Spain’s economic and fiscal outlook

GDP growth is expected to slow to 1.5% in 2024, down 0.9% from this year, although still significantly above the EU average, with inflation also expected to moderate further. Spain’s key source of vulnerability remains its fiscal imbalance at a time when sovereign borrowing costs are rising sharply, highlighting the need for growth-friendly fiscal consolidation.

Abstract:

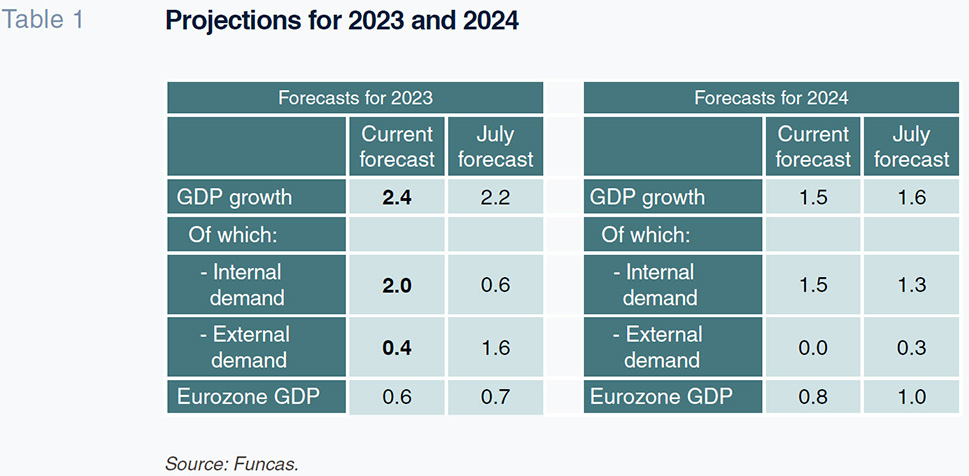

The forecast for GDP growth has been revised to 2.4% in 2023, up 0.2% from our projection in July, underpinned by the strong momentum at the start of the year, driven mainly by internal demand. Both public and private consumption have picked up strongly. However, a slowdown is underway and will become more palpable in the near future, due to the weaker external context, the exhaustion of household excess savings and the delayed impact of higher interest rates. Economic growth is projected at 1.5% in 2024, down 0.1 percentage points from our previous forecast. Yet, the favourable growth differential with respect to other EU countries would be maintained. The let-up in CPI should gain traction once the impact of the reversal of the current anti-inflationary measures has dissipated. Spain’s key source of vulnerability in the short- and medium-term is the country’s fiscal imbalance at a time when sovereign borrowing costs are rising sharply. Hence the importance of taking advantage of the opportunity afforded by the prevailing economic growth to embark on a roadmap for fiscal consolidation.

Economic slowdown and disinflation

The revision of Spain’s national accounts in September yielded noteworthy upward revisions of the provisional results for the last two years and revealed that Spain had actually revisited pre-pandemic GDP by the third quarter of 2022 (Fernández, 2023). According to the revised figures, internal demand was stronger than initially estimated, momentum that has carried over to this year, despite the slowing economy.

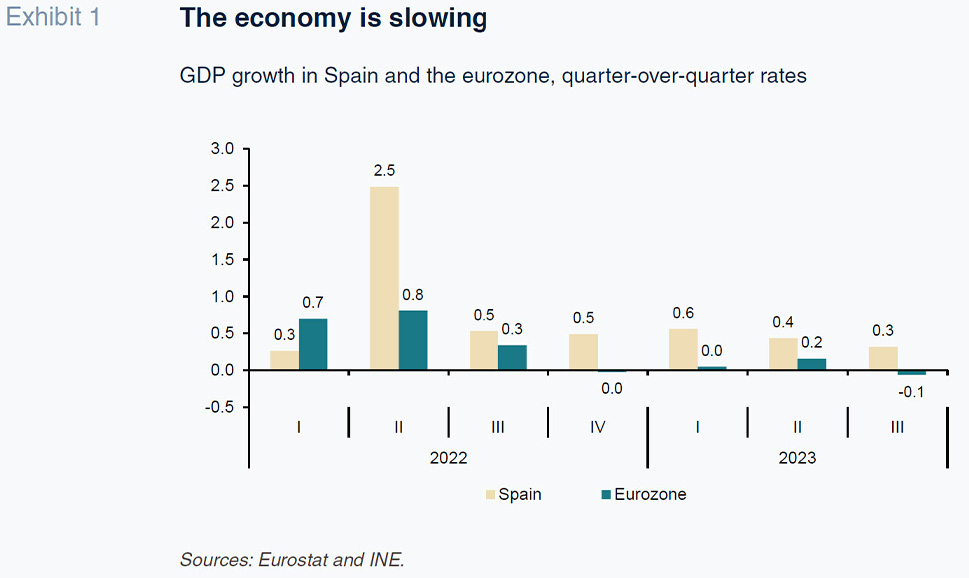

Having registered growth of 0.6% in the first quarter, Spanish GDP expanded a further 0.4% in the second quarter and by 0.3% in the third quarter, according to the provisional estimate. The slowdown is coming via trade as a result of the recession taking hold in much of the eurozone. Exports contracted in the second and third quarters, having notched up almost interrupted growth since the end of the health crisis. In contrast, internal demand has continued to hold up remarkably well. Private consumption and, to a lesser degree public consumption, stand out. Investment, however, has proven more volatile and has been slowing as the year has unfolded. At any rate, the Spanish economy continues to grow faster than the European average (Exhibit 1).

Employment, measured in hours worked as per the national accounts, increased by 1.5% in the second quarter, finally revisiting pre-pandemic levels, then slowed to 0.1% in the third quarter. Productivity per hour worked contracted in the second quarter and increased slightly in the third quarter, remaining above pre-pandemic levels at least, which, following the statistical revisions, were recovered in the second quarter of 2022. Growth in social security contributors accelerated in the second quarter but registered very low growth in the third. Overall, the labour market remains resilient, contrasting with the pattern observed during previous periods of economic weakness.

Job creation has propped up household disposable income, whose double-digit growth during the first part of the year (in nominal terms) is the highest in the historical series. The recovery in wage compensation, derived from collective bargaining negotiations and partial compensation for the loss of purchasing power of recent years, has also helped. On top of that, social benefits, notably pensions, have been restated for CPI.

In addition to boosting private consumption expenditure, the growth in disposable income has kept household savings rates above pre-pandemic levels. The growth in savings has in turn facilitated loan repayments, a phenomenon also being observed in the corporate sector. As a result, private sector debt has continued to come down, as it has been doing consistently since early 2021, following the pause induced by the health crisis. In the second quarter, the consolidated debt of Spain’s non-financial corporations was equivalent to 66.6% of its GDP while that of households stood at 49.9%, marking the lowest figures in the last 20 years.

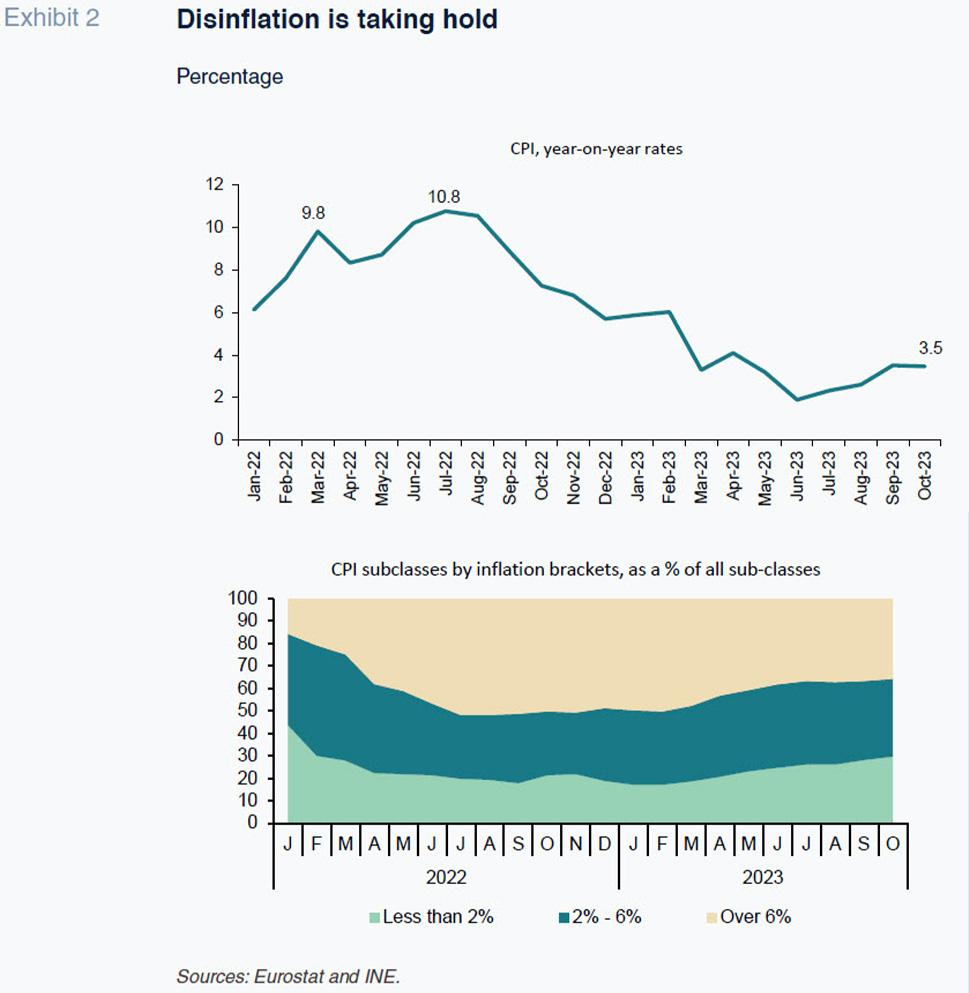

Disinflation is taking hold, albeit gradually and unevenly (Exhibit 2). CPI registered year-on-year growth of 3.5% in October. That is above the low recorded in June (1.9%) on account mainly of base effects, particularly around energy prices. Core inflation, meanwhile, continues to trend lower, from around 6% earlier this spring to 5.2% in October. Price moderation is spreading to most components of the price index. Of the 199 subclasses comprising the CPI, 100 presented inflation of over 6% at the start of this year, a figure that had fallen to 71 by October. In parallel, the number of components presenting inflation of under 2% increased from 34 at the start of the year to 59 in October.

Spain’s external surplus remains one of its strengths. The current account surplus hit a new record of 27.6 billion euros in the first eight months of the year. The goods trade deficit narrowed year-on-year, whereas the services trade surplus, in both tourism and non-tourism exports, registered strong growth.

Lastly, the public deficit came in at 32.88 billion euros in the first half of the year, compared to 34.86 billion euros in the same period of 2022. The improvement – very slim – is being driven by revenue, particularly receipts from new taxes, personal income tax and social security contributions. On the expenditure side, growth is high in intermediate consumption, wage compensation and social benefits, notably including pensions (with an estimated cost of €8.5 billion in 2023).

Projections for 2023-2024

The end of this year will be marked by a slowing economy as a result of the impact of higher interest rates, cooling across Europe (the growth forecasts for the eurozone have been trimmed) and, to a lesser degree, a slowdown in public consumption. The scant information available to date for the fourth quarter points in the direction of an economy losing steam. Industry looks the most vulnerable sector judging by the October PMI (well below the 50 mark indicating a contraction), while services are faring better (with a PMI of just over the 50 threshold, suggesting slight growth in activity). Growth in social security contributors slowed in October to below the monthly average for the third quarter and well below the spring figures.

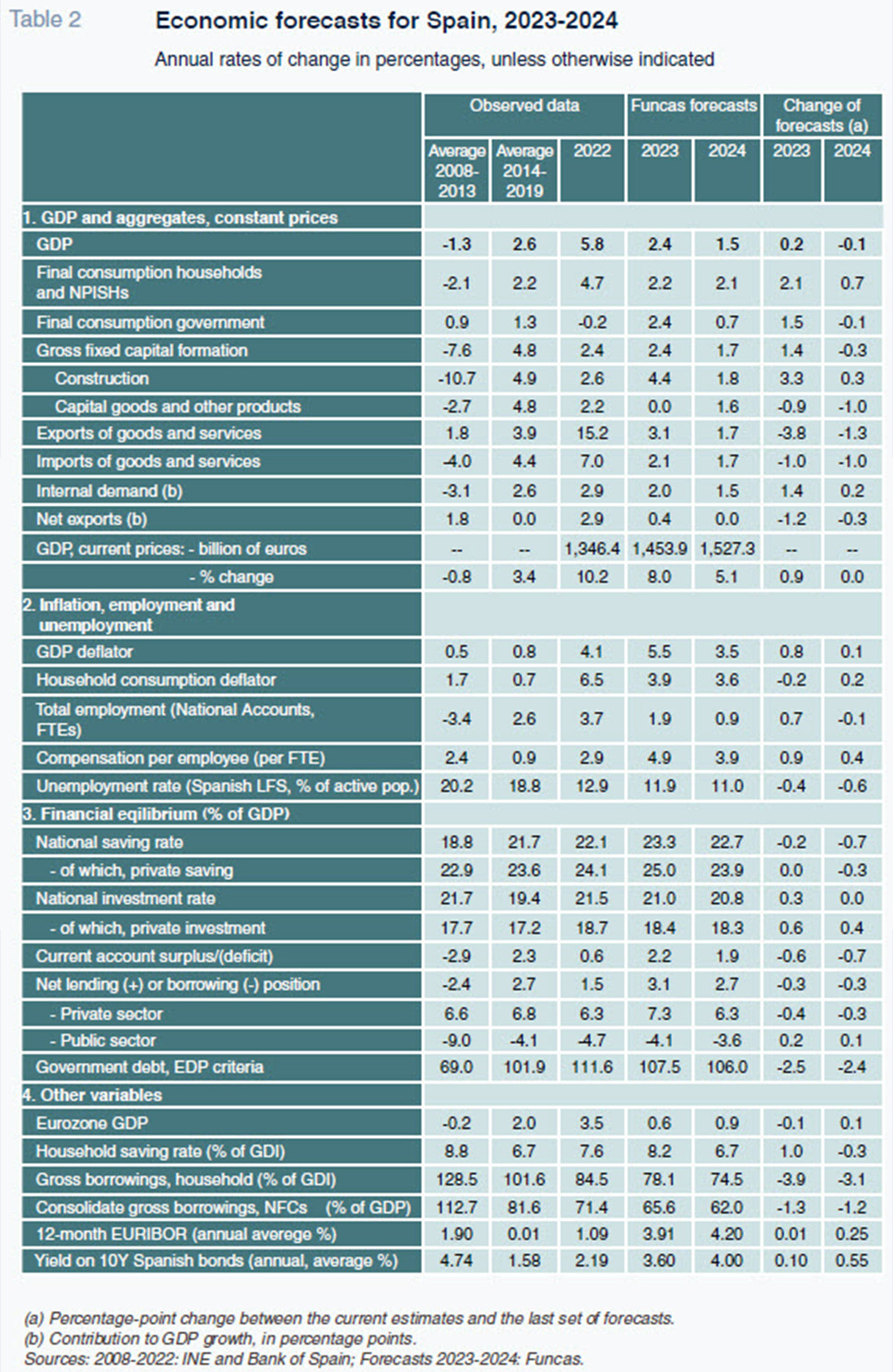

Nevertheless, growth for 2023 as a whole is forecast at 2.4%, up 0.2 points from our last forecast, thanks to the momentum at the start of the year (Table 1). That growth will be driven above all by internal demand. Domestic demand is being driven by a noteworthy rebound in both public and private spending, the latter facilitated by the growth in wages in real terms and labour market resilience (Table 2). Investment in construction is also evidencing the improvement in purchasing power. In contrast, investment in capital goods and other products, the component that is most sensitive to rising interest rates, is forecast virtually flat this year. Lastly, despite economic cooling across Spain’s trading partners, the external sector will still make a positive contribution to growth this year, thanks to full recovery of tourism in the wake of the health crisis and Spain’s strong competitive positioning in certain sectors, notably non-tourism services.

The economic slowdown is expected to become more palpable in 2024, due to the carryover effect from the end of this year, compounded by a loss of momentum in some of the factors currently propping up growth: the normalisation of tourism and the agreements for replenishing the purchasing power of wages, with their corollaries in terms of household disposable income and private consumption. Elsewhere, public consumption is also expected to make a smaller contribution in light of the upcoming reactivation of the fiscal rules. The Spanish economy is expected to grow by 1.5% in 2024, down 0.1 points from our last forecast. That growth will once again be driven by internal demand, with the contribution by the external sector forecast at zero. Nevertheless, that rate of growth would put Spain above the European average.

GDP growth is expected to gain traction as the year unfolds, underpinned by the outlook for monetary policy. We assume that the ECB will not increase official rates further, sticking instead with is new guidance that rates will be kept at higher levels for longer than initially expected. That scenario is consistent with the slight decrease in the deposit facility rate forecast for the second half of 2024.

Weakening demand should ease pressure on prices, albeit still gradually and unevenly, leaving inflation above the ECB’s targets for the entire projection period. The private consumption deflator is expected to come down slightly from 3.9% this year to 3.6% in 2024. Elsewhere, the GDP deflator, the best proxy for inflationary pressures, is forecast to drop from 5.5% this year to 3.5% next year. This forecast is based on prior episodes of disinflation, marked by asymmetric price adjustments (slower to come down than to go up) in the services sectors that are relatively sheltered from competition. In addition, energy prices have recovered, especially oil prices, following the decision taken by some OPEC members to pare back production. The worsening conflict in the Middle East and its possible reverberations in the region and for broader global geopolitics add an element of uncertainty that is already being felt in the form of volatile oil and gas prices.

The healthy trend in net exports of goods and services, coupled with an improvement in the real terms of trade thanks to cheaper imports, is expected to unlock a significant increase in the external surplus. The current account is expected to present a surplus of close to 2% of GDP throughout the projection horizon. The result in terms of the total external surplus, arrived at by adding European fund transfers to the current account surplus, looks even stronger.

In addition to the external surplus, the labour market should remain one of the main sources of economic resilience in Spain. The rate of unemployment is forecast at 10.5% in 2024, which would still be well above European average.

Fiscal imbalances, Spain’s biggest vulnerability

The succession of crises (health, energy, and war in Ukraine) has necessitated intervention by the various European governments in order to mitigate the impact on the most vulnerable sectors and preserve the productive fabric. As a result, the region’s public finances have deteriorated. The public deficit for the European Union as a whole topped 3% of GDP in 2022, compared to an almost-balanced budget prior to the pandemic. In Spain, the deficit has deteriorated by less than the European average but starting from a higher level, so that it reported a deficit of 4.7% of GDP in 2022. Only Italy, Romania, Hungary, and Malta present higher deficits. Public debt, meanwhile, is running at over 111% of GDP.

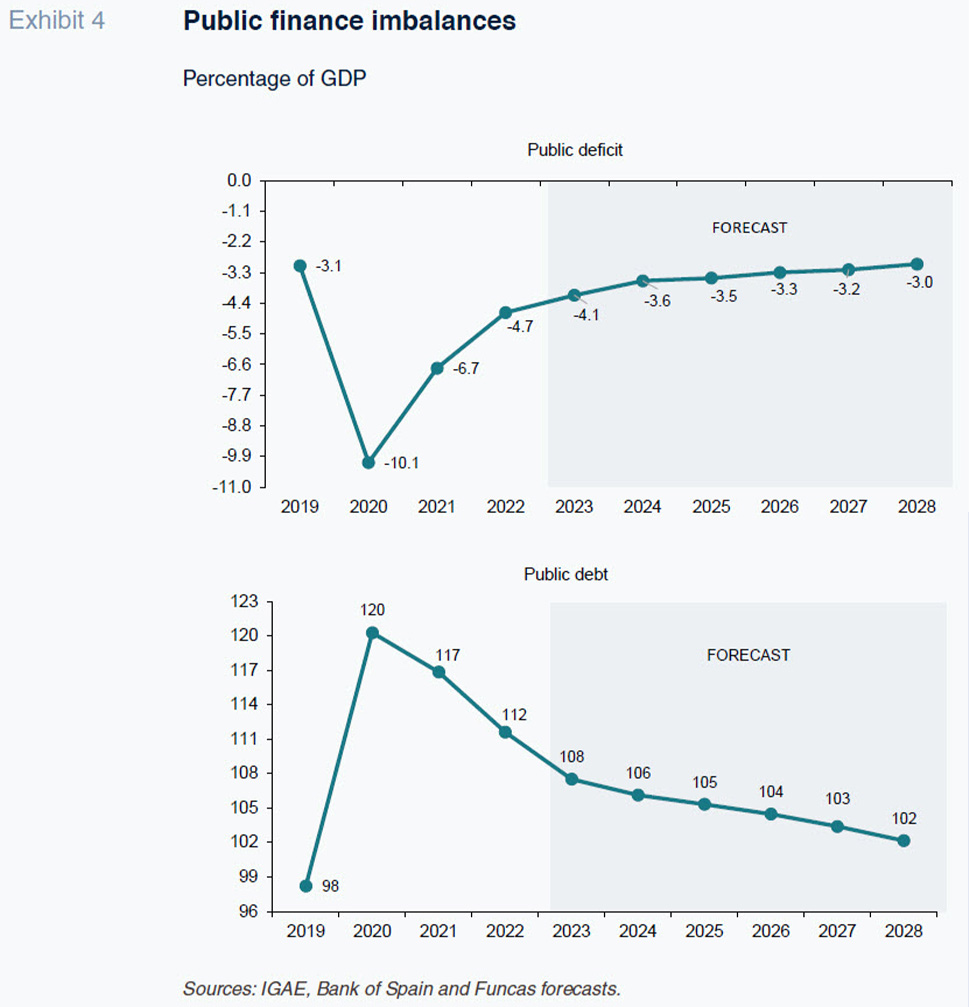

Looking forward, the economic slowdown, together with the anticipated increase in debt service costs on the back of higher interest rates, pose a public finance sustainability challenge. In the absence of deficit-cutting measures, we are estimating a deficit of 3.6% in 2024, with public debt at 106% of GDP, above pre-pandemic levels.

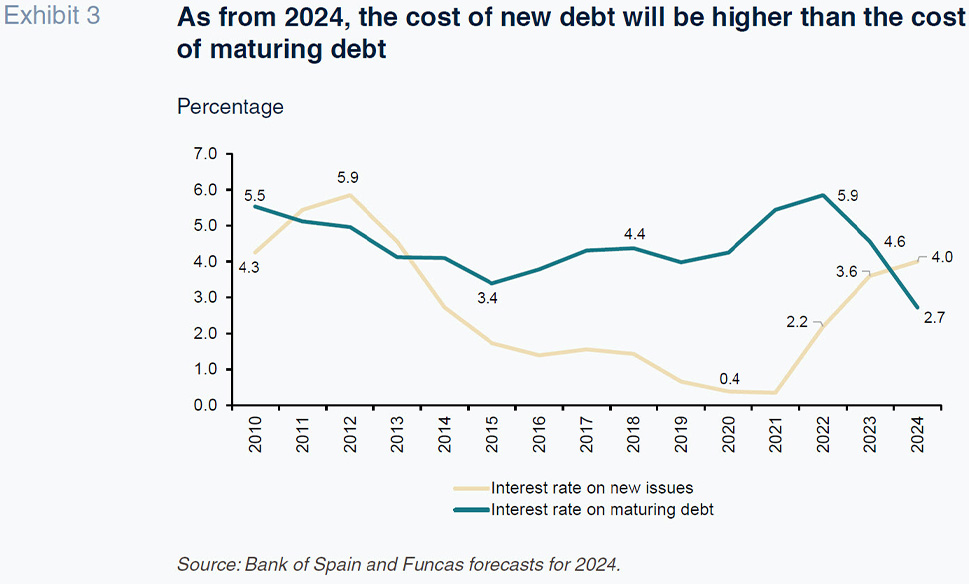

Over the medium– and longer-term, the persistence of a high public deficit is a source of vulnerability for the Spanish economy with the European fiscal rules about to come back into play and the ECB withdrawing support in the form of rates and debt repurchases (Torres, 2018; Torres and Sánchez, 2023). In addition, yields on 10-year bonds have risen from below 1% in recent years to around 4%, which, assuming status quo policy-wise, will increase the ratio of debt service payments over GDP. That is because, starting from the first quarter of 2024, the cost of newly issued debt will be higher than the cost of that being repaid. Therefore, in the absence of fiscal consolidation measures, there is no guarantee that leverage will follow a path that is compatible with the European rules.

Making relatively optimistic assumptions (GDP growth of 1.9%, inflation of 2% and interest rates of around 2.5%, framed by ‘normalised’ monetary policy), in the baseline scenario, the public deficit would not come down to 3% until 2028 (Exhibit 4). Public debt would remain above 100% that year. In other words, without specific measures, there would be no room for manoeuvre in fiscal policy in the event of new shocks in the next few years. Although the risk premium remains stable for now, in the event of turbulence in the financial markets, the situation could change drastically.

Risks

The Spanish economy has held up better than expected of late and could still give us a pleasant surprise in the coming months. Especially if the current sources of resilience (private sector deleveraging, international competitiveness, job creation) are compounded by a boon via the European funds.

There is still more downside than upside, however. In the near-term, intensifying geopolitical risks could unleash fresh disruption in the energy markets and in trade, triggering a stagflation shock. Faced with the risk of an interruption in the disinflation process, the ECB would be forced to tighten monetary policy further, doing away with the stability assumption underpinning these forecasts. A more pronounced increase in the cost of money than estimated in the baseline scenario would increase the risk of non-performance in the more vulnerable sectors and with it the risk of financial market turbulence. Overall, Spain’s greatest vulnerability lies with its public finance imbalances. Hence the importance of taking advantage of the opportunity afforded by the prevailing economic growth to embark on a roadmap for fiscal consolidation.

References

FERNÁNDEZ, M. J. (2023). Spain’s revised national accounting statistics: Positive and negative takeaways. SEFO, Vol. 12(6), November.

TORRES, R. (2018). Política fiscal europea: situación y perspectivas de reforma [European fiscal policy: Status and outlook for reform]. Información Comercial Española, July-August.

TORRES, R. and SANCHEZ, P. (2023). La economía europea tras el shock geopolítico. [The European economy in the wake of the geopolitical shock]. Papeles de Economía Española, 177.

Raymond Torres and Fernando Gómez Díaz. Funcas