Autonomous regions leading

decline in debt servicing costs

Although average funding costs have gone down for all levels of the Spanish public administration, the autonomous regions have seen the largest reduction, primarily explained by the favourable financing arrangements set up by the State. However, autonomous regions should gradually return to market finance to support a constructive outlook for overall public debt sustainability.

Abstract: The ECB’s unconventional monetary policy measures, namely its public debt purchase programs, have helped euro area governments reduce their average cost of debt, while increasing maturities. In the case of Spain, Treasury yields have come down from an average of 4.07% at the end of 2011 to 2.59% at present, while average maturity has increased from 6.3 years at the end of 2013 to 7 years today. The favourable evolution of debt servicing costs in Spain has been most pronounced across the autonomous regions primarily for three reasons: high degree of reliance on the favourable terms of the State funding mechanisms, high proportion of refinanced loans; and, general inability to take advantage of extending maturities. While State financing support schemes have reinforced the stability of regional debt during a challenging context, it is precisely those autonomous regions who have most benefitted from these schemes that may face the greatest strain throughout the process of monetary policy normalisation. For this reason, a gradual return by the autonomous regions to market finance would be the optimal path for overall public debt sustainatility going forward.

The ECB’s unconventional monetary policy has driven down risk-free interest rates in the euro area to record lows

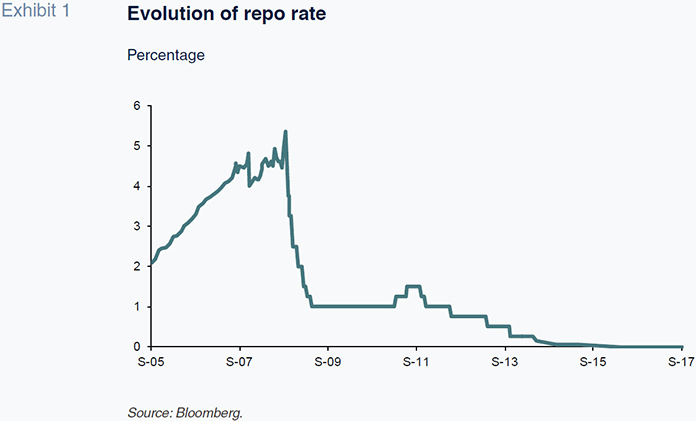

The European Central Bank’s (ECB) objective is to safeguard the value of the euro and maintain price stability. Traditionally, the central bank has implemented expansive monetary policy by deploying conventional measures such as interest rate cuts (MRO), adjusting reserve requirements or modifying standing facilities. However, in order to combat deflation and stimulate GDP growth, the ECB also began to implement non-conventional monetary policy from 2008 onwards through the provision of unlimited liquidity (full allotment) to financial institutions and via debt purchase programmes – both public, as part of the Securities Market Programme (SMP), and private debt under the Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP). In both cases, the purchases were carried out in the secondary market, albeit with the ECB sterilising SMP purchases through auctions to drain liquidity.

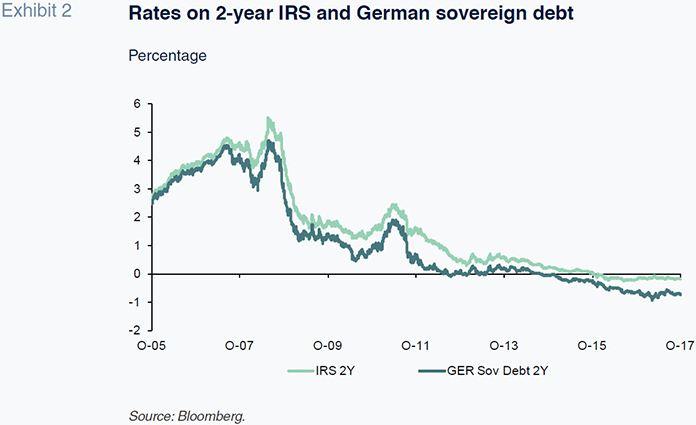

However, the ECB’s Governing Council meeting on January 2015 marked a turning point. The ECB announced that it would launch a programme of public debt purchases through the PSPP (Public Sector Purchase Programme) in response to a continued deterioration in inflation expectations despite implementing the above-mentioned measures. These purchases are not being sterilised, and are swelling the ECB’s balance sheet to over 1.7 trillion euros by October 2017. The measures have also had a concurrent and notable impact on the euro area’s risk-free interest rate, pushing down rates on a two-year interest rate swap (IRS) to negative territory from October 2015 onwards and driving down equivalent German sovereign debt to around -1%.

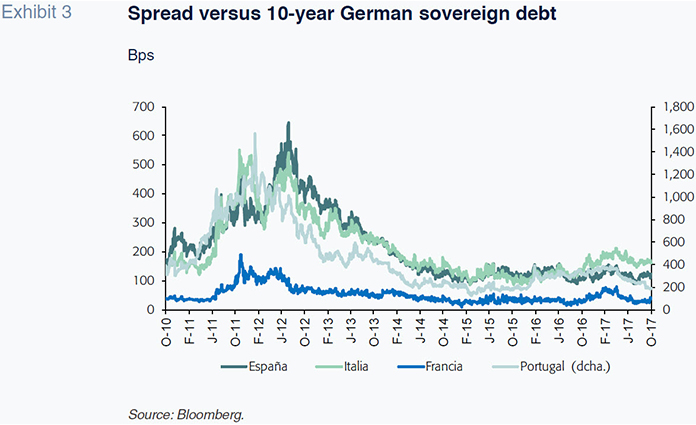

The different measures adopted by the ECB have also led to a compression of credit spreads in different euro area countries

The measures implemented by the ECB have not only led to a reduction in risk-free rates but also in credit spreads, spurring a substantial reduction in financing costs in peripheral economies. While Spanish and Italian 10-year sovereign debt traded at yields of over 7% at the height of the uncertainty in 2012, over the last two years, equivalent-tenor debt has been trading at 1.50% and 1.75% respectively. The reduction has been equally significant in Portugal with the credit spread relative to the German Bund now below 200bps. The reduction in the financing costs of peripheral economies has been crucial to alleviating concerns around the sustainability of public debt in these countries, which were further accentuated by the sharp spike in debt-to-GDP ratios.

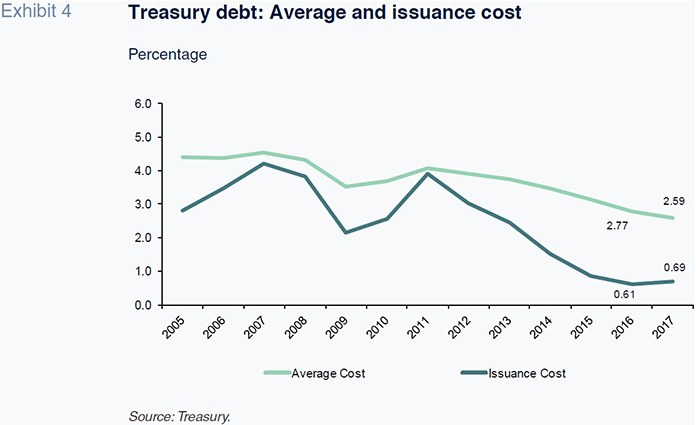

The Spanish Treasury has not only reduced average financing costs but also substantially increased the average life of its portfolio

The average cost of Spanish Treasury debt has fallen from 4.07% at the end of 2011 to current levels of 2.59%, supported by the decline in Spain’s risk premium and a sharp reduction in the risk-free rate. This improvement in average costs is a reflection of a decline in issuing costs, which have tumbled from 3.9% in 2011 to below 1% from 2015 onwards. And – absent a surprise interest rate shock – the average cost is likely to continue falling over the coming years with new financing costs remaining below the historical average.

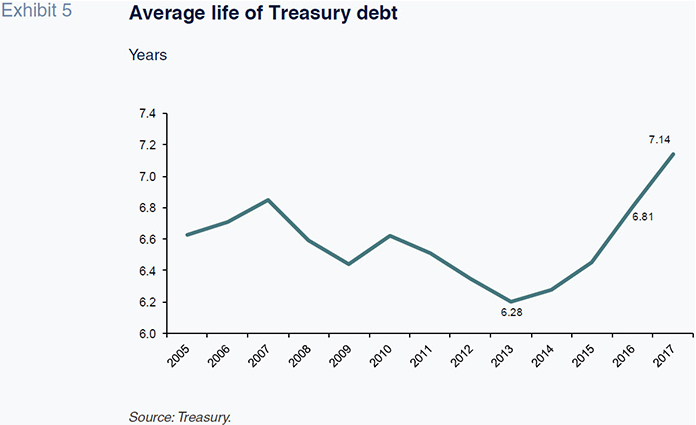

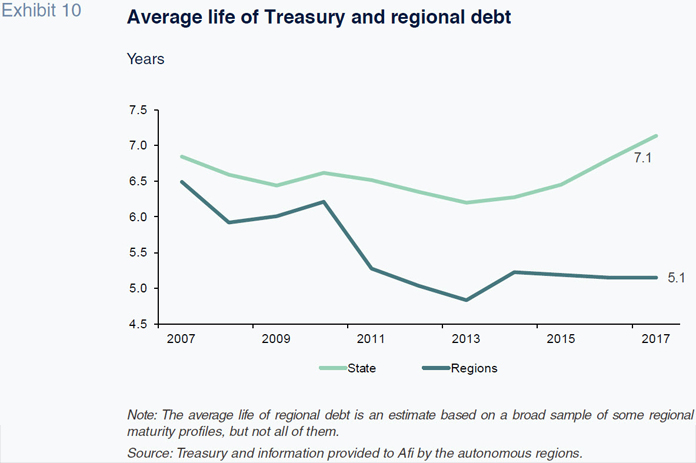

Furthermore, this reduction in average cost has been accompanied by a substantial increase in the average life of the portfolio, which has risen from 6.3 years at the end of 2013 to 7 years. This increase in average life has taken place across all European Treasuries, who have exploited the current low interest rate environment to lock-in extremely propitious financing costs over very long time horizons.

The average cost of sub-sovereign debt has fallen even more sharply than for the Treasury, especially in the case of the autonomous regions

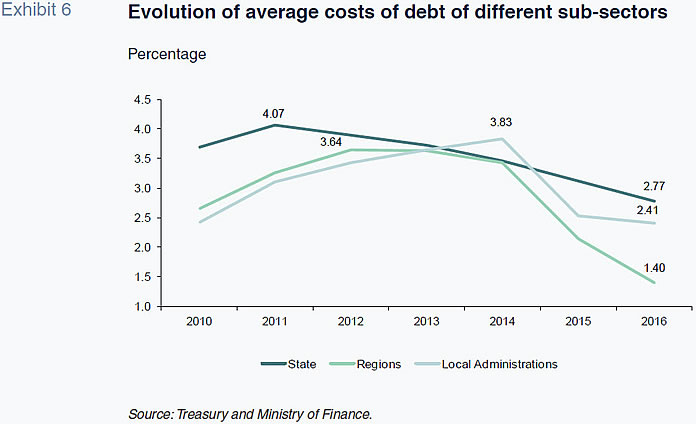

Funding costs for sub-sovereign administrations have also fallen substantially, reflecting the close link to Treasury financing costs. The average cost of debt owed by Spain’s autonomous regions

[1] fell from 3.64% in 2012 to 1.40% at the end of 2016, and from 3.83% in 2014 to 2.41% in 2016 for local administrations. While it is to be excepted that the general evolution of funding costs would be similar for both sub-sectors, the reduction in regional financing costs is particularly notable since autonomous regions are now funding themselves at nearly half the cost of the Treasury.

The main factors contributing to this drastic decline in regional financing costs – discussed in more detail below – are: the involvement by most autonomous regions in State financing mechanisms offering subsidised interest rates; the high proportion of loans in regional debt portfolios; and – to a lesser degree – the fact that, in general, the autonomous regions have not been able to take advantage of the current low interest rate environment to extend the average life of their portfolios.

Regional participation in State financing mechanisms does not in itself imply a reduction in the average cost of regional debt above and beyond the Treasury. In fact, this would not have been the case had the government decided to maintain its initial approach of applying a small spread on Treasury financing costs

[2]. However, in its July 2014 meeting, the Fiscal and Financial Policy Council opted for a different approach. The government announced a reduction in the interest rate to 1% for the regional liquidity mechanism

(Fondo de Liquidez Autonómico, FLA) from October 2014 until the end of 2015, which was below Treasury financing costs.

This decision initially appeared to be temporary and aimed at helping the autonomous regions comply with their fiscal targets in the face of challenges to consolidation (which were further accentuated by the failure to reform the Regional Financing System

[3] – a much needed reform that, three years, later remains outstanding). However, it ultimately became permanent and remains in effect today. Furthermore, the government decided in 2015 that all of the regional debt taken on with the State would bear an interest rate of 0% that year. And a new interest of 0.834% would apply to all outstanding regional debt with State financing mechanisms, substantially below previous rates. Given the already significant amount of regional debt channelled through state mechanisms, the latter measure translated into a very significant reduction in the interest burden, which continues to have an impact today.

Furthermore, a 0% interest rate was established in 2016 for autonomous regions which were compliant with their fiscal targets, who would be eligible for the Financial Facility

[4] compartment. Finally, this year the government has determined that all autonomous regions participating in the State mechanisms will finance themselves at a similar cost to the Treasury, regardless of their compartment

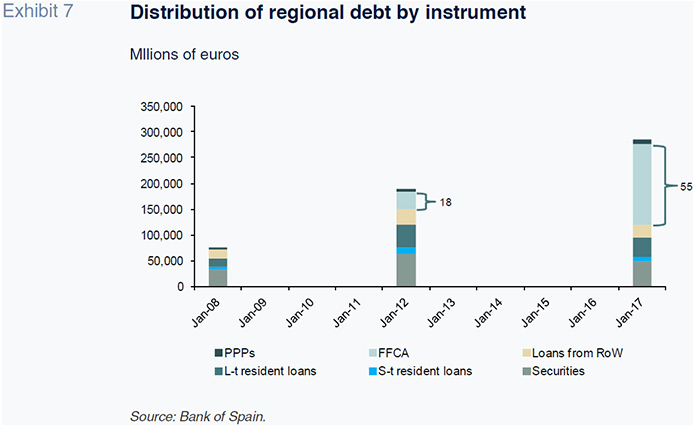

[5]. Overall, the series of support measures adopted by the government is the main factor explaining the major reduction in the average cost of regional debt. Especially considering that, as of the second-half of 2017, some 55% of all regional debt is now held by the Regional Financing Fund (FFCA).

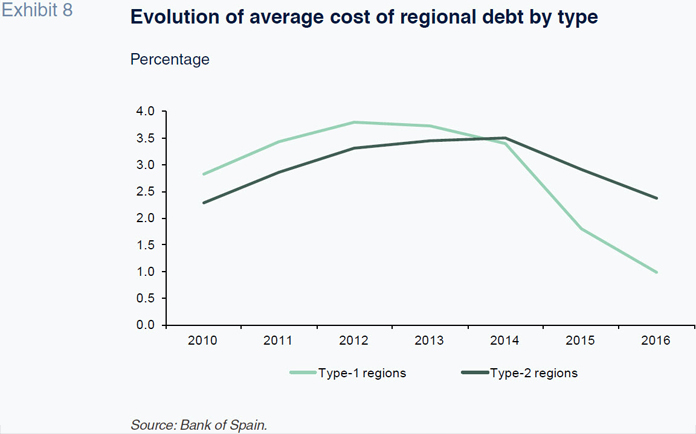

The impact of this policy approach can be seen when analysing developments in the average cost of debt of different autonomous regions. We have grouped the autonomous regions into two sub-groups: type-1 autonomous regions who owe over 65% of their debt to the FFCA

[6] and type-2 autonomous regions where the FFCA accounts for less than 50% of their total debt

[7]. Overall, type-2 autonomous regions have a better credit rating than type-1 autonomous regions, which is consistent with the lower average cost of funding enjoyed by the former until 2012. However, as shown in Exhibit 8, this trend has reversed dramatically and by the end of 2016, the average funding cost for type-1 autonomous regions was slightly below 1%, while the cost for type-2 autonomous regions reached 2.4%.

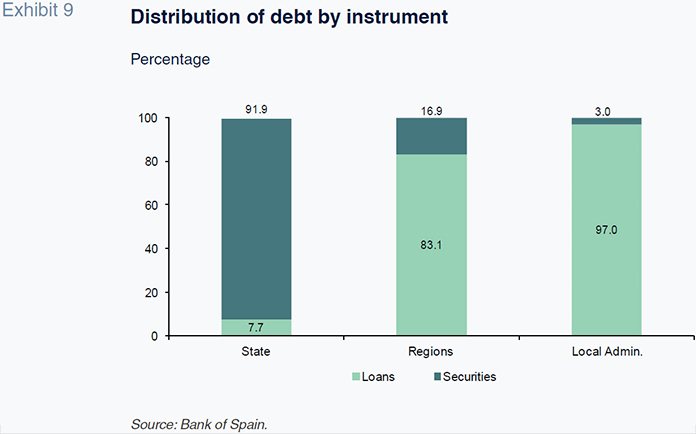

A lesser, albeit still very significant, factor in explaining the substantial reduction in average regional funding costs is the high proportion of loans in the regional debt portfolio. Following the sharp decline in credit spreads in recent years, this has enabled autonomous regions to refinance bank loans taken on at high interest rates – the majority of which were arranged in 2011 and 2012. By contrast, the bulk of the Treasury’s debt is in securities. This option is therefore not available to the Treasury with the only alternative being to exchange debt at market prices, which ultimately does not reduce the financial burden. As such, the Treasury is continuing to pay very high levels of interest on debt issued in 2011 and 2012 at a time when the risk premium was at a peak. This also explains why not only type-1 autonomous regions but also type-2 autonomous regions enjoy lower average funding costs than the Treasury.

In addition, although only residually important, the fact that the Treasury has sought to take advantage of low interest rates to lengthen the average life of its portfolio is also a factor in the interest rate differential relative to the autonomous regions. Indeed, most autonomous regions have not lengthened the life of their debt stock, which has remained stable over the last four years, at slightly over five years. This is essentially because the bulk of regional debt over recent years has been taken on via State funding mechanisms with a stipulated average life of 6.5 years, meaning that the average life of regional debt has not increased in contrast to most European public issuers.

Meanwhile, local administrations have also seen their average cost fall more sharply than the Treasury, which is essentially a reflection of the fact that nearly all of their debt is in loans. They too have been engaged in an intensive process of refinancing expensive debt. Furthermore, since the local administrations are the only level of the public sector to have deleveraged in recent years – debt has fallen from over 46 billion euros in June 2012 to around 32.5 billion euros in June 2017 – they have logically redeemed the most expensive debt.

Summary and conclusions

Perversely, the two autonomous regions with the lowest average cost of debt – Catalonia and Valencia – also have the worst credit ratings. Meanwhile, some of the autonomous regions with the best credit ratings are among those with the highest average funding costs. However, it is worth clarifying that the latter have taken advantage of the benign economic-financial backdrop to issue debt at very long maturities. This will lock in fixed rates at very favourable conditions and provide them with propitious financing costs for a long period of time. This is one of the strategic advantages which is not available to autonomous regions who recurred to the State. In the medium-term, autonomous regions who have relied on State mechanisms are therefore likely to be much more negatively affected by the normalisation of interest rates.

However, this is not to detract from the favourable impact of the State mechanisms, which have guaranteed the sustainability of many autonomous regions’ debt (albeit against a backdrop of a pressing need for a reform of the Regional Financing System, which remains pending). Furthermore, the State’s intervention has been beneficial for various stakeholders: for regional governments, who have been able to choose the best option in a benign financial environment; for investors, who have obtained both an implicit state guarantee against adverse scenarios while purchasing debt offering a spread against the Treasury; and for providers to the autonomous regions who continue to enjoy much shorter payment periods.

However, it is clear that part of the reduction in regional financing costs has been passed on to the Treasury, implying a transfer of risk from the regional level to the State. Logic would therefore suggest a gradual return to normality with autonomous regions resorting increasingly to market financing, subject to the fiscal discipline provided by market oversight, and reducing the risk of moral hazard.

Notes

The average cost for both the autonomous regions and local administrations has been estimated using budgetary execution data from the Ministry of Finance. The average annual interest cost is calculated as the coefficient of the financial expenses associated with obligations recognised in the spending budget and the average of the volume of debt in the year.

From its inception in 2012 until February 2014, the FLA applied a cost of Treasuries + 30bps. Thereafter from March-September 2014, the cost was Treasuries + 10bps. Meanwhile, the funding cost applicable in the first phase of the Payment Providers Fund was set at 3-month Euribor + 525bps, the equivalent of the Treasury´s funding costs + 142bps.

According to Ministry of Finance calculations, the Payment Providers Fund and the FFCA generated interest savings of 22.1 billion euros from 2012-16.

For those autonomous regions failing to meet their fiscal obligations and required to take part in the FLA (as opposed to the Financial Facility) the rate was equivalent to the Treasury´s funding cost.

The difference between the compartments lies in the fact that autonomous regions participating in the FLA are subject to additional fiscal conditions from the Ministry of Finance, which is not the case for autonomous regions in the Financial Facility compartment.

Type-1 autonomous regions: Andalusia, Castile-La Mancha, Canary Islands, Catalonia, Balearic Islands, Cantabria, Valencia and Murcia. In addition to having a high proportion of their debt with the FFCA, these regions also participated in the FLA each year since its inception and then subsequently in either of the two compartments of the FFCA – in contrast to type-2 autonomous regions.

Type-2 autonomous regions: Aragón, Asturias, Castile-Leon, Extremadura, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid, Navarre and the Basque Country. This group is more mixed. Some autonomous regions have over 30% of their debt with the FFCA, such as Aragon, Asturias, Extremadura and Galicia, while other autonomous regions have no debt whatsoever with the FFCA, such as Navarre and the Basque Country.

Salvador Jiménez and Carmen López. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.