Generative AI and the future of work and education

Generative AI is reshaping labour markets primarily by reorganizing tasks within occupations rather than eliminating jobs outright, with uneven effects on wages, employment, and access to entry-level roles. These outcomes depend not only on technical capabilities, but also on human agency, institutional choices, and how education systems adapt to shifting expertise thresholds.

Abstract: Generative AI is already reshaping work, primarily by reorganizing tasks within occupations rather than eliminating jobs outright. Because jobs bundle tasks of varying difficulty, automation can either raise or lower expertise thresholds depending on which tasks are removed, producing outcomes in which wages and employment may move in opposite directions. Task-level evidence shows that roughly two-thirds of tasks removed since the late 1970s were routine, while abstract tasks account for most tasks added, pointing to increasingly divergent labour-market trajectories across AI-exposed occupations. Labour-market impacts will depend not only on technical capability but also on human agency and adoption choices. Firm-level evidence indicates seniority-biased technical change: junior employment declines following generative AI adoption—driven mainly by slower hiring—with reductions approaching 10% within two years. At the same time, AI offers opportunities in education by scaling expert feedback at low marginal cost, with randomized trials showing learning gains of around four percentage points. Economics education, in particular, is highly exposed to these changes but also well positioned to adapt, provided curricula shift toward AI literacy and complementary skills such as judgement, verification, communication, and applied project work. In Spain, where youth unemployment stood at 25.42% in Q3 2025, these dynamics make the early-career bottleneck especially salient, strengthening the case for expanding AI-enabled training capacity and redesigning school-to-work pathways, building on the demonstrated successes of dual vocational education.

Introduction

AI is best understood as a technology that reorganizes tasks within occupations. Because jobs bundle tasks of different difficulty, the same AI capability can lower barriers to entry in some roles while raising them in others, and it can increase wages in roles that shrink in employment. A task-based approach is therefore essential for predicting distributional effects and for designing education and training responses.

This essay compiles evidence from the economic literature to argue that the effects of AI on labour markets can be nuanced. Wages and employment can go up or down depending on the task composition of the different sectors. But humans can, and will, impact how this adoption process develops. One sector of the population that will be particularly impacted is that of young workers, as many tasks that were done by junior employees will be taken over by AI. As a result, education needs to be seriously rethought. However, AI also brings large opportunities for the educational sector, which may mitigate the impacts on young workers.

The future labour market: Expertise, task re-bundling, and human agency

Expertise and entry barriers

One of the most interesting perspectives on the impact of emerging technologies in the labour market is given by Autor and Thompson (2025). They start with a model that assumes an expertise hierarchy. More expert workers can perform the tasks of less expert workers, but not vice versa. Since occupations bundle tasks, workers must be able to perform all non-automated tasks in the bundle. The most expert remaining task therefore sets an entry threshold. Automation can lower that threshold by removing expert tasks (making it feasible for less expert workers to enter) or raise it by removing inexpert tasks and leaving a more demanding residual bundle. This expertise redundancy channel means that automation can redistribute opportunity even when it raises productivity, because it expands the set of workers who can meet the threshold. That way it can increase competition among incumbents and pressure wages. On the other hand, if it tightens the threshold, it can restrict entry and raise wages for a smaller set of qualified workers.

Task quantity versus task expertise

The authors distinguish task quantity (how much work an occupation does) from task expertise (how demanding the remaining tasks are). Task quantity behaves like a demand shift. When an occupation gains tasks, demand for its labour tends to rises. When it loses tasks, demand tends to fall. Task expertise behaves like a supply shift because rising expertise requirements shrink the pool of qualified workers. This yields a key prediction. Namely, occupations that become more expert-driven may see higher wages but lower employment, while occupations that become less expert-driven may see lower wages but higher employment. The prediction matters for interpreting AI. The same automation shock can increase pay in a role while reducing the number of employees (think of architects, many of whose low-level tasks have been automated) or expand them in a role while compressing pay and making work more standardized (think of taxi-drivers, whose special knowledge of a city geography has been replaced by GPS systems).

Routine-task automation and bifurcation

Using task data over 1977–2018, Autor and Thompson document a major compositional shift: routine tasks account for a large share of tasks removed, while abstract tasks account for most tasks added. Their summary statistics make the asymmetry very clear, roughly two-thirds of tasks removed were routine, whereas most tasks added were abstract. The crucial point is that routine tasks are not uniformly low skill. In some occupations they embody a high level of expertise (for example, specialized procedures and rule-bound decision tasks), while in others they are supporting tasks around a more expert core. Therefore, routine-task automation should bifurcate outcomes across routine-intensive jobs. The authors built a predictor based on 1977 task content that captures whether removing routine tasks would lower or raise an occupation’s expertise threshold. Occupations exposed to predicted expertise loss experienced declines in task expertise and wages, while those exposed to predicted expertise gain experienced increases in task expertise and wages. Also, in line with the model, rising expertise is also associated with relative employment decline. Quantitatively, they show routine tasks falling from roughly half of tasks in 1977 to under one-third by 2018, and they estimate that about 66% of tasks removed were routine while only around 17% of tasks added were routine. Abstract tasks constituted roughly three-quarters of tasks added. These descriptive patterns in their work suggest that many AI-exposed occupations will not share the same wage or employment trajectory.

Human agency and uneven adoption

Technical feasibility is not the only element needed to forecast labour-market change. Human preferences and agency will be crucial to understand the evolution in the coming years. Shao et al. (2025) built a large database, WORKBank (844 tasks, 104 occupations) and rated tasks on a Human Agency Scale using worker surveys and expert assessments. Workers express positive attitudes toward automation for a substantial share of tasks (about 46% on their measure), but agreement between workers and experts on the appropriate level of agency is low (around 27%), with workers tending to prefer more human control. The implication is that adoption will be a bumpy road. Even where an AI agent could technically perform a task, organizations may still choose human-in-the-loop designs because of accountability, safety, or perceived meaning of the work. Conversely, workers may welcome automation of unpleasant or repetitive tasks that experts view as hard to automate safely.

Implications

Together, the papers reviewed so far imply that the labour market will not simply have uniform upskilling. Instead, AI will reshuffle expertise thresholds. Some roles will become more expert-focused, better paid, and harder to enter. Others will become less expert-focused, and easier to enter. In addition, the speed and direction of change will depend on how workplaces allocate responsibility for AI outputs, including oversight, auditing, and error management. These agency tasks are likely to expand precisely where AI is most useful, creating new demand for workers who can validate outputs, design workflows, and communicate uncertainty in high-stakes settings. They further note misalignment in innovation incentives. Mapping a sample of AI-agent startups onto the desire–feasibility space, about 41% fall into low-priority or red-light regions, which could slow high-value adoption.

Early career access and the scarcity of traineeships

You may have heard from young people in the last two years about their increasing difficulties of lining up internships and traineeships. These stories are more than anecdotes. Hosseini and Lichtinger (2025) show that generative AI is driving what could be called seniority-biased technical change. They identify firm adoption using postings for GenAI integrator roles and track employment by seniority using large-scale résumé and vacancy data. In their event-study estimates, junior employment falls after adoption and reaches close to ten percent reduction within about two years, while senior employment is comparatively stable. Their triple-difference specifications reinforce the evidence on timing. The effects are small before widespread GenAI diffusion and then decline sharply in the period when generative AI adoption accelerates.

The mechanism is mainly reduced junior hiring rather than spikes in separations. This is consistent with career-ladder compression. Entry roles often involve bounded cognitive tasks that are increasingly automatable or compressible (drafting, analysis that can be easily put in a template, routine coding, and document review). Even if AI raises the productivity of individual juniors, the equilibrium number of junior roles can still fall if the volume of junior-suitable tasks declines. The result is fewer paid learning opportunities and a harder transition from education into work.

Hosseini and Lichtinger (2025) also highlight an intertemporal channel for labour impacts. If firms expect entry-level tasks to become automated soon, they may delay hiring to avoid future redundancy and adjustment costs, shifting attention from layoffs to missing first jobs. In distributional terms, it raises the stakes for education quality, signalling, and access to networks. This is very worrying, because those advantages are not evenly distributed, and it may explain the explosion of private universities that emphasize precisely those points in Spain. It also makes early-career policy and curriculum design central parts of an inclusive AI transition.

Opportunities for AI in improving education: Scaling real-time expertise

The previous studies discussed highlight the importance of education in the AI transition. The question is if AI can also help to modernize education. Wang et al. (2025) give a positive answer to the question. They provide causal evidence that AI can improve education when it scales expert practices rather than by replacing instructors. They introduce Tutor CoPilot, which offers real-time suggestions to tutors during live sessions. In a preregistered randomised controlled trial in an in-school virtual maths tutoring programme serving Title I (underprivileged) students, access to CoPilot increased topic mastery by about four percentage points on an intent-to-treat basis. There were larger gains, of about nine percentage points, for initially lower-rated tutors.

Message-level analyses indicate that CoPilot changes pedagogy, not just speed. Treated tutors were more likely to use high-quality strategies associated with deeper learning. For example, by asking guiding questions and giving steps to student reasoning, they were less likely to simply provide answers. The intervention therefore functions like coaching embedded into practice. It helps tutors adopt expert-like moves when they matter. And it is easily scalable.

This is good news for labour-market access given previous discussion. If firms supply fewer traineeships, education and training systems must deliver more feedback and guided practice before labour-market entry. AI systems that embed expert guidance into real activity can help students reach competence earlier and can support reskilling later in life. The paper’s cost discussion strengthens this point, contrasting the high expense of conventional professional development with an estimated marginal cost on the order of tens of dollars per tutor per year in their setting.

Challenges for economics education and what to do about them

These findings have implications for education in the field of economics. Oschinski et al. (2025) argue that Economics education must adapt quickly because Economics graduates enter jobs with high AI exposure and changing skill demands. Analysing shifts in job-skill requirements between 2015 and 2023, they report declining importance of some finance- and accounting-specific software skills and rising importance of statistical software, writing/editing, and analytical skills. They also highlight movement from traditional management skills toward project management and policy analysis. The broad message is that economics programmes should teach modern empirical workflows and communication, not only disciplinary theory.

These shifts imply that curricula must be designed with complementarity in mind. If AI can generate plausible drafts of text, code, and routine analysis, student assessment cannot focus on simple routine tasks. Instead, we should move urgently to test capabilities that make AI use reliable. For example, problem formulation, the logic of identification and inference, robustness checks, examining the provenance of data, or communicating transparently uncertainty.

In practice, this means we must include more project-based empirical work with replication packages, oral defences, in-class data exercises, and explicit instruction in AI literacy and verification. Students should practise using AI tools to accelerate drafts while being graded on the quality of judgement they apply to verify, contextualise, and improve those drafts.

Economics education is also a case where Shao et al.’s (2025) agency lens is directly relevant. Graduates will be expected to supervise AI tools and remain accountable for outputs in policy and business settings. Teaching should therefore cover when AI assistance is appropriate, how to document verification steps, and how to manage risks such as hallucination, biased data, and overconfident reporting.

And whereas Oschinski et al. (2025) is based on Economics training, many of these insights are likely to replicate well in other fields.

Implications for Spain

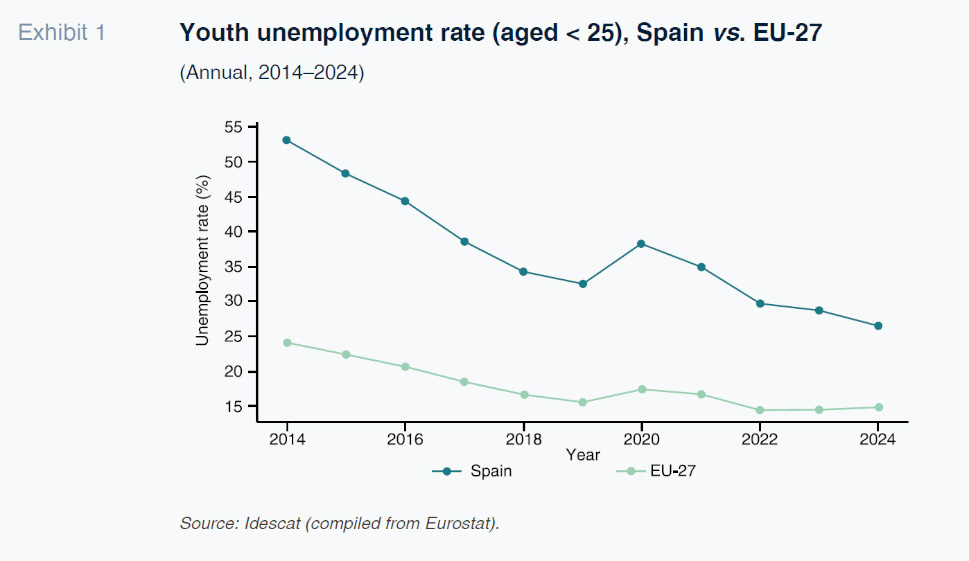

Spain’s context makes early-career access especially relevant. As Exhibit 1 shows, youth unemployment is consistently much higher in Spain than in other European countries. Even today, when economic conditions are very good, youth-labour reporting summarizing the Labour Force Survey (EPA) indicates an under-25 unemployment rate of 25.42% in Q3 2025 (INJUVE, 2025). When baseline entry conditions are weak, reductions in junior hiring associated with AI adoption can have amplified welfare costs by delaying the transition into stable careers and extending scarring effects.

Two priorities follow from the evidence. First, we need to strengthen apprenticeships and traineeships, so career ladders remain climbable, potentially through incentives tied to accredited training plans and employer reporting on progression outcomes. Second, we need to expand training capacity by using AI to scale feedback and coaching in vocational education and universities. Spain’s ongoing vocational education training (VET) modernization efforts (Bentolila

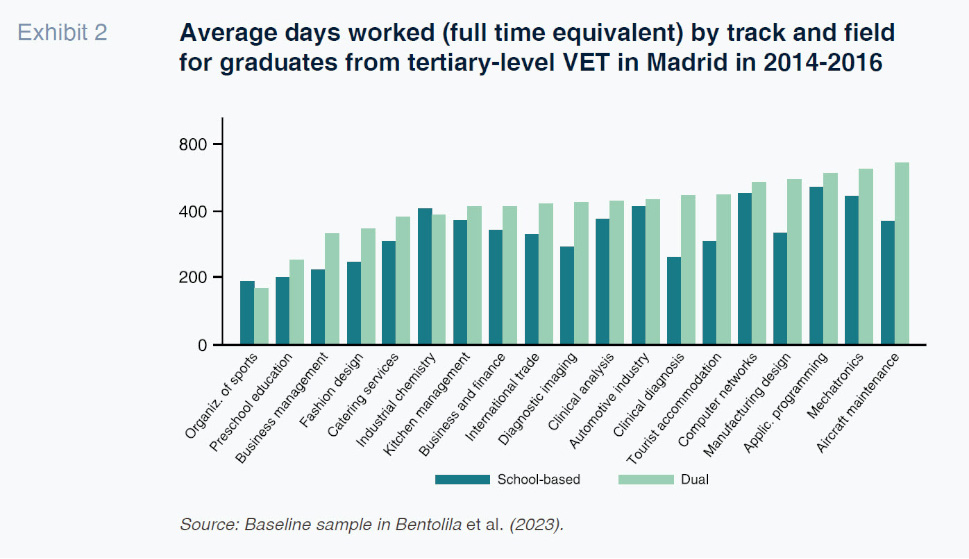

et al., 2020, 2023) provide an institutional route to deploy AI-enabled tutoring and coaching tools that raise the quality of instruction at scale. Specifically, Exhibit 2 shows descriptive statistics for the differences in employment between school based and dual VET. Bentolila

et al. (2023) show there are also causal differences using an instrumental variables (IV) distance estimator. Dual education, at all levels, including university, provides a proven template to the challenge created by the lack of internships.

A practical approach is to integrate AI-supported feedback into work-based learning: for example, tutors, mentors, or supervisors could use co-pilot style tools to standardise high-quality coaching, while assessment focuses on demonstrated competencies and verified outputs. Given Spain’s many SMEs, sectoral partnerships could pool resources for shared AI-enabled training.

Finally, Spain should evaluate these interventions using pilots and clear metrics on progression from training into stable employment. Embedding safeguards, like documentation, human accountability, and auditing in sensitive applications can align adoption with worker preferences for agency and can increase trust.

The final implication is curricular. Spanish Economics and Business programs can improve graduates’ prospects by embedding dual training, AI literacy, verification, and applied project work into core courses. In labour markets where entry jobs may be fewer but more demanding, the quality and credibility of demonstrated skills at graduation becomes an even more important determinant of access.

Conclusion

AI will reshape work by re-bundling tasks and shifting expertise thresholds. Autor and Thompson (2025) show why this can produce bifurcation, as some roles become more expert and harder to enter, and others less expert and more commodified. Shao et al. (2025) show that adoption depends on human agency and governance as much as on capability. These perspectives imply uneven change and a growing premium on oversight, verification, and responsibility.

Hosseini and Lichtinger (2025) provide early evidence that generative AI adoption is associated with reduced junior employment driven mainly by slower hiring, implying scarcer traineeships and tougher school-to-work transitions. Education is therefore pivotal. Wang et al. (2025) demonstrate that Human–AI systems can scale real-time expertise and improve learning at low cost, while Oschinski et al. (2025) outline how economics education can respond by embedding AI literacy and shifting assessment toward judgement, reproducibility, and communication. For Spain, where youth unemployment remains elevated, an inclusive AI transition will depend on maintaining pathways into work while upgrading training so new entrants can meet higher initial thresholds and to better support mobility throughout the life course. The current success of VET can serve as a template for making this feasible.

References

AUTOR, D., & THOMPSON, N. (2025). Expertise. Journal of the European Economic Association, 23(4), 1203–1271.

BENTOLILA, S., CABRALES, A., & JANSEN, M. (2020). ¿Qué empresas participan en la formación profesional dual? Papeles de Economía Española, 166, 94-104.

BENTOLILA, S., CABRALES, A., & JANSEN, M. (2023). Does Dual Vocational Education and Training Pay Off?

HOSSEINI, S. M., & LICHTINGER, G. (2025). Generative AI as seniority-biased technical change: Evidence from U.S. résumé and job posting data. Working paper.

INSTITUTO DE LA JUVENTUD (INJUVE). (2025). Jóvenes en la EPA. Tercer Trimestre 2025. Madrid: INJUVE. (Statistical summary based on INE EPA microdata).

OECD. (2025). OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2025. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OSCHINSKI, M., SPIELMANN, C., & SUBBU-RATHINAM, S. (2025). AI and the future of work for economists: Rethinking economics education. Discussion Paper, 25/788, University of Bristol.

SHAO, Y., ET AL. (2025). The future of work with AI agents: Auditing human agency, worker desires, and feasibility across tasks. Working paper.

WANG, R. E., RIBEIRO, A. T., ROBINSON, C. D., LOEB, S., & DEMSZKY, D. (2025). Tutor CoPilot: A Human–AI approach for scaling real-time expertise. arXiv preprint.

Antonio Cabrales. Universidad Carlos III