The ECB’s new look

The results of the ECB’s monetary strategy review announced in July suggest Christine Lagarde has succeeded in her promise to transform how the ECB works and how it communicates with the outside world. However, her first real test will come as the Bank begins to unwind its unconventional monetary policy instruments.

Abstract: The ECB announced the results of its monetary policy strategy review in July. Significantly, the Governing Council has adopted a 2% symmetric inflation target. However, the way monetary policy makers push back against any deviation from their target is not symmetrical. The new strategy also envisions the eventual inclusion of owner-occupied housing in its inflation calculations, though this will not take effect immediately. The strategy introduces three constraints on the Governing Council’s room for manoeuvre. One stems from the ‘proportionality of its decisions and potential side effects’. The second is the need to preserve the function of the monetary transmission mechanism while the third relates to the need to maintain financial stability. Lastly, the new monetary strategy places the spotlight on monetary policy interest rates, while saying less about the use of other less conventional policy instruments, like direct asset purchases or TLTROs. The distinction between these instruments matters because the logic behind any recalibration can differ and because of their role in determining the proportionality of monetary action. Lagarde may have delivered on her promise to transform how the ECB makes monetary policy, however, she will face her first major test as the ECB seeks to unwind its unconventional monetary policy instruments.

Introduction

When Christine Lagarde was named to succeed Mario Draghi as European Central Bank (ECB) President in September 2019, she promised to transform how the ECB works and how it communicates with the outside world. That promise took almost two years to deliver, thanks largely to the COVID-19 pandemic. By summer 2021, however, Lagarde was ready to unveil the ECB’s new look. The results of the strategic review came out on July 8th; [1] the first meeting of the Governing Council to apply the new rules took place less than two weeks later.

For most ECB watchers, however, the extent of the change became apparent during the press conference held on July 22nd to announce the monetary policy decisions. [2] As Lagarde outlined the results of the Governing Council meeting, she did so in a language and format that was a sharp break from tradition. In the discussion that followed, journalists struggled to pin down the implications of what she said despite Lagarde expressing her hope that the message she delivered was clear. By the September 9th press conference, the new pattern of communication was less unfamiliar. [3] Nevertheless, it was obvious that Lagarde’s ECB is now very different.

Three elements are distinctive in the ECB’s new way of making and communicating monetary policy. The first is the identification of price stability and the approach monetary policymakers should take in trying to achieve that objective. The second is the link between interest rates and bond purchases or between conventional and more unconventional monetary policy instruments and settings. The third lies in the structure of forward guidance, meaning both assertions about how economic data inform policy actions and the language with which those assertions are made. By implication, this element also relates to the control over the messaging coming from the ECB President and other members of the Governing Council.

When you add these elements together, they suggest that Lagarde’s new look ECB is likely to be more transparent and accountable, but also more predictable and slower moving. In her July 22nd press conference, Lagarde summarized the new approach as ‘steady hands’ and ‘patience in order to gain confidence’. [4] What remains to be seen is whether such an approach will be flexible enough to respond to what could be rapidly changing circumstances. Given the potential for central bank liquidity created during the global economic and financial crisis, the European sovereign debt crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic to translate into accelerating price and wage inflation, the test of this new policy framework may be close at hand.

Fulfilling the mandate

The monetary strategy announced on July 8th contains several innovations. [5] The Governing Council will have a symmetrical target of expected inflation over the medium- term of two percent per annum, instead of the old asymmetrical target that defined price stability as being below but close to two percent. The distinction here is subtle. This new target does not define price stability as a two percent annual rate of inflation, or as two percent plus or minus a fixed variation, up or down. Instead, it describes the conditions within which ‘price stability’ as a policy objective will be achieved. By implication, the actual measure of inflation is not a measure of the success of the policy. Actual inflation may turn out to be above or below two percent per annum depending upon the circumstances. So long as expected inflation is close to the target, then the Governing Council will be fulfilling its mandate.

The target is symmetrical. That means the Governing Council should worry as much about inflation that is too low as inflation that is too high. The reason is to ensure that price inflation has a positive buffer. Rates of inflation that are too low put downward pressure on wages. They also put downward pressure on interest rates which limits monetary policymakers’ room for manoeuvre. At the same time, excessively high interest rates tend to accelerate as they fold into wage negotiations and price setting. This symmetry of concern explains how a forward-looking target connects to price stability. So long as economic actors anticipate that the inflation buffer will remain positive and consistent, they will leave enough room for actors to respond to any deviation in the private sector and for monetary authorities to push back against any excesses.

The way monetary policy makers push back against any deviation from their target is not symmetrical, however. On the contrary, the approach to that target is sensitive to the challenges monetary policymakers face when their main policy rates are close to zero, and so allows for some overshooting when responding to inflation rates that are systematically too low. The idea is that monetary policymakers will need to be more aggressive when their instruments are less effective. Once they have restored the positive inflation buffer, however, they can recalibrate their approach to focus more tightly on the target. In this sense overshooting from below is better than overshooting from above, because the ability for monetary policymakers to correct course is stronger when inflation is higher than when it is lower.

The new strategy also changes the measure of inflation. Eventually, the statistics will include price changes for owner-occupied housing. The objective is to make the index for consumer prices more representative of the impact on households. In this way, the goal of price stability will be more consistent with the lived experience of consumers. That should make the actions of the Governing Council more transparent. Nevertheless, such transparency will always be limited. The new index will still reflect aggregate conditions across the monetary union. No household lives in that aggregate, and there will continue to be variation in performance around the mean. What the change will do is take some of the structural bias out of that variance so that households in countries with consistently higher price increases in owner-occupied housing feel less systematically disadvantages by the common monetary policy.

The new strategy took effect as soon as it was announced. Even so, not every aspect became operational at the same time. The change in the target and the approach have immediate effect; the change in the price bundle will have to wait until European and national statistical authorities are able to compile standardized measures to feed into the harmonized index. Lagarde made it clear in her July 22nd press conference that this statistical adjustment is a policy priority both for the ECB and for the European Commission, which houses the European statistical agency, Eurostat. [6] Designing, collecting, and testing the new data will nevertheless take time. In the interim, the Governing Council will look at separate indexes for house price inflation as one source of information among many for how prices in the euro area are developing.

The strategy introduces three constraints on the Governing Council’s room for manoeuvre. One stems from the ‘proportionality of its decisions and potential side effects’. [7] The idea is that the pursuit of price stability should not do unnecessary damage to the real economy, meaning growth and employment; it should not impose undue financial costs on savers or investors either. This is a soft constraint insofar as such analysis is routinely baked into monetary policymaking; it is even softer when the judgments around the necessity of specific policy actions must be made.

The other two constraints are more rigid. The first of these is the need to preserve the function of the ‘monetary transmission mechanism’, which is the collection of financial channels through which monetary policy decisions translate into economic activity. The ECB cannot use its instruments to steer the economy if this transmission mechanism is broken. The second more rigid constraint is the need to maintain financial stability. The new strategy underscores that ‘financial stability is a precondition for price stability’.

[8] This is true not only because there is no monetary transmission mechanism when the financial system is at risk of collapse, but also because a collapse in the financial system tends to propagate quickly through the real economy. Hence, the Governing Council can only fulfil its mandate if the financial system is stable, and the monetary transmission mechanism is functioning.

Calibrating the instruments

The new monetary strategy places the spotlight on the monetary policy interest rates. This includes the deposit rate paid to banks for holding excess reserves with their central bank, the main refinancing rate charged to commercial banks when they borrow money from their central bank to meet their liquidity maintenance requirements, and the marginal lending rate charged to commercial banks when they need to borrow additional funds to meet their requirements during the liquidity maintenance period. These are the standard instruments of monetary policy that central bankers use in normal times to steer the economy, raising or lowering the deposit rate to change the incentives for commercial banks to hold excess liquidity and moving the lending rates to influence the cost of borrowing and therefore the cost banks pass on when lending.

Currently, these instruments are set in non-standard ways. The deposit rate is negative, thereby acting as a tax on excess reserves rather than a form of remuneration. The main refinancing rate is zero yet banks rarely if ever access that rate because they can get liquidity more cheaply from one another as banks with excess liquidity seek to pay a lower tax on their holdings. Although the marginal lending facility remains positive, it is accessed even less frequently (Table 1).

The question is when the Governing Council will begin to raise its policy rates to bring them into something that looks more normal. This would involve a deposit rate that is either zero or positive with the two lending rates significantly above zero. Under the new strategy, that recalibration can only begin to take place once there are clear signs that inflation rates are accelerating consistently enough to rise above the two percent target over the medium- term. Explaining what that looks like is a matter for forward guidance and not policy calibration – it tells market participants how to anticipate a policy change rather than telling policymakers how much to alter the settings on their instruments. By implication, the actual decision to reset the instruments lies somewhere in the future. When the Governing Council debated this point during the July monetary policy meeting, the main questions surrounded whether and how policymakers would recognize when it was time to act.

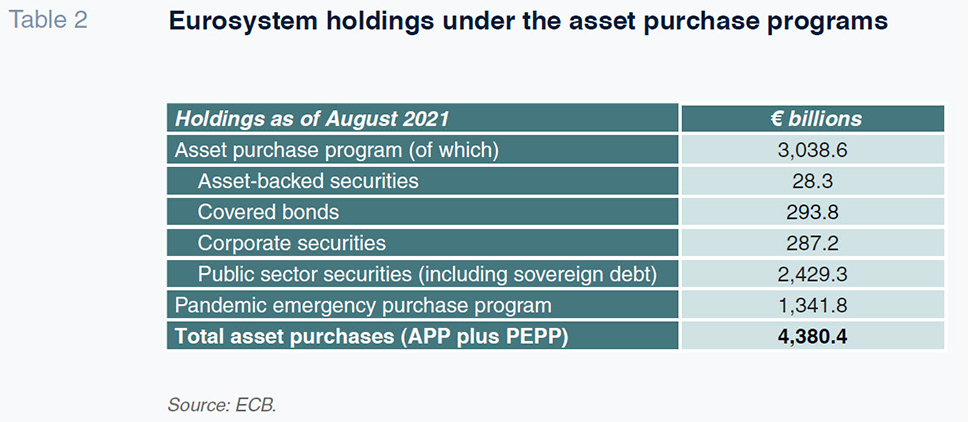

The new strategy says less about the use of other policy instruments, like direct asset purchases or targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). These are the instruments the Governing Council developed as interest rates approached the zero lower bound. Their goal is to address the constraints within which monetary policymakers operate. The longer-term refinancing operations were created initially to underpin financial stability. The direct asset purchases served the same goal but also ensured the continued operation of the monetary transmission mechanism. The use of these instruments expanded during the pandemic as policymakers struggled to contain the economic consequences of societal lockdowns and prolonged social distancing requirements. The use of these instruments has been dramatic, amounting to more than € 4 trillion in direct purchases since 2015 (Table 2).

The distinction between standard and less conventional instruments is important in the new strategy because the logic behind any recalibration of those instruments can be different. For example, a lift-off in interest rates will depend upon achieving the Governing Council’s price stability objective. Conversely, a recalibration of asset purchases under the ‘pandemic emergency purchase program’ (PEPP) reflects an end to the pandemic emergency due to the success of the vaccination program. This distinction was central to the September monetary policy decisions, where the Governing Council announced that it would scale back its purchases under the PEPP during the fourth quarter of 2021, while at the same time admitting that it remained far from achieving its mandate. [9]

The distinction between standard and non-standard instruments is also important to interpret the proportionality of monetary actions. At her July press conference, Lagarde was asked how she would defend the ECB against the charge that its asset purchases during the pandemic constitute monetary financing. Her response was to reject the premise of the question; given the scale of the economic crisis, ‘we had to do what we had to do’.

[10] The safeguards against monetary financing can apply once the crisis is past. The ‘proportionality’ of the Governing Council’s actions swings both ways in that sense.

The challenge of having monetary instruments deployed for different reasons is to ensure coherence in any monetary accommodation or tightening. The PEPP may be intended to respond to the unique circumstances created by the pandemic, but those additional asset purchases are nevertheless having an impact on market expectations of inflation. Consequently, withdrawing those purchases will have a reverse impact. The Governing Council may see the scale down announced in September as a ‘recalibration’, in Lagarde’s formulation, but market participants will still see it as a (modest) monetary tightening.

Explaining the separate logic behind the decision is also a challenge. Already in July, journalists were quizzing Lagarde about the Governing Council’s ‘knowledge of pandemics’; [11] when the question came up again in September, Lagarde pivoted to focus on when ‘the economy will have recovered in such a way that the downward impact of the pandemic on our inflation outlook has been resorbed.’ [12] She then admitted that the real questions surrounding the PEPP will be addressed only in December. That is also when the Governing Council will debate the future of the more general ‘asset purchase program’, and the TLTROs. In other words, where the July Governing Council focused narrowly on the new strategy for interest rates, the December Governing Council will focus on those more unconventional instruments.

Managing expectations and controlling the message

The ECB’s communication with markets is another tool for monetary policy insofar as it plays a crucial role in shaping market expectations. The new strategy complicates that communication in subtle ways. The problem is not the identification of the numerical target but in connecting that target to macroeconomic data and explaining how changes in those data inform changes in the policy instruments. Consider three illustrations, all related to the use of monetary policy interest rates: the identification of the ‘medium-term’; the assessment of changes in expectations; and the tolerance of ‘overshooting’, particularly when monetary policy makers start with interest rates close to the zero lower bound.

The identification of the medium-term is complicated because it involves official forecasts, surveys of professional forecasters, and market indicators. When the Governing Council deliberated about how to communicate this notion to the market in its July 2021 policy meeting, the Chief Economist, Philip Lane, came up with a three-fold test: inflation should reach the target well before the end of the official forecast period, that inflation should be ‘durable’, and that inflation should be reflected in underlying movements of the most stable parts of the price index (meaning those that exclude energy and food). The members of the Governing Council broadly accepted this formulation. Nevertheless, they were divided on whether the focus for attention should lie closer to the present, on actual inflation rates, or further into the future, on longer-term expected rates. The problem is that focusing on the present risks introducing too much volatility into the policy, which in turn undermines the policy’s medium-term orientation. However, focusing on the future threatens to mitigate responsiveness, thereby damaging the policy’s credibility. [13]

Pegging the medium-term on the forecast period offers a compromise between the shorter and longer-term positions. Even that compromise introduced ambiguity, however. When Lagarde set out Lane’s three-fold test during the July press conference, the journalists immediately pressed her on what the Governing Council means by the length of the forecast period and how long before that end inflation should converge on the target. At that point, Lagarde had to admit (in response to two different questions) that the forecast period has different lengths depending upon the time of the year. At the start and end of the calendar year, the forecast period looks three years ahead; in the middle of the calendar year, it looks ahead only two-and-a-half years. [14] By implication, it is more reasonable to expect policy changes in response to the December projections –which add a year to the forecast period– than at one of those meetings that falls between forecasts, like October. This prompted one journalist to ask what the Governing Council will discuss when it meets then. [15]

The way in which the bank will assess inflation expectations and the tolerance of overshooting were other areas of ambiguity. Although the Governing Council has a new strategy, it remains bound to the same data for capturing market sentiments. When journalists confronted Lagarde at her September press conference with movements in specific indicators, including one that had been identified by former ECB President, Mario Draghi, as particularly important in August 2014, Lagarde responded that ‘we are data-dependent in our policy determination, but we want to have a look at a whole range of such data’.

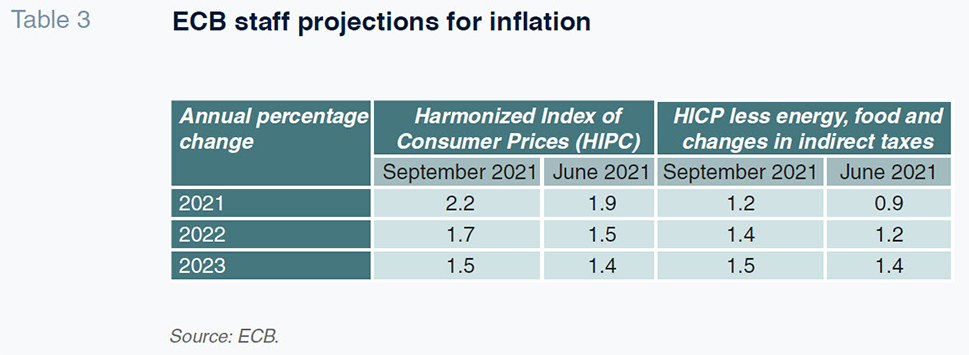

[16] She made a similar point about ‘looking through’ currently high rates of inflation, both across the euro area and in some of the larger euro area member states (Table 3).

The latest projections show that actual inflation is already overshooting the target. Nevertheless, core inflation remains subdued. Lagarde set out several reasons why the current pace of price increases is likely to slow over the next two years. These arguments are not universally accepted. We know from the monetary policy account for the July meeting, for example, that there are members of the Governing Council who worry that inflation could accelerate rapidly.

Lagarde refused to be drawn into the debate. Instead, she admitted that perceptions may be different from the arguments she put forward: ‘it is the case that in many countries in the euro area, people are seeing prices increase and they can feel it.’ [17] She also admitted that the Governing Council should prepare to adjust should the circumstances change. This is a standard line of argument, but it rests on top of a greater openness to disagreement both within the Governing Council and outside. At the July press conference, Lagarde admitted that there were dissenting voices. Toward the end of the meeting, she even invited journalists to seek them out and report what they had to say. That happened in the run up to the September meeting. With Lagarde’s new communication strategy, it is not clear that these voices of dissent made much of a difference.

‘The lady’s not for tapering’

Lagarde’s new look ECB appears to be more confident in its ability to explain and defend its monetary strategy. The quip she used in response to questions at the September 9th press conference was more important for its allusion to Margaret Thatcher’s politics of conviction than for what it told us about the future of asset purchase. Lagarde also appears to be more effective in communicating that strategy despite the inevitable ambiguities. However, it is still early days. The message about interest rates is clear, but the future of asset purchases and other more unconventional instruments is less certain. The big questions will be decided at the December 2021 monetary policy meeting. Lagarde has delivered on her promise to transform how the ECB makes monetary policy. As she looks ahead to unwinding those unconventional monetary policy instruments, her new strategy will face its first major test.

Notes

Erik Jones. Director of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute and Professor of European Studies and International Political Economy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (on leave)