AI´s impact on productivity and market dynamics

Artificial intelligence promises major efficiency gains but may also reinforce industrial concentration, labour market polarization, and stock market overvaluation. The current AI-driven market boom raises questions about the growing disconnect between technological expectations and real-economy fundamentals.

Abstract: Artificial intelligence is emerging as a structural force with heterogeneous effects on productivity, employment, and stock market valuation. Estimates suggest a potential global GDP increase of around 14% by 2030, yet productivity gains remain limited by slow diffusion, uneven adoption, and organizational frictions, with most firms still failing to extract measurable returns from AI investment. At the same time, AI tends to reinforce industrial concentration and labour market polarization, as exposure to automation varies sharply across occupations and countries. Financial markets have moved far faster than the real economy: As of 2025, seven companies account for 35% of S&P 500 capitalization, and equity valuations have reached levels close to historic extremes. This divergence reflects strong expectations of future AI-driven profitability, amplified by abundant global liquidity and speculative dynamics. Whether current valuations can be sustained will depend on the timing and magnitude of realized productivity gains, as well as on how AI reshapes competition, capital allocation, and income distribution.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged in the last decade as a disruptive technology with profound economic implications. Its rapid advancement—exemplified by deep learning systems and generative tools such as large language models—has generated both excitement and concern. On the one hand, AI is expected to boost productivity, accelerate global growth, and increase incomes, just as other widespread technologies (electricity, computing, the internet) did in their time. But on the other hand, there are fears that it could replace jobs and deepen economic and social inequalities. The net impact is difficult to predict, as AI will be deployed in complex ways across the economy. Even so, there is consensus that we are facing a new technological revolution with potentially transformative macroeconomic effects.

Currently, the "fever" for AI is evident in both business investment and financial markets. The rapid spread of applications such as ChatGPT since 2022 has popularized the debate on the automation of cognitive tasks, not just manual or routine ones. Companies in multiple sectors are experimenting with AI to optimize processes, improve decision-making, or reduce costs. At the same time, investors have raised the valuations of AI-related technology companies to historically high levels, anticipating extraordinary future profits. This situation raises the paradox of a real economy that does not yet fully reflect the promises of AI, compared to markets that act as if the productive future were already guaranteed. This article rigorously but accessibly analyzes the implications of AI in four interrelated economic dimensions: productivity and growth; employment and inequality (including industrial concentration); and the relationship between AI and financial markets, particularly the possibility of overvaluation disconnected from the real economy.

Impact on productivity and growth

One of the main channels through which AI can transform the macroeconomy is productivity. Productivity—the amount of output obtained per unit of factor, whether labor or capital—is the fundamental driver of long-term economic growth and improved living standards. However, in recent decades, productivity has grown at a disappointingly low rate in many advanced economies. For example, in the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Spain, the cumulative rate of change in total factor productivity between 2013 and 2019 was below 2.5%. This phenomenon has led some economists to wonder whether AI could be the innovation that revives the rate of productivity growth. There are optimistic arguments that see AI as a technological change comparable to the steam engine or electricity, capable of generating significant increases in output per worker/unit of capital invested. These analyses point out that AI, as a general-purpose technology, could automate a large fraction of tasks in almost all sectors, greatly increasing efficiency. Unlike previous waves of automation focused on routine tasks, today’s AI (especially generative AI) has the potential to complement or replace complex cognitive tasks, allowing many workers to devote more time to creative or higher value-added work. In the most promising scenario, this would lead not only to higher productivity, but also to a permanently higher growth rate, as AI drives innovation in scientific research, new product development, and continuous improvements in production processes.

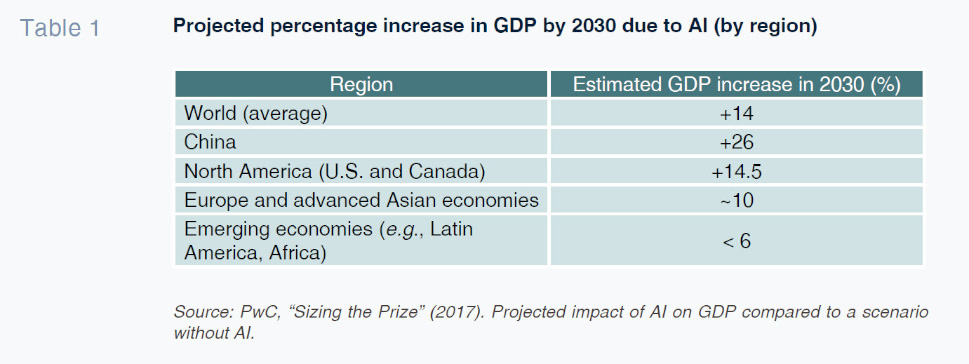

However, there is another line of analysis that is more cautious and suggests that the effects of AI on productivity could be gradual and modest. Acemoglu and Restrepo (2019) warned that many optimistic forecasts may overestimate the short-term impact. In fact, several reports have predicted that AI will boost economic growth by up to 5% per year in economies such as the United States, but Acemoglu (2024) points out that even revolutionary technologies of the past (such as electricity) took decades to become fully widespread. In any case, as Chaar et al. (2025) indicate in an OECD study, the impact of AI on productivity is expected to be heterogeneous across countries. In general, emerging economies risk benefiting less from AI due to the low incidence of knowledge-intensive services, where the gains from AI are mainly concentrated. Table 1 shows a compilation of GDP growth estimates compiled by PwC. A crucial factor in explaining why productivity does not yet fully reflect the rise of AI is the slow and uneven diffusion of these technologies in businesses. Although there has been an explosion of interest in generative AI since 2022-2023, the reality is that few companies have successfully integrated AI into their core business functions.

According to Nygaard et al. (2025), 95% of companies do not see significant returns on their substantial investments in AI because they have not been able to effectively implement the models in their daily operations. This study highlights the gap between technical potential and practical adoption: in information-intensive sectors such as finance and insurance, only about 10% of companies use generative AI, and even in the information technology sector, which is at the forefront of digitization, adoption was around 25% of companies by 2023.

Furthermore, according to the OECD (2024), in 2019 only 0.34% of the workforce had AI skills, reflecting the shortage of personnel trained to deploy these tools. All these indicators suggest that we are still in the early stages. It is also important to distinguish what type of AI applications are being implemented, as this determines their effect on productivity. Uses of AI that simply automate existing tasks can lead to incremental, sometimes disappointing, efficiency gains. Acemoglu and Restrepo (2019) call this "so-so automation": cases where a machine replaces a worker, but the increase in production is minimal. One example cited is self-checkout machines in supermarkets, which replace some cashiers but do not substantially reduce costs or prices (the customer does the employee’s job, but the store does not sell more groceries as a result).

Similarly, the technological waves of the late 20th century (computing, the internet) eliminated routine administrative jobs, but created professions that did not previously exist (programmers, data analysts, network technicians, etc.). The creation of new tasks was the mechanism that sustained employment and wage growth for much of the 20th century. With AI, new jobs will be created, but whether this will significantly replace previous jobs is more doubtful. According to the OECD, macro data could continue to show mediocre growth of around 1% per year in the productivity of advanced economies, prolonging the recent trend.

In the alternative, more optimistic scenario, AI is adopted in a more complementary way, freeing workers from certain tasks and pushing them toward creative, problem-solving, or high-value human interaction tasks. Under this scenario, AI would truly become the catalyst for a new productive revolution, in which, in addition to doing the same things faster, entirely new things would be done. It is plausible that reality contains elements of both paths. For now, the evidence suggests that the big leaps in productivity from AI are yet to come, and that achieving them will require reorganizing processes, training specialized human capital, and accumulating knowledge about how AI can transform business models.

Employment, inequality, and industrial concentration

The impact of AI on the labor market is the subject of intense debate. Unlike previous automations focused on manual or routine tasks, modern AI has the ability to also affect cognitive and highly skilled occupations, which broadens its disruptive reach. An analysis by the International Monetary Fund (2025) estimates that nearly 40% of global employment is exposed to AI in some way, a percentage that rises to 60% in advanced economies. This is because machine learning algorithms and generative systems can take on tasks that were previously performed by professionals, from writing text or code to analyzing medical images. However, exposure does not equate to complete replacement or dislocation: of the total number of jobs exposed, approximately half could benefit from AI as a complement (i.e., AI tools would increase human worker productivity), while the other half corresponds to jobs where AI could perform a substantial portion of current tasks, reducing the need for human labor. In extreme cases, some of these jobs could disappear or be radically transformed if task automation reaches its limit. This duality explains how AI can simultaneously increase efficiency and displace jobs, depending on the type of tasks that predominate in each occupation.

Regarding technological unemployment figures, it is important to note that so far there has been no wave of mass layoffs attributable to AI. In fact, initial data suggest that at this early stage, AI may be creating as many or more jobs than it destroys. This indicates that many companies are hiring AI specialists, data engineers, or other professionals to implement and manage these new tools, offsetting cuts in other areas. However, these figures are still quite small. According to an OECD report (OECD, 2023), despite the rapid growth in demand for AI skills, online vacancies in advanced countries related to AI accounted for less than 1% of all job offers in the period 2019-2022. This finding partly alleviates immediate fears of mass unemployment, but it does not guarantee that the balance will not tip toward net job losses in the future. Much will depend on the pace of adoption and the ability of technology to replace tasks entirely. Benchmark studies such as OpenAI (2023) have estimated that about 19% of workers have at least half of their tasks susceptible to automation by AI. However, it should also be noted that a job is more than the sum of individual tasks: it involves social skills, judgment, adaptability, and versatility. Therefore, having 50% of tasks "exposed" does not mean that the occupation will disappear, but rather that its tasks will evolve. The challenge lies in how job roles will be reconfigured: if AI takes over the routine part, workers can focus on the creative or relational aspects, making their work more productive; but if AI ends up taking over even the core tasks, the job could disappear.

From a historical perspective, the advent of AI reignites the old debate between techno-optimists (who believe that technology creates more jobs than it destroys) and techno-pessimists (who predict structural unemployment). AI could deepen this polarization, as it automates both routine and some non-routine tasks that previously protected mid-level professionals. This raises the risk of a widening gap between highly skilled workers (able to leverage AI) and the rest. As the IMF (2025) points out, AI is likely to increase income inequality in most scenarios if no action is taken: workers complemented by AI will see their productivity and wages rise, while those displaced or unable to adapt will see their incomes stagnate or fall. In addition, returns on capital could increase in companies that successfully adopt AI, disproportionately benefiting owners and shareholders (who are typically concentrated in the upper income strata). This set of factors suggests a trend toward greater income concentration: countries and individuals with more resources to invest in AI may reap most of the gains, widening existing gaps.

One area where the influence of AI is very palpable is in industrial structure and market competition. In recent decades, many advanced economies have experienced increased industrial concentration, meaning that a larger share of the market is captured by the leading companies in each sector. This phenomenon of "superstar companies" has coincided with the era of digitalization and globalization, during which companies such as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have become dominant. The introduction of AI could further reinforce this trend if only a few players are able to exploit its full potential. In a plausible scenario, only the largest companies can afford the massive investment in computing and data required to develop advanced AI, giving them an insurmountable advantage over smaller competitors. Even today, training a state-of-the-art model requires enormous resources: for example, training the GPT-4 model costs around $100 million, and running it operationally involves around $700,000 per day in computing expenses. However, the example of DeepSeek, which has achieved performance similar to ChatGPT with only $5.6 million in development costs, could open the door to accelerated democratization of generative AI.

[1] In any case, as long as performance improvements continue to be associated with larger and more expensive models, only corporations with multimillion-dollar budgets will be able to lead the technological frontier. The global technology sector is dominated by just six large companies, which not only lead innovation but also "buy out their competitors and limit innovation" by others. This non-creative concentration—where competition is eliminated through acquisitions—may lead to less dynamism in the long term, as dominant firms may lack incentives to fully deploy technologies that cannibalize their existing business models.

However, a future of greater technological concentration is not inevitable. Several analysts propose an alternative scenario in which AI is democratized. For example, the proliferation of open-source AI models (such as certain models released by Meta or academic communities) could allow medium-sized and even small companies to access cutting-edge AI tools without incurring the enormous costs of developing them from scratch. If this open ecosystem flourishes, many companies could implement AI tailored to their niche markets, reducing the gap between giants and entrepreneurs (IMF, 2025).

AI and financial overvaluation: Disconnect between the real economy and markets

The euphoria surrounding AI has not only permeated economic discourse but has also driven a spectacular rally in the stock markets, especially in technology stocks. Many investors, anticipating that AI will trigger huge increases in future profitability, have pushed the share prices of companies linked to this technology to very high levels. This has raised concerns about a possible "AI bubble" in financial markets, characterized by valuations that are disconnected from the current fundamentals of the real economy.

A glance at market indicators reflects this dynamic. By the end of 2025, iconic companies of the AI era had reached unprecedented market capitalizations: for example, Nvidia key manufacturer of chips for AI computing—briefly became the world’s most valuable company, with a market value of around $4.5 trillion, surpassing even Apple and Microsoft (the latter two hovering around $3.9 trillion each). This company’s market capitalization currently accounts for almost 4% of global GDP and 16% of U.S. GDP.

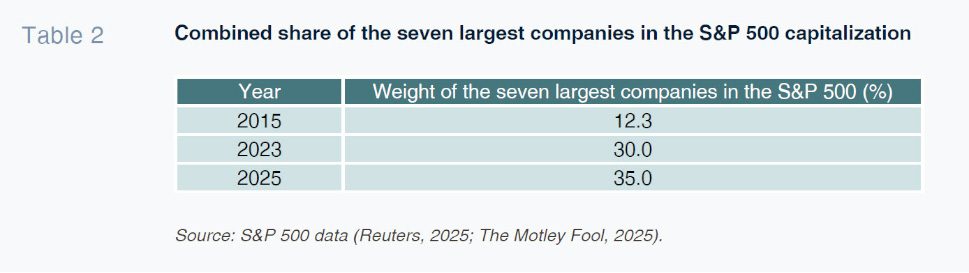

[2] Historically, no company has ever had such a significant weight in the global and American economies. In addition, collectively, the 10 largest listed companies (almost all in the technology-digital sector) came to represent more than a third of the total value of the S&P 500 index, the highest level of stock market concentration in more than 60 years (Table 2). To put this phenomenon into perspective: Nvidia alone accounted for around 8% of the S&P 500, and the so-called Big Tech companies (Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet/Google, Meta) plus a few associates (Tesla, Nvidia) formed the core of the market, accounting for most of the index’s gains in 2023-2024. This situation is reminiscent of other phases of irrational exuberance and raises the question of whether current prices can be sustained if reality ultimately fails to meet high expectations.

The "Magnificent Seven" (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta, and Tesla) went from accounting for 12% of the index in 2015 to approximately one-third in 2023, reaching 35% in 2025 (Table 2), reflecting a market highly concentrated in a few winning companies of the digital age. In fact, the global capitalization of these seven companies has exceeded the aggregate GDP of the European Union.

[3] This concentration implies greater market vulnerability: if only one or two of these leading stocks were to suffer a significant correction, they would drag down the entire index.

The high stock prices of technology companies suggest that the market is incorporating expectations of extraordinary future profits thanks to AI. However, these forecasts may clash with the reality of the productive economy, at least in the short and medium term. While stock prices soared in 2023-2024, the global economy faced modest growth and persistent uncertainties: episodes of inflation that forced interest rate hikes, cooling demand in several countries, and even heightened geopolitical risks. Normally, higher interest rates and signs of economic slowdown would put the brakes on the stock markets, but the effect of AI has counteracted these factors. This led to a notable disconnect between the markets and the real economy: on the one hand, financial markets anticipating a jump in productivity and profits thanks to AI; on the other, productivity and growth data that do not yet show that jump.

One indicator that illustrates this disconnect is the relative valuation of the stock market. Shiller’s CAPE ratio (price divided by 10-year average real earnings) for the S&P 500 reached levels close to 40 in 2025, one of the highest in the last 140 years, only marginally surpassed by the peak of the dot-com bubble in 1999-2000. This implies that investors are paying $40 for every dollar of average cyclically adjusted earnings, a sign of extreme optimism about the future. Using the traditional P/E ratio (price to current earnings), the valuation is also around the 95th percentile historically, i.e., in the top 5% of how expensive the market has been.

Why might investors be overestimating the economic impact of AI? One possibility is that there is a time lag: markets anticipate (perhaps rightly) that AI will transform the economy but underestimate the timeframe and difficulties of that transformation. As discussed, integrating AI involves organizational changes, investment in human capital, and overcoming technical challenges. Substantial gains for corporate profits may come, but later than the financial hype suggests. Another possibility is the classic speculative dynamic: investors buy shares in AI-related companies not only for their fundamentals, but because they trust that other investors will buy them later at even higher prices, fueling a self-reinforcing cycle of increases (which defines a bubble). In 2023, there were striking examples, such as small companies adding "AI" to their names and seeing their share prices rise suddenly without any real changes in their business, reminiscent of episodes of speculative mania in the past.

It should be noted that, while there is some general overvaluation (as indicated by the low implied risk premium on equities, around only 2% in the U.S.), the market’s dependence on a few leading stocks makes the situation more fragile. By 2025, the bull market was largely sustained by the exceptional results of those five to seven giant companies. A significant stumble by any of the "magnificent seven" could trigger a proportionally large drop in the S&P 500 of around 10% or more, with a domino effect on confidence.

None of this means that the AI revolution will not generate real value for the economy and businesses. In fact, many of the promises may well be fulfilled in the long term: productivity gains, the creation of new markets, improved business margins and, ultimately, higher profits. Several tech giants are investing heavily in AI, and in some cases, we are already seeing improvements in operational efficiency or new related lines of business (e.g., AI-optimized cloud services, specialized chips sold at high margins, etc.). In other words, there are fundamentals that support some optimism. The problem lies in the timing and magnitude of the disconnect: markets seem to have "discounted" today’s benefits that may take a decade to materialize, and on a scale that is not guaranteed. If the real economy manages to live up to expectations—that is, if AI does indeed trigger a boom in productivity and corporate profits in the coming years—then current valuations could gradually be validated without a collapse through growth in the denominators (profits). Conversely, if improvements are more modest or slower, the correction will come through the numerator (prices), as stock market history has repeatedly shown.

Conclusions

The AI revolution presents a complex and nuanced picture for the macroeconomy and markets. In terms of productivity, AI promises efficiency improvements and possibly a new boost to long-term growth, but so far, its aggregate fruits have been limited and may take time to mature. Much will depend on whether we manage to orient the technology toward the creation of new tasks and complementarity with human labor, rather than reducing it to simplistic automation that generates non-creative destruction. In terms of employment and equality, AI has a dual nature: it can increase the productivity of many workers and generate new roles, but it also threatens to further polarize the labor market and concentrate the benefits among those who have the skills or capital to take advantage of it. This poses challenges in terms of adaptation, training, and policies to mitigate a "winner-takes-all" dynamic. Finally, in financial markets, AI has triggered a wave of optimism that has pushed valuations to historic highs, creating a gap with the real economy. This phenomenon reminds us of the risks of extrapolating the future without sufficient support in the present, while underscoring the enormous confidence (or speculation) placed in the potential of AI.

Notes

References

Funcas Finance and Digitalization Area