2017-2018 autonomous regions’

economic forecasts and key challenges

The Spanish economy is expected to grow by 3.1% in 2017 and by 2.6% in 2018. The slowdown reflects a loss of impetus in domestic demand as well as political tensions in Catalonia.

Abstract: The Spanish economy is expected to register a growth of 3.1% in 2017 and 2.6% in 2018. The slowdown next year is related to the weakening in domestic demand together with the negative impact from the political tensions in Catalonia, which are expected to shave off 0.3 percentage points of national growth. Madrid, followed by Galicia and the Valencian Community are set to be the strongest performers. Meanwhile, Asturias, Catalonia and Extremadura are likely to be the slowest growing autonomous regions. The main factors explaining the differences in regional growth are: i) differing capacities to take advantage of the pick-up in world trade and the EU recovery, so as to compensate for the slowdown in domestic demand; ii) the overall state of play of public finances; and, iii) an investment diversion effect due to the Catalan situation. Going forward, the persistence of significant differences in unemployment performance across autonomous regions is one of the main challenges to territorial cohesion.

Recent economic performance by the autonomous regions

National GDP accelerated in the first two quarters of the year before slowing in the third quarter. Construction registered the strongest outturn, followed by services, although the loss of momentum in the latter was the main factor explaining the slowdown in growth in the third quarter. Madrid, the Canary Islands, Balearic Islands, Catalonia and Galicia were the fastest growing autonomous regions in the first three quarters of the year in comparison to the previous year. Construction and tourism were the main drivers of growth for the first three autonomous regions, while industry and exports played a more important role in Galicia and Catalonia.

Extremadura, Asturias, Castile-Leon and Murcia posted the slowest growth over the period due to a weak performance by either their industrial or construction sectors.

Spain’s overall exports grew robustly over the first eight months of the year, driven by foreign sales of oil products, capital goods and chemical products. This was particularly beneficial for autonomous regions where the oil products sector has a significant weight in their export structure (Canary Islands, Balearic Islands, Murcia and Andalusia), who registered the strongest growth in export sales over the period. However, not all the autonomous regions specialised in capital goods were able to take advantage of export momentum in this sector (notably Navarre and Cantabria whose capital goods exports were negative). Car exports fell slightly in the year to August, partly due to a decline in the UK market (which accounts for around 12% of car exports) and partly because of stoppages on some production lines as the result of introducing new models. Even so, three of the autonomous regions where the car sector is particularly significant – Aragón, Catalonia and the Basque Country – posted positive export revenue growth. Overall, not all exporting autonomous regions benefited equally from the good headline export performance, including some autonomous regions specialised in the fastest-growing sectors at a national level. Likewise, not all autonomous regions shared equally in tourism exports.

In terms of employment, social security registrations to October rose most in the Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Andalusia and the Valencian Community, with a notable increase in construction jobs in all these autonomous regions. Castile-Leon, Asturias and the Basque Country saw the slowest growth in social security registrations. However, Labour Force Survey data paints a somewhat different picture: on this measure Navarre, Castile-La Mancha, Andalusia and Asturias saw the strongest growth in the first three quarters, while employment growth was weakest in Extremadura, the Basque Country and the Balearic Islands.

2017-18 forecasts

The Spanish economy is forecast to grow by 3.1% in 2017 and 2.6% in 2018, although the latter is subject to significant uncertainty stemming from the difficulties associated with quantifying the impact of the political tensions associated with developments in Catalonia. The instability brought about by this situation has negative implications for the economy – primarily the Catalan economy –

through temporary or more longer-lasting retrenchment in consumption, investment and hiring intentions. The situation could also affect economic activity through a slowdown in lending because of an increase in risk perceptions.

These forecasts are based on a scenario which assumes that the situation in Catalonia normalises from the second quarter of next year onwards. Under this assumption, growth in the Catalan economy will slow significantly but only for a short period with little effect on the other autonomous regions. The Catalan economy could expand at around half the initial rate of growth forecasted for the next six months, recovering thereafter. Accordingly, annual growth in Catalonia could slow 3.1% in 2017 to 1.7% in 2018, shaving 0.3 percentage points off national growth.

Alongside political tensions, a loss of impetus in domestic demand is likely to undermine growth by another 0.2 percentage points, as some of the factors driving growth in previous years begin to fade.

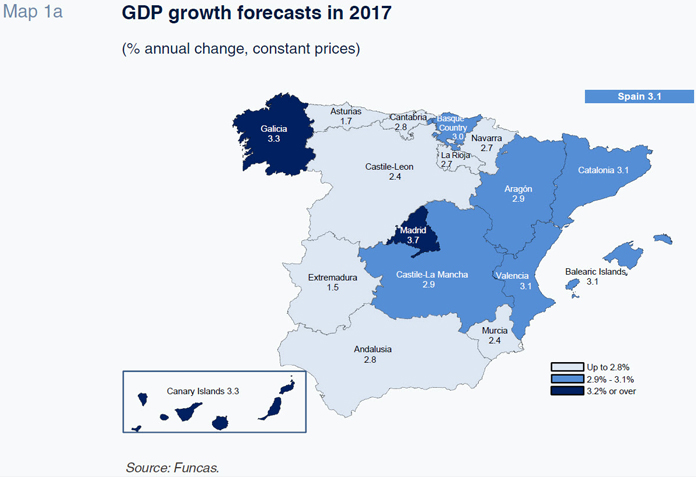

Madrid, the Canary Islands and Galicia are set to post the strongest growth this year, with Extremadura, Asturias, Murcia and Castile- Leon the main laggards. Given the backdrop of a slowdown in overall Spanish economic growth, it is worth highlighting the pick-up in activity in La Rioja, followed by Cantabria, though from very modest growth rates in both autonomous regions in 2016. By contrast, Castile-Leon has slowed the most notably this year (Map 1a).

Turning to 2018, the outlook for nearly all autonomous regions is likely to reflect the general easing of growth expected at the national level. Madrid, followed by Galicia and the Valencian Community are set to be the strongest performers. Growth in Madrid will be fuelled by services, while industry will provide impetus to growth in the other two autonomous regions buoyed by both domestic demand and exports. Meanwhile, Asturias, Catalonia and Extremadura are likely to be the slowest growing autonomous regions. Leaving to one side Catalonia’s individual circumstances, the growth capacity of the other two autonomous regions remains hampered by structural factors. Tourism is likely to play a less significant role in driving growth than in 2017 (Map 1b).

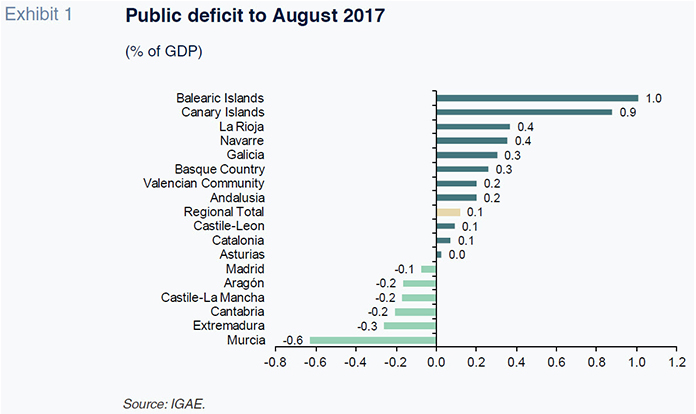

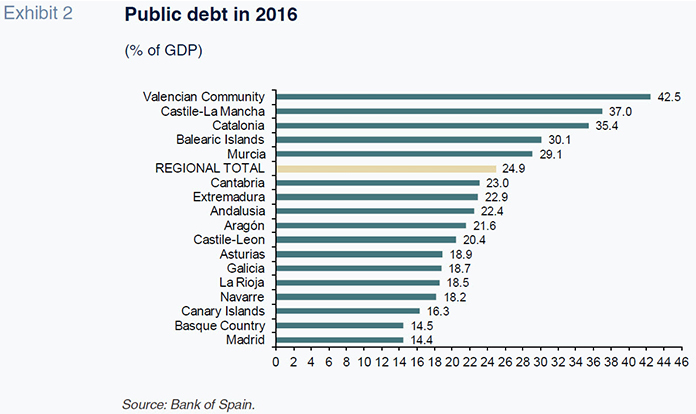

The main factors explaining the differences in regional growth are: i) autonomous regions’ differing capacities to take advantage of the pick-up in world trade growth and the European recovery, and their ability to compensate for the slowdown in domestic demand (which favours autonomous regions in the Ebro valley, Galicia and Madrid); ii) the overall state of play of public finances, which remains an impediment for some autonomous regions such as Murcia (Exhibits 1 and 2); and, iii) an investment diversion effect due to the Catalan crisis, to the benefit of neighbouring autonomous regions – especially Aragón and the Valencian Community – as well as Madrid (to a lesser degree).

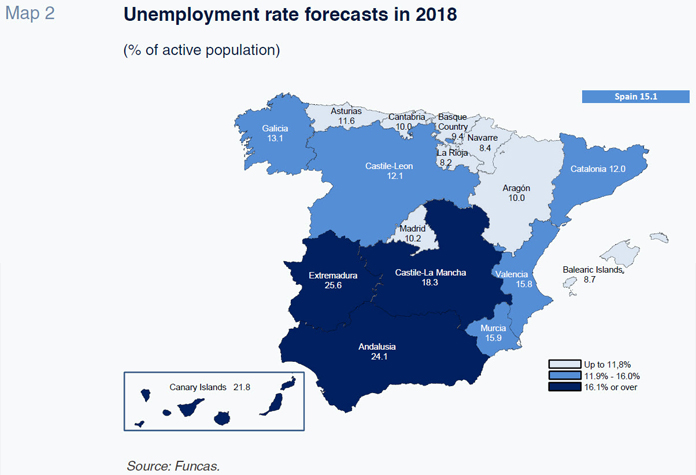

Main challengesThe persistent significant differences in unemployment performance across autonomous regions is one of the main challenges to territorial cohesion. Four autonomous regions will see unemployment drop below 10% in 2018 (the Balearic Islands, Navarre, Basque Country and La Rioja). In the not too distant future, these autonomous regions could find themselves facing labour shortages in certain sectors (Map 2).

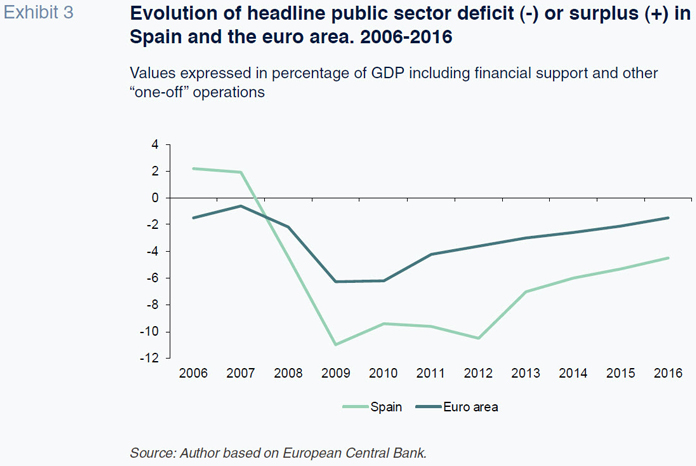

By contrast, unemployment remains above 20% in three autonomous regions (Andalusia, Canary Islands and Extremadura). Addressing these significant imbalances requires new investments which generate employment, as well as closing the significant gaps in education levels (Exhibit 3). Initiatives aimed at overhauling the production system, such as those seen in Malaga (one of the provinces which has seen the largest decline in unemployment over the last year) underline the effectiveness of these types of strategies.

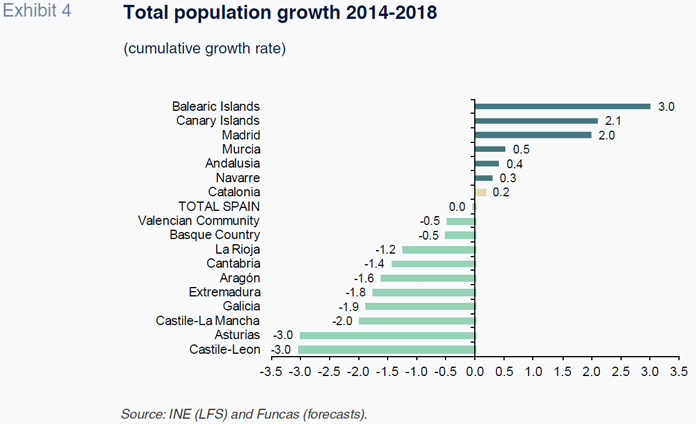

Meanwhile, some autonomous regions face adverse population dynamics, which will weigh on economic growth perspectives if not reversed in the medium-term. Significant inner areas of the Iberian Peninsula, as well as Asturias and Cantabria, among others, are losing population. Meanwhile, Madrid and the Mediterranean autonomous regions are seeing an increase in the number of inhabitants (Exhibit 4).

Strengthening development hubs in rural environments will undoubtedly help to slow this demographic crisis. Internal areas of Catalonia, the two Castiles and Galicia have also enjoyed some success in stemming population outflows by improving connections with more dynamic populations such as Barcelona, Madrid and the Galician coast.

Finally, should the independence tensions fail to dissipate, the country’s economic geography could be significantly rewritten, as illustrated by Quebec in Canada. Repeated independence consultations in this Canadian region have led to a gradual diversion of investment towards other parts of Canada, leading to a deterioration in per capita incomes and employment in Quebec.

Notes

María Jesús Fernández and Raymond Torres. Economic Perspectives and International Economy Division, Funcas