Private investment: The weak link in Spain’s expansionary phase

Despite strong growth and unprecedented EU funding, private investment in Spain has failed to recover to pre-pandemic levels, reflecting a persistent gap between the country’s favourable macroeconomic conditions and corporate investment behaviour. Heightened uncertainty and structural impediments have limited the crowding-in effects of public investment, weakening incentives for firms to commit capital despite supportive financing conditions.

Abstract: Healthy economic growth coupled with strong inflows of European funds under Next Generation EU should have created a favourable climate for corporate investment, a key variable for productivity and future prosperity. However, private investment has lagged expectations while remaining below pre-pandemic levels. Indeed, despite a recent pick-up, gross fixed capital formation among the non-financial corporations lies 1.4% lower than in 2019, adjusting for inflation. This lag reflects the climate of uncertainty, at home and abroad, which has encouraged firms to delay investment decisions and accumulate surplus savings despite positive macroeconomic conditions. To unlock potential private investment flows, it is thus vital to tackle the impediments that undermine the knock-on effects of the Next Generation programme, including the need to increase legal certainty, strengthen institutional stability and diversify the financing instruments available to the economy.

Introduction

Investment plays a prominent role in the current environment of technological change and geopolitical tension. In his report on the future of European competitiveness, Mario Draghi attributed the EU’s economic decline relative to the U.S. to weak investment, particularly in innovation (Torres and González Simón, 2025). Investment is also vital to addressing Europe’s vulnerabilities vis-a-vis other superpowers, particularly in the areas of AI, energy and defence.

In the case of Spain, high economic growth coupled with the availability of a massive volume of European funds and the downtrend in interest rates, have created a climate ripe for investment. So far, however, the results are falling short of expectations (Torres et al., 2025). The goal of this paper is, on the basis of an analysis of the most recent trends, to look at some of the macroeconomic factors that may be shaping the current investment cycle.

Recent trends: Strong public investment versus lagging private investment

This paper focuses on productive investment, which excludes investment in housing. It is measured using gross fixed capital formation as per the national accounts. This aggregate encompasses the purchase of equipment and machinery, transport materials, intellectual property products (a category which serves as a proxy, albeit imperfect, for investment in intangibles) and infrastructure. Productive investment is primarily undertaken by the private sector (non-financial corporations) and the public sector (government).

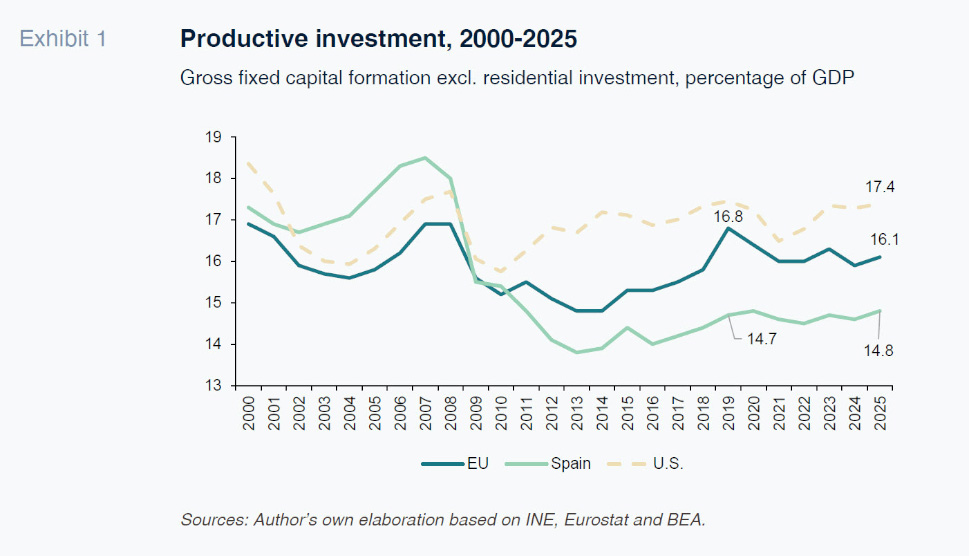

Broadly speaking, productive investment has fluctuated over time (Exhibit 1). During the real estate bubble, the percentage of domestic product earmarked to productive investment —a proxy for the sacrifice a country is willing to assume in deferring current consumption with the hope of improving its standard of living in the future—, reached very high levels, both in historical terms and by comparison with other advanced economies. With hindsight, it is clear that the accumulation of capital was excessive as many of the funds invested, financed by borrowing, fuelled a bubble, without reinforcing the country’s productive capacity. That episode provides tangible evidence of the fact that investment only leads to efficiency gains if the funds are well allocated, which in turn depends on the presence of a functional financial system and the macro-prudential controls, both of which failed at the time of the financial crisis.

More recently, investment has been more muted; following a slight recovery prior to the pandemic, the investment rate has been oscillating around low levels. Despite an uptick in 2025, the investment rate remains at 14.8% of GDP (average for the first half of the year), which is virtually the same as five years ago and below the level expected when the economy is as dynamic as it currently is.

Both the EU as a whole and the U.S. invest considerably more as a per cent of their GDP than Spain. It is encouraging that productive investment has increased in recent years but the trend is not yet sufficiently robust to close the gap with the main advanced economies.

Within productive investment, the weakest link is transport materials and, to a lesser degree, machinery and equipment. What these trends tell us is that businesses are still exercising caution when it comes to adding capacity, even during years of sharp economic growth. Investment in “Other buildings and structures”, a category which includes infrastructure, communication networks and non-residential buildings, has fluctuated around a slightly upward path. On the other hand, intangible assets are the most dynamic category. Recall that intangible assets and other buildings and structures are among the areas benefitting most from the NGEU funds. The overall picture, however, is that even with the boost provided by these funds, productive investment continues to lag the European average.

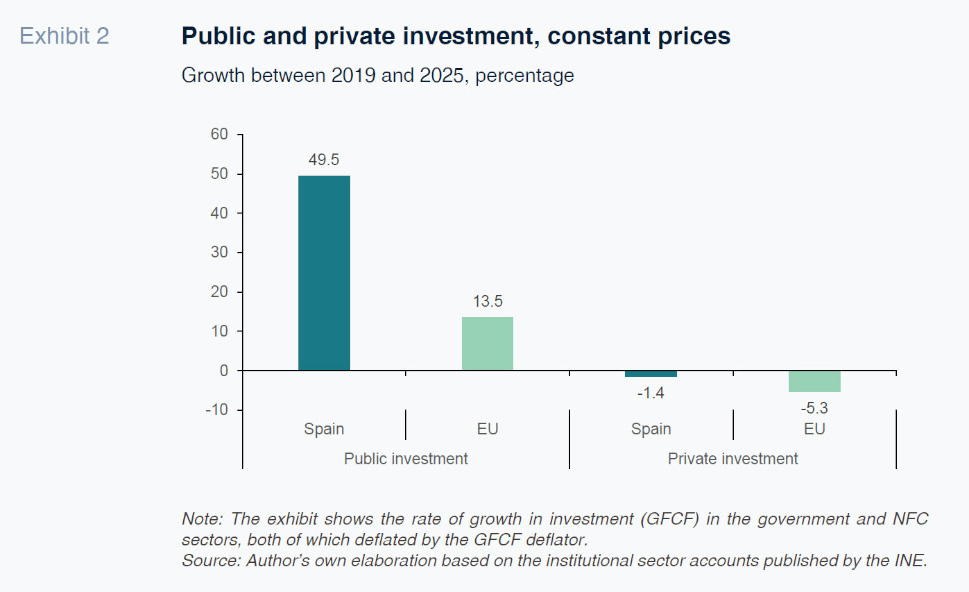

The key to this underperformance lies with lethargic corporate investment (Exhibit 2). Among the institutional sectors, the non-financial corporations have been the most lacklustre: their gross fixed capital formation has contracted by 1.4% since 2019, adjusting for inflation.

This lukewarm level of corporate investment is surprising for several reasons. Firstly, it contrasts with the trend in public sector investment, which has increased by nearly 50% over the same period (again in real terms), thanks to the lift from the European funds. These public funds were expected to have a bigger knock-on (or crowding-in) effect on private investment. By investing in collective goods, the state can create a climate conducive to private initiative. Indeed, a crowding-in effect was one of the specific targets of the European funds. Some of the strategic sector-specific plans assumed that private investment would be several times more than the public funds provided under the NGEU programme.

Secondly, Spanish corporations have gone through a period of growth theoretically conducive to adding to their capital stock. Their European peers, which have had to navigate a much harsher macroeconomic environment, have invested at similar rates to Spanish businesses (or even more in terms of GDP | Exhibit 1).

[1]

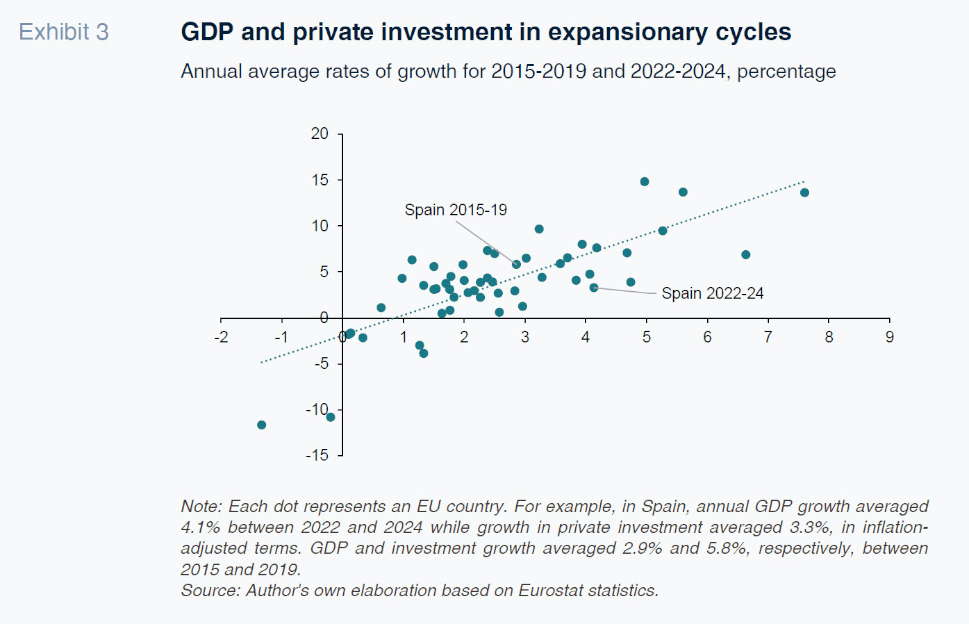

A positive macroeconomic context tends to boost private investment, a variable which is typically procyclical,

i.e. it amplifies cyclical swings. In fact, during the expansionary 2015-2019 period, private investment outpaced GDP growth in nearly all EU economies.

[2] In Spain, for example, annual growth in investment rebounded to 5.8%, nearly twice the growth observed in GDP over the same timeframe. The pandemic dealt a harsh blow, triggering unprecedented contraction in private investment, evidencing the pro-cyclical nature of this variable.

In the last few years, however, this procyclical behaviour has not held, at least in Spain, with investment increasing by 3.3% in the last three years (adjusting for inflation), which is nearly one point less than GDP, breaking with the historical correlation and exhibiting a lower elasticity than is observed in other European countries (Exhibit 3). By the same token, private investment has yet to revisit pre-pandemic levels, whereas GDP is already 10% above that mark.

The sectoral breakdown signals similarly sluggish private investment relative to public investment. Investment during the period was concentrated in the sectors that are direct recipients of public investment, namely government and defence, education and healthcare. In contrast, industry, a priority focus of the European funds, has registered modest growth. Even more surprisingly, the investment rate in the sectors related with tourism has fallen, perhaps due to the protracted effects of the pandemic. A similar pattern is on display in other European economies, evidencing a certain reluctance to invest in the sectors more closely entwined with tourism. On the other hand, the investment rate in professional services and information and communication services has increased sharply, albeit very much in line with the European experience.

The long shadow of uncertainty

The question is, therefore, why has private investment proven less dynamic than in previous growth cycles? In general terms, investment decisions depend on the future profits expected by businesses and the relationship between those profits and transaction costs. The decision is, in reality, a calculated bet, as the future is by definition uncertain, which is where both objective trends, such as enterprise sales and profits, and intangible factors, like investor and business sentiment, come into play. These factors all weigh on expectations for demand, prices, production costs and other variables taken into consideration when deciding whether to invest.

According to several studies, business profitability does not appear to be a constraint, at least in general terms.

[3] Although it is concerning that some sectors are having a hard time making money, in no instance does this circumstance appear to be discouraging or curtailing investment judging by the available studies. It is a fact that profits after tax and interest are already back above pre-pandemic levels, whereas investment has shrunk (adjusting for inflation in both cases).

Likewise, the trend in foreign direct investment (FDI) signals a relatively profitable ecosystem. FDI reflects the inflow of foreign capital in order to create companies, add to existing capacity or reinvest existing profits. It is therefore a good proxy for major international investors’ confidence in the future of the economy. Some forms of FDI do not necessarily or immediately translate into productive investment. For example, capital inflows can take the form of an injection of funds into existing companies without leading to new productive capacity, unlike other forms of FDI, such as the creation of production units or greenfield investments, which translate into investment almost right away. In general, however, FDI brings in stable funds for present or future productive development, unlike investments in securities, which are volatile in essence as their whole purpose is to deliver short-term gains.

On paper, FDI has continued to be a boon for the Spanish economy: the influx of foreign capital for productive uses has averaged 3.3% of GDP over the last five years, which is above the pre-pandemic contribution and also higher than the level observed in other advanced economies. This trend contrasts with the contraction in inbound FDI in the eurozone as a whole.

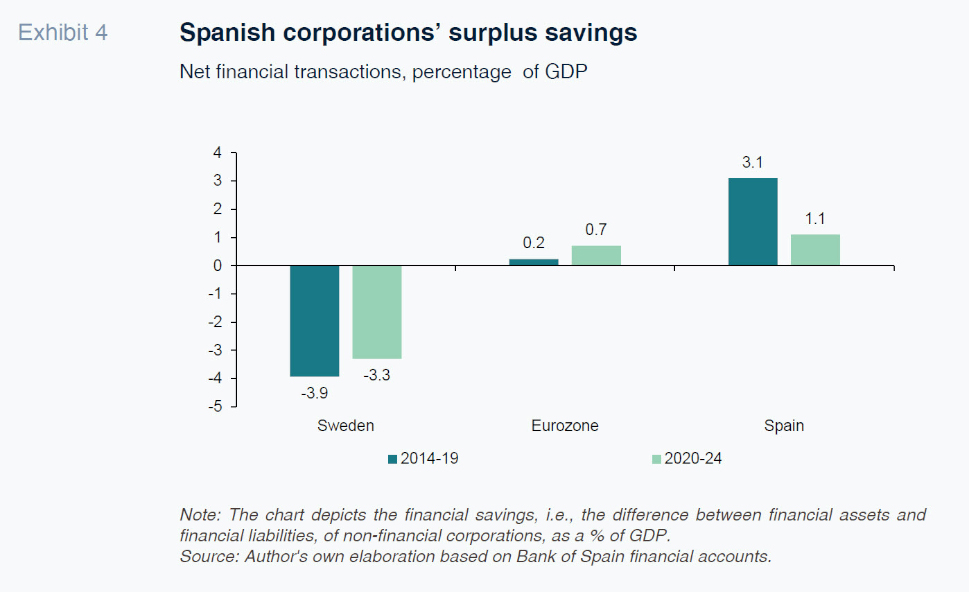

The most plausible explanation behind weak private investment lies with uncertainty and its corollary, namely surplus corporate savings. Indeed, the non-financial corporations have registered an uninterrupted net lending position since the real estate bubble burst rather than a borrowing requirement, as might be expected due to the very nature of corporate activity, which is to use external capital to finance growth. That surplus has been oscillating at between 10% and 20% of disposable income. Other European countries have similarly been recording a surplus, albeit generally of a lower magnitude (Exhibit 4). In economies like Sweden and the U.S., companies are tapping the markets to top up the savings generated, evidencing higher confidence in the future.

Surplus savings, when not invested in productive assets, are used in part to accumulate financial assets (such as cash, bank deposits, bonds and other financial instruments) and in part to repay liabilities. Specifically, the corporate sector has accumulated financial wealth (financial assets less financial liabilities) of around 2.2% of GDP per annum on average between 2014 and 2024. That is five times the eurozone average: in no other large EU economies have enterprises been more cautious in this respect. This has translated into sharp deleveraging, leaving enterprise debt at record lows and significantly below the European average.

The trend in surplus corporate savings is attributable to the prevailing uncertain climate. Risk is an omnipresent factor in investment decisions, which is why economic agents are particularly cautious during periods of uncertainty. By definition, the acquisition of a piece of equipment, such as a machine or software programme, is a financial bet made by a business today with the expectation of generating a return in the future.

[4] This is why uncertainty acts as a check, particularly when it is “fundamental”, meaning it is not possible to attribute a probability to different future scenarios.

[5] Uncertainty similarly affects expectations around the cost of capital, a key variable in companies’ investment decision-making.

[6]These past few years have been characterised by a succession of shocks for the investment climate, starting with the health crisis and followed by the onset of war in Ukraine and its ramifications for inflation and, more recently, the increase in U.S. import tariffs as geopolitical tension runs high.

Domestically, an unpredictable or fluctuating regulatory framework is also seen as a risk, which may have led some companies to park their profits in financial assets instead of investing them in productive assets. One recent study highlights the importance of economic policy uncertainty on investment decisions. Fernández Cerezo et al. (2025). The complexity of the paperwork involved in applying for the NGEU funds and the perceived delays in paying them out may also have inhibited or delayed investment decisions.

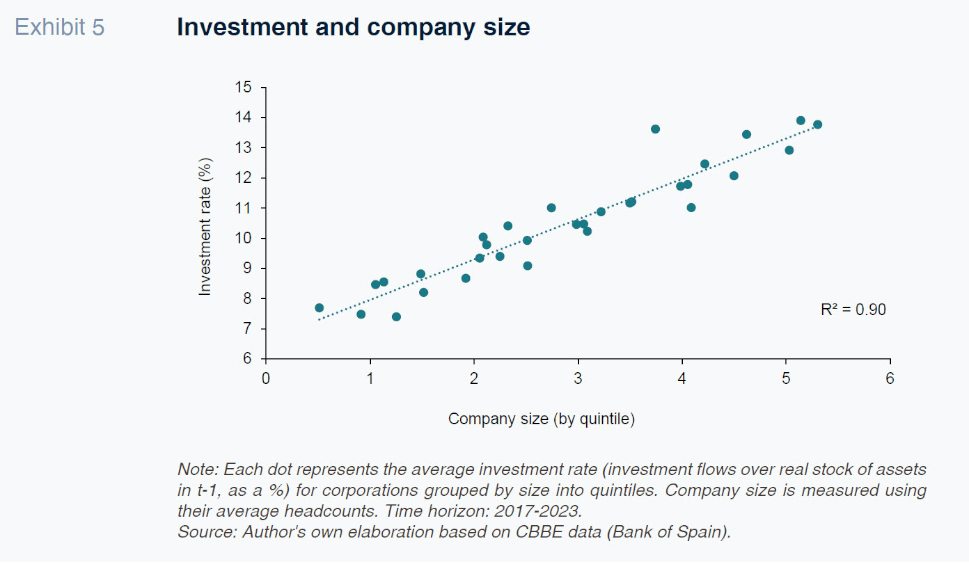

The climate of uncertainty may weigh more on investment decisions at small businesses, which comprise the bulk of the Spanish productive fabric, either because they lack the skilled professionals needed to address it, unlike the larger corporations which also have ready access to the more established consultants, or because their investment time horizons tend to be shorter. A fragmented productive system is, therefore, vulnerable to economic swings. In addition, small businesses face more difficulties than their larger peers when it comes to borrowing money. Bank loans embody a risk premium for small units, increasing the cost of their investments. By contrast, the established firms not only have access to cheaper financing, they can also attract non-bank funds by tapping the fixed-income and private equity markets directly, or turning to their shareholders. Hence the increasing correlation between investment rates and company size (Exhibit 5).

Key takeaways

The Spanish private sector is investing less than its European peers, which are in turn investing less than U.S. firms. The recent upward trend is encouraging, but probably not enough to reverse the situation, highlighting the importance of tackling the macroeconomic factors that are constraining corporations’ investment decisions.

The key lies with uncertainty, abroad and at home, underscoring the need to render Spanish and European economic policy more predictable. Matters are not being helped by the successive budget rollovers or, at the European level, faltering over the capital markets union initiative. A pressing priority is to increase the knock-on effect of public investment, boosted by the NGEU funds, on private investment, undertaking reforms designed to strengthen legal certainty, address other factors related with institutional stability, and diversify the financing instruments available to the economy, a matter of particular importance for small businesses.

Notes

Between 2019 and 2025, the investment rate of the non-financial corporations decreased by 1.9 percentage points relative to GDP, compared to an average EU contraction of 1.3 percentage points, calculated using Eurostat statistics.

Latvia and Luxembourg were the exceptions.

According to a recent study by the Bank of Spain based on its Business Activity Survey, profitability acts as a secondary constraint for both large and small enterprises (it is not that it is not a factor, just that at present it would not appear to be curtailing investment as much as other factors, such as uncertainty, for example). Refer to Fernández Cerezo et al. (2025).

According to a recent study, as many as four out of every five firms miscalculate their cost of capital when assessing investments, leading to defective resource allocation. Refer to Gormsen and Huber (2024).

Prestigious economists such as Keynes and Frank Knight made a clear distinction between the risks that might occur with a certain probability and fundamental uncertainty, which cannot be quantified. Refer to Dimand (2021).

See the paper by Vicente Salas in this issue of SEFO.

References

DIMAND, R. W. (2021). Keynes, Knight, and Fundamental Uncertainty: A Double Centenary 1921–2021.

Review of Political Economy, Taylor & Francis Journals, Vol. 33(4), 570-584, October.

FERNÁNDEZ CEREZO, A., PUENTE DÍAZ, S., and VEIGA DUARTE, R. (2025). Weak business investment in Spain following the pandemic: An analysis based on the Banco de España Business Activity Survey.

Bank of Spain Economic Bulletin 2025/Q1, Article 02.

https://www.bde.es/f/webbe/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/InformesBoletinesRevistas/BoletinEconomico/

25/T1/Files/be2501-art02e.pdf.

https://doi.org/10.53479/38946 GORMSEN, N. J., and HUBER, K. (2024). Firms’ Perceived Cost of Capital.

https://voices.uchicago.edu/gormsen/files/2024/07/GormsenHuber2024July.pdf SALAS FUMÁS, V. (2025). Economic profits and investment dynamics in Spanish non-financial Corporations.

SEFO, Vol. 15, No. 1, January 2026. Funcas.

TORRES, R., FERNÁNDEZ, M. J., and GÓMEZ DÍAZ, F. (2025). The Spanish economy’s growth cycle: Constraints and outlook through 2027.

SEFO, Vol. 14, No. 6, November 2025. Funcas.

https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/1-Torres-14-6.pdf TORRES, R., and GONZÁLEZ SIMÓN, M. A. (2025). The Draghi Report and the Spanish economy.

SEFO, Vol. 14, No. 1, January 2025. Funcas.

https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Torres-14-1-1.pdf

Raymond Torres. Head of macroeconomic and international analysis, Funcas