Tensions in the U.S. and eurozone sovereign debt markets

Transatlantic divergence in fiscal and monetary policies is driving renewed volatility in sovereign bond markets, with U.S. Treasury yields elevated and eurozone spreads widening, particularly in Germany. Going forward, the lack of economic policy coordination could continue to generate episodes of instability in international financial markets.

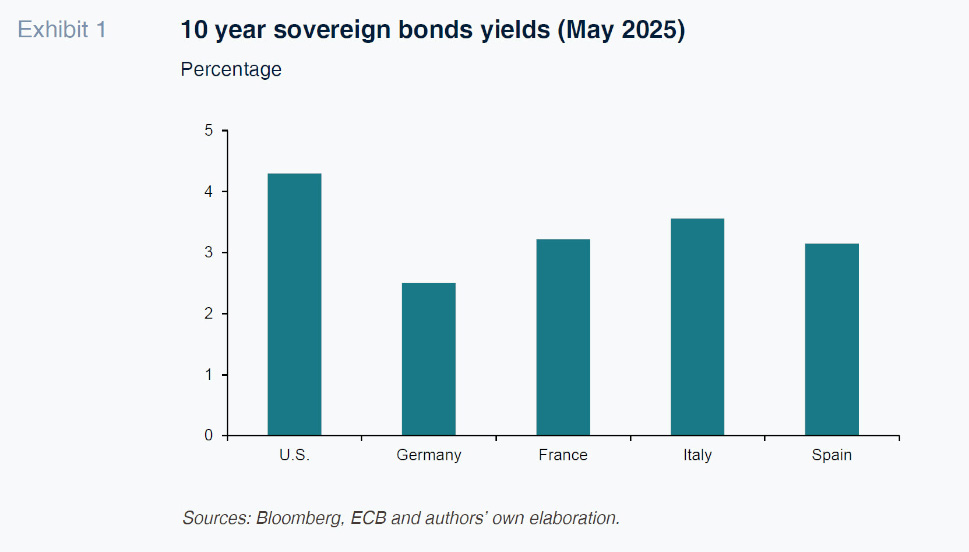

Abstract: Transatlantic divergence on fiscal and monetary policies have underpinned recent tensions in both the U.S. and eurozone sovereign debt markets. In addition to exhibiting high volatility, in May 2025, 10-year U.S. Treasury yields remained above 4.3%, driven by a high fiscal deficit and rising public debt, accentuated by an exodus by traditional institutional investors and higher activity by price-sensitive players. In the eurozone, the expansionary shift in German fiscal policy —particularly the €100 billion increase in defence spending— has pushed Bund yields to around 2.5% while peripheral country risk premiums had risen somewhat: the Italian risk premium stood at over 100 basis points and the Spanish spread stood at around 65bps. Meanwhile, the ECB has lowered its deposit rate to 2.25%, following six consecutive cuts since mid-2024, and faces the challenge of supporting growth without importing inflation. This combination of factors initially reinforced capital flows to the U.S., strengthening the dollar and increasing global financial fragmentation, but tariffs and uncertainty have ultimately reversed these capital flows and weakened the dollar. Going forward, the lack of economic policy coordination could continue to generate episodes of instability in international financial markets.

Foreword

The combination of recent political decisions and unexpected volatility has sparked tension in the bond markets in the U.S. and Europe alike. In the U.S., Treasury yields have increased sharply, fuelled by a high public deficit and adjustments in global demand for American public debt. According to the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report from April 2025 [1], global financial stability risks have increased significantly, driven by tighter global financial conditions. This pressure intensified sharply after Trump announced his tariffs in April, sparking considerable volatility in the debt markets. The term premium has spiked, which means that investors are demanding a higher return on sovereign bonds in the U.S. and eurozone (Exhibit 1), fuelling the risk of sudden price corrections.

In tandem, in the eurozone the shift in German fiscal policy, including a historical increase in military spending, has pushed yields on German Bunds higher, while the ECB has remained in monetary easing mode. The divergence between fiscal and monetary policy in the two regions had initially driven an increase in the yield gap and attracted capital flows to the U.S., strengthening the dollar and pressuring global financial stability. In recent weeks, however, the uncertainty ushered in by the new Trump administration has affected those capital flows (drawing a certain amount back to the eurozone) and the value of the dollar. There has even been speculation that the Federal Reserve could be forced to intervene to stabilise the bond markets if tensions persist.

Some analysts have pointed out that the current high yields on bonds are partly the result of changes in fund flows: traditional demand from price-insensitive investors (foreign governments, the Fed, life insurers) has fallen back, with more price-sensitive players (hedge funds, ETFs) coming into play. Some of these buyers, like the hedge funds, are highly leveraged. This shift in debt holders is amplifying volatility. In fact, the term premium in the U.S. has shot up to its highest level since 2014, reflecting that investors are demanding growing compensation for duration risk. In these conditions, the main Treasury bond dealers are facing a supply surplus without sufficient automatic buyers, putting upward pressure on rates.

In short, the sharp increase in Treasury yields has been driven by both fiscal expansion and technical market dynamics. What has happened is already being termed an exodus (probably temporary and/or partial) from longer-term Treasury bonds that has already implied a major global unwinding of positions in supposedly safe assets. This paper takes a look at these discrepancies between the U.S. and eurozone, emphasising their implications for the financial markets, financial stability and economic growth.

Sources of uncertainty in the debt markets

Uncertainty around trade and the step change in German fiscal policy has triggered the largest exodus from American and European bonds since at least 2020. Many managers believe that the leveraged funds have exacerbated market volatility. The resulting high yields are increasing government borrowing costs (as noted by Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who is insisting on avoiding excessively high yields) and testing the Fed’s ability to contain a wave of forced sales without overwhelming the financial markets.

In Europe, the headline is the shift in German fiscal policy. The coalition government approved an ambitious spending plan, including around 100 billion euros of additional defence spending this year (the biggest post-war increase in military spending) and billion-euro packages for infrastructure, the green transition and digitalisation. This fiscal impetus, enabled by relaxation of the debt brake written into the constitution, took the markets by surprise. In the week of the announced coalition agreement, the yield on 10-year Bunds shot up around 50 basis points, wiping out several weeks of decreases. The market had already priced in higher future spending but the scale of the increase drove a sharp spike in Germany bond yields. In fact, between September and March, the risk premium between the Bund and the European 6-month swap widened by 43bps, indicating expectations for higher inflation in Germany. This phenomenon has several explanations. The prospect of higher inflation could complicate the ECB’s mandate: even though core inflation in the eurozone has fallen back towards 2.2% and the ECB has continued to cut rates, which stood at 2.25% by April (after six straight reductions), the sudden increase in public spending adds inflationary pressure.

Some analysts are warning that German defence spending (and in European defence spending in general) could import inflation into the eurozone. It could boost internal demand but it could also fuel energy and raw material costs. Against this backdrop, the ECB is facing contradictory tensions. It wants to continue to revive the economy (protracted subdued growth) by keeping rates low, but it does not want the new fiscal measures to import inflation from abroad in the absence of sufficient internal demand to justify it. The ECB is not ruling out additional rate cuts but doubts linger as to whether this strategy can reactivate the economy without generating imported inflation. In fact, the ECB has raised its forecast for inflation in 2025 (to 2.3%) precisely because of stronger energy price dynamics and other external price pressures. This has sparked internal debate about pausing rate cuts or ending the rate-cutting cycle sooner than anticipated.

Meanwhile, German fiscal policy has impacted the bonds of other eurozone issuers. Core European bonds have also seen their yields trade higher, while the peripheral issuers have experienced spread tightening in some cases (for example, after the credit rating agencies reaffirmed their sovereign bond ratings). However, the bonds issued by governments with more debt remain somewhat volatile. For example, in the days following the announcement of U.S. tariffs, the Italian risk premium rose to around 130 basis points (with its 10-year bond trading at around 3.97%).

In Spain, the spread over the German Bund remains at around 65 basis points (data as of May). The experts warn that persistent economic weakness in Europe and institutional fragmentation (as seen in the staggered yet unstable return of the fiscal rules and emphasis on consolidation) could once again take centre stage, exerting fresh pressure on risk premiums. Indeed, the OECD has trimmed its forecasts and is currently estimating scant growth of 1% in the eurozone in 2025 (down from 1.3% in December), with the German economy expected to grow by just 0.4%. This low-growth environment limits the space for alleviating debt via growth, which is why investors are demanding a relatively high risk premium in the more indebted countries. In short, the clash between higher public spending in Germany and a sluggish eurozone economy has caused tensions in the European debt markets. Analysts stress that without a sharp increase in growth, Germany will lose the advantage it had previously commanded (robust and countercyclical). Meanwhile, the ECB insists that the deflationary process remains ongoing but that the effects of rearmament on future inflation and perceived European debt risk need to be watched closely.

Policy divergence and global repercussions

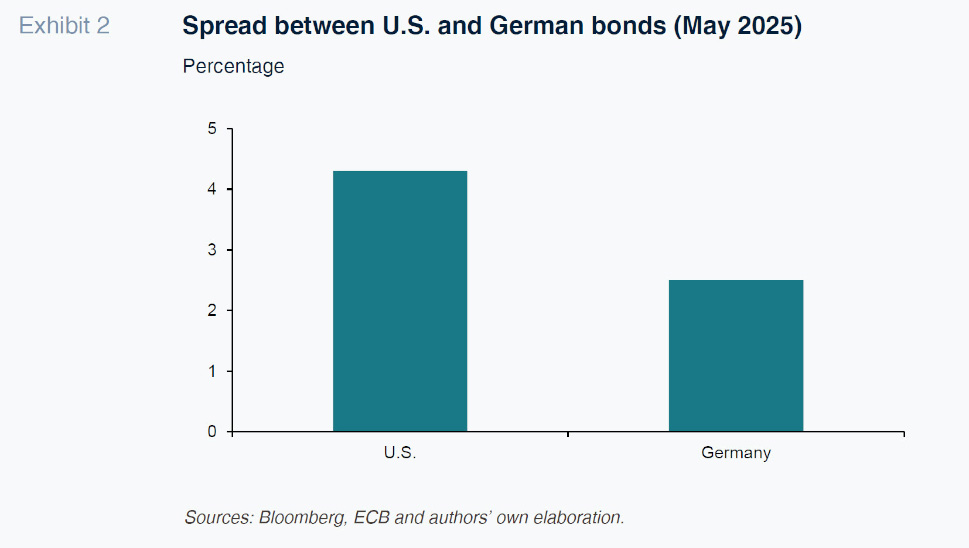

The mix of monetary (Fed on pause vs. ECB in rate-cutting mode) and fiscal policies (expansionary in the U.S. and moderate in Europe with the odd exception) has heightened the economic divergence between the two regions. As a result, the spread between the two regions’ bond yields has widened (Exhibit 2).

This divergence contributed to dollar appreciation six months ago. The higher yield on U.S. bonds drew global capital into dollar-denominated assets, to the detriment of other regions. These flows in turn pushed up financing costs in the eurozone (adverse exchange rate) and increased the global risk premium. However, this trend has shifted in recent months, as tariff announcements and the lack of hard data about the long-term fiscal direction in the U.S. have hurt the value of the dollar, despite the interest rate differential between the U.S. and eurozone. Moreover, the prospect of divergent policies heightens volatility: the markets are currently discounting more rate cuts in Europe than in the U.S. (specifically, an additional 75 basis points by the ECB in 2025 vs. 50bps by the Fed, which has yet to lower its rates this year).

In terms of global financial stability, the issue resides with the fact that U.S. debt, long seen as a safe haven, is currently paying significantly higher rates than nearly all of the major advanced economies. As a result, the Treasury’s immunity to potential crises has come under scrutiny. At the same time, geopolitical uncertainty and protectionism are increasing international volatility. In sum, geopolitical fragmentation and protectionism are exacerbating economic uncertainty, generating volatility in the bond marks and a lack of global policy coordination.

The IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report from April 2025 warns that high sovereign indebtedness, in both advanced and emerging economies, could unleash episodes of instability in the bond markets, especially if the highly leveraged non-bank funds (part of the so-called shadow banking system) are forced to unwind positions. This vulnerability has been aggravated by the growing nexus between banks and investment funds, amplifying the transmission of shocks. It is important to ensure the availability of liquidity mechanisms to contain episodes of stress, particularly in the more vulnerable sovereign markets. The IMF also recommends improving the quality and granularity of the data on non-bank financial institutions to enable a more accurate assessment of the systemic risk.

In practice, the agents are adjusting their portfolios. The eurozone’s varying internal indicators once again signal the risk of fragmentation: in an environment of weak growth, heterogeneous fiscal governance could lead to sudden stress in peripheral country risk premiums. In short, the current tensions in the sovereign debt markets reflect a clash between very different contexts. In the U.S., the enormous fiscal deficit and a bond market increasingly reliant on price-sensitive investors (leveraged funds) are pushing long-term rates higher. In Europe, the radical shift in German fiscal policy has altered inflation expectations and perceived risk around the Bund, at a time when the eurozone economy continues to need monetary stimulus.

This decoupling is generating contrasting interpretations and predictions. On the one hand, considering only the theoretical effect of the rate differential, the natural conclusion would be that the current situation will reinforce flows to the U.S. and widen spreads, increasing global financial fragmentation. Investors are following these dynamics closely, with Wall Street strategists cautioning that if global policy does not normalise, the markets could continue to react abruptly to any unexpected news. Another interpretation, however, is that the political and economic uncertainty prevailing in the U.S., particularly since the imposition of tariffs by the Trump administration, has caused international investors to worry. According to the IMF, this uncertainty has prompted a reassessment of global demand for dollar-denominated assets, hurting investor confidence. Moreover, dollar depreciation and financial market volatility have eroded foreign investments in the U.S. In contrast, Europe may be becoming more attractive as a destination for investment.

In sum, although the U.S. had been registering strong inflows of capital until the early part of this year, growing uncertainty and improved prospects in other regions suggest that these flows may not be sustainable in the long term and that investors may be diversifying their portfolios into markets with more solid and predictable fundamentals.

Conclusions

The recent tensions in the sovereign bond markets illustrate the extent to which fiscal and monetary policy coordination is crucial to avoiding episodes of financial instability. The interplay between persistent deficits, expansionary fiscal agendas and shifts in the composition of sovereign bond holders is generating a new balance of risks, less anchored in the traditional notion of safe haven assets. As global investors fine-tune their portfolios, not only in response to relative rates but also perceived macroeconomic governance, the markets are becoming increasingly sensitive to any sign of dysfunction.

Geopolitical fragmentation is further complicating this complex environment, reinforcing centrifugal dynamics in the eurozone and also in the international financial system. Uncertainty about where U.S. fiscal policy may be headed, the reconfiguration of strategic priorities in Europe and significant exposure to non-bank funds warrant a more integrated approach to economic policy. Stabilising rates or adjusting spreads will not suffice: it is essential to reinforce the institutional mechanisms for reducing systemic risk in the event of global shocks. The current turbulence could be a taste of what might lie in store if progress is not made towards more coherent governance.

Notes

Santiago Carbó Valverde. University of Valencia and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas