Outlook for the Spanish economy in light of rising inflation

As the COVID-19 pandemic drags on, Spain is grappling with a sharp rise in inflation brought on mainly by higher electricity and energy prices. While inflation is a major risk, we are forecasting continued recovery in 2022, with GDP expected to reach pre-pandemic levels by the start of 2023, underpinned by the assumption of a slowdown in energy-price inflation beginning in the spring.

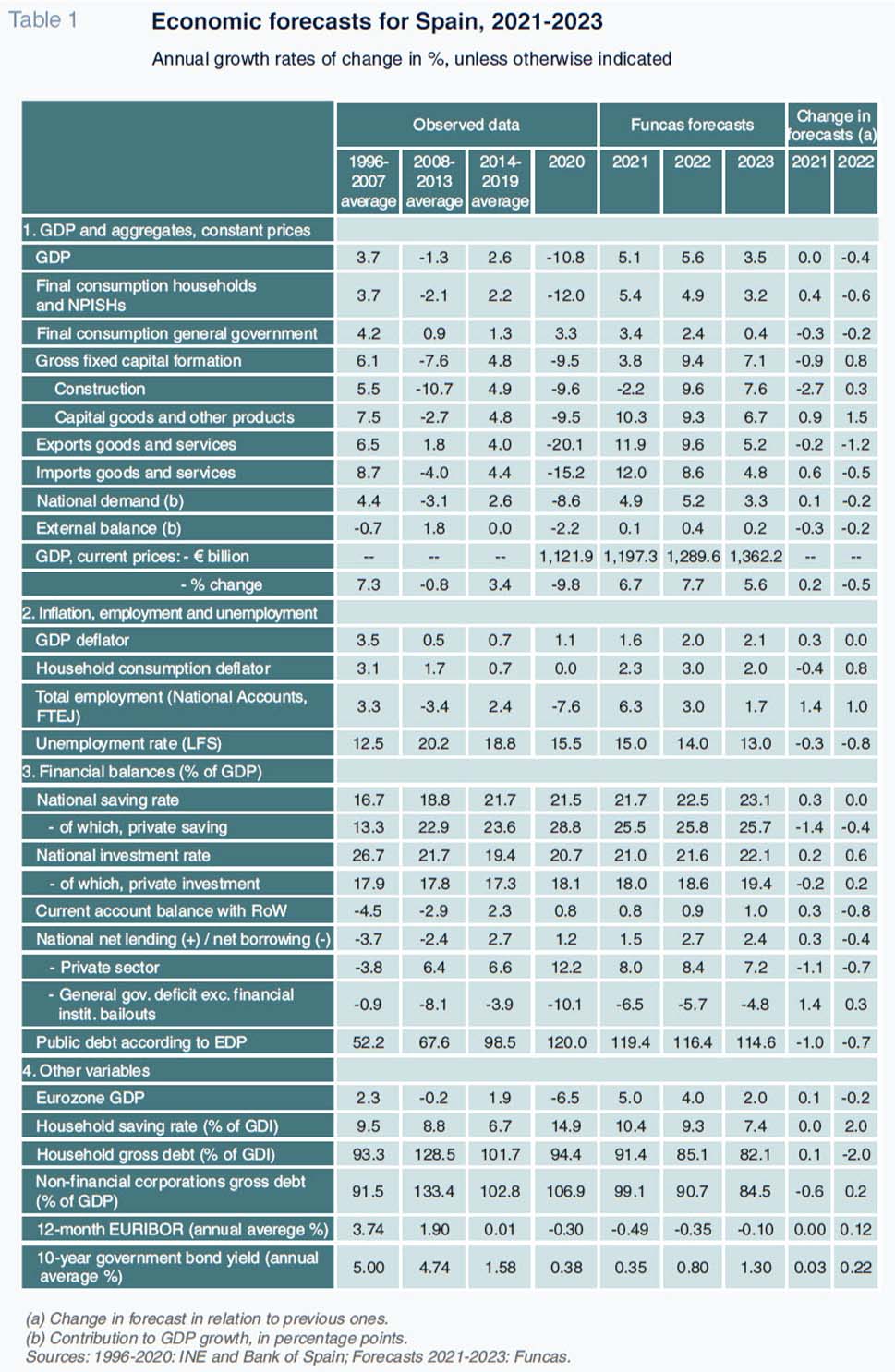

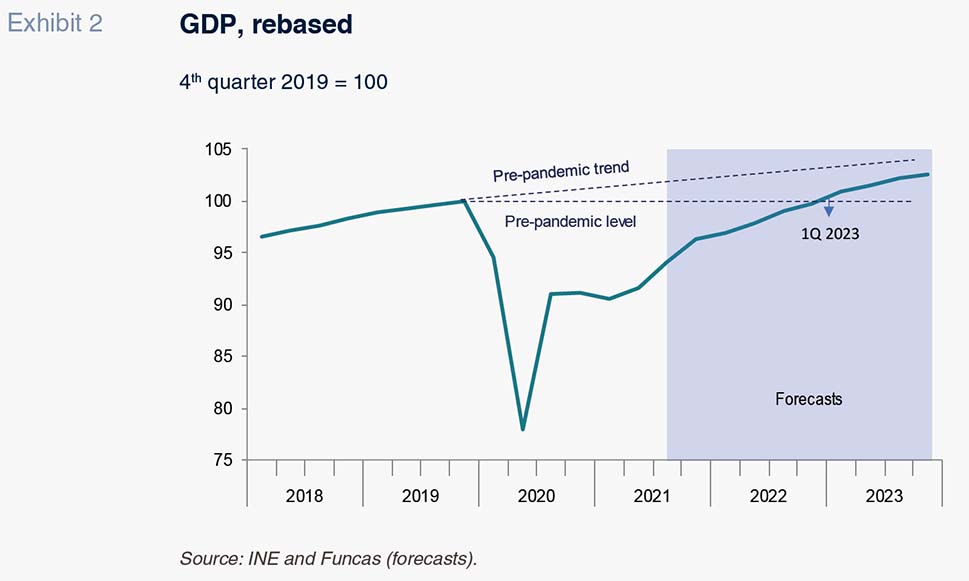

Abstract: The economy is expected to have grown by 5.1% in 2021, lower than initial expectations. The shortfall is stemming mainly from a weaker than projected recovery in consumption –as higher prices eroded purchasing power– and adverse investment trends in construction, together with a slower than anticipated execution of NGEU funds. In general, rising inflation has become one of the main threats facing the Spanish economy. The emergence of bottlenecks in 2021 drove production costs higher, curbing the rebound in economic activity. Going forward, although the reconfiguration of global supply chains should offset price increases, other inflationary pressures could last throughout the projection horizon. Of particular concern are developments in the energy markets as well as second-round effects. Our central scenario is still for strong GDP growth of 5.6% in 2022, fuelled primarily by both domestic demand, notably investment in construction and capital goods, and favourable export performance. Although this rebound is likely to lose momentum in 2023, growth is still forecast to reach 3.5%, which would put GDP back at pre-pandemic levels by the first quarter of that year. That said, this scenario rests on the evolution of inflation trends. Indeed, higher than projected prices would have a significant negative effect on real incomes and the strength of the recovery.

Recent trends and 2021 in review

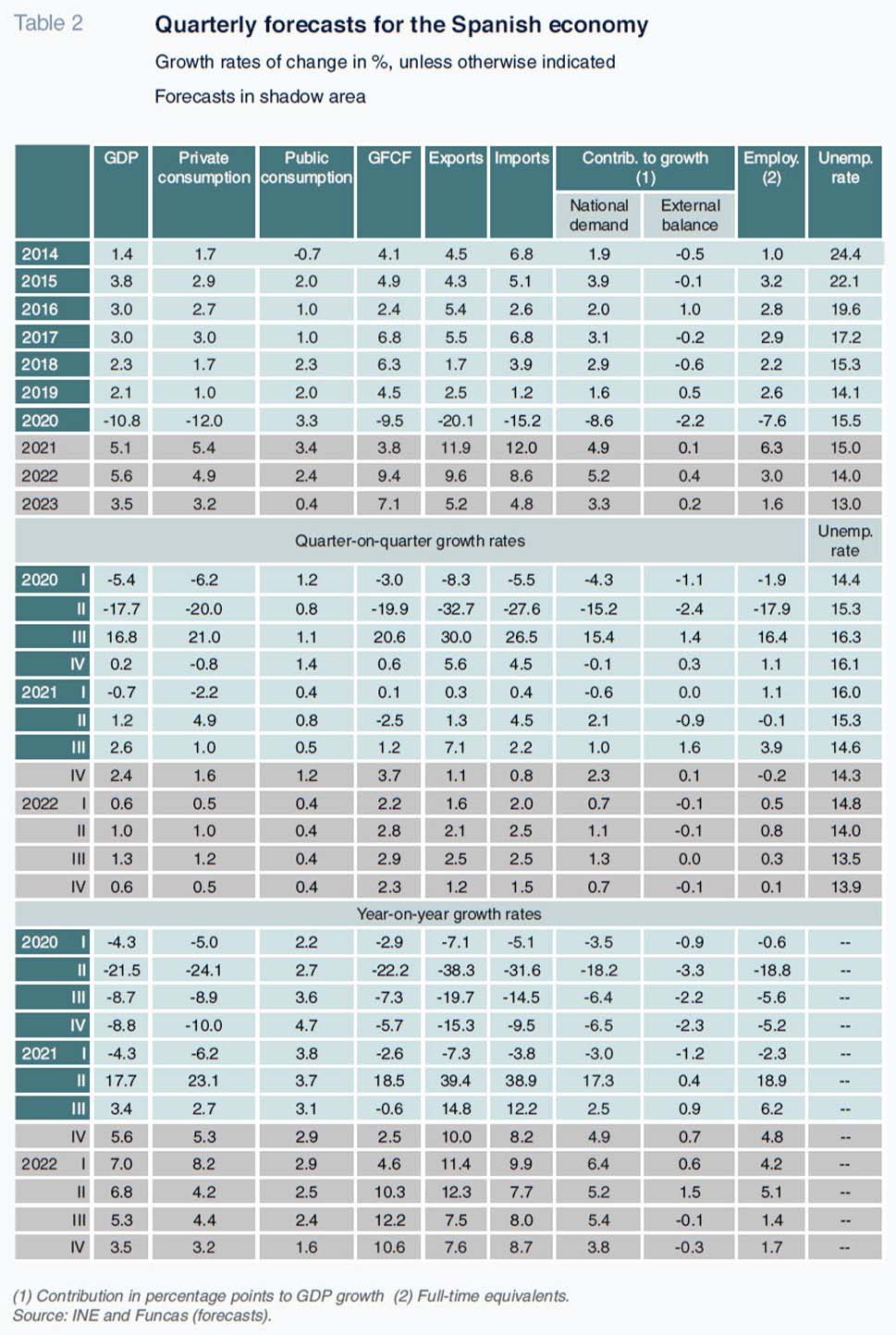

Following the upward revision of the third-quarter GDP growth figure to 2.6%, the economic indicators out so far suggest that fourth-quarter growth will align with expectations. Some of those indicators, including retail sales, the industrial production index (IPI) and turnover at large enterprises, which had been languishing for much of the year, sustained sharp improvements in November, while tourist arrivals also continued to recover. Goods exports, based on sales reported by large enterprises, also registered growth in October and November.

There is more uncertainty regarding the economy’s performance in December due to the potential impact of the new Omicron variant. In industry, the manufacturing PMI continued its downtrend, peaking in August but remaining at high levels. Meanwhile, manufacturing sector confidence and order indices improved. In the services sector, however, the PMI suffered a considerable setback and confidence deteriorated, suggesting the impact of Omicron may be limited to the services sector.

Elsewhere, job creation remained strong throughout the fourth quarter, judging by Social Security contributor reports. Although the monthly rate slowed in December compared with the average recorded throughout the second half, growth was still high by historical standards. As was the case throughout the second half of the year, the fourth-quarter growth in contributors was fuelled mainly by the private sector, which registered 3.6% quarter-on-quarter growth in contributors, including the people brought out of furlough.

We are reiterating our estimate for 2021 GDP growth of 5.1%, which is lower than we had been forecasting at the start of last year. The factors placing downward pressures on our original estimates ultimately had a greater than anticipated impact, particularly those related to the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination developments around the world, the boost in consumption from the release of surplus savings pent up in 2020 and the execution of investments under the scope of the Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme.

In sum, the shortfall in GDP growth in 2021 relative to expectations stemmed mainly from a weaker than projected recovery in consumption and an adverse trend in investment in construction. Execution of the NGEU funds was also slower than the assumptions we had made at the start of the year. International tourism, on the other hand, performed in line with those initial assumptions.

In contrast with the slower than forecast output growth, job creation was more dynamic than we were expecting in 2021, outpacing growth in GDP. Employment, measured in terms of effective contributors, registered growth of 8.8% by comparison with 2020. Measured in terms of the number of hours worked, pending release of the fourth-quarter 2021 figure, the estimated growth narrows slightly to a little over seven per cent. Comparing those figures with our estimate for GDP growth of 5.1% suggests a significant loss of productivity, which is expected to prove transitory and to correct over the course of 2022 and start of 2023.

A final noteworthy characteristic of Spain’s recent economic performance has been the sharp increase in inflation. Inflation started 2021 at very low levels, at close to zero, and ended the year at 6.7%. During the first half of the year, inflation was fuelled by energy, specifically the recovery in oil prices in the wake of the corrections sustained in 2020, and core inflation remained very subdued. From the summer onward, however, and more intensely in the final months of the year, the rise in oil prices was accompanied by sharp growth in electricity and food prices, such that core inflation also began to take off (Exhibit 1).

Core inflation ended 2021 at 2.1 per cent. The increase in the prices of food and other components of core inflation reflect higher production costs being passed on to end prices. In the case of service prices, an additional factor is lifting the inflation rate: price normalisation in certain services –hotels and tourist packages– that suffered a sharp price correction the previous year on account of the pandemic.

Outlook for 2022 and 2023

The main factors underpinning the COVID-19 recovery remain in place in relation to internal and external demand. The surplus savings set aside by Spanish households during the crisis will gradually be released, driving growth in private consumption and investment in construction, particularly in 2022. Our forecasts assume a reduction in the savings rate to 7.4% in 2023, which is close to the long-run average. Elsewhere, we expect the tendering and management of NGEU funds to accelerate and to see progress on negotiations with the European Commission on the sector-specific investment plans. Specifically, if the pace of investment against the European funds achieved in recent months were to continue, spending would increase to 24 billion euros in 2022 (of which around half was carried over from 2021), falling back to around 17 billion euros in 2023.

As for external demand, international tourist arrivals are expected to continue to recover, albeit not fully, due to lingering caution from the pandemic. We are forecasting revenue from international tourism at 80% of pre-crisis levels by the end of 2022, and of 90% by year-end 2023.

The key challenge is energy price inflation and its potential second-round effects on the Spanish economy. For this set of forecasts, we are assuming that electricity and hydrocarbon prices start to ease from the spring. According to the futures markets, gas and electricity prices are expected to come down by 15% from April, with oil prices (barrel of Brent) dipping 10% (an assumption we also layer into our baseline scenario). We are also assuming that as global supply chains recover, bottlenecks will continue to ease, making it easier for the productive apparatus to respond to growth in demand.

Based on those assumptions, we are forecasting GDP growth of 5.6% in 2022, fuelled primarily by a rebound in domestic demand, which is expected to contribute 5.2 points to that growth (Tables 1 and 2). We are forecasting a strong contribution by investment, in both construction and capital goods, thanks to the release of pent-up demand, coupled with the recovery plan stimulus measures. Household consumption is also expected to register sharp growth, shaped by the release of savings accumulated during the crisis and growth in disposable income driven by the jobs created, offsetting the loss of wage purchasing power. Public consumption is expected to ease as the spending induced by the pandemic slows.

The external sector is also expected to prove an important growth driver, making a contribution of 0.4 points. Exports of goods and non-tourism services are forecast to continue to gain market share while tourism services should benefit from the easing of travel restrictions as the vaccination drive continues around the world. Imports also look set to grow (assuming an elasticity of 1.4, which is close to the average for the period of growth that followed the financial crisis), but at a slower pace than exports.

Those growth drivers are likely to lose momentum in 2023, as the release of pent-up demand and surplus savings and the upside via recovering tourism run out of steam. Nevertheless, we are forecasting growth of 3.5%, which would put GDP back at pre-pandemic levels by the first quarter of that year (Exhibit 2). In 2023, all components of demand are expected to contribute to growth, most notably investment.

The job market should echo the economic recovery, albeit less intensely than in 2021 due to the discontinuation of “business reopening” effects. We are estimating the creation of 850,000 jobs (in FTE terms) over the next two years, which is smaller than the job creation estimated in 2021. The participation rate, meanwhile, has already revisited pre-crisis levels and additional changes are not anticipated. As a result, the improvement in employment will be echoed in the unemployment rate, which is expected to dip to around 13% by the end of the projection period. However, Spain, along with Greece, will remain one of the few EU countries with a double-digit unemployment rate, in line with the European Commission’s prognosis.

The buoyancy of demand, coupled with tension in the energy markets and supply restrictions, is expected to keep the CPI at 3.6% in 2022 (translating into a private consumption deflator of 3%) and 2% in 2023. Core inflation is similarly expected to converge towards those levels, as price increases become more widespread. The GDP deflator factors in that trend and is expected to increase to 2% in both years, the highest level since the onset of the crisis.

The rebound in inflation will cause, first of all, erosion of wage purchasing power in real terms of 3% throughout the overall projection period. Unit labour costs, meanwhile, are expected to decrease by around 2% during the two-year period. In light of the increases sustained in 2020–2021, those costs would still remain above pre-crisis levels.

Secondly, we think investors will demand higher returns for holding government bonds, as they are already doing in the US where inflationary pressures are considerably more pronounced. We are forecasting the yield on 10-year Spanish bonds at around 1.5% by the end of 2023, making the negative rates observed last year a thing of the past. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank (ECB) is expected to continue to normalise its monetary policy, specifically paring back its public bond purchases and, starting next year, fine-tuning its benchmark rates.

Spain’s ample current account surplus should remain in place despite the higher cost of imports, especially of energy products, and the as-yet incomplete recovery in tourism. Spain’s net lending position, which includes the influx of transfers from Europe in addition to the current account balance, will present an even bigger surplus.

We are trimming our forecast for the public deficit, as the 2021 deficit came in considerably below our forecast thanks to growth in revenue from the various taxes that was higher than long-standing elasticities with respect to taxable income. Those elasticities are now expected to return to their usual levels and, on that basis, assuming no change to fiscal policy, we are forecasting a deficit of 5.7% of GDP in 2022 and of 4.8% in 2023. The face value of Spain’s public debt will, however, continue to increase, although expressed as a percentage of GDP, indebtedness will ease a little from 116.4% this year to 114.6% next year. Both the estimated deficit and borrowing levels are higher than the thresholds set down in the EU’s fiscal rules, which for the time being remain up in the air.

Inflation is the biggest risk

There is more downside than upside. The assumption that energy prices will begin to ease from the spring is subject to geopolitical factors, including the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the potential collapse of the gas market. The emergence of new variants of the coronavirus could exacerbate business restrictions, for example, in China where there are doubts about the protection offered by the vaccine, potentially sparking fresh supply chain disruption. Lastly, a wage price spiral looks unlikely but cannot be ruled out (second-round effects). If such a spiral were to materialise, it would hurt Spain’s competitiveness and send risk premiums higher.

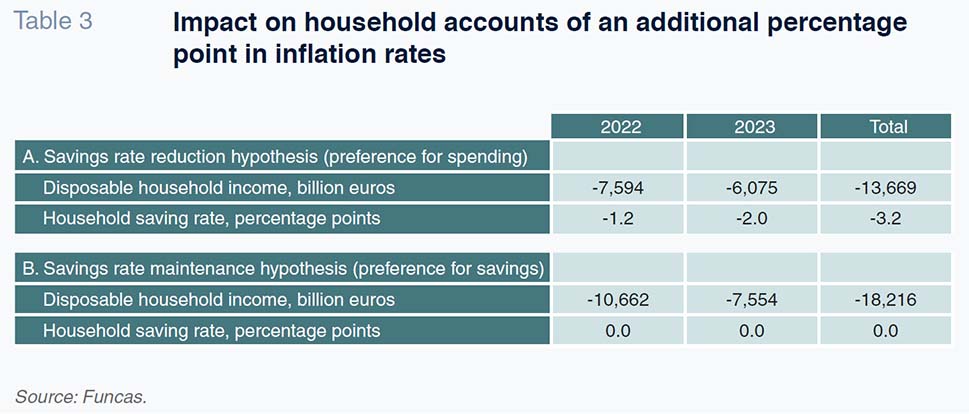

To illustrate the impact of inflation, we modelled a riskier scenario in which the CPI averages 4.7% in 2022 and 3% in 2023, i.e., one point higher than in the baseline scenario. Assuming wage moderation, the increase in the CPI would erode purchasing power (Table 3). The result would be a reduction in household disposable income over the two years by between 13.7 billion euros (assuming a drop in savings rates to maintain spending) and 18.2 billion euros (assuming spending is suppressed to keep savings rates in line with those assumed in the baseline scenario, affecting the economy and jobs, and thus household incomes).

Reactivation of the European fiscal rules from 2023, having been put on hold during the pandemic, poses another major challenge for the Spanish economy. It does not seem likely that the European authorities will reintroduce their deficit and debt ceilings abruptly in light of the scale of the imbalances prevailing in several member states, including Spain. Against that backdrop, a debate is underway in the EU about the options for reforming those rules. Although there are multiple possible scenarios, all signs suggest that budget policy will be subject to limitations of one kind or another in the years to come.

Raymond Torres and María Jesús Fernández. Funcas