Managing the risks of quantitative tightening in the euro area

Recent quantitative tightening decisions undertaken by the ECB are important to reduce surplus liquidity and improve the functioning of the monetary transmission mechanism in the euro area. Nevertheless, they pose important risks for commercial banks, central banks, government finances, and the ECB itself.

Abstract: The Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) agreed on October 27th, 2022, to encourage early repayment of loans given out to banks through targeted long-term refinancing operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. On December 15th, the Governing Council announced that it would slow down the reinvestment of the maturing principal on assets held within the large-scale asset purchase programme to shrink those holdings by roughly €15 billion per month starting in March 2023. These two decisions are important to reduce surplus liquidity in the euro area and to improve the functioning of the ECB’s monetary transmission mechanism. Nevertheless, they pose important risks for commercial banks, central banks, government finances, and the ECB itself. Managing those risks will progressively dominate concerns in the Governing Council as the pace of interest rate rises that started in July 2022 begins to slow in the second quarter of 2023.

Introduction

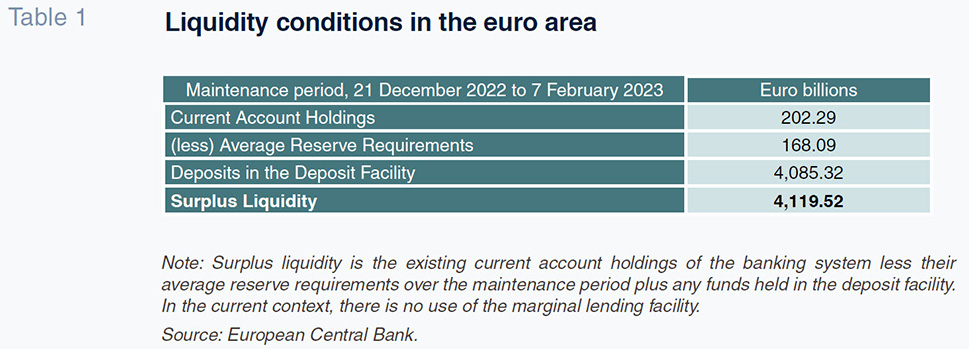

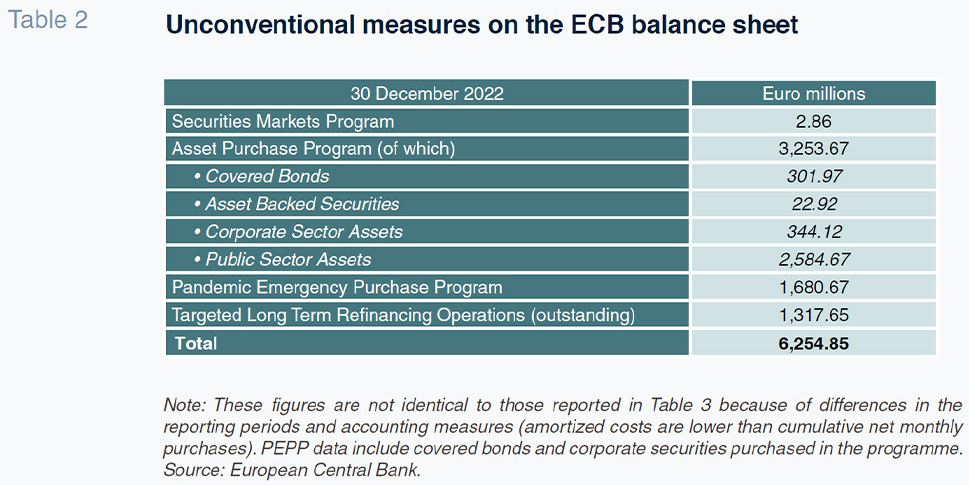

The Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) began raising interest rates in July 2022. By December of that year, the main policy rates had increased by 250 basis points, or 2.5 percent, taking the deposit rate paid on deposits held at the central banks that make up the euro area (the Eurosystem) from negative 0.50 percent to positive 2.0 percent in just six months. Along the way, monetary policy makers noted that they need to match this increase in policy rates with a reduction of other accommodative measures to strengthen the impact of policy changes on credit conditions in the economy and to reduce the volume of surplus liquidity in the European banking system. [1] By end December, the ECB estimated that the euro area contained approximately €4 trillion in surplus liquidity (Table 1). This surplus liquidity existed as a result of the more than €6 trillion expansion in the Eurosystem’s cumulative balance sheet since 2010 through a combination of asset purchase programmes and long-term refinancing operations (Table 2).

Therefore, on October 27th, the Governing Council decided to change the terms on loans given to commercial banks during the pandemic through targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) to encourage early repayment. The Governing Council followed with another decision on December 15th to slow down the reinvestment of the maturing principal of asset holdings accumulated through its large-scale asset purchase programme.

The purpose of this second decision is to begin shrinking the collective balance sheet of the Eurosystem by roughly €15 billion per month starting in March 2023. Moreover, ECB President Christine Lagarde emphasized in her December monetary press conference, this shrinkage of the Eurosystem balance sheet is not a substitute for further increases in the ECB’s policy rates, but rather “to complement” or “to align with” interest rate rises as “the primary tool to fight inflation”. Therefore, Lagarde announced that there would be a series of further interest rate adjustments to run alongside the early repayment of the TLTROs and the slowdown of reinvestment on the asset purchase programme. [2]

Lagarde also noted that there were significant risks associated with the process of balance sheet reduction or quantitative tightening (QT). “The reduction of the balance sheet – QT – is a new experience for us,” she observed.

[3] And while she did not go through the risks in detail either in her opening statement or in her response to questions, it is clear that those risks apply to commercial banks, central banks, government finances, and the ECB itself.

Lagarde explained that the Governing Council would agree the operational details for implementing quantitative tightening in February 2023 and that they would “continuously assess the impact this measure is having on financing conditions, on the monetary situation, and on the monetary policy stance” looking ahead.

[4] By implication, managing the risks associated with balance sheet reduction efforts are likely to predominate concerns within the Governing Council as the pace of interest rate increases starts to slow and the cumulative withdrawal of surplus liquidity rises. Those risks exist for commercial banks, central banks, government finances, and the ECB itself. Given that more than half of the €1.3 trillion in outstanding TLTROs will mature by June 2023, that shift in attention could happen before the end of the second quarter.

Banks and central banks

The decision to reduce the balance sheet of the Eurosystem brings opportunities and risks for commercial banks (including other monetary financial institutions) and central banks in the euro area. The opportunities centre on the strengthening of interbank lending markets and the release of collateral for securitized lending. The introduction of large-scale asset purchases in 2015 and the dramatic expansion of the large-scale asset purchase programme at the onset of the pandemic has removed a significant amount of high-quality liquid assets from the market that could otherwise be used as collateral for securitized borrowing. So have the collateral requirements for banks to access long-term refinancing operations, including the third round of TLTROs announced shortly before the start of the pandemic in September 2019. As a result, commercial banks have relied on their own liquidity to meet regulatory requirements for liquidity maintenance and for “own funds and eligible liabilities” (MREL) – and the redistribution of central bank liquidity among banks in the euro area has declined. [5]

By encouraging the banks to pay back the money they received through TLTRO III, the ECB will both reduce the volume of central bank liquidity and release the collateral held against those loans back into the market. This should make it easier and more attractive for banks to redistribute liquidity in both unsecured and collateralized interbank lending markets. Indeed, as Nicou Asgari and Martin Arnold reported in the

Financial Times on the eve of the October 27

th Governing Council decision, that is the goal.

[6] That reporting rested on the findings of an International Capital Market Association

Repo Market Survey conducted in June and published in October. Banks were complaining about the collateral shortage before the ECB started increasing interest rates: “the securities most in demand were German, French, and Italian government securities.”

[7] Many of those same banks indicated that they would face few challenges if the ECB were to wind up the TLTRO programme early.

[8]

Few if any of those banks foresaw the speed with which the Governing Council would increase interest rates or the pressure that would place on government bond prices. The widespread expectation in early July was that the Governing Council’s first move would be only 25 basis points, or 0.25 percent. Instead, the Governing Council surprised the markets with a rate increase that was twice as large and followed that with rises of 75 basis points in September and October, plus a fourth increase of 50 basis points in December. The effect of these rate rises has been to lower the value of the collateral that will be returned to the markets. This is true particularly for the assets used to acquire TLTRO funds under relaxed collateral requirements – with important implications for the cost of funds available to the smaller Italian banks, for example. [9]

The cumulative shrinkage of assets held within the asset purchase programme will only add to this pressure. That slowdown in the reinvestment of maturing principle will reduce demand for government bonds and so leave greater supply for use as collateral. But it will also put downward pressure on bond prices and therefore the mark-to-market value of bank assets and so indirectly put upward pressure on the cost of funding for those banks most affected. This downside risk will be greatest for those banks that relied most heavily on their TLTRO loans to meet regulatory liquidity requirements. This explains why the actual early repayment of TLTROs has undershot market estimates since the Governing Council’s October 2022 policy announcement. [10] Despite the fact that the terms on the loans are less attractive now, many banks are holding onto that liquidity so long as they can. It also explains why those European banks that can access the market are seeking to issue bonds before interest rates go up further. [11]

The opportunity for central banks is that a strengthening of interbank lending markets will strengthen the transmission of monetary policy. The risk is that the transition for banks from relying on their own liquidity to meet regulatory requirements to relying on liquidity redistributed through the markets will take place too quickly and so leave some banks without adequate resources. This was a concern when the Governing Council started planning to wind up the second series of TLTROs in 2018. What national central banks discovered was that too many institutions would come under stress due to the change in central bank lending policy. The challenge was greatest for the smallest banks. [12]

The third series of TLTROs announced in September 2019 was designed as a transitionary measure to create more time for adjustment. The rapid expansion of that programme during the pandemic was unexpected, as was the novel pricing structure that the Governing Council used to ensure that commercial banks would take full advantage of the programme. This modified programme was a success in terms of distributing liquidity across financial institutions in the euro area. [13] Nevertheless, the challenge remains to ensure those institutions have sufficient time to make the transition. Alternatively, central banks may need to reverse this policy and launch a fourth round of long-term refinancing operations as they did in 2019.

Government finances and the ECB

So far there is no discussion of a fourth round of TLTROs. Instead, the focus within the Governing Council is on quantitative tightening. The goal is to remove excess liquidity from the financial system. The challenge is to avoid destabilizing sovereign debt markets at the same time. [14] This explains why the creation of a transmission protection instrument (TPI) last July was a necessary precursor to the decision to run down the TLTRO programme quickly and to withhold reinvesting part of the maturing principal on the asset purchase programme. If such actions were to destabilize European sovereign debt markets, the Governing Council could deploy the TPI to restore stability. [15]

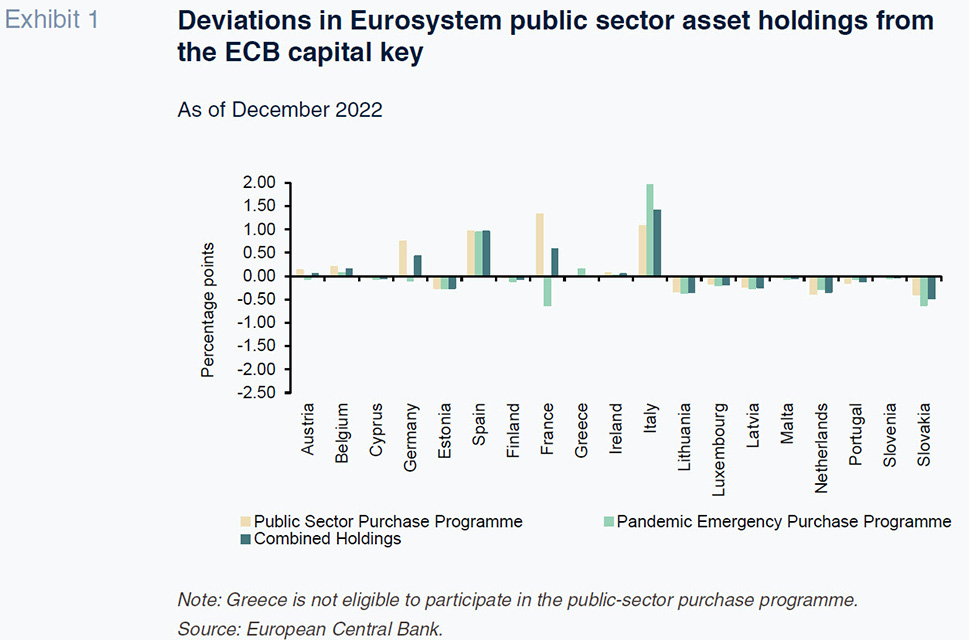

The need to ensure stability in sovereign debt markets also explains why there is currently no discussion of withholding maturing principal on assets held under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). That programme has a legal basis that is subtly different from the large-scale purchase programme that started in 2015. Purchases of government securities in the large-scale asset purchase programme – called the “public sector purchase programme” or PSPP – should roughly follow the same proportions that euro area Member States pay into the capital of the European Central Bank. By contrast, purchases under the PEPP are allowed to depart from the “capital key”, and so can be made more flexibly. Hence, the Governing Council announced last June that it would use the reinvestment of maturing principal on assets held under the PEPP programme as a first line of defence against instability in sovereign debt markets. [16]

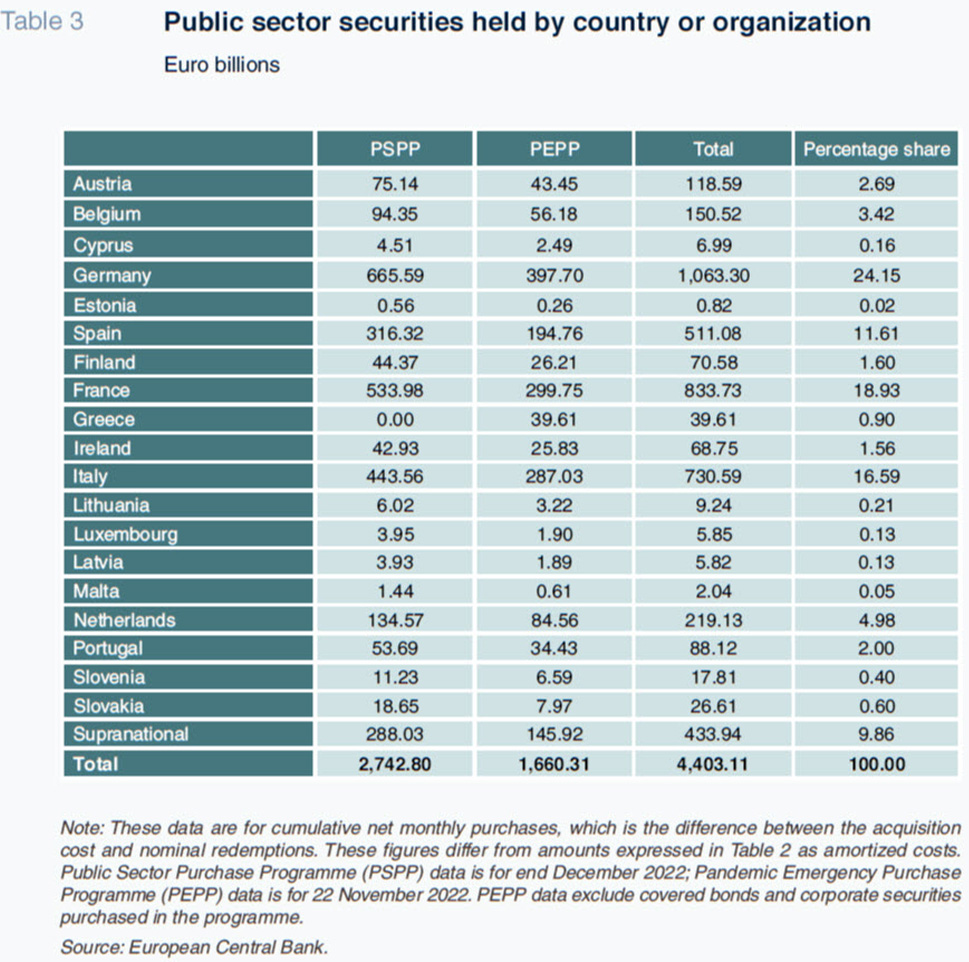

The combination of reinvestment of PEPP holdings and the possible deployment of the TPI has succeeded in maintaining stability in European sovereign debt markets. So long as that stability remains in place, the ECB has space not only to raise interest rates but also to shrink the Eurosystem’s collective balance sheet. The risk for government finances, however, is that any quantitative tightening will have a disproportionate impact on government financing in specific member states. Specifically, it is that those governments with the most bonds held by the Eurosystem will be most at risk of funding challenges as an increasing share of those bonds are effectively released onto the market when the central banks do not roll them over on maturity. Here the focus is primarily on Italy because Greek government bonds have never been eligible for purchase under the PSPP (see Table 3).

The Italian government is well-aware of the risk it faces. It is also aware that the ECB would not intervene to support Italian sovereign debt prices if the government chose to defy European macroeconomic policy coordination or to challenge European fiscal rules directly. As a result, the government that came to power in September 2022 has followed a conservative economic policy agenda even when doing so contradicts electoral commitments made by the right-wing coalition partners in previous elections. Indeed, during the most recent electoral campaign, the new prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, ran on a platform of fiscal responsibility and openly clashed with her own coalition partners. Her party emerged as the strongest within the coalition at the ballot box and since forming the government her position has only strengthened. In that sense, the political risk has been mitigated. [17]

The complicating factor is that governments across Europe need to tap into the markets to blunt the impact of high energy prices on households and to fund their transition to new energy resources. This borrowing comes on top of funds that the European Commission has raised and will raise to fund the pandemic recovery programme, Next Generation EU, and the new energy investment initiative, REPowerEU. As a result, government and supranational demand for credit will reach new highs even as European central banks begin to withdraw from the markets. According to reporting by Marcus Ashworth at Bloomberg, “the 10 largest euro nations are expected to sell some €1.3 trillion” in 2023, of which “around €340 billion” will be net new supply of debt. [18] Importantly, the German government will be the largest issuer of new debt. This new German demand for credit could put further downward pressure on bond prices at a time of relatively weak demand from investors, and so raise the cost of borrowing across the euro area.

This combination of factors creates two different risks for the ECB, both of which are political. The first risk is that the Italian government will lay blame for any high cost of government borrowing on the ECB’s interest rate rises. This criticism works domestically because it allows the new Italian government to deflect blame for tight fiscal circumstance without raising concerns among investors that it challenges European macroeconomic policy coordination. The second risk is that German Eurosceptics will complain that the ECB is not only failing to tackle inflation but also underwriting Italian public finances. They will base this argument on the disproportionality in PEPP holdings, even though this tends to favour Germany as well, given the large volume of government debt that country has in circulation. The point to note is that the more the Governing Council succeeds in winding down the PSPP, the more pronounced the disproportionality of its PEPP holding will rise to the surface (see Exhibit 1).

Such criticism of the ECB is already easy to find in the press of both Italy and Germany. In many ways that should be of little concern. The ECB’s political independence is not at risk and so long as such criticism is tied to events it will also whither away. The concern arises because of the possibility of an exogenous shock to European sovereign debt markets that might force the Governing Council to trigger the transmission protection instrument or, as a last resort, the programme for outright monetary transactions created by Mario Draghi in 2012. That kind of support might not be available for Italy so long as the Meloni government refuses to complete the ratification of the new treaty for the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) or, in extremis, to sign up for an ESM support programme. [19] So far Meloni has dragged her feet on ratifying the new ESM treaty – even though most observers believe her government will take that step – and ruled out asking for ESM support. That leaves the Governing Council to rely on reinvestment of maturing principal on the PEPP holdings within the Eurosystem to stabilize Italian sovereign debt markets. The only alternative would be to create some new instrument. That is always possible. Central banks have shown over the past two decades that new instruments or new uses of existing instruments can always be invented. [20] Nevertheless, doing so would raise additional risks as well as opportunities.

The coming debate

The risks associated with the ECB’s quantitative tightening run alongside the opportunities that policy change brings to normalize monetary conditions across the euro area. Identifying those risks is not the same as criticizing the new policy. Rather, it suggests the new agenda for conversation. As Governing Council members identify opportunities to slow the pace of interest rates rises or even pause in their monetary tightening, they will necessarily turn to focus on those issues that arise around the retirement of targeted long-term refinancing operations and the shrinking of the collective balance sheet of the Eurosystem. Those issues focus primarily on the impact that this will have on the cost of funding or MREL liquidity requirements in the banking system and government finances for those governments in the euro area. They will also focus on the instruments available for crisis management if there is some external shock to European sovereign debt markets. These will not be easy conversations because the distribution of costs and benefits will not be even or perceived as equitable. Nevertheless, there is no alternative to confronting those risks. The ECB must pair its monetary tightening with a quantitative tightening if it is to succeed in tackling inflation in the euro area.

Notes

Lagarde ECB press conference from 15 December 2022.

Lagarde ECB press conference from 15 December 2022.

See Francesca Barbiero, Miguel Boucinha, and Lorenzo Burlon, “TLTRO III and Bank Lending Conditions,” ECB Economic Bulletin, 6 (Frankfurt: European Central Bank, 2021) pp. 104-127.

See European Repo Market Survey 2022 (Zurich: International Capital Market Association, 2022) p. 35.

Cathal McElroy, “Eurozone Banks Unfazed as ECB Mulls Closing Cheap Funding Loophole,” S&P Global Market Intelligence (13 July 2022).

For the use of weak collateral to access TLTRO funding in Italy, see Annino Agnes, Paola Antilici, and Gianluca Mosconi, “Le TLTRO e la disponibilità di garazie in Italia,” Mercati, infrastrutture, sistemi di pagamento: Approfondimenti 12 (Roma: Banca d’Italia, 2021).

Alexander Weber, “ECB’s Cheap-Loan Repayments Slow to €63 Billion in Latest Round,” Bloomberg Government (13 January 2023).

Priscila Azevedo Rocha, Paul Cohen and Colin Keatinge, “Banks Flood Europe’s Bond Market as Cheap ECB Loan Program Fades,” Bloomberg Government (13 January 2023).

See Barbiero, Boucinha, and Burlon, “TLTRO III and Bank Lending Conditions.”

See Erik Jones, “The ECB’s Policy Conundrum.” SEFO – Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 11(4) (2022) pp. 47-54.

See “The Transmission Protection Instrument,” (Frankfurt: ECB Press Release, 21 July 2022).

See “Statement After the Ad Hoc Meeting of the ECB Governing Council,” (Frankfurt: ECB Press Release, 15 June 2022).

See Erik Jones, “Italy’s Hard Truths.” Journal of Democracy, 34(1) (2023) pp. 21-35.

See Marcus Ashworth, “Europe’s Coming Bond Avalanche Will Test ECB.” Bloomberg Government (6 January 2023).

There was an interesting exchange between Lagarde and journalists on this point in the December press conference.

See Jagjit S. Chadha, The Money Minders: The Parables, Trade-Offs, and Lags of Central Banking (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Erik Jones. Professor and Director of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute