutions; liquidity at certain life insurers in the US; and, structural weaknesses in some mutual fund categories. Thus, we need to be aware of the difficulties that will face the central banks as they near the end of their rate tightening process, as the complexity of restoring price stability while minimising outbreaks of financial stress is set to increase.

Introduction

The weak global economy is entering a new phase in the search for new equilibriums following the succession of shocks sustained in recent years. In that transition, for the first time in the last decade, the central banks’ dual mandate of controlling inflation and ensuring financial stability will be put to the test with the recent spate of intense tightening beginning to spark hotspots of tension. The Silicon Valley Bank crisis and its reverberations in Europe (Credit Suisse) have not been a game changer but have fired a warning shot about the potential price of the final phase of monetary normalisation in terms of financial stability. Also, this has been a signal that financial system supervision and regulation are facing new challenges nearly a decade on from the changes introduced in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. The good news is that a few months on from the onset of the bank troubles in the US, the financial stress appears to be relatively under control and, although it is too soon to estimate its impact on economic activity, we are far from looking at a credit crunch.

The end of the beginning?

The Global Financial Crisis (2008-2012) widened the central banks’ remit, adding financial stability [1] to the traditional inflation target, a prerequisite for keeping prices in check by ensuring that a key monetary policy transmission channel can do its job properly. Until this year, after a long period of extraordinarily expansionary monetary policy, there had been no contradictions between the two targets. However, the intense tightening undertaken since early 2022 would put the compatibility of the two policy goals to the test. In theory, macroeconomic instability should be addressed using traditional monetary policy tools and transmission channels, while financial instability should be tackled via macroprudential regulation and supervision, coupled with suitable management of the discount window liquidity facilities. However, when confidence in the system is lost, the tools and targets get mixed up, as was evidenced once again in the US last March.

The source of the tension was the more than 4pp increase in official rates worldwide in 18 months, a movement with no precedence in recent decades in terms of its speed or intensity. With monetary policy already in contractionary territory, when the rate tightening process is complete,

[3] the central banks will have hiked rates by more than twice the average during contractionary cycles in recent decades (450

versus 200 basis points). Something not even the economic agents or financial markets were prepared for after a decade of extraordinarily expansionary monetary policy.

[5] In December 2021, monetary policy expectations suggested barely any possibility of the central banks raising rates in 2022, despite clearly ominous signals regarding inflation.

Such pronounced rate increases constitute a steep stress test for banks with weaknesses in their business models that have subsisted on account of inadequate regulations/supervision. SVB was a case in point, having increased its assets three-fold in three years thanks to growth in deposits by tech firms and the investment of that liquidity in long-term public debt with no hedges whatsoever. Once the central banks shifted their policy tack, the American bank began to pile up sizeable unrealised losses. Doubts about the bank’s liquidity and solvency triggered a sharp run on deposits, which were highly concentrated and very unstable (95% of the deposit balances were above the 250,000 dollar threshold for coverage by the deposit insurance scheme). The role played by the social media was another catalyst, with 40 billion dollars of deposits withdrawn in just one day (25% of the total). The intensity of the run was eight times that observed at the height of the financial crisis of 2008.

To prevent contagion, the US Treasury and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) announced they would guarantee all of the bank’s deposits and the Federal Reserve presented a new one-year liquidity facility (Bank Term Funding Program) which can be discounted using Treasury securities valued at par as collateral. Another three banks also had to be intervened: Silvergate and Signature Bank (both with significant exposure to crypto currencies) and First Republic Bank. The contagion in Europe was concentrated at Credit Suisse, a bank that had been struggling with credibility issues for years and which had seen 68 billion dollars of deposits withdrawn in the first quarter of the year. In the end, it too had to be intervened and sold to UBS, giving rise to a controversial ranking of loss absorption by shareholders versus bondholders.

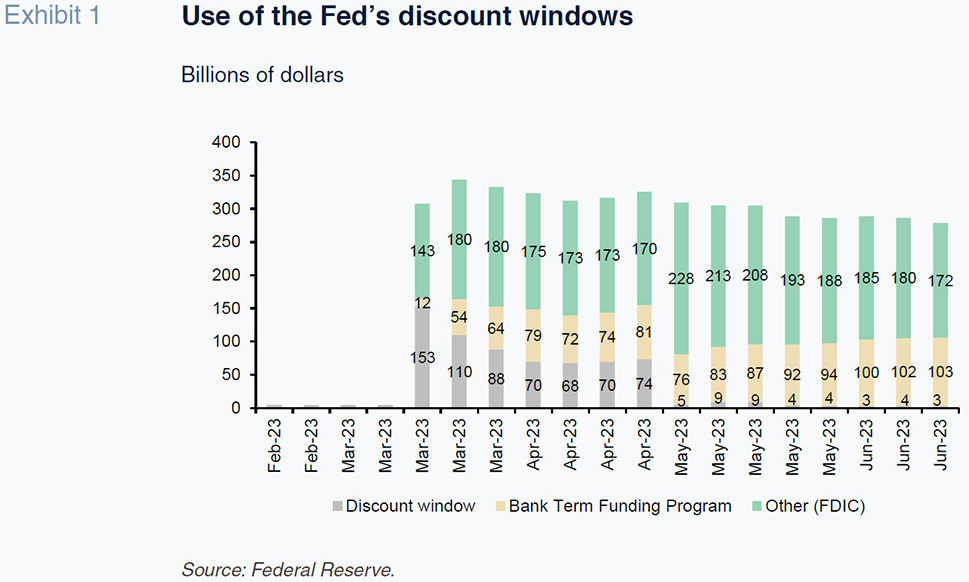

With the purchase of First Republic by JP Morgan at the start of May, the perception is that the situation is reasonably under control thanks to the rapid intervention and sale of the affected entities and the Fed’s actions to provide liquidity buffers to the banks. Since the second half of March, the American banks have been obtaining 300 billion dollars via the Fed’s facilities (Exhibit 1), with use of those discount windows actually beginning to taper in recent weeks, suggesting that the tension is gradually beginning to ease.

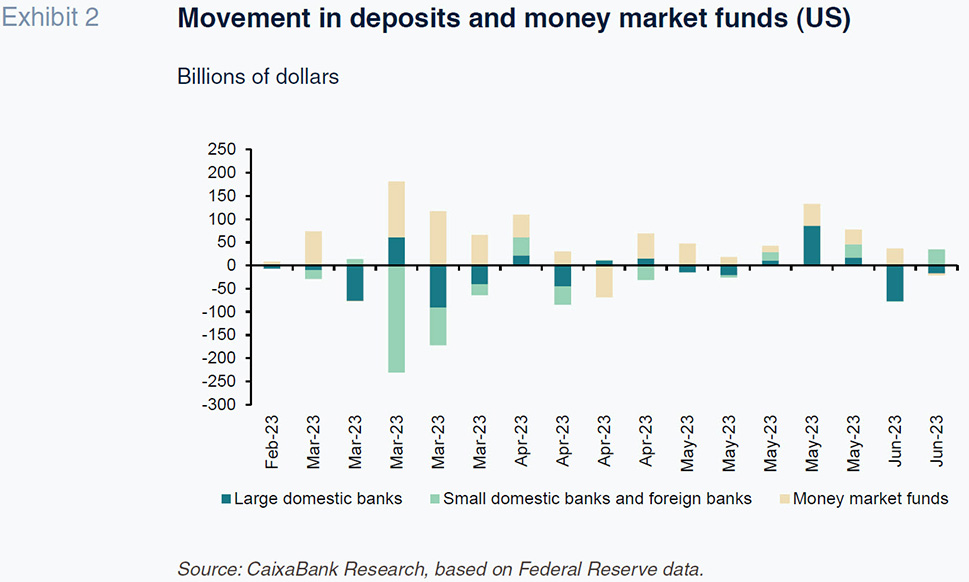

Likewise, the recent trends in the regional banks’ share prices and in deposit movements within the American financial system are consistent with stabilisation of the crisis. In fact, only at the height of the turbulence (mid-March) did the regional banks lose sizeable volumes of deposits to the major US banks (Exhibit 2).

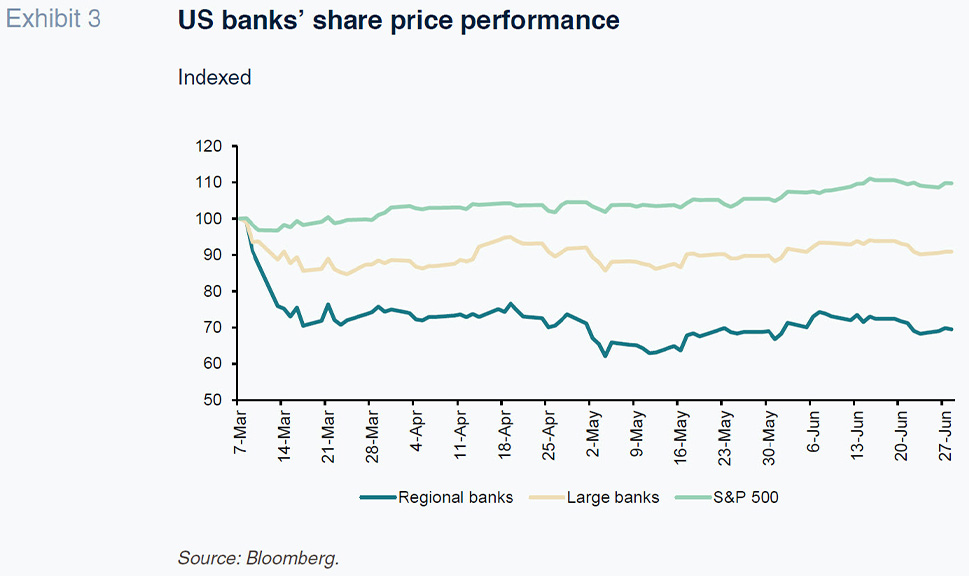

Since then, the movements have been limited, the only noteworthy development being a logical shift by retail customers into money market funds to take advantage of the high return on short-term bills. Therefore, the US authorities have managed to: protect deposit holders; minimise risks for taxpayers; and curtail the loss of confidence in the regional banks which in many states are key for monetary policy transmission purposes (Exhibit 3).

In fact, having initially paused their rate increases, in June, the members of the FOMC revised their guidance for year-end rates upwards by 50bp and the market is no longer discounting rate cuts after the summer, evidencing how, in the balance between economic and financial stability, attention has returned to the trend in inflation in the near-term. Which is ultimately a good sign.

Therefore, one quarter on from the first episode of financial instability triggered by monetary tightening, [8] aware that the effects of the rate increases will remain a threat to the most fragile parts of the financial system and markets for a significant period of time, the situation looks to be reasonably under control. The main conclusions from the March events are, therefore:

- The affected banks (SVB, Signature, etc.) were outliers with very fragile business models as a result of managerial shortcomings.

- Once again, it has become clear that the financial chain is only as strong as its weakest link, spelling the need for stringent supervisory and regulatory controls irrespective of entity size. To be able to anticipate weaknesses such as that of SVB requires the use of qualitative preventive mechanisms that enable business model restructuring.

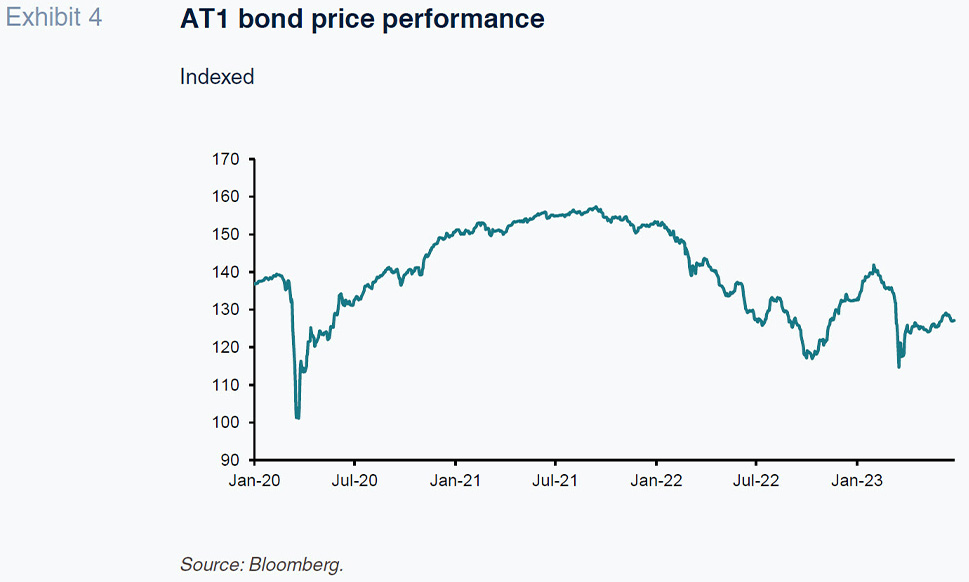

- Contagion beyond the US has been limited, [9] except for the failure of Credit Suisse, which had been suffering from credibility problems for some time. The AT1 bond market (contingent convertible bonds or CoCos) has even been recovering, having been seriously disrupted when investors in Credit Suisse’s securities saw all of their value wiped out ahead of the bank’s shareholders, [10] altering the usual loss absorption hierarchy. AT1 bond prices have recovered by more than 10% from their lows of 20 March and are now just 4% below pre-crisis levels.

- A decade on from the last financial crisis, supervision and regulation needs to be adapted for new challenges, including the role of social media. The speed with which crises of confidence can spread has intensified, which means that the speed and flexibility of the resulting interventions must also be reinforced. In the third quarter of this year, the US regulators are slated to announce new capital requirements in the US. [11] Meanwhile, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) acknowledged in its last Stability Report that the Credit Suisse crisis has highlighted that: i) the liquidity buffers were insufficient to cover such an intense run on deposits; ii) the AT1 triggers were inadequate as they were not activated even when the bank’s financial health was already very precarious; and, iii) the regulatory capital buffer did not work as a security net.

- The financial instability of March has brought the role of deposit insurance schemes back into the limelight. The FDIC report on the March crisis recalls that in the US, some 46.6% of deposits are not insured under the current threshold (250,000 dollars). The FDIC’s reform proposals include:

- Increasing the limit on insured deposits from 250,000 dollars to the level deemed opportune (limited coverage).

- Insuring all deposits regardless of their size (unlimited coverage), which could create a moral hazard problem.

- Keeping deposit coverage at current levels (250,000 dollars) and also covering all transaction deposits (targeted coverage). The FDIC´s preference is this last option although it would be hard to define what is a transaction deposit (held to transfer monetary value) rather than a deposit held for savings (store of value).

The last question is where the next hotspots of instability could lie. In its last Financial Stability Report, the Fed detected the following potential sources of fragility: commercial real estate valuations, hedge fund leverage, loans by US banks to non-bank financial institutions; liquidity at certain life insurers in the US, and structural weaknesses in some mutual fund categories.

Fallout from the financial instability

The biggest question mark in such a changing world is how an episode of financial instability such as that observed in March could alter the monetary policy transmission mechanisms, affecting the delicate balance facing the central banks of having to reconcile growth, inflation, and financial stability targets. Indeed, having stuck with their original rate hike decisions in March (backtracking would have undermined confidence), the central banks then took some time until June to assess the effects of the regional bank crisis in the US on growth by either pausing their tightening (Fed and Bank of Canada, among others) or reducing their intensity (ECB).

The channels by which an episode of financial stress affects growth are confidence, financial conditions, and credit standards. With respect to confidence, neither household nor corporate expectations appear to have been dented at any stage. The rapid response by the Federal Reserve and FDIC, stepping in to insure all of the deposits of the first banks to be affected, swiftly limited the damage to confidence. That is evident in the stability observed in deposit flows from the American regional banks to their larger counterparts (Exhibit 2 above).

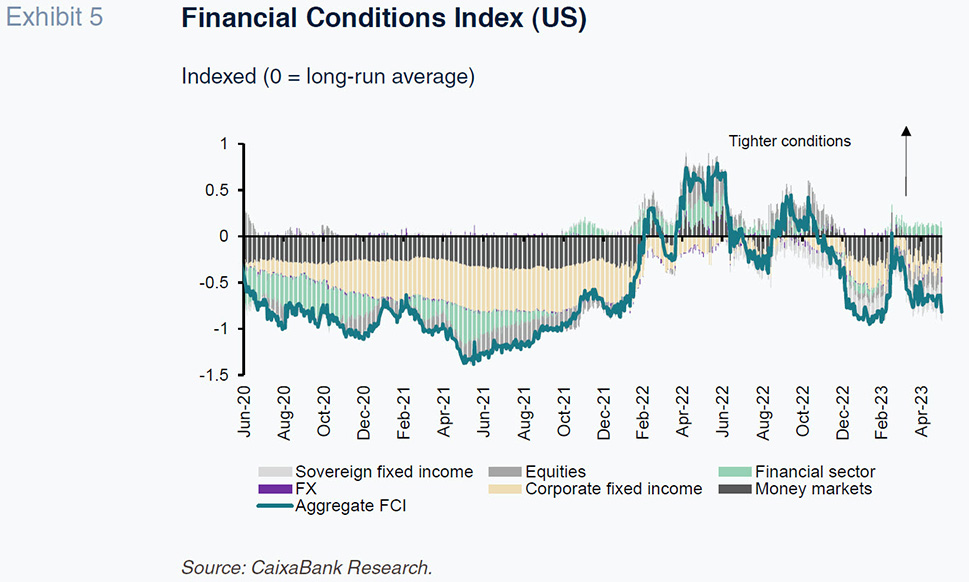

Elsewhere, the crisis had the effect of tightening financial conditions in the eurozone and US alike (Exhibit 5). [13] The metrics suggest, however, that the deterioration was short-lived and far less intense than during previous episodes. In fact, the tightening was far less intense than during other times of uncertainty in recent years, such as when the Russian forces invaded Ukraine. And some of the tightening has since reversed, particularly in the US. By component, the revision of interest rate expectations and attendant drop in short-term sovereign bond yields partially offset the spread widening observed in both corporate bonds (particularly those with lower credit ratings) and interbank rates and the correction in the banks’ share prices. In general, however, at no time did the more fragile segments of the market appear to be under threat and the central banks were not obliged to intervene, other than to reinforce the odd discount window lending programme in the US and enhance the provision of liquidity through the standing US dollar swap line arrangements, thanks to coordinated action by the Fed, ECB, Bank of Canada, Bank of Japan and Swiss National Bank.

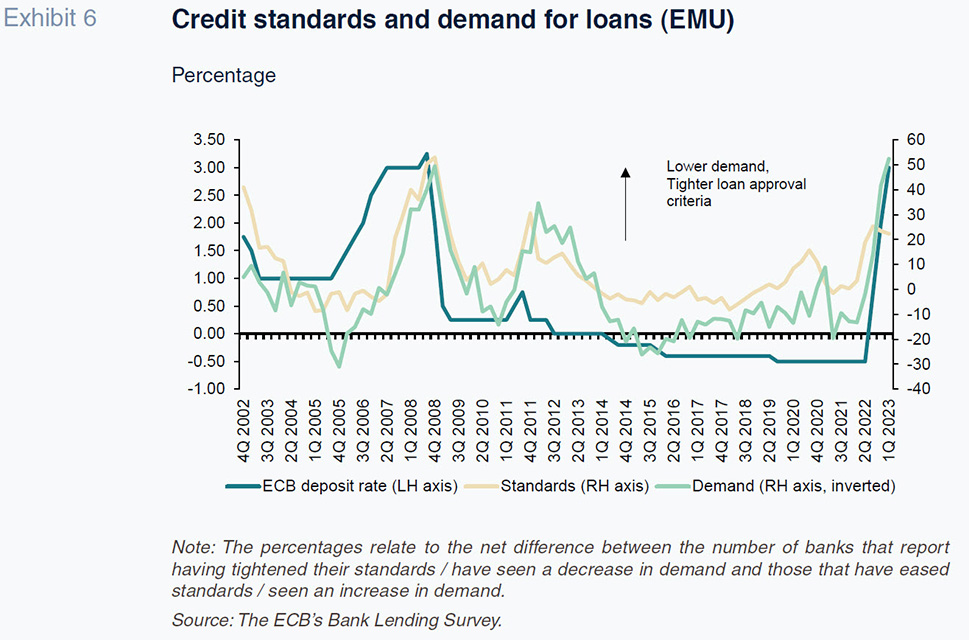

Lastly, the rate increases by the Fed and the ECB (+500bp and +400bp, respectively) are already translating into tighter loan approval standards and weaker demand for credit, foreshadowing cooling in the lending channel. That is borne out by the most recent banking surveys conducted by the Fed and the ECB (the BLS in Europe and the SLOOS in the EU), in which the first-quarter 2023 figures reflect the accumulated tightening (Exhibit 6).

It is important to underline, however, that the trend has not intensified since the March financial crisis on either the supply or demand side, suggesting continuity of the previous momentum. It is also worth noting that monetary tightening is having a bigger impact on demand for financing than on the supply of credit. As a result, the situation bears little similarity to the credit crunch observed in many countries during the 2008-2012 crisis, evidencing the international financial system’s very different solvency and liquidity situation. In short, in a context of higher interest rates, tighter loan approval criteria and lower demand, lending volumes are bound to cool. But nothing out of the ordinary or different from what the central banks will be expecting from one of the main monetary policy transmission channels.

Conclusions

Financial turbulence has been easing in recent weeks, reflecting the idiosyncratic nature of the SVB and CS failures and the adequacy of the responses by the affected central banks, although some risks remain. Such pronounced and intense rate increases constitute a steep stress test for banks with solvency and/or liquidity weaknesses. The good news is that the fallout has been fairly limited. However, we need to be aware of the difficulties that will face the central banks as they near the end of their rate tightening process, as the complexity of restoring price stability while minimising outbreaks of financial stress will only increase.

Notes

The ECB defines financial stability as “a condition in which the financial system is capable of withstanding shocks and the unravelling of financial imbalance. This mitigates the prospect of disruptions in the financial intermediation process that are severe enough to adversely impact real economic activity”.

As the BIS has recently reminded us, a better balance between monetary and fiscal policy would make the two targets more compatible.

After the latest moves by the Bank of Canada, Bank of England and the ECB, and the latest guidance from the members of the Federal Reserve’s FOMC, we are likely to see rates rise a further 50 basis points before reaching their terminal rate.

However, the starting point on this occasion was much lower.

The first warning came in September 2022 with the British debt crisis and its effects on the pension funds.

Credit Suisse had been suffering from reputational issues, had sustained significant losses on defaulted transactions (Archegos and Greensill Capital) and had a deposit base that was scantly covered by the deposit guarantee scheme.

The state guarantee amounts to 9 billion euros and the Swiss National Bank has provided the new entity with a 100-billion-euro liquidity facility. The merger took place over a weekend, before the Asian markets opened, taking advantage of the flexibility provided in Article 185 of the Swiss Constitution.

In the case of the debt crisis in the UK in September 2022, the trigger was the announcement of a fiscal package that considerably undermined the health of the country’s public finances.

No comparison with the events of 2008 and the contagion triggered by the CDOs.

The eurozone authorities rapidly clarified that a similar treatment of AT1 bondholders would not have been possible in the EU.

The key will be the changes made to how the 100 mid-sized entities are regulated (the 20 largest are supervised directly by the Fed). The mid-sized banks have between 10 and 150/200 billion dollars of assets, and they provide one-third of the system’s loans.

The total value of the system’s exposure to CRE is 5.6 trillion dollars, with the weakest part (offices in Central Business Districts (CBDs)) accounting for 25% of that total.

Monetary tightening first impacts financial conditions and, later, affects growth and inflation.

In contrast to what happened in March and April 2020.

References

BIS. (2023). Annual Report 2023.

FEDERAL RESERVE. (2023). Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank, April 2023.

MORRÓN, A. and MURILLO, R. (2023). Is monetary policy managing to cool economic activity? A first assessment A first assessment. Caixabank Research Monthly Report (June 2023).

SNB. (2023). Financial Stability Report 2023.

José Ramón Díez Guijarro. CUNEF