Monetary policy 2023 and interest rate increases: Outlook and impact

The monetary policy roadmap for 2023 will continue to prioritize the fight against inflation, with successive official rate increases at least for much of the year, although accompanied by a slower increase in EURIBOR. Within this context, the banks will continue to play a key role in credit provision to the economy, yet while they could face improved income prospects, notable challenges exist within the prevailing uncertain climate.

Abstract: In 2023, the effort to fight inflation will go beyond the battle for economic and financial stability, with the institutional credibility of monetary policy itself in play. The roadmap looks set, marked by successive official rate increases for at least much of the year. Pricing in monetary policy changes, EURIBOR has traded significantly higher since July 2022. That said, the average rates effectively applied by the Spanish banks have increased more gradually. After initial sharp upward movements, the benchmark rate appears to have largely discounted the monetary policy shift and the outlook for further official rate hikes, so that it should sustain lower growth in 2023. Within this context, just as the banks have played a crucial role in providing credit during the pandemic, they will remain key in the prevailing uncertain climate. It is important, however, to consider their situation from a broader perspective. Several recent studies by supervisory bodies suggest that, although the banks’ income could increase on the back of higher rates, they face a number of challenges, some bigger than others, including higher funding costs, shrinking lending volumes and an uptick in non-performance due to economic weakness.

Introduction: Latest decisions and what could be next

Monetary policy faces major challenges in 2023. The eurozone is set to increase in size: Croatia will become the twentieth country to use the single currency. However, that looks like a small challenge by comparison with others, specifically the effort to tame inflation, which will go beyond a battle for economic and financial stability, testing the institutional credibility of monetary policy itself. Although the roadmap looks set, 2023 will be marked by numerous uncertainties. On December 15th, 2022, the ECB’s Governing Council decided to increase its three official interest rates by 50 basis points and, more importantly, underlined that: “based on the substantial upward revision to the inflation outlook, [it] expects to raise them further. In particular, the Governing Council judges that interest rates will still have to rise significantly at a steady pace to reach levels that are sufficiently restrictive to ensure a timely return of inflation to the 2% medium-term target.”

The ECB trusts that keeping interest rates at restrictive levels will reduce inflation by dampening demand, while guarding against the risk of a persistent upward shift in inflation expectations. It continues to insist, however, that it is taking a contingent approach given the level of uncertainty and the component of the increase in prices that does not depend specifically on its actions (mainly, energy prices). Clearly, the trend in prices in the eurozone has sustained a quantitative and qualitative step change in recent months, one that has been particularly pronounced in certain countries, including Spain. As the Bank of Spain noted in its Economic Bulletin for the first quarter of 2023, which talks about the crossover of the inflationary phenomenon from energy to the other index components, inflation started to spike in Spain in December 2020. The initial uptick was limited to energy prices but later spread to food and the other components of consumer price inflation. The Bank of Spain’s report underlines the importance of understanding the extent to which that generalisation of inflation is attributable to the increase in energy prices, stressing that the increase in inflation is partly due to the bigger scale of the recent shocks but also more intense transmission of movements in energy prices to all other consumer prices.

It therefore no longer makes sense to talk about cost inflation but rather a widespread – and somewhat ‘sticky’ – increase in the prices of nearly every item in the consumer basket. The ECB expects to be able to control that phenomenon. It notes in the policy statement outlining its outlook in conjunction with the decisions taken on December 15th that although monetary policy tightening is making business and household borrowing increasingly expensive, “bank lending to firms remains robust, as firms replace bonds with bank loans and use credit to finance the higher costs of production and investment”. However, “households are borrowing less, because of tighter credit standards, rising interest rates, worsening prospects for the housing market and lower consumer confidence.”

In this paper, we look back at the trend in the key monetary policy tool for curbing inflation – interest rate hikes – and the potential impacts for the banks and their activity, along with the outlook for interest rates in 2023. Note that the ECB’s strategy includes reviewing the connection between its monetary policy and financial stability. The last such review took place in December 2022 and revealed a deterioration in financial stability, a development primarily attributed to economic weakening and the attendant increase in credit risk. It is also worth keeping an eye on sovereign debt vulnerabilities in a context of increasing issuance and borrowing costs. Nevertheless, the ECB acknowledged in its monetary policy statement of December 15th that the “euro area banks have comfortable levels of capital, which helps to reduce the side effects of tighter monetary policy on financial stability.”

Outlook for interest rates

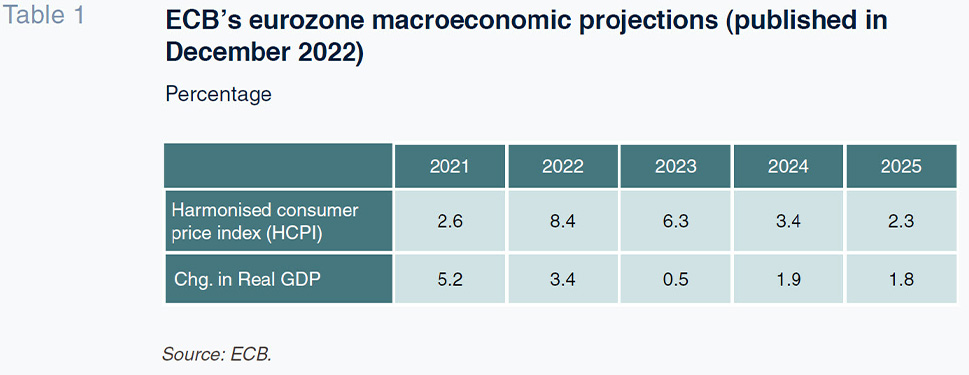

Table 1 provides the ECB’s macroeconomic projections for the eurozone as of December 2022. They show that the monetary authority does not expect inflation to approach its target of 2% until 2025. It is therefore targeting a path of gradual adjustment and the projections themselves are tantamount to explicit acknowledgement of the difficulty in reining in inflation over a short period of time, as shown by the empirical evidence. As for GDP, 2023 is expected to a be a year of transition marked by meagre growth of around 0.5%, followed by stronger yet moderate growth of under 2% in 2024 and 2025.

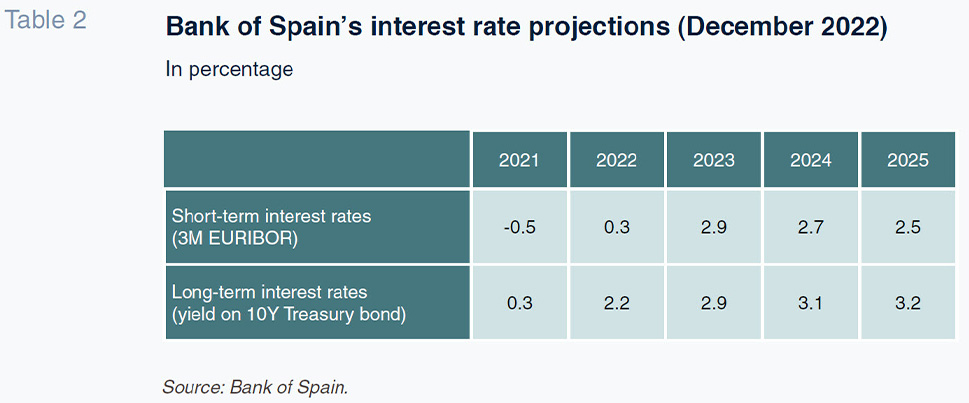

Table 2 provides the Bank of Spain’s interest rates projections, likewise published in December. Two key observations. Firstly, short-term interest rates are expected to continue to increase until 2024 and long-term rates, until 2025. Secondly, and relatedly, short- and long-term rates are expected to cross over this year, foreshadowing yield curve flattening and significant perceived uncertainty around 2023.

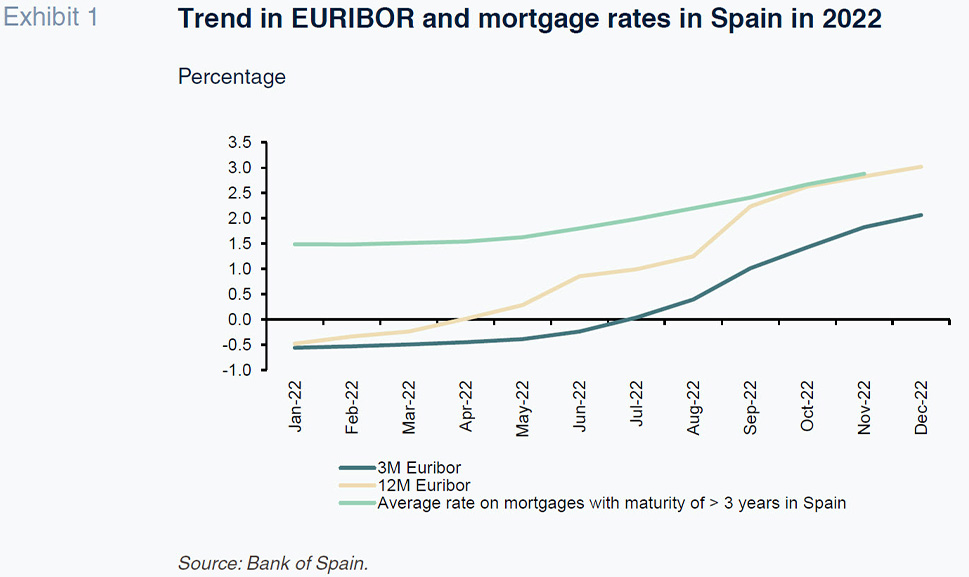

The monthly trend in interest rates in 2022 is shown in Exhibit 1. It is important to underline the fact that inflation remains subdued by historical standards. However, the recent run-up has been intense and taken place over a relatively short period of time. Short- and long-term rates (using 3- and 12-month EURIBOR as proxies, respectively) have risen sharply since July 2022. The average rates effectively applied by the Spanish banks have increased more gradually, however, and remained at 2.8% as of November 2022 (last figure available). Exhibit 1 also reveals how EURIBOR has anticipated the changes in monetary policy and, following the initial sharp increases, currently appears to have digested most of the expected remaining official rate increases.

The role of banks: The need for perspective

Just as the banks played a crucial role in providing credit during the pandemic, they remain key in the prevailing uncertain climate. However, it is important to put the situation in perspective. It would be mistaken to already claim victory for the banks in the wake of the recent rate increases. Indeed, they are part of the financial normalisation process that implies being able to charge for lending and remunerate savings, which had been largely lost while rates were in negative territory. However, the looming period of scant growth and fears of recession spells numerous risks for the banks and warrants prudence. For further insight, it is worth taking a look at the paper published by Luis de Guindos (Vice-President of the ECB) and Andrea Enria (Chair of the ECB’s Supervisory Board) on the monetary authority’s blog on December 20th, 2022, under the heading, “Are banks ready to weather rising interest rates?” Their analysis gauges bank resilience to interest rate shocks under two different macroeconomic scenarios. In the first, yield curve flattening, specifically a 300bp increase in short-term rates and a 100bp increase in 10-year long-term rates. That is what they describe as a “scenario consistent with the need to bring down inflation more decisively in the short-term, and an expectation of success in the medium-term.” Their second scenario contemplates a steepening of the yield curve, specifically an increase of 100 basis points in the short-term rate and an increase of 300 basis points in the long-term rate. That scenario is “consistent with a fast decrease in inflation, accompanied by medium-term concerns about the world economy.”

The results suggest that the European banks are well prepared for a variety of interest rate shocks and should see growth in net interest income; however, in the curve flattening scenario in particular, certain banks would face a significant increase in their funding costs that would be even larger than the projected increase in their earnings. The banks could also face higher credit losses as firms and households could struggle to service their debts in an environment of rising rates. Asset quality deterioration could require higher provisions, and would have a negative impact on banks’ capital, particularly under the sharp steepening scenario.

It is similarly interesting to analyse some of the data and observations provided by the Bank of Spain in its last Financial Stability Report (Autumn 2022), which are very much in line with the ECB’s analysis. That report notes that “were the macroeconomic risks [....] to materialise, the adverse impact on banks’ profitability and solvency could be significant. Rising interest rates will foreseeably boost banks’ income, but they will also put upward pressure on their funding costs. In particular, the pass-through of higher market rates to the cost of deposits may increase going forward. Moreover, higher borrowing costs for households and firms, together with a drop in their real income owing to higher inflation, will reduce their ability to pay, which in turn could trigger a significant increase in impairment provision costs.”

The Bank of Spain considers that its stress tests reflect high aggregate resilience in the banking sector to “an adverse scenario of materialisation of macro-financial risks, even though this would entail a certain degree of capital charge...”.

Even though loan non-performance in Spain remains below 4%, there are still carryover effects from the pandemic. The Bank of Spain notes that in the business sectors most affected by the pandemic (which accounted for 17.9% of total credit extended to non-financial corporations as of June 2022), non-performance has continued to rise, albeit slowly, to 6.1%. Although non-performance in Stage-2 and forborne loans decreased during the first half of 2022 (latest information available), that segment’s NPL ratio still stood at 7.2% as of June.

Lastly, the economic environment could affect the volume of credit and not just its cost. The Bank of Spain itself maintains that “net interest income is also expected to grow in Spain in the coming quarters as a result of the repricing of variable rate loans (and new lending at higher rates) due to the increase in the EURIBOR in recent months. However, this growth may be partially offset by a fall in volumes in the event of an economic slowdown.”

Conclusions

In sum, 2023 is set to be a year of adaptation, not exempt from risk, with rates continuing to rise, for at least the first half, albeit with market rates (EURIBOR) requiring smaller adjustments for official price-of-money expectations. Broadly speaking, we can highlight four major challenges:

- Credibility: The monetary authorities are trying to anchor private agents’ inflation expectations so that they factor the prevailing inflation problems into their spending and financing decisions and, thereby, correct them. If inflation persists, it will be extremely hard for the monetary authorities to preserve their credibility.

- Related to the credibility challenge, the central banks will strive to make their transmission mechanism work. That implies keeping growth in credit at moderate levels, something the most recent figures for 2022 appear to be beginning to confirm.

- Elsewhere, and despite not being relevant to this paper, it is worth noting the European fiscal coordination challenge. If the region’s monetary measures are contractionary while its fiscal measures are overly lax, widespread and insufficiently targeted, the battle to control inflation and attain monetary normalisation will be harder.

- Lastly, there are exogenous constraints. The effects of the war in Ukraine will continue to reverberate, as will the uptick in the pandemic in China. In general, anything that affects provisioning mechanisms and the cost of energy will continue to pose a serious risk in 2023.

Santiago Carbó Valverde. University of Valencia and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas