Snapshot of the Spanish banking sector

in a European context

The results of the latest round of EU-wide stress tests have reinforced the perception of improvement in the Spanish banking system, as well as of increased solvency. However, due to persistent doubts about some segments of the European financial system, these tests have failed to reduce investor uncertainty over the state of European banking to the extent desired.

Abstract: Since the beginning of 2016, financial markets have shown a generally negative trend with notable volatility. The banking sector has been among the hardest hit. In addition to the international macroeconomic difficulties at the start of 2016, other factors have generated uncertainty, such as Brexit or evidence of impairment of Italian bank assets. Negative interest rates have also created a tense financial environment in which the generation of profit margins and profitability is even more complicated, which has led most banking institutions to focus their efforts on improving efficiency –in tandem with solvency– so that their profitability is affected as little as possible. With the market situation and the sharp fall in interest rates in 2016, the six largest Spanish financial institutions in the first half of the year recorded combined net profit of 6,381 million euros, down 21.2% on the year-ago period. However, non-performing loans continued to fall, to stand at 9.48% at June 2016, and solvency increased by 0.6 percentage points from June 2015 to June 2016, with the CET1 ratio reaching 11.8%. The European Banking Authority (EBA) stress tests have consolidated the longer-term vision of the improvement in the Spanish banking sector’s solvency, although they have not been able to ascertain, to the extent that would have been desired, which banking sectors present the main problems and to what degree, with regard to both credit risk (e.g., Italy) and market risk (e.g., Germany).

A strained financial and macroeconomic environment

At the beginning of 2016 there was already a widespread expectation of a slowdown in the growth of the world economy, with uneven development in the case of Europe. In Spain, the macroeconomic outlook was, in general, revised upwards by the major analysts. The latest Funcas forecast panel from September 2016 gave a “consensus” GDP growth estimate for Spain of 3.1% this year. However, the outlook for 2017 remained at 2.3%, suggesting that the uncertainty and turbulence could cause problems next year.

Certain recent events in Europe and, overall, a growing perception of increased political risk have had a lot to do with this deterioration in the medium-term outlook. On July 19

th, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) also revised its global growth outlook

[1] alluding to some of these risks, in particular, pointing to the UK’s decision to leave the EU (Brexit), suggesting that “Before the June 23

rd vote in the United Kingdom in favour of leaving the European Union, economic data and financial market developments suggested that the global economy was evolving broadly as forecast (…). Growth in most advanced economies remained lacklustre, with low potential growth and a gradual closing of output gaps. Prospects remained diverse across emerging market and developing economies, with some improvement for a few large emerging markets –in particular Brazil and Russia– pointing to a modest upward revision to 2017 global growth relative to April’s forecast.” As a result, the IMF concluded that “The outcome of the UK vote, which surprised global financial markets, implies the materialisation of an important downside risk for the world economy. The global outlook for 2016-2017 has worsened, despite the better-than-expected performance in early 2016.”

Assessing the consequences of Brexit for the Spanish economy in general, and for its financial system in particular, requires a calm, comprehensive and individual effort to correctly assess the political outcomes that will determine its impact. However, it is hard to find anything positive to say about news that, almost in its entirety, is negative both for the UK and for the European Union and Spain. In the latter case, this is not only because of Spain’s trade surplus with the UK, but also because of the involvement of Spanish companies, in particular financial institutions, in the UK, among many other interactions that have to be considered.

In addition to the unexpected Brexit, there are other sources of economic and financial uncertainty with varying degrees of current and potential impact on the Spanish banking sector. Uncertainty persists over the short-term development and capacity of recovery of emerging economies that are particularly important for Spanish financial institutions, especially Brazil. This adds to the doubts that are still widespread regarding economies with significant potential global spill over effects such as China, with an uncontained credit bubble, growing problems with its trade balance, imbalance in its investments, and a very high degree of corporate leverage.

The response to this environment of prolonged uncertainty and growing European political risk continues to be largely a monetary one. The Bank of England reacted to Brexit with monetary stimuli and a historic interest rate cut. Meanwhile, the positions of the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve are ever more divergent, reflecting the different inflation and growth expectations on both sides of the Atlantic. In any case, the general discourse of the monetary authorities, especially in Europe, is that it is very difficult for them on their own to be the catalyst for solid and lasting growth. In any event, the European financial system is facing an unusual situation of negative real interest rates which, leaving aside the opportunity this presents in terms of liquidity, is creating major market distortions. Although these rates lighten the debt burden for a wide range of players, they hinder the establishment of prices and spreads in a large number of financial agreements.

Furthermore, the situation of Italy’s banks and the doubts as to the effectiveness of the measures that have been established to date are further specific sources of uncertainty for the financial system. There is also a widespread perception that the stress tests, the results of which were published by the EBA on July 29th, have not resolved the uncertainty about Italy’s banking sector or that of other countries such as Germany, where concerns remain with regard to the quality of assets in various aspects.

In this context, the European markets have had a markedly negative performance in 2016 to date, and the banking sector is among the hardest hit. The combination of growing uncertainty and historically low market interest rates has also been evidenced in the results of the Spanish financial institutions in the first half of the year. However, Spanish banks are increasing their level of solvency and have none of the doubts about the quality of their assets that continue to exist with respect to other EU countries. In any event, as has often happened in recent years, doubts about one part of the EU have a negative effect on the whole.

Bank results and loans in a context of negative interest rates

The situation of European banks in the first eight months of 2016 is influenced by market expectations regarding the value of assets and business prospects. In the case of Spain, although reporting transparency has greatly increased, doubts regarding some European banks extend to the current governance capacity of the banking union and to the industry as a whole. However, perhaps adding further downward pressure on valuations are the negative interest rates and the discounted present value of events, such as Brexit or the expected weakening of the global economy. Taken together, these factors represent the major challenge faced by the banks internationally regarding their profitability.

Even before entering the negative interest rate environment, the pressure on net interest income was considerable because global, and in particular European, banking was showing clear symptoms of oversupply and the need for restructuring. The negative interest rates, in addition, have not been accompanied by an increase in demand for financing, since this demand –and also, to some extent, supply– is shaped by still high levels of private sector debt in many countries. Also, there is no “natural” connection between interest rate levels and the level of solvency of demand for loans because these low interest rates are not caused by an interaction between this demand and supply but rather by an exceptionally expansionary monetary policy. Under these conditions, it is not surprising that, even in countries like Spain where there has been significant progress in bank restructuring, financial institutions continue to plan a reduction in offices and employees to bring supply in line with demand and to reduce costs to offset the reduction of income.

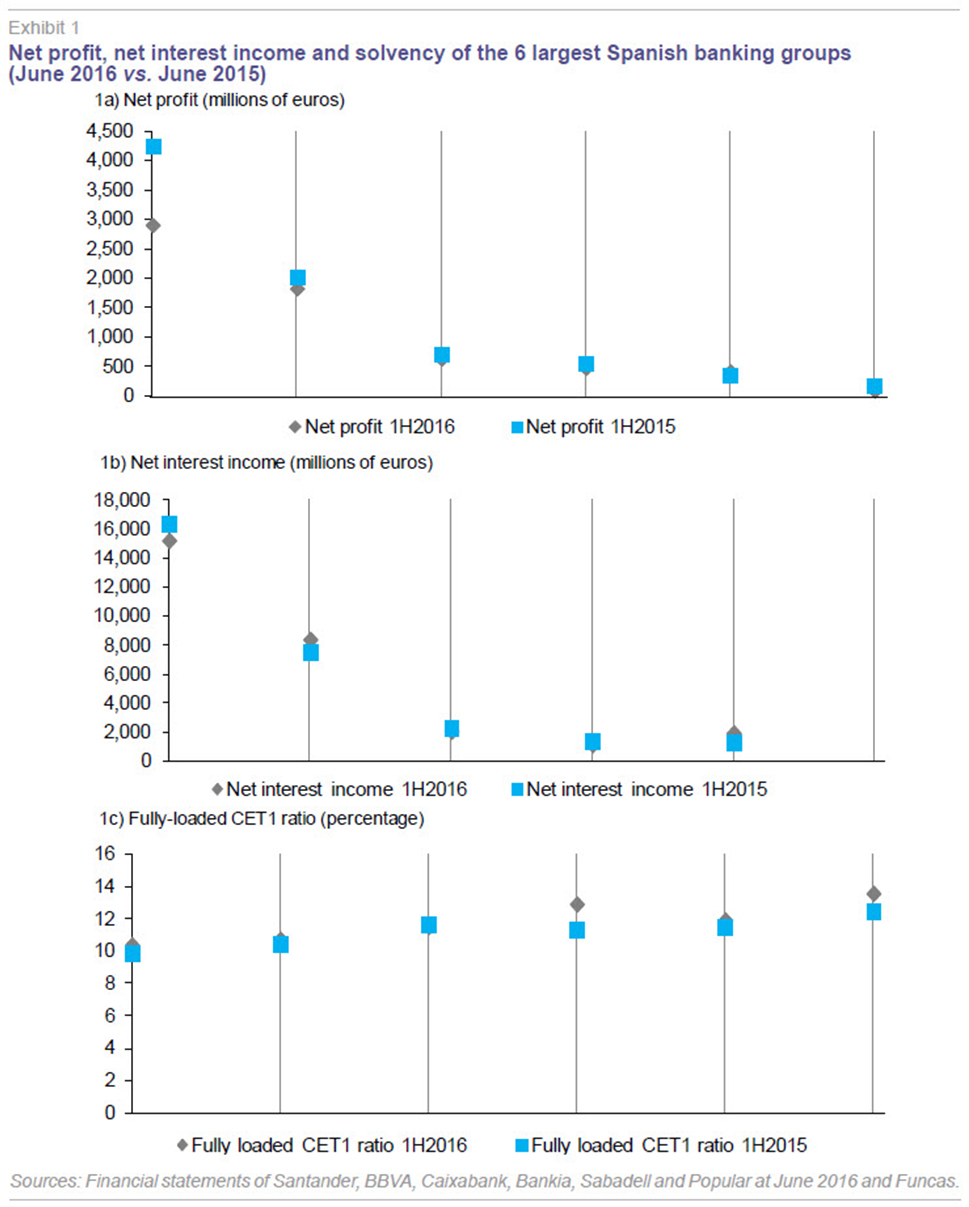

The results of the big Spanish banks and their solvency levels in the first half of 2016 compared to the same period in 2015 (Exhibit 1) illustrate these tendencies. Net profit has fallen year-on-year in most cases. The six largest institutions generated attributable profit of 6,381 million euros in the first six months, down 21.2% on the first half of 2015. Similarly, net interest margin declined in the same period by 1.5% to 30,176 million euros in the first six months of 2016. This tough market environment, however, has not prevented an increase in solvency (according to the fully-loaded CET1 ratio envisaged by the Basel III requirements) from an average of 11.2% in June 2015 to 11.8% in June 2016.

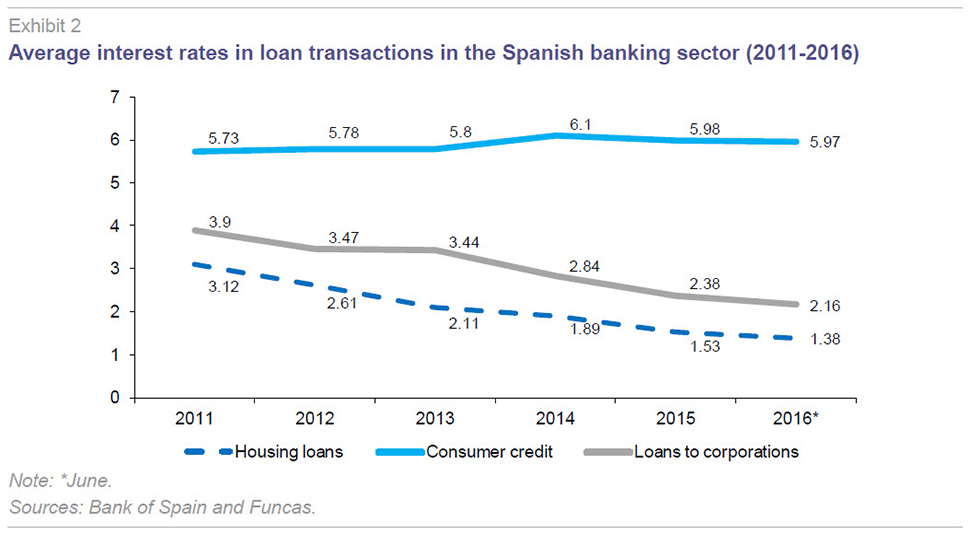

The sequence of events mentioned above, which has added to market uncertainty, caused the monetary authorities to redouble their efforts in 2016 to ensure an adequate provision of liquidity. This has resulted in lower interest rates in financing transactions. However, conditions of access via pricing do not necessarily concur with regulatory pressures and the solvency conditions of demand. Exhibit 2 shows the fall in average rates of loan supply, especially significant in housing loans and loans to corporations.

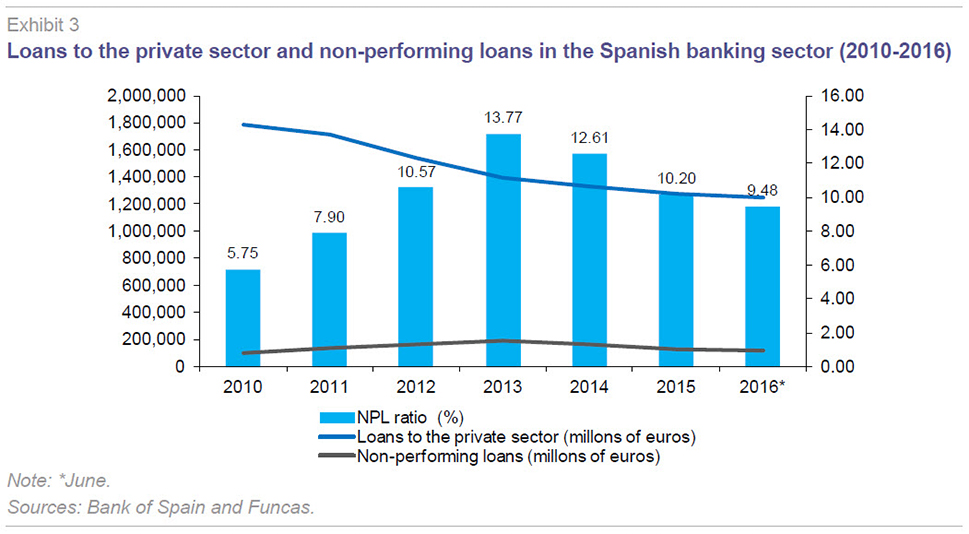

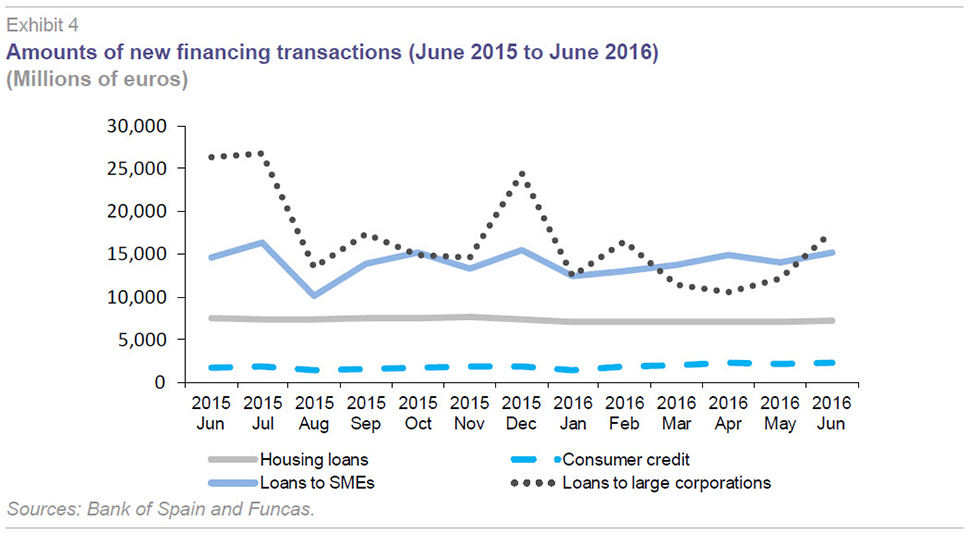

Are market conditions hampering the improvement in asset quality? This is not the case in the Spanish banking sector. As can be seen in Exhibit 3, the non-performing loan ratio is falling continuously, from 13.77% at 2013 year-end to 9.48% at June 2016. It is likely, in addition, that this reduction in problematic loans will accelerate as the ratio denominator, the balance of private sector loans, ceases to fall as it has done in recent years and starts to increase. This will be noticeable when debt repayments are overtaken by new financing flows. Specifically, loan flows are on the rise, as shown in Exhibit 4, although the change is more significant in loans to SMEs than in other segments.

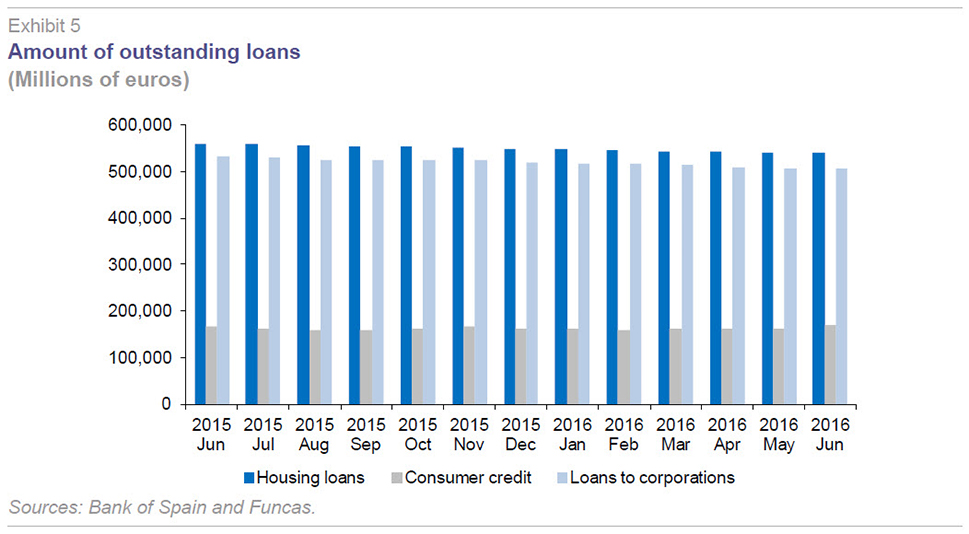

Outstanding loans (Exhibit 5) have continued to fall in the case of housing loans but, since February 2016, there has been an increase in consumer loans and, since June, an increase in the stock of loans to corporations.

Stress tests with an unequal impact

The European Banking Authority –in conjunction with the European Central Bank– presented on July 29th the results of the stress tests of 51 financial institutions, which account for around 70% of banking sector assets in the EU, including six Spanish banking groups. It should be noted that these tests were conducted in the midst of growing doubts and deep concern for the health of Italy’s banking sector, particularly focused on certain institutions such as Monte dei Paschi Di Siena, with a substantial increase in NPLs and poor medium-term macroeconomic and business prospects.

From the perspective of financial stability, the aim of these simulation exercises should be to increase transparency, identify weaknesses and direct possible courses of action. However, it is not clear that the July 2016 stress tests have had a significant informative effect that has boosted confidence in the European banking sector as a whole and in that of certain countries in particular.

At least three matters can be identified that detract from the value of the stress tests for instilling confidence. The tests were conducted with bank data of December 31st, 2015. While recognizing that all the applicable reporting requirements cannot provide an absolutely up-to-date picture, the 2015 year-end banking results help explain from where we have come more than to where we are going. The EBA itself has acknowledged that Europe is a little behind in these banking transparency and control exercises as compared to the United States.

In recent years, despite the advances in the banking union, problems of institutional cohesion have shown up that have meant that any effort to strengthen the European financial security network is fraught with problems. The banking union, as the main initiative, is one example. It is a union whose simple design and launch are extraordinary news but which, to be effective, needs a practical boost and some traction. Unfortunately, the current situation of some European financial systems (Italy, Germany) is not the best for the launch of single supervision, and this is generating significant reputational problems.

The Italian banking problem in particular presents certain weaknesses that are yet to be resolved, including most notably the following:

- The asset quality problems have been building up for years, without any action having been taken in this respect. Growth in NPLs is the clearest sign that not only has it not improved, but rather it continues to worsen.

- With NPL levels exceeding 20% –with wide variability above this percentage, depending on the estimates– it is not enough to focus supervision efforts on a single institution. The stress tests revealed the existence of 220,000 million of non-performing bank assets in Italy’s financial institutions.

- Italy’s banking problem is not liquidity –even less so with the financing possibilities currently offered by the ECB– but rather solvency and various European analysts estimate a wide discrepancy between the book value of assets and their market value, which could require a capital injection of at least 40,000 to 60,000 million euros.

- The Italian political and supervisory authorities have pointed to the effects of the economic recession on bank balance sheets. Even assuming that this were the main cause of the problem, most analysts estimate the growth of Italian GDP at around 1% per year for both this year and the next, with significant downside risks, suggesting also that the problem could spread. On this point, a good number of analysts have estimated that the adverse macroeconomic scenario envisaged for the Italian banking sector in the EBA tests was, at least comparatively, rather optimistic.

- An additional problem resides in the possible solution. Italy’s government and supervisory institutions claim to be able to resolve the problem without the intervention –whether financial or disciplinary– of the European single supervisor. Rescue by the Italian Treasury would mean that it would be the taxpayer (bail-out) and not the shareholder or bank bondholder (bail-in) that incurs the losses. However, it would mean making an exception with regard to the recently launched European rules governing the functioning of this single supervision. European governance is entering the choppy waters of exceptions and doubts and this also entails uncertainty for investors with regard to the current strength and cohesion of the banking union.

As for Germany, the stress tests have not lead to an appreciable reduction in doubts about the exposure to structured investments and derivatives of some institutions either. Certain German banks that are among the largest worldwide are listed on the markets with a 70% discount with respect to their book value and the credit default swaps are traded at similar rates to those at the time of maximum tension in the sovereign debt crisis. These seem to be sufficient grounds for concern. The July stress tests did indeed show a high market risk associated with investments in derivatives and other securities of these institutions.

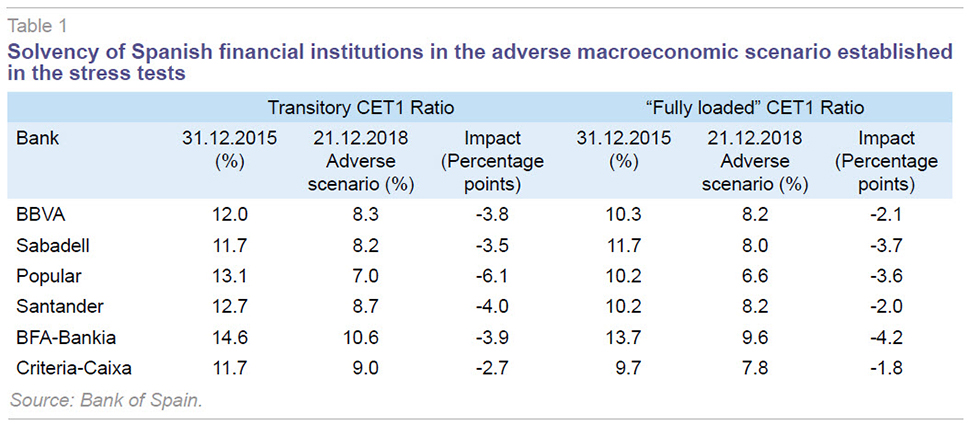

With this background for two of the most important European financial systems (Germany and Italy) and the apparent complacency with regard to the test results, financial institutions such as those of Spain have not been able to benefit to the extent that would have been desirable from their higher degree of transparency, soundness and recapitalization. Table 1 shows the estimated resistance of Spanish banks –in terms of capital consumed– in the adverse scenario of the EBA tests.

The Bank of Spain points to the positive aspects of these results of the Spanish banking sector, suggesting that

[2] “the results of the stress tests of Spanish institutions show an appreciable degree of resistance, comfortably exceeding the capital requirements used as reference in previous stress tests. A large portion of the estimated decline in most cases stems from the impact of the gradual elimination of the transitional arrangements of the solvency regulations in the three years of tests. Excluding the aforementioned effect, the impact of the tests is reduced significantly, as observed in the evolution of the fully-loaded ratio.”

As a whole, there appear to be two opposing forces with respect to the reporting value of the stress tests in reducing market uncertainty. On the one hand, some weaknesses were identified in certain countries in late 2015, many of which the very institutions affected are trying to resolve, mainly through capital increases. On the other hand, however, a certain unequal treatment can be discerned in the reporting requirements. In the past, countries such as Spain or Ireland offered a level of detail on the quality of their assets –and adopted measures proportionate to the problems detected– which no longer appears to be the case. It should also be noted that some of the bail-in measures put in place previously without the relevant regulatory framework are apparently being omitted in cases such as Italy, there now being a legal requirement at the European level for implementing them.

Regulatory and business outlook

This article has reviewed the main figures and ingredients of the complicated context in which European banks operate in 2016, paying special attention to Spanish financial institutions. The main conclusions from this analysis suggest that:

- Brexit and the solvency problems of Italy’s banking sector have added to the sources of financial and macroeconomic uncertainty already seen at the beginning of 2016.

- The negative real interest rates have added pressure to the already significant problems in increasing bank profitability and margins. The sources of uncertainty taken as a whole have had negative repercussions on the market value of European banks.

- The stress tests published by the EBA in July have not had a significant effect on reporting transparency that might have reduced investor doubts as to the state of European banking.

- The results of the EBA stress tests have reinforced the perception of improved quality of Spanish bank assets and increased solvency. In any event, these tests have not permitted a differentiation of the more solvent banking sectors from those showing more problems to the extent desired.

- Although loan access conditions have improved by means of pricing, negative interest rates are caused more by the action of an exceptionally expansionary monetary policy than by an increase in demand and its solvency.

Given these conditions, it can be expected that for the remainder of 2016, strategies geared towards restructuring will continue to be seen in the European banking sector. Insofar as the problems of Italian banks are resolved, there may be an improvement in market values. As for Spain, outstanding loans are beginning to show a timid but appreciable recovery, which illustrates that new financing transactions are starting to outstrip loan repayments. An acceleration in the fall in banking NPL rates in Spain can also be expected.

Notes

Santiago Carbó Valverde. Bangor Business School and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. Universidad de Granada and Funcas