Stress tests and other challenges for Spanish banks

The stress tests carried out by the European authorities showed that the Spanish banking sector looks highly resilient to adverse scenarios, despite the fact that the scenario modelled for Spain was among the toughest in the eurozone. Nevertheless, transition towards an even more stringent regulatory environment in terms of capital adequacy suggests that Spanish banks will have to continue to bolster their own funds over the coming years.

Abstract: This summer’s European stress tests occurred at a time of shifting expectations for the European banking sector, including the return of dividend payments and a challenging monetary environment. The tests, which covered 75% of European banking assets, used the banks’ common equity tier 1 (CET1) ratio as of year-end 2020 as their baseline and examined the period of 2021 to 2023. The regulators concluded that European banks have enough capital to withstand an adverse economic scenario. Banks’ average CET1 ratio fell 5.2 percentage points under the adverse scenario, with credit risk, market risk, and income generation capacity the main drivers of capital depletion. The starting CET1 levels for the Spanish banks is generally lower, but capital depletion in the adverse scenario is also lower. This indicates that although the Spanish banks continue to present slightly below-average capital ratios, they are more resilient than the average European bank. Importantly, the results of these tests will influence Pillar 2 Guidance and the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process. On top of these pressures, banks will have to contend with an uneven regulatory environment with FinTechs and growing sensitivity surrounding ESG-related issues.

Introduction

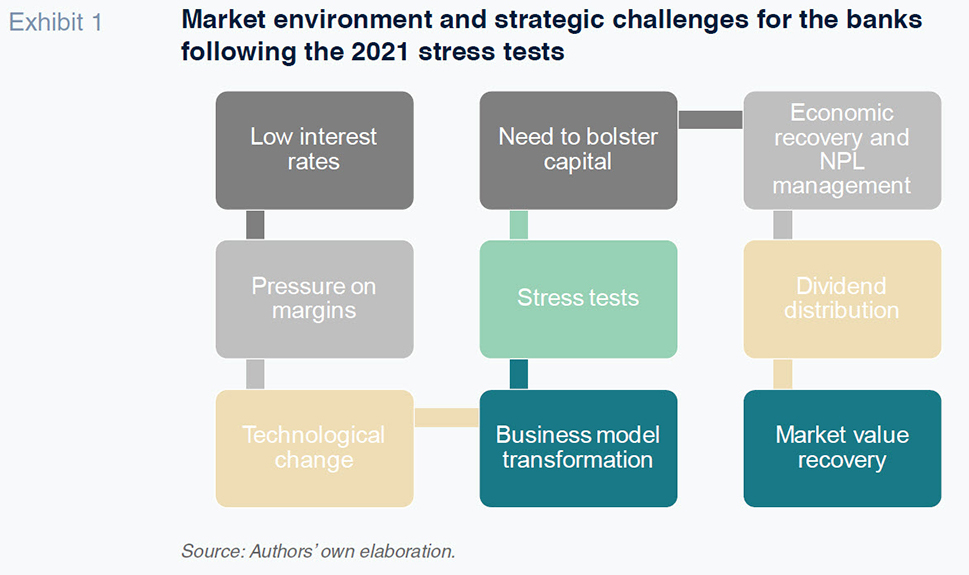

The challenging economic and financial environment coupled with the increasing digitalisation of retail banking service mean banks are forced to pursue multiple simultaneous strategies. (Exhibit 1 provides a snapshot of the key forces shaping the banking business today.) Against this backdrop, European banks underwent stress tests this past summer. Although initially scheduled for 2020, the limited visibility as to the impact of the health crisis convinced regulators to postpone the tests until 2021. The purpose of these tests is to analyse banks’ resilience in solvency terms to adverse macroeconomic shocks.

The 2021 stress tests were performed using adverse macroeconomic shocks, with the baseline scenario assuming a successful vaccination campaign would lead to an economic recovery during the latter half of the year. By modelling the worst case scenarios, the tests show whether specific entities need to take measures to reinforce their capital. Importantly, the tests took place at a time of shifting expectations for the European banking sector, including the return of dividend payments.

At the end of July, both the single supervisor and the Bank of Spain indicated that the projections for 2021-2023 pointed to an economic recovery, prompting them to eliminate the restrictions imposed on the distribution of earnings from September 30th, 2021. Nevertheless, in its press release, the European Central Bank cautioned banks to “remain prudent when deciding on dividends and share buy-backs, carefully considering the sustainability of their business model.” The ECB expanded its decision to all global systemically important banks from July 23rd and the Bank of Spain then extended it to all other systemically important banks in Spain. Spanish banks’ share prices appear to have benefitted from the decision. Following years of stock market turbulence, the Ibex Banks stock index gained over 80% between August 2020 and August 2021.

The monetary environment, however, is murkier. While the Federal Reserve appears to be headed for the gradual withdrawal of monetary stimulus in the near-term (as endorsed at the Jackson Hole Symposium at the end of August), the ECB will find it more difficult to claw back its bond buying program. Although the ECB has adopted a more flexible approach to the relationship between monetary policy decisions and inflation, the economic rebound and inflationary concerns are more subdued in the eurozone. As a result, the European monetary authority expects rates will remain ultra-low or even negative until at least 2022.

While the liquidity facilities provide the banks with a stable source of financing, benchmark interest rates continue to exert downward pressure on the banks’ net interest margins. On the upside, the recovery could foster growth in lending. However, banks will have to manage the spike in non-performance expected once COVID-19 business support measures expire.

General takeaways from the stress tests

The results of the stress tests were published on July 30th, 2021. They were managed by the European Banking Authority (EBA), which ran the tests for Europe’s 38 biggest banks, and the ECB, which performed them for 51 medium-sized institutions, covering 75% of total eurozone banking sector assets. The starting point was the banks’ common equity tier 1 (CET1) ratio as of year-end 2020. The tests cover the period of 2021 to 2023. The regulators concluded that that European banks have enough capital to withstand an adverse economic scenario. Under an adverse scenario, banks’ average CET1 ratio would fall from 15.1% to 9.9% over the three year period. That puts capital depletion at 5.2 percentage points.

According to the EBA and the ECB, the “main drivers of capital depletion are credit risk, market risk and income-generation capacity”. Compared to prior rounds of stress tests, it is worth noting that although the banks were in better shape at the start of the exercise (CET1 as of December 2020) compared to three years ago, capital depletion at the system level was higher. This reflects two trends in supervisory practices. Firstly, the banks have been required to hold higher capital buffers in the context of the gradual rollout of the Minimum Requirement for own funds and Eligible Liabilities (MREL). Secondly, the scenario modelled by the supervisory authorities was more severe than in the 2018 tests. The adverse scenarios vary depending on the economic forecasts for each country, with Spain assigned one of the harshest scenarios.

Broken down by size, the 38 largest banks tested by the EBA saw their CET1 ratio fall from 14.7% to 9.7% (5.2 percentage points) in the adverse scenario, while the 51 medium-sized banks’ capital decreased from 18.1% to 11.3% (6.8 percentage points). As indicated in the ECB’s press release, “the medium-sized banks are more affected by lower net interest income, lower net fee and commission income and lower trading income over the three-year horizon.”

The first key driver of banks’ capital depletion was credit risk. This is due to loan losses from the adverse scenario’s economic shock. Specifically, the EBA calculates that the 38 larger banks would incur credit losses of 308 billion euros in the adverse scenario. By comparison, potential market risk and operational risk losses are estimated at 74 billion euros and 49 billion euros, respectively.

How the Spanish banks fared

The adverse scenario modelled for the Spanish banks simulated contractions in GDP of 0.9% in 2021 and 2.8% in 2022, followed by growth of 0.5% in 2023. These scenarios also incorporated a hypothetical unemployment rate of 21.9%. While these scenarios are highly unlikely, their purpose is to understand how the banks would respond to the unexpected.

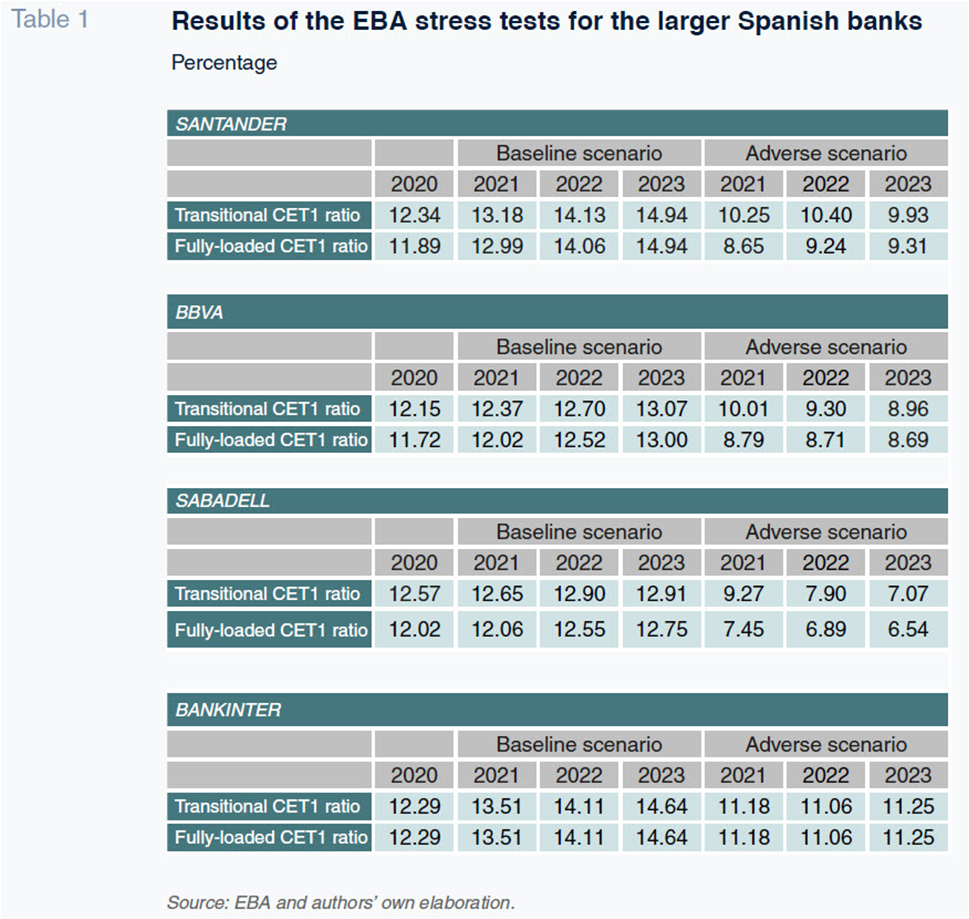

Four Spanish banking groups participated in the tests coordinated by the EBA: Santander, BBVA, Sabadell and Bankinter. Note that the EBA decided to exclude Caixabank and BFA Bankia as they were in the process of merging at the time. Table 1 provides the CET1 ratios on a transitional (i.e., under prevailing requirements) and fully loaded basis (i.e., as if all the regulatory requirements due to be implemented by 2022 were already in effect). At first glance, we observe a significant difference between the Spanish banks and the European average. The starting CET1 levels for the Spanish banks is generally lower, but capital depletion in the adverse scenario is also lower. This indicates that although the Spanish banks continue to present slightly below-average capital ratios, they are more resilient that the average European bank. This relative resiliency is attributed to the strength of the system’s retail model and client base, as well as the benefits of its substantial geographic diversification.

Comparing the banks’ fully-loaded CET1 ratios in 2020 with those estimated for 2023, capital depletion in the adverse scenario is estimated at 2.58 percentage points at Santander, 3.03 percentage points at BBVA, and 5.48 percentage points at Sabadell. Capital depletion at Bankinter was 1.04 percentage points. Notably, Bankinter has fully adopted all new regulatory requirements such that its fully loaded CET1 ratio coincides with its transitional ratio in the table.

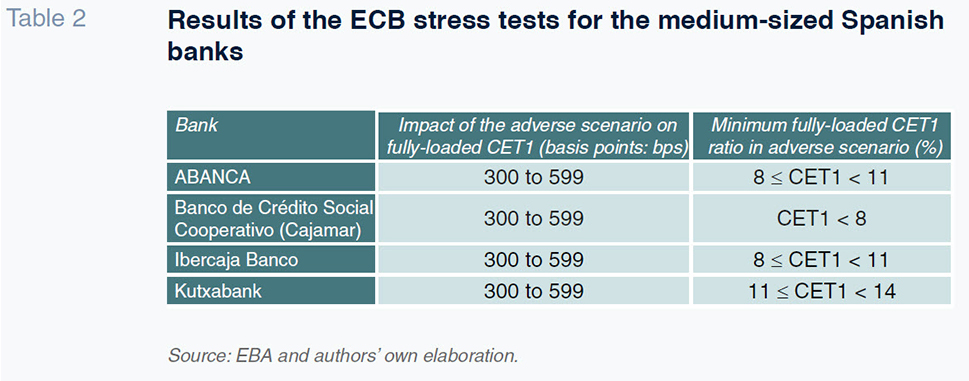

With respect to the medium-sized Spanish banks, the results are provided in ranges and evidence a notable degree of resilience (Table 2). The four banks analysed (Abanca, Banco Social de Crédito Cooperativo-Cajamar, Ibercaja Banco and Kutxabank) are expected to sustain fully-loaded CET1 capital depletion of between 300 and 599 basis points in the adverse scenario. Banco Social de Crédito Cooperativo’s CET1 ratio would end up a little below 8% in 2023, capital at Abanca and Ibercaja would fall between 8% and 11%, with Kutxabank coming in between 11% and 14%. Although the impact of the adverse scenario on the medium-sized banks is somewhat greater, these results show higher capital ratios than the European average, which translates into a stronger solvency position at the end of the projection period.

The aftermath of the tests: More capital, greater transformation and an emphasis on banks’ social role

The analysis provided in this paper shows that those Spanish banks that participated in the EBA and ECB stress tests are capable of withstanding adverse scenarios with satisfactory capital ratios, despite the relatively greater severity of the macroeconomic assumptions modelled. As in prior tests, no threshold was set to define the failure or success of the banks. It is important to highlight that the quantitative impact of the adverse stress test scenario is a key input for determining the level of Pillar 2 Guidance (P2G). Furthermore, some qualitative outcomes from the stress test exercise will be taken into account in the annual Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP). It is therefore worth considering the future direction of European stress tests and what the current and planned changes reveal in terms of the supervisory approach to the sector.

On account of the pandemic, the European supervisors continue to allow the banks to use capital buffers to absorb losses. The changes contemplated in the Pillar 2 solvency requirements, which address the management of expected losses, will not take effect until the end of 2022. The results of the stress tests are likely to be linked more closely to the Pillar 2 requirements and the banks’ capital buffers will have to be a bit bigger. Spanish banks have operated with somewhat tighter capital buffers and will therefore have to shore up their capital if they are to remain in a comfortable position in 2022. In a note published on July 29th, 2021, the Bank of Spain reported on its annual identification of so-called other systemically important institutions (O-SIIs), setting their capital buffers for 2022. Specifically, it set a 2022 capital buffer of 1% of risk-weighted assets (RWA) for Banco Santander and of 0.75% for BBVA. For Caixabank, following the merger with Bankia, it assigned a buffer of 0.375% of RWA for 2022, rising to 0.5% in 2023. Lastly, Banco Sabadell’s buffer was set at 0.25%.

Future stress tests will include requirements in relation to money laundering and fraud and will gradually incorporate sustainable financing. On top of these pressures, the monetary environment remains extraordinarily lax, eroding banking margins. We are also seeing growing competition from non-financial FinTech providers. Despite increased regulatory scrutiny, the playing field remains uneven, with established banks and FinTech firms subject to different sets of rules for similar functions.

Lastly, the general pace of technological change and growing social sensitivity are forcing the banks to take action to protect and nurture their corporate social responsibility. As a result, banks are placing a greater emphasis on ESG-related criteria. Additionally, banks are actively expanding the provision of traditional banking services to segments of the population that are less digitally savvy, including the elderly and those located in sparsely populated rural areas.

Santiago Carbó Valverde and Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas