EU fiscal rules reform and Spain’s fiscal position

After Spain’s public deficit initially soared to 10% of GDP and the public debt level rose to historical highs of 120% of GDP in the wake of the pandemic, reactivation of the economy and significant growth in tax revenue has since helped to underpin improvement in the county’s fiscal metrics. However, under a stricter EU fiscal framework, budgetary stability in Spain will face significant hurdles, unless further fiscal adjustments and reforms are implemented.

Abstract: Spain’s public finances deteriorated as a result of the pandemic, with the deficit soaring to 10% of GDP and public debt levels reaching historical highs of 120% of GDP. Since then, the reactivation of the economy and significant growth in tax revenue helped to underpin improvement in the country’s fiscal metrics; however, projections indicate Spain will record persistently high structural and overall deficits going forward unless further fiscal adjustments are implemented. As well, with the deactivation of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) escape clause in 2024, increased budget consolidation efforts will be needed in Spain. Meanwhile, the ongoing debate over the reform of EU fiscal rules is complicated by the divergent fiscal positions across EU countries as well as disparate views over the need for flexibility versus budget stability, resulting in increased challenges in reaching a consensus. In any event, under the anticipated stricter fiscal framework, fiscal consolidation in Spain will face significant hurdles, due to increased defence spending, investments designed to accelerate the energy and digital transitions, population ageing and climate change, which is expected to hit Spain particularly hard. Going forward, the EU should take a more active role in financing investments, while in parallel, Spain should accelerate progress on reforming the fiscal system, taking into consideration the particularities of the Spanish fiscal federalism framework.

Deficit and debt: Current situation and outlook

The pandemic made a huge hole in Spain’s public finances, particularly its deficit and debt. The country’s deficit hit 10% of gross domestic product (GDP), while public leverage marked its highest level in the last century: 120% of GDP (Lago Peñas, 2022). Since then, the country’s fiscal metrics have improved substantially. Reactivation of the economy had a very positive impact, while the extraordinary growth in tax revenue easily out-measured the budgetary cost of the actions put in place to mitigate the fallout from the invasion of Ukraine and the inflation crisis of 2022 and 2023.

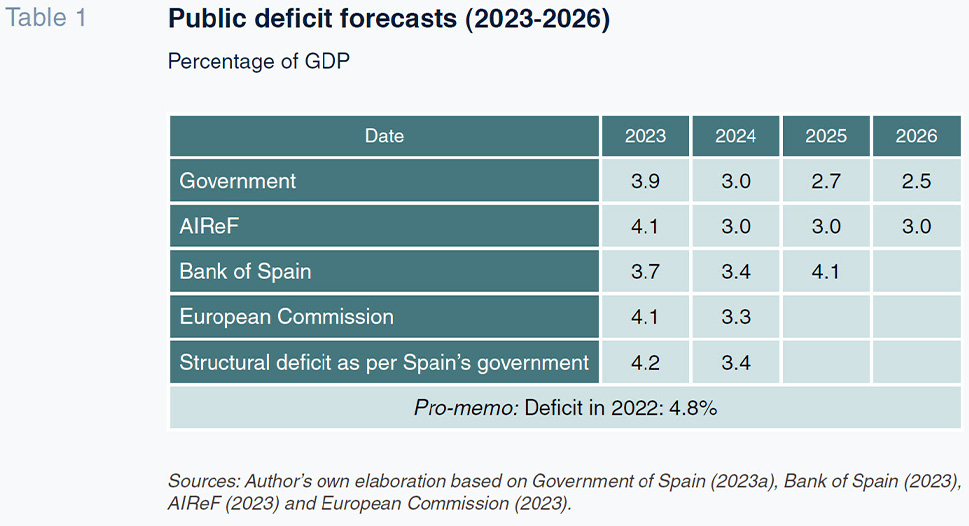

Nevertheless, the deficit is expected to come in at around 4% of GDP in 2023 (Table 1). A fiscal imbalance that is no longer attributable to the cyclical component. The government’s draft budget for 2024 estimates the structural component at 4.3% (Government of Spain, 2023b). The current projections for the coming years are none too encouraging either. Without additional adjustments, and assuming no change in spending or revenue policies, the structural and overall deficits will remain very high. Only the government believes the deficit will dip below 3% from 2025. Neither Spain’s independent fiscal authority, AIReF, nor the Bank of Spain contemplate such a favourable outcome in their latest projections.

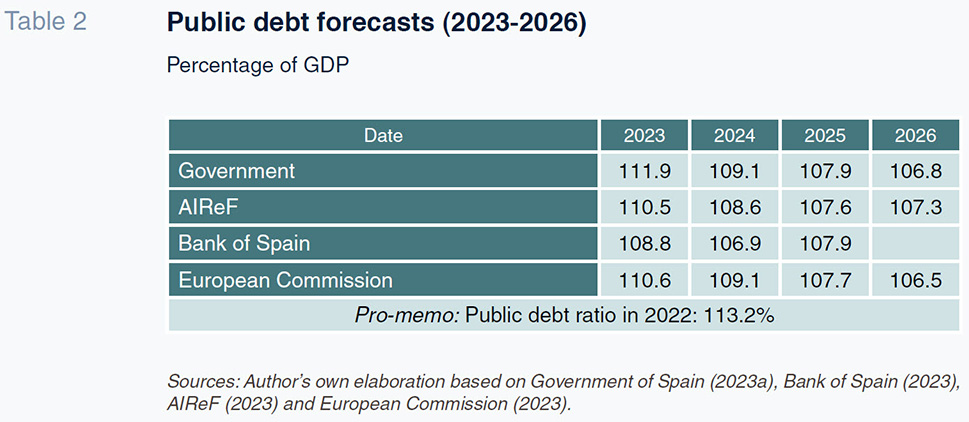

The deficit dynamics are mirrored in the debt dynamics. The improvement in the deficit and recovery in nominal GDP between 2021 and 2023 have driven the leverage ratio lower, albeit slowly. The projections compiled by the four institutions provided in Table 2 suggest that public borrowings will remain at over 105% of GDP in 2025 compared to 98% in 2019.

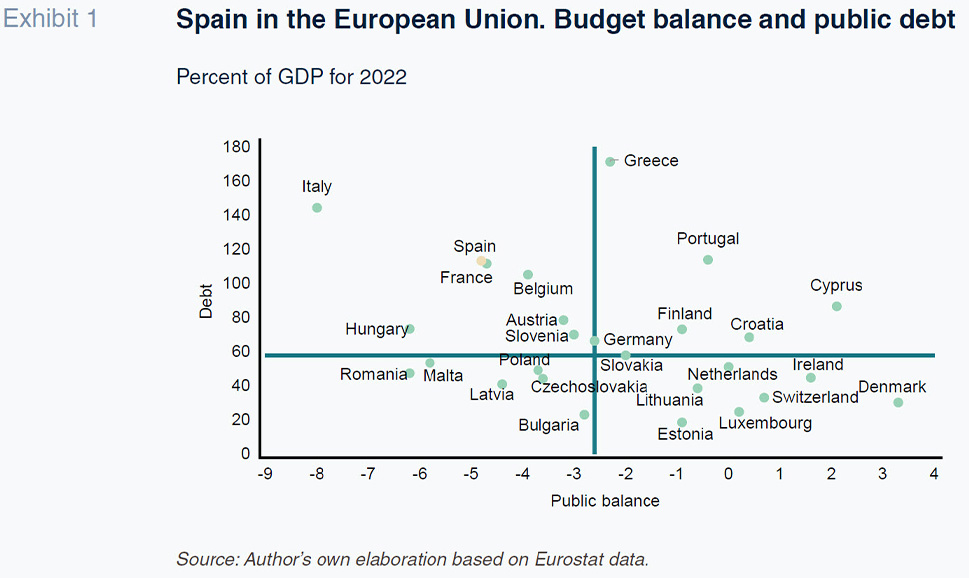

However, the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) escape clause will be deactivated in 2024, obliging Spain to step up its budget consolidation efforts. The scale of that effort has yet to be determined. That will depend on the final outcome of the fiscal rules reform currently in process. Although the process of revising them began before the pandemic, the events of the past four years in Europe have made the need for their overhaul more pressing. Indeed, Spain is not the only country whose fiscal metrics are far from the deficit (3% of GDP) and debt (60%) limits. Exhibit 1 shows how asymmetric the situation is across the EU-27. The straight lines depict the median deficit and debt readings. In other words, those corresponding to the EU-27 nations ranked fourteenth in terms of deficit (Germany) and debt (Slovakia). The countries with the healthiest public finances are located in the lower right-hand quadrant. Some have budget surpluses and debt levels of around 20% of GDP. The unhealthiest are grouped in the upper left-hand quadrant. Italy is the biggest concern, along with Greece, which has managed to cut its deficit after over a decade of cuts and bailouts (2010-2022), but whose debt ratio remains above 170%. Next in line come Spain, France, and Belgium, with Portugal in a similar situation in terms of debt but close to having a balanced budget. The exhibit goes a long way to explaining how the various countries have aligned around the fiscal rules reform, split between those looking for flexibility and those wanting to make sure that any such flexibility does not water down the budget stability framework. Fiscal adjustment beckons in the EU (Jones, 2023).

The fiscal rules reform process: Where does it stand?

At the time of writing, the negotiations around the new rules were at their final stages. The main EU authorities (European Council, European Commission, Eurogroup and Central European Bank) are keen to hammer out an agreement by the end of 2023. At present, the goal is to present drafts of the legal texts at the meeting of the EU’s Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) scheduled for 8 December. Failure to reach a consensus would generate uncertainty at a time of too much uncertainty in Europe. It would also create a conflict because the public finances of some of the member states make it very hard to apply the old rules unmodified.

We currently have three key sources of input for sketching out what the new framework might look like. The first source is the proposal presented by the European Commission one year ago (11 November 2022). Its essential six components are as follows (Lago Peñas, 2023a): Firstly, maintenance of the limits set down in the EU Treaty – a maximum deficit of 3% of GDP and a maximum debt ratio of 60% of GDP. Acknowledgement, however, that many member states are far from meeting those thresholds, especially the debt ceiling. To which end, it proposes an asymmetric approach. The countries that are close to meeting the thresholds should stick with them, whereas those that are far from them must commit to gradually converging towards them. Secondly, the key benchmark indicator would be the rate of growth in nationally financed net primary spending, excluding interest payments, expenditure on unemployment benefits and expenditure financed by discretionary measures or European funds. The structural deficit and the requirement to reduce debt by one-twentieth would no longer be relevant variables. The third key component is a multi-year approach with time horizons of up to seven years for government fiscal plans, to be evaluated using tools such as stress tests and stochastic analysis. Fourthly, the escape clauses would be left in place for tackling of symmetric and asymmetric shocks that only affect part of the European Union. Fifthly, the role of the national fiscal authorities would be reinforced around plan definition and supervision, but the European Commission would remain the key player. Lastly, the proposal entails revising the penalty regime, lowering financial penalties but making them more frequent and introducing reputational penalties.

The second source of insight is the legislative proposal presented on 26 April 2023, introducing some significant changes which, in general, tighten the rules. Firstly, countries with a deficit of over 3% of GDP would be required to reduce their deficits annually by an amount equivalent to 0.5% of GDP. Secondly, the debt/GDP ratio would have to come down significantly over the course of the national four-year plans. Thirdly, when the plans are extended to seven years, the bulk of the adjustments would take to place in the initial years. Fourthly, national net expenditure would have to be kept at all times below medium-term output growth. And fifthly: countries that deviate from their plans in the medium-term would by default come under the umbrella of an excessive deficit procedure.

The third source are the statements made by policymakers and leaks regarding positions on the reforms in the six months since presentation of the draft legislation. Three articles stand out. The first is the article published in several European dailies on 15 June by the German finance minister, Christian Lindner, which was signed by another 10 colleagues,

[1] emphasising the need to balance national accounts and reduce debt consistently over time, including having the most indebted nations reduce their debt ratios by at least 1% per annum. That article also came out against the notion that investment, no matter its destination, should be excluded from the calculations, asking whether allowing budget adjustment timeframes that run beyond the legislative cycle might encourage the systematic postponement of unpopular decisions.

The second piece is a leak, published on the Politico portal (2023) during the first week of October, of a four-page discussion paper for the ministers of finance outlining a “landing zone” for the reforms designed to reconcile positions. That document emphasises the idea that cuts should not be left until the end of the related timeframes; attempts to factor in Germany’s request for a minimum debt reduction metric; attempts to reconcile the classification of investments as expenditure with the need to pursue the twin green and digital transition and step up spending on defence; calls for more automated application of the rules and more power for the Council, as well as greater transparency and advisory powers for the European Fiscal Board; and, lastly, calls for reinforced and more transparent application of the excessive deficit procedures.

However, the ECOFIN meeting of 17 October ended without agreement and led to greater public airing of the differences between member states, our third piece of evidence. It has been made clear that France and Germany stand on different sides of the debate, to the extent that they, particularly France, have called for bilateral talks between the two countries in order to pave the way for an agreement, with Spain stepping up its multilateral work in parallel. In brief, the points for which there was still no consensus as of the start of November were the debt reduction guarantees and the exceptions applicable to certain investments. Germany continues to seek a minimum annual reduction in the debt ratio of one percentage point, limits on the deficit and the inclusion of all investments in the calculations, whereas France wants to focus on the long-term sustainability of public debt, while Italy wants exemptions on investments in defence and the investments financed via loans obtained under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF).

Outlook for Spanish fiscal policy in the near- and medium-term

Spain’s budget strategy for the coming years will have to be recalibrated for several reasons. Whatever the new fiscal framework in Europe looks like, it will have to acknowledge the need to cater to the current asymmetry in the member states’ fiscal parameters. However, it will also end up being stricter than the draft legislation presented in April and will force the member states to take steps to reduce their structural deficits. Secondly, it is clear Spain will have to tackle an increase in defence spending, shaped by international commitments, and in investments designed to accelerate the energy and digital transitions. Thirdly, population ageing will continue to exert pressure on spending on pensions, healthcare and social services, while climate change is expected to hit Spain particularly hard. According to the simulations performed by Gagliardi et al. (2022), Spain will be the most affected EU-27 member state. Elsewhere, the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2023) has estimated the budget cost for Spain of the policies needed to attain zero net emissions by the middle of this century. Adding the two vectors together yields a combined impact on the public debt ratio of between 8 and 9 percentage points of GDP by 2032.

In the face of this situation, we offer three thoughts. The first is that it is vital that the EU-27 play an active role in financing the hefty investments required, as it has done with those backed by the Next Generation EU funds. Spain stands to benefit especially from that support and so should be championing demands to reinforce the European architecture around this currently underdeveloped pillar. Complying with the fiscal rules and showing firm commitment to fiscal stability would legitimise such a leadership role.

Secondly, the reforms under debate should be nailed down urgently in order to optimise a fiscal system which necessarily needs to be articulated around budget rebalancing. However, it is just as pressing to reinforce the institutional and organisational framework so as to allow widespread and rigorous public spending assessments on which to substantiate adjustments and reallocation. The generic and indiscriminate cuts applied during the last decade need to be avoided and replaced by precision.

Lastly, the national stability framework needs to be fine-tuned intelligently, taking into consideration its current limitations and acknowledging the fact that Spain’s regional governments have budgetary roles of a significance only found elsewhere in the EU-27 in Germany’s Länder. Such changes need to go hand in hand with modifications to the regional financing system and be accompanied by structural solutions to the existing extraordinary financing mechanisms (Lago-Peñas, 2023b).

Notes

References

AIReF. (2023). Report on the 2023-2026 Stability Programme Update, 11 May 2023.

https://www.airef.es BANK OF SPAIN. (2023).

Macroeconomic projections for the Spanish economy (2023-2025), 19 October 2023.

https://www.bde.es EUROPEAN COMMISSION. (2023). 2023 Country Report - Spain.

Institutional Paper, 233, 14 June 2023.

https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/ GAGLIARDI, N., ARÉVALO, P. and PAMIES, S. (2022). The Fiscal Impact of Extreme Weather and Climate Events: Evidence for EU Countries.

Discussion Paper, 186. European Commission.

GOVERNMENT OF SPAIN. (2023a). Stability Programme Update, 2023 - 2026. 31 March 2023.

https://www.hacienda.gob.es GOVERNMENT OF SPAIN. (2023b). Draft Budgetary Plan for 2024. 15 October 2023

https://www.hacienda.gob.es IMF. (2023). Fiscal Monitor: Climate Crossroads: Fiscal Policies in a Warming World. October 2023.

https://www.imf.org JONES, E. (2023). The coming fiscal adjustment in Europe.

SEFO, Vol. 12, No. 5.

LAGO-PEÑAS, S. (2022). Las cuentas públicas de la pandemia: balance y perspectivas. [Public finances during the pandemic: Assessment and outlook].

Papeles de Economía Española, 173.

LAGO-PEÑAS, S. (2023a). Spanish Fiscal Policy in an EU Context: The Transition Back to Normal.

SEFO, Vol. 12, No. 4.

LAGO-PEÑAS, S. (2023b). Las reglas fiscales europeas y su plasmación en las haciendas subcentrales españolas [The European fiscal rules and how they affect Spain’s sub-central finances].

Papeles de Economía Española, 175.

POLITICO. (2023). Economic Governance Reform Landing Zone. Draft, 6 October 2023.

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics at University of Vigo and Senior Researcher at Funcas