Spanish fiscal policy in the face of systematic budget rollover: Risks for stability and reform

Despite robust growth and a declining headline deficit in 2024, Spain’s underlying fiscal trajectory remains fragile due to persistent structural imbalances and high public debt levels. With the new EU fiscal framework taking effect and long-term spending pressures building, credible consolidation measures are becoming increasingly necessary.

Abstract: Spain’s fiscal performance in 2024 benefited from strong economic growth and buoyant revenues, helping to reduce the headline deficit to 2.8% of GDP. However, this improvement largely reflected cyclical dynamics, with the structural deficit decreasing only slightly to remain above 3%. Budget planning for 2025 has been clouded by political uncertainty, resulting in a sharp divergence in medium-term consolidation scenarios between the government and independent institutions. At the subcentral level, regional governments posted near-balanced budgets thanks to sharp growth in tax collections and the national strategy of sheltering them during the pandemic years, while local governments registered a surplus, supported by relatively flat spending. Looking ahead, demographic change, climate-related spending, defence requirements, and external shocks are expected to add further strain. In this context, fiscal sustainability will depend on rebuilding consensus, strengthening institutions, and adapting Spain’s budgetary framework to emerging risks and long-term demands.

Foreword

Spain’s budget dynamics in 2024 had highlights and lowlights. The trend in the deficit, as calculated for fiscal rule application purposes, was clearly positive. Expressed as a percentage of GDP, it came down by over 0.7 points from 2023 (Ministry of Finance, 2025). The spending rule was missed, however. Compared to the targeted growth of 2.6% in 2024, AIReF (2004) estimates overall growth of 4.1%.

Putting the above numbers into context helps understand both outcomes. Firstly, Spain’s economic performance was exceptional, particularly in comparison with the EU-27. GDP growth was intense (+3.2%), fuelling tax receipts and social security contributions. While nominal GDP grew by 6.2%, tax revenue jumped 7.7%, and contributions increased by 6.7%. Secondly, although 2024 was governed by a general state budget carried over from the previous year, spending dynamics were expansionary. Momentum in spending coupled with new executive decrees led to growth in non-financial spending of 6.2%.

Until recently, the outlook for 2025 was looking very similar. The probability that the 2023 general state budget would be carried over once again was increasing as the weeks went by and the economy remained dynamic. However, Donald Trump’s return to the White House has triggered an intense systemic shock that has turned everything on its head, to an extent that cannot yet be gauged. His announcements and decisions around tariffs have undermined expectations and are bound to slow Spanish economic growth in the second half. Moreover, his demand that NATO member states significantly and quickly step up their defence spending will exert further pressure on expenditure.

Looking to the medium term, the projections are shaped by the new European fiscal rules, the need to invest in the energy transition and climate action, the budgetary requirements emanating from the Competitiveness Compass that end up falling to the EU-27 member states to finance, and the end of the NGEU funds in 2026. In sum, a challenging horizon that is scantly compatible with a no-change approach to budgeting.

Results for 2024

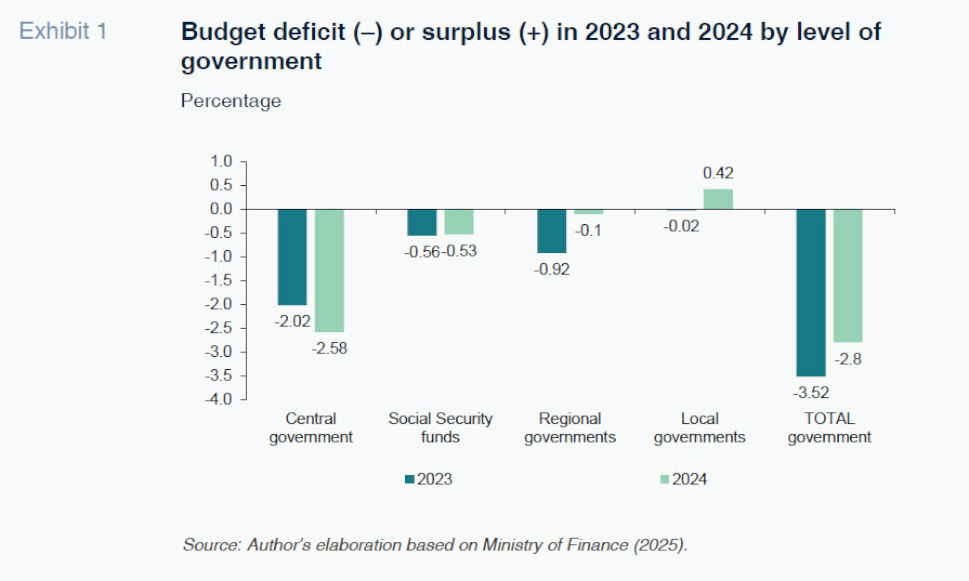

Spain’s public deficit reached 2.8% of GDP in 2024, excluding the one-off impact of the flash flooding that devastated the region of Valencia in November, a shock estimated at 5.59 billion euros, equivalent to 0.35% of GDP (Exhibit 1). Leaving aside that outlay, between 2023 and 2024, the ratio of spending to GDP came down from 45.45% to 45.06% (-0.39pp), total non-financial revenue increased from 41.93% of GDP to 42.26% (+0.33pp), and the tax-to-GDP ratio increased by 0.5pp: from 37.2% to 37.7%. Eurostat has already confirmed these figures. [1]

The 0.72 percentage point reduction in the deficit relative to GDP is the direct result of an improvement at the subcentral government level, as the Social Security’s deficit is stagnant and the state deficit increased by more than half a point last year (0.56pp). Sizeable payments to the regional governments under the regional financing system corresponding to 2022 (paid in 2024) are responsible for both the improvement at the subcentral level and the deterioration in the state deficit. That settlement increased by 13.52 billion from 2021, around 0.9 percentage points of GDP (Ministry of Finance, 2025). The fact that the local governments have returned to surplus territory is also related to larger transfers from the central government.

In short, the changes in the internal composition of the overall deficit have been shaped primarily by intergovernmental transfers, rather than by differing efforts to control spending dynamics. According to the preliminary figures released by AIReF (2024), net primary expenditure decreased at the central government level in 2024 (-2.9%), compared to an increase of 7.0% at the regional government level.

The assessment is richer and more nuanced if we look at the estimated structural component of the overall deficit. According to the calculations included by the Spanish government in the Medium-Term Fiscal-Structural Plan 2025-2028 sent to the European Commission in October of last year (Government of Spain, 2024), the structural deficit decreased by just 0.2pp, from 3.3% to 3.1%, between 2023 and 2024. Therefore, even considering the fact that the overall deficit came in at 2.8%, rather than the 3.0% estimated by the government itself in that plan, over half of the improvement is attributable to the cyclical component of the deficit, i.e., to favourable economic momentum.

Forecasts for 2025

The government’s forecasts for 2025 call for a deficit of 2.5% and compliance with the ceiling of 3.2% on growth in eligible public spending. Assuming no policy changes, AIReF (2024) is forecasting a deficit of 2.7% and growth in spending of 3.7%. In both cases, the independent fiscal institution is forecasting slight deviations. Certainly, the failure to present and pass a new budget is generating uncertainty about what might ultimately happen and making it extremely difficult to make forecasts.

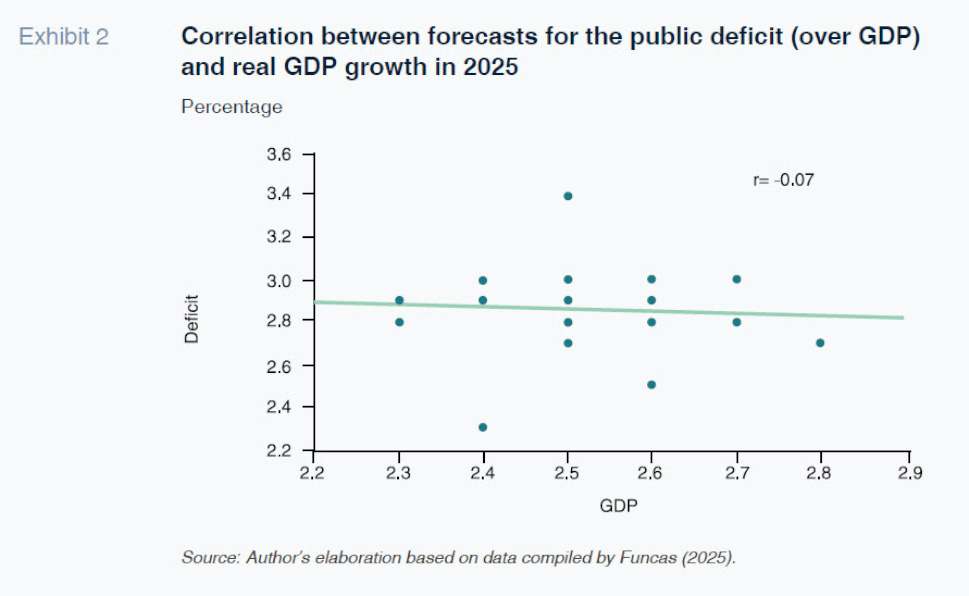

The Funcas consensus forecast as of May 2025 sums this situation up. Exhibit 2 illustrates the combined forecasts for the deficit and GDP growth of 23 public and private institutions and the corresponding regression line and linear correlation coefficient.

[2] The range of deficit forecasts is wider than the range of GDP forecasts. The estimates for the former range from 2.3% to 3.4%, compared to a range of 2.3% to 2.8% for the latter, with averages of 2.9% and 2.5%, respectively. More remarkable still is the total absence of correlation between the growth and deficit forecasts: the analysts who expect the economy to post stronger growth do not have faith in a bigger deficit reduction. The reality is that it is becoming harder than ever to forecast, and monthly oversight is becoming vital.

Medium-term horizon

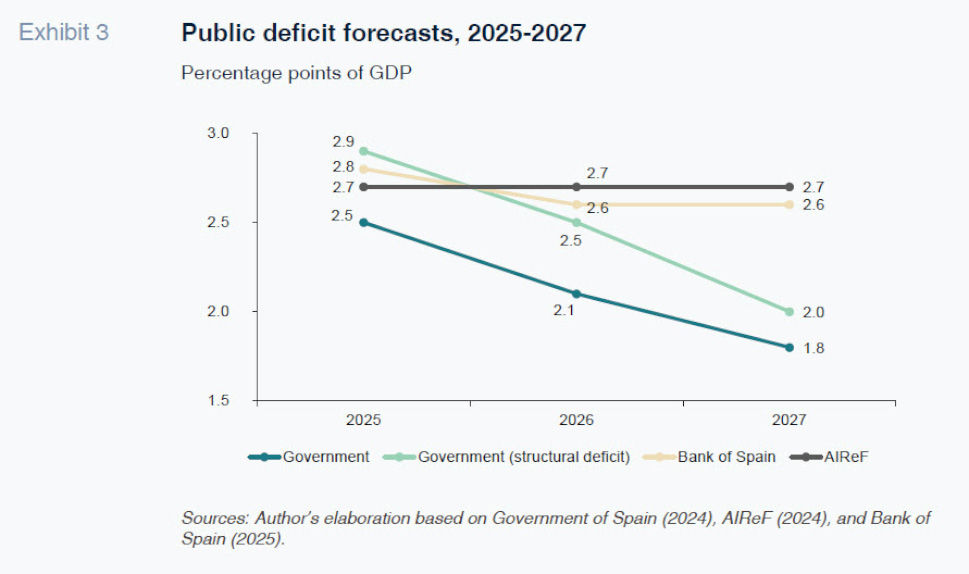

Exhibit 3 depicts the fiscal consolidation pathways estimated for 2025-2027 by the government, the Bank of Spain, and the AIReF. It also layers in the trend in the structural deficit (net of the impact of the economic environment) forecasted by the government.

In 2025, the government is looking for a bigger reduction. However, considering that in 2024 the deficit came in 0.2 percentage points below the government’s and both institutions’ estimates, the three sets of forecasts for fiscal consolidation in 2025 are essentially compatible. The difference is more pronounced in the following years. The government is forecasting a substantial and sustained reduction in the overall deficit, enabled by a proportionate improvement in both the structural and cyclical components. In contrast, the Bank of Spain and AIReF believe that, assuming a no policy-change scenario, consolidation will stagnate, with the deficit getting stuck at closer to 3% than 2.5%.

Compliance with the EU fiscal rules will oblige tighter control over growth in eligible expenditure net of discretionary revenue measures, which is why the government is forecasting an annual reduction in the structural deficit of close to half a percentage point. The government’s deficit reduction path would pave the way for accelerating the reduction in the ratio of public debt to GDP and give it a certain amount of fiscal margin of manoeuvre for tackling unexpected shocks. In other words, the targets are reasonable and already aligned with what the EU expects from Spain. What is missing are the specifics as to how the targets will be attained and how the government will move from the scenario of no policy-change to one of proactive budget consolidation.

What is happening at the subcentral government level?

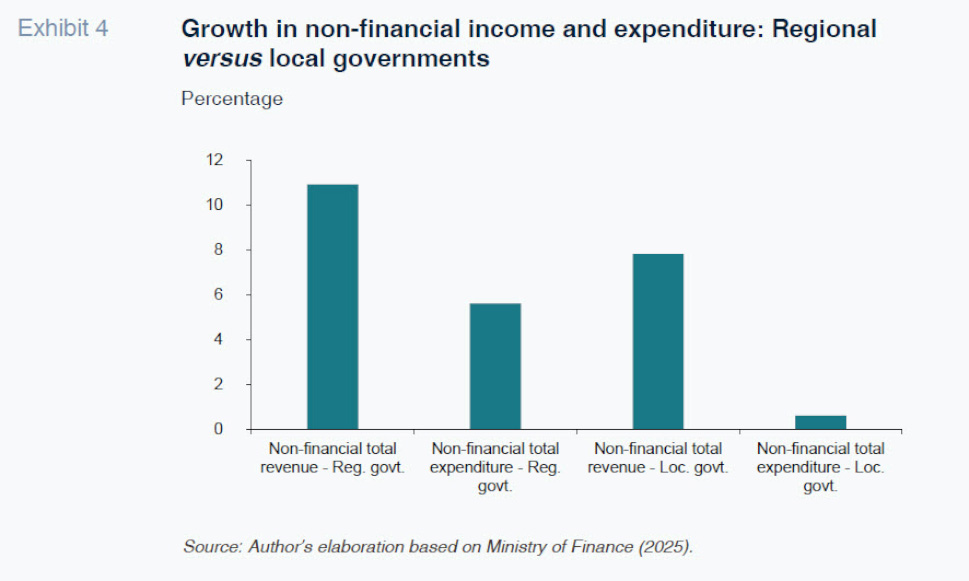

The budget settlements in 2024 (Ministry of Finance, 2025) depict an asymmetric financial scenario at the regional versus the local subcentral government levels (Exhibit 4).

Starting with the regional governments, non-financial revenue increased by 10.9%, nearly four points above the total blended figure. The first explanation lies with how the common-regime regional governments’ financing system works. The grants are settled with a two-year lag, which ends up generating unanticipated and often destabilising financial effects. This revenue growth allowed the regional governments to reduce their deficit by 0.8 points of GDP to end the year with an almost balanced budget (-0.12% of GDP), despite substantial growth in spending: +5.6%. The AIReF’s calculations estimate even higher growth in the non-primary expenditure included for spending rule purposes, implying growth of more than double the ceiling rate.

There are several takeaways from the developments of 2024. Firstly, the regional governments as a whole are not facing a funding shortage, thanks to sharp growth in tax receipts over the past three years and the strategy of sheltering them during the pandemic years. Regional financing reform remains necessary and pressing, but for different reasons (Cadaval et al., 2024). Secondly, greater importance needs to be attached to the spending rule in the new fiscal rule framework, and, by extension, the public debate. Reducing the deficit is not good enough if the consolidation is the result of extraordinary and automatic growth in revenue. Lastly, it is urgent to recalibrate the fiscal stability framework at the subcentral government level. Specifically, in situations such as 2024, compliance with the spending rule should and would have generated a budget surplus for financing a rainy-day fund. Most of the regional spending relates to essential services (health, education and social services) that are hard to cut during adverse economic times. The idea behind a rainy-day fund is to be able to absorb variations around defined average medium-term growth in spending.

The reality facing the local governments is different. Their non-financial income increased only slightly above the aggregate government average (+7.8%), but their spending was flat (+0.6%), allowing them to move from a balanced budget to a surplus of 0.4 percentage points. The local governments continue to offset the figures corresponding to the rest of the subsectors.

A few thoughts about long-term fiscal risks

It is hard not to get bogged down by current affairs. However, we must not lose sight of the fact that budgeting is also conditioned by long-term trends, the emergence of new demands for intervention, and the stark fact that the frequency and intensity of extreme events with negative fiscal consequences are on the rise.

Long term, climate change and population ageing will put pressure on the public finances, whereas digitalisation presents a window of opportunity for using funds more efficiently.

[3] We have good insight into how demographic trends affect spending, but we know less about how they will affect tax revenue. Climate change, meanwhile, is an area in which estimates are still very imprecise. Moreover, there is uncertainty around the role the EU will play in financing the investments needed to anticipate the effects of climate change or accelerate the energy transition.

As for new demands, defence spending springs to mind. Spain has been spending very little by comparison with other countries, and the new paradigm is going to oblige it to make a bigger effort to catch-up over the rest of the decade.

Lastly, the extreme events include financial crises, pandemics, climate events, and fires. A recent AIReF (2025) report on fiscal risks provides good reading material in this respect. The key implication of events such as these for budgetary practice is that we need to reinforce response mechanisms. Use of the Contingency Fund should be limited to financing truly unforeseen, non-discretionary spending commitments, and the overall contribution to it should be scaled up to reflect the expected magnitude of these fiscal risks. However, the experience of the last 15 years tells us that the size of certain shocks would require setting aside excessive volumes of contingency funds that would not be necessary most years.

Without question, the so-called Solidarity and Emergency Aid Reserve (SEAR), created in 2021 by bringing together two pre-existing mechanisms (the Emergency Aid Reserve for technical assistance and the European Union Solidarity Fund (EUSF) for financial assistance) is a valuable and intelligent collective insurance mechanism for addressing natural disasters or public health emergencies. However, its financial capacity will surely have to be increased going forward. There is one more very important reason for fiscal prudence and stability. It is time to drive a very simple idea home: a state’s capacity to respond fiscally to an extreme event is much greater if its public debt ratio is 60% rather than 100%. That is why it is essential to use good economic times not interrupted by extreme events to bring about rapid reductions in that ratio.

Notes

The forecast pairs coincide in six cases, which is why the scatter chart only has 17 points.

Refer to the recent edition of Papeles de Economía Española on “Retos pendientes del sector público español” [Outstanding challenges in the Spanish public sector], 182, 2024.

References

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economic at the Universidad de Santiago de Compostela and Senior Economist at Funcas