Spanish banks and monetary policy in 2022

With the COVID-19 pandemic still threatening economic recovery and inflation running the highest it has this century, monetary authorities in the US and Europe have taken different approaches to normalisation, with US monetary policy likely more hawkish in the short-term. Within this context, Spanish banks will continue to face acute profitability challenges in 2022, which they will increasingly seek to address through digitalisation and transition to a platform-based model.

Abstract: Monetary decoupling is already here in 2022. The Federal Reserve has set an end date for its asset purchase programme –the end of March– and signalled that rate hikes over the course of the year are likely. The European Central Bank (ECB), however, plans to continue to support liquidity until at least 2023 and does not expect to raise rates in 2022. That decoupling will have different impacts on both sides of the Atlantic, including on the ability of banks to generate margins, as well as on bond yields, exchange rates and the relative attractiveness of different monetary regions for investment. While Spanish banks have been able to increase lending capacity during the crisis on the back of state guarantee schemes and other support programs, as well as to shore up solvency, both profitability and solvency will remain key challenges in 2022, especially if rates remain ultra-low or negative and support measures are rolled back. Going forward, banks’ profitability will continue to rely to a significant degree on efficiency gains, however, after years of consolidation and structural adjustments, such gains may be achieved through greater adoption of digitalisation and the shift towards platform-based models, with implications for employee/branch rationalisation and increased investment in digitally-savvy talent.

Introduction

Still recovering from the financial crisis, Spanish banks have been put to the test with yet another challenge – the COVID-19 pandemic. Although they have increased their lending capacity (thanks to the state guarantee scheme, among other support), and shored up solvency, profitability will remain an acute challenge in 2022, especially if rates remain ultra-low or even negative. As various public stimulus and support measures put in place during the COVID-19 crisis are rolled back, the banks will need to manage their credit proactively as they are likely to face an increase in business bankruptcies.

There have been several attempts to reverse prevailing expansionary monetary policy since the financial crisis. However, the central banks have encountered a range of doubts about the dynamism of the economic recovery, which ultimately altered expectations for policy normalisation.

Still, economic performance and the scope for monetary manoeuvre have varied in the eurozone and the US. While rates have been left at 0% in the eurozone and attempts to pare back debt repurchases have been fleeting, drowned out by macroeconomic uncertainties, in the US rates have moved up and down and asset purchases have also moved in either direction. However, authorities on both sides of the Atlantic have been forced to leave their quantitative easing (QE) measures and ultra-low, zero or negative benchmark rates in place. The pandemic was the last shock to prompt the central banks to leave their support in place, probably just when they were closest to changing their orientation, towards the end of 2019.

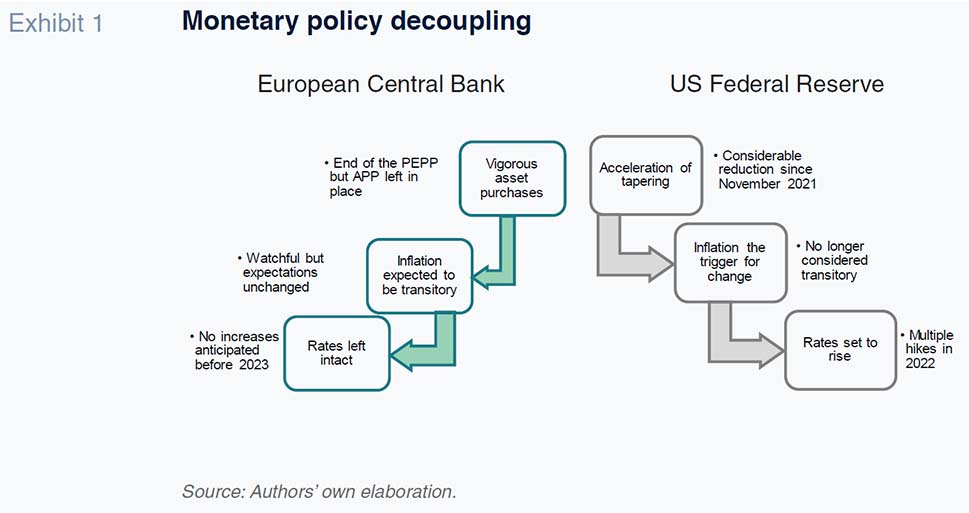

In 2022, however, it looks as if the end of QE is closer, although we are also seeing some decoupling, with the Federal Reserve announcing plans to scale back the pace of its asset purchases significantly at the end of December and, more importantly, signalling several potential rate hikes from 2022. The ECB also made statements about its monetary policy in mid-December. Conversely, it ratified maintenance of a markedly expansionary policy (beyond certain technical fine-tuning), with no signs of rate increases before 2023.

That situation implies the decoupling of monetary policy on either side of the Atlantic, which is happening at a time of inflationary pressure. It looks as if the prevailing price pressure is not set to wane any time soon, generating discord among the analysts and exerting pressure on the central banks. The key question is whether the inflation will prove fleeting or sustained, affecting medium– and long-term expectations. Although core inflation, which strips out the more volatile price elements, is not so concerning, analysts are watching closely for a potential wage price spiral. Considering that the prospect of recovery has been largely pushed back to 2022, this uncertainty is of little help.

The banks are on tenterhooks as they watch trends in inflation, interest rates and liquidity. 2021 was a challenging year in which the banks nevertheless managed to increase their market value and revisit pre-pandemic profitability levels. They also managed to keep up their private sector lending volumes. Growth in loans to businesses was joined by growth in lending to households, not only consumer loans (which were registering growth of 2.3% by November) but also, gradually, loans for home purchases (0.9% growth in November).

Regardless, the Spanish deposit-takers are facing a year in which generating margins and returns will remain a significant challenge in a climate of ultra-low or negative rates. Moreover, forecasts for the withdrawal of stimulus measures put in place to mitigate the effects of the pandemic –from furloughs to credit moratoria– could lead to an increase in bankruptcies and, ultimately, in loan non-performance.

This paper analyses the state of monetary policy, its impact on the banking sector and the outlook for the Spanish banking sector in 2022. It begins with an analysis of monetary policy decoupling and the attendant risks, followed by a focus on bank profitability and solvency. Sector consolidation and the shift towards a platform-based service model are addressed, followed by a few short conclusions.

Monetary policy decoupling

Having already made several moves and signalled the withdrawal of its stimulus measures, the Federal Reserve accelerated its actions considerably on December 15th, 2021. Following the last Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting of last year, the US monetary authority brought the definitive withdrawal of its asset purchase programme forward from June to March 2022. Although it left its official rate within a band of 0% to 0.25%, the Fed also signalled the possibility of raising rates as many as three times in 2022, the first of which in the first quarter, probably after the end of its tapering process. The Fed attributed the acceleration of its tightening to “inflation developments and the further improvement in the labor market”.

These tightening decisions came despite the downward revision of macroeconomic forecasts due to the surprise appearance of the Omicron variant of the coronavirus. In 2022, the Fed is looking for GDP growth of 4% and inflation of 2.6%. The key is whether prices will hit such a low average rate with monthly rates topping the 6% mark towards the end of 2021. According to the Fed, “Supply and demand imbalances related to the pandemic and the reopening of the economy have continued to contribute to elevated levels of inflation” and “The path of the economy continues to depend on the course of the virus. Progress on vaccinations and an easing of supply constraints are expected to support continued gains in economic activity and employment as well as a reduction in inflation.” It warned, however, that “Risks to the economic outlook remain, including from new variants of the virus.”

More specifically, the FOMC decided to reduce the monthly pace of its net asset purchases by 20 billion dollars for Treasury securities and 10 billion dollars for agency mortgage-backed securities. As tends to be the case when providing testimony in times of uncertainty, the Federal Reserve also signalled its willingness to “adjust the stance of monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge that could impede the attainment of the Committee’s goals.”

One day later, on December 16th, the ECB’s Governing Council held its last meeting of 2021. Despite the run-up in prices, the ECB said it judges that “the progress on economic recovery and towards its medium-term inflation target permits a step-by-step reduction in the pace of its asset purchases over the coming quarters.” The ECB was referring, however, to a reduction in the dedicated pandemic emergency purchase programme, or PEPP. Indeed, it noted that “monetary accommodation is still needed for inflation to stabilise at the 2% inflation target over the medium-term.” It announced that it would be discontinuing net asset purchases under the PEPP at the end of March 2022, but that it would reinvest the maturing principal payments from securities purchased under the PEPP until at least the end of 2024.

In parallel, the ECB ratified the continuity of its main asset purchase programme (APP). Specifically, the Governing Council settled on a monthly net purchase pace of 40 billion euros in the second quarter and 30 billion euros in the third quarter under the APP. From October 2022 onwards, the Governing Council will maintain net asset purchases under the APP at a monthly pace of 20 billion euros for as long as necessary to reinforce the accommodative impact of its policy rates. With that, the European monetary authority signalled that while it could reduce its asset purchases more significantly in the long-term, it was guaranteeing their continuity in 2022, along with the reinvestment of principal payments from maturing securities for as long as necessary.

As for interest rates, the ECB decided to leave the interest rate on the main refinancing operations, and the interest rates on the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility, unchanged at 0.00%, 0.25% and -0.50%, respectively. According to the monetary authority, despite the rise in prices, the “realised progress in underlying inflation is sufficiently advanced to be consistent with inflation stabilising at 2% over the medium-term.”

Lastly, the ECB said it expects the special conditions applicable under TLTRO III to end in June 2022 but, as on prior occasions, it reiterated its intention to monitor the two-tier system for reserve remuneration and extend the programme if necessary.

As shown in Exhibit 1, medium– and long-term tightening trends appear to be taking shape on both sides of the Atlantic, but in the short-term, US monetary policy is likely to be far more hawkish, creating considerable monetary policy decoupling. For the banks, that could spell ongoing downward pressure on the European banks’ net interest income relative to their US peers.

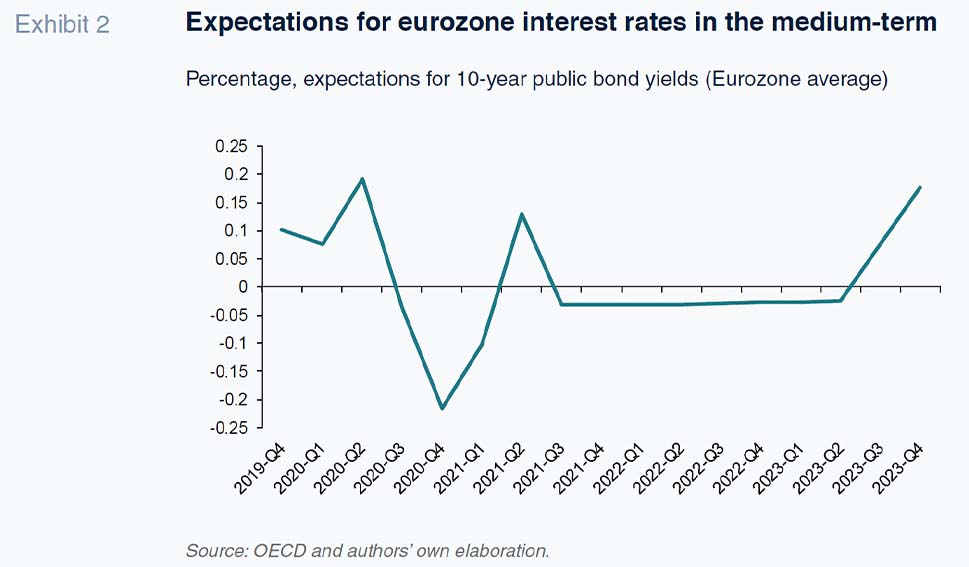

The Fed could raise rates up to three times in 2022, while the ECB is not planning to make any rate moves. Nevertheless, the expectation is that the eurozone could finally implement its long-anticipated monetary policy shift in 2023, after nearly 15 years of quantitative easing. As illustrated in Exhibit 2, based on estimates of long-term rate expectations (using 10-year sovereign bond yields as proxy), although the shift in the eurozone is expected to take longer, the rate movements anticipated in 2023 are considerable, with impacts on both short- and longer-term paper. Exhibit 2 depicts estimated average yields on 10-year public bonds in the eurozone member states, which are expected to rise to close to 0.2% that year.

Post-pandemic banking (I): Profitability and solvency

The Spanish banks have been very active in keeping credit flowing throughout the pandemic. The banks, the regulators and the supervisors all understood very early on that it was necessary to strike a balance between the risks of the lending business and the need to support the business communities most affected by mobility and business restrictions.

The programme of loans backed by Spain’s official lending institute, the ICO, has played a vital role throughout the pandemic: by November 2021, 121.92 billion euros of financing had been extended under the scheme. That scheme was topped up by a surety line for direct investments in July 2021 of up to 40 billion euros. Another essential component articulating the financial “arm” of the pandemic response is credit moratoria, underpinned by a code of good practices designed to allow financial institutions to defer the repayment of eligible loans, framed by strict liquidity facilitation and risk prevention criteria.

Loans to businesses were up by 2.5% year-on-year as of September 2021, having hovered between 2% and 3% since April. Although growth had been higher earlier on in the pandemic crisis (fuelled by the initial tranches of the state loan guarantee scheme), it is worth recalling that business lending contracted by 0.1% on average in 2018 and registered growth of 1.9% in 2019. Household lending was also starting to show signs of life by the third quarter, with lending up 0.8% in September, in line with the readings observed since May, putting an end to more than 18 months of contraction during the worst moments of the pandemic. That momentum was observable not only in the consumer loan segment, which sustained growth of 3.1%, but also in the home finance segment, which registered year-on-year growth of 0.7% in the third quarter of 2021.

The ultimate impact of these actions on solvency remains unknown: only when the stimulus and other measures rolled out to support businesses and jobs (such as the furloughs) are withdrawn will it be possible to calibrate how many business casualties result from the pandemic crisis and how many surviving firms will not be able to service their loan obligations. Regardless, sector supervisors argue that the reforms undertaken to address unsustainable leverage levels in the banking system, insufficient tier-1 capital levels, excessive maturity transformation and shortcomings in the macroprudential framework have proven crucial during the COVID crisis.

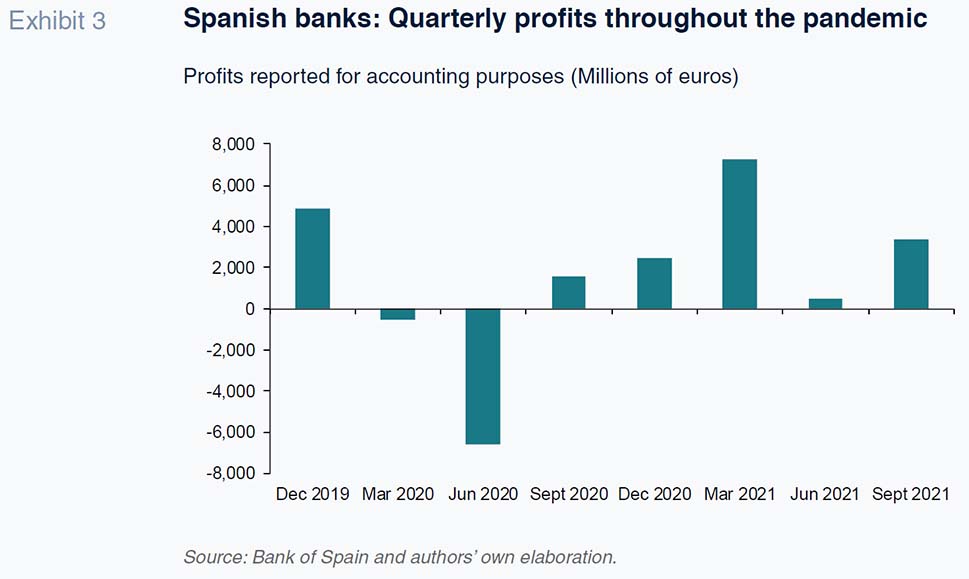

Just as the ECB was considering a switch in monetary policy direction towards the end of the second half of 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic forced monetary authorities to leave their expansionary policies in place. When interest rates are consistently low, the banks face a structural issue of depressed profitability. However, the pandemic ushered in an even bigger challenge. The Spanish banks responded proactively, significantly stepping up their provisions against potential losses, an effort that drove the sector’s quarterly profitability lower by 6.61 billion euros in the second quarter of 2020, as shown in Exhibit 3. In 2021, the banks’ earnings gained momentum, albeit somewhat erratically due to the impact of new variants of the virus and the sector’s structural adjustments. Sector profitability in the third quarter of 2021 amounted to 3.35 billion euros.

It is also worth pointing out that the Spanish banks’ market cap has rallied notably since the end of October 2020, with the gap between the IBEX banks and the rest of Spain’s blue chip index gradually closing. By the end of February 2021, the IBEX banks were outperforming the rest of the IBEX-35. However, the banks did not revisit their pre-COVID market value until the end of April 2021.

Post-pandemic banking (II): Consolidation and a shift in the business model

The Spanish banking sector has undergone significant restructuring since the financial crisis. In early 2008, there were 281 banks (70.8% of which were Spanish), a figure that had shrunk to 191 by the end of 2020 (58.6% Spanish). Following the financial crisis, certain banks had to embark on mergers to survive the tightening of their capital adequacy requirements. That consolidation has gained further traction due to the demands of an increasingly digital market that requires significant scale, but not necessarily an extensive physical infrastructure.

In 2021, sector restructuring continued in Spain with high-profile mergers, such as those between Caixabank and Bankia (March 2021) and between Unicaja and Liberbank (July 2021). That restructuring process has driven a change at both the entity and branch levels. In 2014, there were 31,817 bank branches in Spain, an average of 230 per bank. By the end of 2020, 22,299 branches remained. In other words, one in four of the branches in existence in 2014 had disappeared. In the first half of 2021 alone, 1,385 branches were closed, mainly due to mergers. By the same token, in 2014, the sector had 203,305 employees. In 2020, that figure was 175,185.

It is also worth noting that the average employee, or talent, profile has changed. Digital transformation is fuelling demand for highly qualified professionals. In the Spanish banking sector, there is growing demand for professionals with a technical background –computer engineers, data scientists and mathematicians– capable of developing applications to manage IT systems, business processes and quantitative risk models. Some global forecasters predict that between 15% and 20% of new positions will be related with digitalisation.

Spanish banks are going to lengths to transform their businesses and adapt to the new digital ecosystem in terms of providing a platform-based service offering. The COVID-19 pandemic has also driven growth in online customers. A comparison of figures from before the pandemic (end of 2019) with those at year-end 2020 reveals that the percentage of digital customers has increased by six percentage points from 60.5% to 66.6%, according to the INE. This means that, in the year after 2019, 2.7 million new people signed up for digital banking in Spain.

The financial digitalisation process has not, however, been homogeneous. There are significant differences in penetration rates across the various age categories. The highest percentage of digital banking users are in the 25–34 age group. In that category, nearly eight out of every ten internet users have adopted online banking. The figure is similar (75.5%) in the 35–44 cohort. Those two age categories represent the millennial generation and account for 9.48 million online banking users, which is 43.3% of the total in Spain.

In the past two decades, the Spanish banking sector has made major strides in digitalisation. Banks have stepped up their technology investments considerably and attracted new online customers, which has in turn spurred them to make new investments in emerging technology. Between 2014 and 2020, the ratio of investment in information technology in the Spanish banking sector averaged 4.97%. On a cumulative basis, IT investments registered growth of 71.78% between 2014 and 2020 (last year for which data are available).

Conclusions

Faced with specific challenges in 2022 and with inflation running at a high for this century, the Federal Reserve and ECB have taken different approaches. The US monetary authority has quickly ceased to consider the current bout of inflation a transitory phenomenon, moving to tackle it head on, bringing the end of its asset purchase programme forward to the end of March 2022 and signalling several possible rate hikes this year. Meanwhile, the ECB may pare back its asset purchases over the medium– or longer-term, but is planning to leave its liquidity support in place until at least 2023 and does not intend to raise rates in 2022.

Which strategy will prove correct is difficult to predict, but we are certainly facing monetary policy decoupling that will have a different impact on multiple aspects of financial activity on either side of the Atlantic, including the banks’ ability to generate net interest income, as well as on bond yields, exchange rates and the relative attractiveness of each monetary region for investment purposes.

The profitability of banks continues to rely to a significant degree on operating efficiency gains. After years of sector consolidation and structural adjustments, there seems to be a fresh twist in the transition to a platform-based model. Further branch and employee rationalisation are likely, and banks will be looking to bring in new digitally-savvy talent on both the sales and technical sides of the business in parallel.

Santiago Carbó Valverde and Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas