Recovering from the pandemic: The role of the macroeconomic policy mix

A new emphasis on policy coordination to mitigate the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic led to a faster than expected European economic recovery, particularly compared to the Global Financial Crisis. However, policy coordination is still a challenge and will require a clear understanding of an unfamiliar economic context, together with strong agreement among European policymakers.

Abstract: European policymakers learned important lessons about the need for monetary and fiscal policy coordination from the Global Financial Crisis, which they applied at the start of the pandemic. The resulting recovery has been faster than expected, despite successive waves of variants. However, learning these policy lessons has not eliminated the many barriers to policy coordination, especially when there is disagreement among policymakers over macroeconomic performance, assignment of policy instruments to economic targets and concerns about policy interaction. Unfortunately, the pandemic economic recovery has fostered such a context, as have efforts to respond to demographic change, global warming and digital innovation. Under this scenario, successful policy coordination will require both careful analysis of what is clearly an unfamiliar economic situation and strong political agreement on what European policymakers should do about it.

Introduction

The macroeconomic recovery from the economic consequences of the pandemic has been faster than expected, despite successive waves of variants. It is particularly fast compared to the recovery from the global economic and financial crisis. Forecasters expect most European economies to return to pre-pandemic levels of gross domestic product (GDP) and unemployment by the second quarter of 2022 (if they have not done so already). [1] That is just eight quarters after the shock. They expect the eurozone to reach pre-pandemic trends in real GDP growth by the end of the year. [2]

By contrast, recovery from the economic crisis took at least a decade for much of Europe. [3] In some countries, such as Italy, the economy had not recovered before COVID-19 struck. As Eurogroup President Paschal Donohoe explains, the difference is “to a large extent due to the coordinated policies we deployed to mitigate the economic consequences of the pandemic. It is a reminder that coordinated action achieves more than individual efforts.” [4] He is no doubt correct that macroeconomic policy coordination would have been important in the last crisis, where it did not happen, and in the present crisis, where it did. What is less clear is whether European policymakers can now take successful policy coordination for granted.

A lack of coordination

Policymakers have long recognised coordination as important, both within and between countries (Cooper, 1968). Still, coordination is often difficult, and the global economic and financial crisis was, in many ways, a case study of the challenges we are facing now. The policymakers who confronted the initial shockwaves in 2007 and 2008 could recognise the tensions in financial markets; somewhat belatedly, they could also imagine how these tensions might have an impact on growth and employment. Nevertheless, they failed to anticipate how monetary policy would interact with fiscal policy, either directly in terms of how monetary policy is connected to sovereign debt markets, or indirectly in terms of where monetary and fiscal policymakers should focus their attention, and how those targets would interact.

This confusion is complicated enough that only a book-length treatment can unpack it completely (Tooze, 2018). The easiest way to illustrate the tensions is to point to moments of policy failure. For the European Central Bank (ECB), the obvious examples are in the late autumn of 2007 and summer of 2008, when the Governing Council chose to tighten its collateral rules (to restrict the expansion of credit and lower the risk on its own balance sheet) and to focus on inflation rather than financial stability by raising its policy rates. [5] Both moves had to be reversed in September 2008 when the US investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed.

These monetary policy actions were not only misdirected in terms of macroeconomic performance. They also shifted much of the burden for macroeconomic stabilisation onto the automatic stabilisers built into fiscal policy, as the sudden slowdown in activity lowered taxes, while the increase in unemployment drew down benefits. Meanwhile, the reversal of European monetary policy following Lehman was not enough to blunt the impact of the crisis on government debts and deficits. Worse, it was inconsistent. The Governing Council tried again to raise its policy rates in the summer of 2011. [6] Again, that policy move had to be put into reverse.

The story on the fiscal side was complicated, too. Fiscal policymakers were quick to recognise the contribution of automatic stabilisers to mitigating the impact of the crisis. Nevertheless, they worried that excessive reliance on those automatic features of taxes and transfers would result in lasting structural imbalances that could create unsustainable debt burdens (Schäuble, 2010). As a result, European fiscal policymakers began to tighten the rules for fiscal policy coordination to focus on long-term debt sustainability, even if this meant reducing the effectiveness of automatic fiscal stabilisers in supporting macroeconomic performance and preventing fiscal authorities from intervening effectively to shore up banks and, therefore, ensuring financial stability (Schmidt, 2020).

The effect of this shift in fiscal policy was to push much of the burden for financial stability and macroeconomic performance back onto the ECB. National fiscal authorities might try to play a more active role, but those countries already in distress quickly lost credibility among financial market participants (Hopkin, 2015). This explains why ECB President Mario Draghi promised to do “whatever it takes” to safeguard the euro in July 2012, even if that meant buying up unlimited amounts of sovereign debt from those countries most affected. It also explains how the ECB moved ever further into an unconventional monetary policy stance as the recovery from the global economic and financial crisis failed to materialise and involved both large-scale asset purchases and negative deposit rates.

The ECB’s actions were sufficient to bring an end to the most acute phase of the European sovereign debt crisis, but they were not enough to promote a durable economic recovery. That is why the last major policy moves by the Governing Council prior to the pandemic were to add to its unconventional monetary stimulus. It is also why the leadership of the ECB began to advocate openly for greater European fiscal authority (Jones, 2019).

Despite Europe’s relatively poor macroeconomic performance more than 10 years after the start of the crisis, European policymakers did not agree on how coordination across policy instruments would strengthen macroeconomic governance. More fundamentally, they disagreed on how the different instruments should be targeted and what those settings could realistically accomplish. Meanwhile, some policymakers grumbled about how the ECB’s unconventional policy stance would lead to monetary dominance over fiscal policy, while others worried that excessive commitment to fiscal consolidation was tying the hands of monetary policymakers.

A new beginning

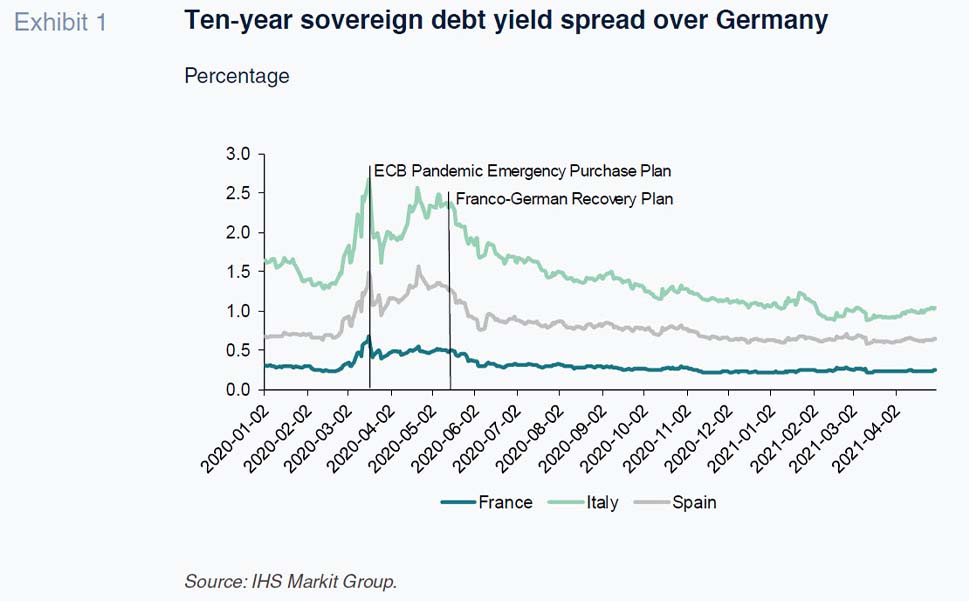

The onset of the pandemic changed the conversation fundamentally, but not immediately. During the early weeks of the pandemic, the old arguments about monetary dominance and fiscal austerity continued to resurface (Howarth and Quaglia, 2021). The results of this ongoing disagreement were sometimes dramatic, as when ECB President Christine Lagarde insisted that it was not the bank’s job to “close the spread” between sovereign borrowing costs in those countries worst hit by the pandemic and those in other parts of the eurozone (Exhibit 1). The older debates could also be heard in Dutch Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra’s call for an investigation into why some of the southern European governments were not on better fiscal footing at the start of the pandemic. The reaction to this call from other parts of Europe played an important role in changing the tenor of the conversation (Jones, 2021a).

Policymakers both in the ECB’s Governing Council and in the Eurogroup of finance ministers began to focus more attention on finding ways to strengthen the impact of monetary and fiscal policy on macroeconomic performance and to ensure that the two sets of instruments work together in a complementary fashion.

This new emphasis on coordination resulted in significant innovations. The ECB’s Governing Council began to purchase sovereign debt more flexibly to ensure the smooth functioning of the monetary transmission mechanism (hence “closing the spreads”); it also began to use its deposit rate and long-term lending operations in a way that would directly subsidise bank lending to the private sector. At the same time, the Eurogroup empowered the European Commission to borrow funds directly from the markets to use in supporting Member State employment protection schemes and it worked closely with the European Stability Mechanism and the European Investment Bank to ensure that both governments and firms had access to other emergency sources of credit.

Not all innovations were equally successful (or attractive). What matters is that they all pointed in the same direction as monetary authorities targeted credit creation and financial market stability, while fiscal authorities stabilised incomes, consumption and investment. The creation of an even larger recovery and resilience facility (Next Generation EU) was the last step in this process. This innovation was important to ensure that the benefits of macroeconomic policy coordination extended symmetrically across the European Union, both inside and outside the single currency. It also signalled a fundamental shift in the debate away from a narrow focus on monetary or fiscal dominance and toward a more coordinated approach to macroeconomic stabilisation. Hence, the Franco-German proposal to enhance the European Commission’s borrowing capacity in May 2020 had a major impact on bond markets (Jones, 2021b).

This change in the conversation was possible because policymakers had a shared understanding of the macroeconomic situation. When European leaders locked down their populations to minimise the spread of COVID-19, they knew this would shut down significant areas of economic activity, strain household and corporate balance sheets, depress prices and complicate government borrowing. They also knew that the ability of monetary authorities to stabilise economic performance without fiscal support was limited, and they knew that the ability of Member State governments to provide that fiscal support varied significantly across countries. Although this common understanding was not universal –there were important differences among Member State governments (Jones, 2021a)– it was shared widely enough to form the basis of an effective (and innovative) macroeconomic policy mix (Rhodes, 2021).

Macroeconomic policymakers also had a shared understanding of how monetary and fiscal policy would interact. The massive purchase of sovereign debt by the ECB pushed up bond prices and drove down interest rates, making it easier for governments to borrow and to sustain higher levels of debt. In turn, government borrowing not only supported higher levels of economic output and employment, but also helped to stabilise market expectations about future price inflation. This made it more likely that the ECB would meet its primary policy objective of price stability as defined, at that time, in terms of an expected annual inflation rate of below but close to two percent.

Finally, the combination of lending subsidies in the form of long-term refinance operations, income support measures and state aid helped to underpin financial market stability. In this way, the macroeconomic policy mix was complementary across multiple dimensions, as the different instruments reinforced one another and strengthened underlying macroeconomic performance. European policymakers like Donohoe are justifiably proud of their accomplishments.

Why coordination is difficult

The macroeconomic policy mix played an essential role in promoting Europe’s economic recovery during the pandemic. Reliance on expansive European monetary policy and national fiscal efforts at the start of the crisis was not enough to stabilise either macroeconomic performance or market sentiment. Only the promise of European fiscal action was able to help turn the corner, particularly in sovereign debt markets, but also, somewhat later, in consumption, investment and employment (Jones, 2021b).

Nevertheless, the formula for coordinating the use of macroeconomic policy instruments is not obvious. The macroeconomic policy mix is more than just a matter of ensuring that monetary policy works together with fiscal policy. It is also a question of ensuring that both monetary policy and fiscal policy have stabilising effects on macroeconomic performance. More importantly, it is about ensuring that the different instruments stabilise different aspects of macroeconomic performance. This division of labour across macroeconomic policies is Jan Tinbergen’s famous injunction that each instrument should be assigned a different macroeconomic target.

What Tinbergen’s assignment problem implies –and this is most important– is that policymakers have a shared understanding of how the different variables they target, like output and employment, or inflation, interact in the real economy (Kydland, 1969). Where policymakers do not share that understanding, it is hard to see how they can coordinate their settings across policy instruments effectively. Instead, it is easy to see how they might become concerned about the influence that one set of policies –say, monetary or fiscal– will have on the freedom of movement for the other.

This is how talk of the macroeconomic policy mix quickly devolves into conversations about monetary or fiscal dominance. The concerns focus less on complementarity and more on relative constraint. Political considerations penetrate easily into such conversations; along the way, more technical concerns take on an ideological appearance. As a result, whatever lessons policymakers may have learned about the virtues of working together during a crisis tend to lose force in the battle between competing models of how the macroeconomy works (Matthijs and Blyth, 2018).

This time is different

The onset of the pandemic was a rare moment where agreement among economic policymakers was relatively easy; the reason is that those policymakers –through the introduction of social distancing requirements and lockdown measures– were the source of the economic shock. They may have disagreed about the implications of lasting supply chain disruption or about the necessity to introduce specific measures, but they could not argue with the fact that the effect of such lockdowns –either domestically or in key partner countries– would have profound consequences for output, employment and prices (Cifuentes-Faura, 2021).

That easy consensus on how the economy works has not survived the recovery. This is due, at least in part, to the newness of the situation. No economist has ever experienced the kind of global restrictions that policymakers introduced to slow the spread of the virus, and so none has a clear model of how the world economy will perform as social distancing requirements are relaxed (Chen et al., 2020). The first challenge was to restore public confidence that any loosening of social distancing requirements would not constitute a health threat (Demirgüç-Kunt, Lokshin and Torre, 2021).

Beyond that psychological element, the list of distortions runs from the displacement of shipping containers and the accumulation of household savings during the lockdown, to the shift from spending on services to manufacturing, the movement from retail shopping to home delivery and the rise of digital commerce. They also include the increase in remote or hybrid working practices, the accelerated globalisation of business-to-business service provision and the relocation of workers from urban to suburban or rural communities. Such changes not only resulted in a redistribution of capital across vast sectors of the economy, but also created important shortages in labour, intermediate components and raw materials required by those sectors that gained most from the redistribution.

To make matters more complicated, the effects of the pandemic came alongside longer term developments related to population ageing, climate change and technological innovation. Hence, governments seeking to respond to the crisis had to, at the same time, reengineer public services to meet the needs of different demographics, lower energy use, encourage recycling and introduce the infrastructure necessary for a more sustainable, digital economy. Given that these projects are at the centre of the European Union’s recovery and resilience planning, there is consensus that these transitions require investment.

There is little consensus, however, on whether and how the investments required will have an impact on macroeconomic performance (Genberg, 2020; Pisani Ferry, 2021). While the spending should stimulate economic activity, the implications for longer-term productivity growth and price inflation remain ambiguous. More optimistic models suggest a movement to a new, stable equilibrium; others point to increased volatility in the near-term and greater uncertainty across longer time horizons.

Such uncertainty has powerful implications for macroeconomic policy coordination as it affects considerations of both near-term inflation performance and longer term debt sustainability. The conversations about inflation performance already divide the ECB’s Governing Council, with prominent members of the Executive Board arguing that currently high rates of inflation are only temporary, while more hawkish national central bank governors express concern that high inflation rates may prove to be more permanent. [7] There are similar debates within the Eurogroup, which is focusing on reforming the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination. Here, the question is whether interest rates will remain low enough to make higher levels of public debt sustainable or whether it would be more prudent to bring in consolidation efforts sooner rather than later (Smith-Meyer, 2021).

Importantly, the two debates are connected. Monetary policymakers worry that the pressure to underpin debt sustainability might hamper the fight against longer-term inflation rates, and fiscal policymakers worry that efforts to push back against inflation might trigger fiscal austerity. The question is not just between competing macroeconomic models; it is also over the prospect of fiscal dominance or monetary dominance.

Recovery and the policy mix

European policymakers learned important lessons from the global economic and financial crisis, and they applied those lessons at the start of the pandemic. The resulting recovery has been much stronger than most policymakers expected initially. This is an important success. However, these policy lessons only underscore the importance of coordination in principle. In practice, it does not eliminate the many challenges that can prevent policy coordination from being implemented successfully. When policymakers disagree on how macroeconomic performance is likely to develop, where they question the assignment of their policy instruments to targets in the real economy and where they worry that the interaction across policies will lead to the dominance of monetary policy over fiscal policy or the reverse, the incentives for coordination –no matter how desired or well-intentioned– are diminished.

Unfortunately, the recovery from the economic consequences of the pandemic has created such a context, as do efforts to respond to demographic change, global warming and digital innovation. The conclusion is not that successful policy coordination to stabilise the recovery and smooth the transition is impossible. Rather, it is that such coordination cannot be taken for granted. It will require both careful analysis of what is clearly an unfamiliar economic situation and strong political agreement on what European policymakers should do about it.

Notes

Again, see Donohoe’s letter to the European Council President.

References

CHEN, S.,

et al. (2020). Tracking the Economic Impact of COVID-19 and Mitigation Policies in Europe and the United States.

IMF Working Paper WP/20/125. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

CIFUENTES-FAURA, J. (2021). Analysis of Containment Measures and Economic Policies Arising from COVID-19 in the European Union.

International Review of Applied Economics, 35(2), pp. 242–255.

COOPER, R. (1968). The Economics of Interdependence. New York: McGraw Hill.

DEMIRGÜÇ-KUNT, A., LOKSHIN, M. and TORRE, I. (2021). Opening-Up Trajectories and Economic Recovery: Lessons after the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

CESifo Economic Studies, 67(3), pp. 332–369.

EBERL, J. and WEBER, C. (2014). ECB Collateral Criteria: A Narrative Database 2001–2013.

IFO Working Papers, 174. Munich: IFO, February.

GENBERG, H. (2020). Digital Transformation: Some Implications for Financial and Macroeconomic Stability.

ADBI Working Paper Series, 1139. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

HOPKIN, J. (2015). The Troubled Southern Periphery. In M. MATTHIJS and M. BLYTH (eds.),

The Future of the Euro. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 161–185.

HOWARTH, D. and QUAGLIA, L. (2021). Failing Forward in Economic and Monetary Union: Explaining Weak Eurozone Financial Support Mechanisms.

Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), pp. 1555–1572.

JONES, E. (2009). Do Central Bankers Dream of Political Union? From Epistemic Community to Common Identity.

Comparative European Politics, 17(4), pp. 530–547.

JONES, E. (2021a). Hard to Follow: Small States and the Franco-German Relationship.

German Politics. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.2002300JONES, E. (2021b). Next Generation EU: Solidarity, Opportunity, and Confidence.

European Policy Analysis 2021:10epa, June.

KYDLAND, F. (1969). Decentralized Stabilization Policies: Optimization and the Assignment Problem.

Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, 5(2), pp. 249–261.

MATTHIJS, M. and BLYTH, M. (2018). When Is It Rational to Learn the Wrong Lessons? Technocratic Authority, Social Learning, and Euro Fragility.

Perspectives on Politics, 16(1), pp. 110–126.

PISANI FERRY, J. (2021). Climate Policy is Macroeconomic Policy, and the Implications Will Be Significant.

Policy Brief, 21–20, August.

RHODES, M. (2021). “Failing Forward”: A Critique in Light of Covid-19.

Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), pp. 1,537–1,554.

SCHÄUBLE, W. (2010). Maligned Germany is Right to Cut Spending.

Financial Times, 23 June.

SCHMIDT, V. (2020).

Europe’s Crisis of Legitimacy: Governing by Rules and Ruling by Numbers in the Eurozone. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

SMITH-MEYER, B. (2021). Hopes of EU Fiscal Reform on the Rocks after Pushback from Eight Capitals.

Politico, 9 September.

TOOZE, A. (2018).

Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crisis Changed the World. New York: Penguin.

Erik Jones. Professor and Director of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute