Mortgage prepayment: An alternative to saving

After one year of intense interest rate increases, coupled with very slow pass-through to deposit rates, households have moved decisively to reconfigure their savings, and also their borrowings. In this process of recomposition of household financial flows and the search for an alternative to deposits, the early cancellation of debts, especially variable rate mortgages, which are undoubtedly the most affected by the rise in interest rates, has gained increasing significance.

Abstract: After 18 months of rate tightening, marked by an accumulated increase of over 4pp, the increases have by now been passed through to virtually all mortgages taken out at floating rates (two-thirds of the total stock of mortgages).That pass-through, which has been gradual but very consistent (in line with the contractually stipulated repricing schedules), contrasts with the slower pace of deposit repricing. Against this backdrop of high borrowing costs and relatively lower returns on savings, the prepayment of borrowings, especially those more affected by the rate increases, such as floating-rate mortgages, has emerged as a clear alternative to investing savings. Considering the long-run stability around monthly mortgage cancellations of approximately 26,000, we can infer that the incremental number of cancellations attributable to the increase in rates between June 2022 and June 2023 was around 6,000-7,000/month, which would put the cumulative number of mortgages prepaid during that period at somewhere between 75,000 and 85,000. As well, the weight of early redemptions can be estimated as ranging between 2-3% of the outstanding balance, representing approximately 9-14 billion euros. Indeed, these estimates suggest that early cancellations are in the order of magnitude of around half of the amount invested in Treasury bills and mutual funds in the first half of the year, which too are on the rise, thus underlining the increasing preferences of savers to reduce outstanding debts.

ECB rates, Euribor and pass-through to deposits and mortgages

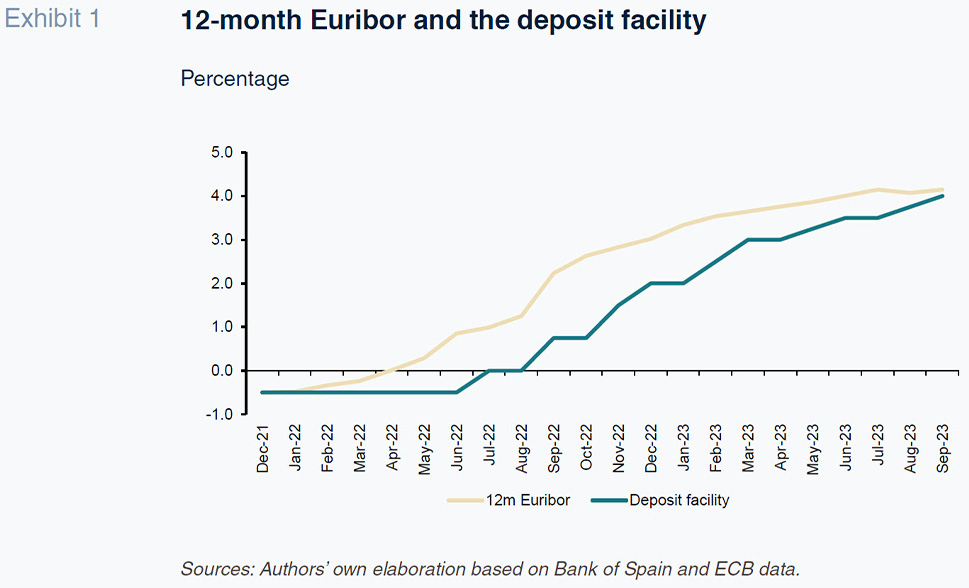

Since it first increased its benchmark rates in July 2022, the ECB has raised its rates 10 times, lifting the rate on its deposit facility (DF) from -0.5% to 4% at present. 12-month Euribor, meanwhile, which essentially discounts the average DF rate expected for the next 12 months, had begun its ascent six months before the ECB announced its first increase, undoubtedly anticipating it and those that followed. The convergence between the DF rate and 12-month Euribor and the stability displayed by the latter in recent months signal the belief that the ECB has reached, or is about to reach, its ceiling for official rates, albeit also signalling the expectation that rates will not be cut in the near future. The anticipated ceiling or landing rate in ECB rates could be left in place for a long spell – at least a year – judging by the trajectory being discounted by Euribor.

Compared to the trend in benchmark rates (Euribor and ECB-DF), the pass-through to the rates the banks offer their customers has been starkly different across the main asset and liability products. The rates demanded on new home mortgage loans have risen quicker on the back of the increases in benchmark rates, so that the beta factor, i.e., the ratio between the cumulative increase in the rates on new loans and that in benchmark rates, had reached 0.43 by the start of 2023 and 0.55 by mid-year.

In contrast, that same beta factor in the case of term deposits was a mere 0.16 at the start of the year but had climbed to 0.49 by mid-year. That acceleration, undoubtedly stimulated by growing competitive pressure as the expectation grew that rates would stay high for longer, has not shifted the perception that the new rate paradigm is being passed through to deposits much more slowly than to loans, particularly mortgages.

In fact, that beta factor of 0.55 observed on new mortgages would be even higher looking only at the rates applied to outstanding mortgages arranged at floating rates, which represent over two-thirds of the total. In floating-rate mortgages, as outlined in an earlier paper (Alberni, Berges and Rodríguez, 2022), interest rate repricing tends to take place annually, so that around one-twelfth of all outstanding loans get repriced monthly on the basis of the average Euribor during the previous month. Given the intense increase in Euribor already in the spring and summer of 2022 (Exhibit 1), a very significant percentage of floating-rate mortgages have already been largely repriced for the new environment and any left to do so will in all probability get repriced in the coming months, judging by the outlook for Euribor being discounted by longer-term market rates.

Response to the new rate environment: Lower demand for new mortgages and rise in cancellations of existing loans

Such a significant increase in mortgage rates, both new loans and already outstanding mortgages carrying floating rates, has necessarily had to have an adverse impact on demand for such loans, at a time when households’ disposable income is rising more slowly than the cost of money, so undermining their ability to service their mortgages.

That contraction in demand in response to the rate increases is particularly noticeable in new mortgages. Having registered growth of close to 20% year-on-year in 2021 and the first few months of 2022, the pace of growth started to slow throughout the second half of 2022, as new mortgage rates began to price in the rise in Euribor. However, it was clearly during the first half of 2023, when the beta climbed above 0.5, when demand began to contract sharply (by over 17%).

Much harder to observe, but probably more important in terms of its impact on the banking business, is how the households with mortgages at floating rates, which have seen their rates increase by 4 points (in many cases more than doubling their monthly mortgage payments), have reacted.

A first response was to renegotiate the terms with their lender banks, a possibility that arose with the Property Credit Agreement Act of March 2019. As a result, during the last two years, the number of mortgages whose rate has been amended as part of an agreement between lender and borrow has nearly doubled (to an annual average of 45,000), with most of the amendments consisting of a switch from floating to fixed rates according to statistics published by Spain’s statistics office, the INE.

Another logical response by households with floating-rate mortgages was to pay off some of their loans, drawing on savings whose remuneration was considerably lagging the pace at which mortgage rates were rising.

It is impossible to know exactly the scale of that response as the mortgage cancellation statistics also include mortgages that are cancelled at the originally scheduled maturity date. Nevertheless, insofar as those ‘natural’ cancellations tend to be fairly evenly paced over time, it is possible to analyse those statistical rhythms in order to infer outlying trends and examine whether they are correlated to the interest rates of relevance to mortgage costs.

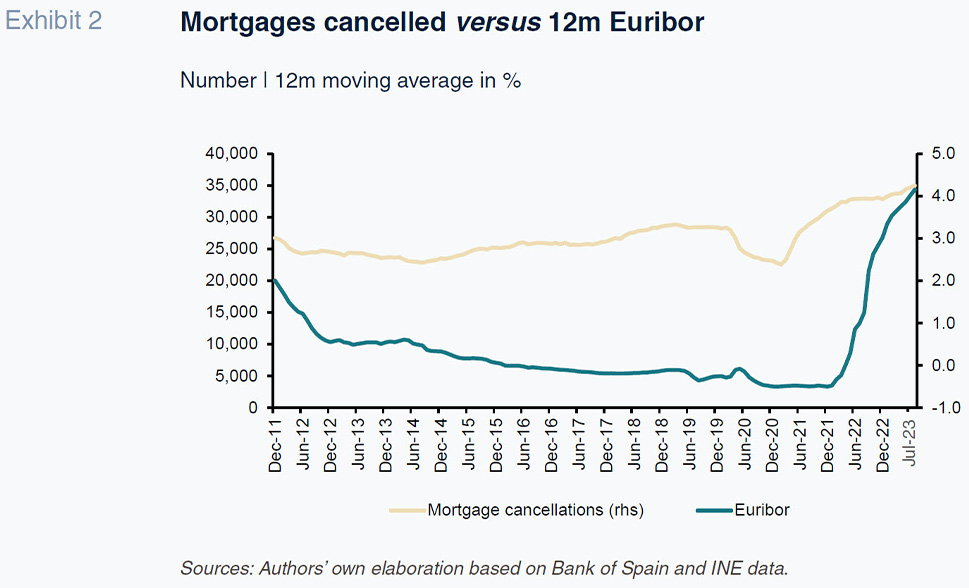

Exhibit 2 shows, going back a little over a decade, the historical series tracking the number of mortgages cancelled, expressed as a 12-month moving average in order to smooth out monthly swings. That series is charted alongside the trend in 12-month Euribor, the most important benchmark for the mortgage lending market.

The exhibit leaves little room for interpretation. Mortgage cancellations have been tended to be very stable, only changing during episodes related to movements in Euribor. Twice, when that benchmark rate fell (2012 and 2020), the number of cancellations decreased. To the contrary, the exhibit shows sharp acceleration in cancellations in parallel with the significant increase in Euribor etched out since early 2022.

On the basis of the aforementioned exhibit, considering the long-run stability around monthly cancellations of approximately 26,000, we can infer that the incremental number of cancellations attributable to the increase in rates between June 2022 and June 2023 was around 6,000-7,000/month,

[1] which would put the cumulative number of mortgages prepaid during that period at somewhere between 75,000 and 85,000.

As a complement to this behaviour of the number of write-offs, we have also analysed the series corresponding to outflows observed in the outstanding amount of mortgage credit. These outflows include cancellations, portfolio sales and transfers to write-offs, although what we are interested in measuring is whether there has been a jump in the series since the start of the rise in interest rates, and this is indeed the case. In the first half of 2023, these outflows relative to the outstanding balance are approximately one percentage point above the level of the previous year. Bearing in mind that the year 2022 already presented values above the average of the historical series, it is estimated that this weight of early redemptions can be found in a range between 2-3% of the outstanding balance, representing an amount of approximately 9 to 14 billion euros.

Mortgage cancellation rather than household savings

Based on the above estimates regarding the number of mortgages paid off on account of the new high-rate environment, we next sought to put those cancellations into context at a time when households are reconfiguring their financial savings for the new rate scenario, particularly the very different pace at which higher rates are being passed through to bank assets versus liabilities.

That rearrangement is proving very pronounced within bank deposits, the chief destination for household savings, at a little over one trillion euros. Households shifted a significant volume of their savings from sight to term deposits between June 2022 and June 2023 (the 12 months following the ECB’s first rate increase). Term deposits, the only product to offer higher remuneration, albeit very gradually and selectively so, have increased by close to 20 billion euros, marking growth of around 30% from the low level (65 billion euros) observed after nearly a decade offering zero remuneration. That increase in term deposits has been more than offset by the decrease in sight deposits, of over 30 billion euros, for a net decrease in aggregate household bank deposits since the ECB embarked on rate tightening of some 12 billion euros.

Having reduced the amount of savings held in deposits, Spain’s households have channelled their money into two main alternative products: investment funds and fixed income-securities purchased directly, particularly Treasury bills, in roughly equal amounts.

Fund investment is not new for Spanish households, with this product second only to bank deposits for two decades now. In fact, over the course of the last two decades, the two products have etched out a substitution pattern, which has become more pronounced in the last year, with funds receiving the bulk of household savings, specifically net subscriptions of around 15 billion euros during the period analysed. In support of this thesis that deposits are being funnelled into investment funds, note that it is the more risk-averse funds – fixed-income and targeted-return funds above all – that have received the biggest net contribution, with the riskier funds (equities) receiving zero or even negative net contributions. Also worth noting is the fact that the switch from deposits to funds does not, for the most part, imply the break-up of the bank-customer relationship but rather a product switch, as most of the fund managers are owned by banking groups.

What is new in household investing patterns is the significant direct purchase of fixed-income securities, particularly Treasury bills on the primary market, with individuals having purchased nearly 16 billion euros during the period under analysis, most of which in 2023.

Conclusion

After one year of intense rate increases, coupled with very slow pass-through to deposit rates, households have moved decisively to reconfigure their savings, and also their borrowings. On the savings side, they have reduced their overall deposits (and shifted from sight to term deposits), while sharply increasing their contributions to investment funds and, above all, their direct purchase of fixed-income securities, primarily Treasury bills via direct accounts with the Bank of Spain.

In this process of recomposition of household financial flows and the search for an alternative to deposits whose returns lag far behind market rates, the early cancellation of debts, especially variable rate mortgages, which are undoubtedly the most affected by the rise in interest rates, takes on a special role. Estimates based on the information available suggest that these early cancellations are in the order of magnitude of around half of the amount invested in Treasury bills and mutual funds in the first half of the year, thus underlining the traditional saying that “the best investment is to reduce debts... for those who can afford to do so”.

Notes

Cross-checking that analysis with a linear regression between the two variables yields similar conclusions, with the number of monthly mortgage cancellations increasing by around 1,500 for every percentage point increase in Euribor.

Referencias

Marta Alberni, Ángel Berges and María Rodríguez. Afi