Recent Spanish regulation aimed to improve SMEs’ access to finance

Recent regulations approved in Spain seek to improve SMEs’ access to both bank and alternative financial sources through reducing information asymmetries across borrowers. Although too early to assess the efficacy of the measures, they no doubt represent an important step forward towards increasing transparency of the SME credit risk assessment process.

Abstract: Despite recent improvement in SMEs’ access to finance in Europe as a whole, and in Spain in particular, small and medium size enterprises still face significant constraints. In Spain, this issue is of particular significant because i) SMEs’ comprise nearly 99.9% of the Spanish business landscape; and, ii) the drying up of credit experienced in Spain relative to that of neighbouring economies was more pronounced. Recent regulations approved in Spain aim to address some of the existing SME finance challenges by attempting to make bank finance more accessible and flexible, while at the same time increasing access to alternative financing sources, through the publication by finance providers of an SME Financial Information report – designed to reduce SME information asymmetries. The report contemplates various aspects of the borrower’s credit profile, with one of the most significant novelties being a borrower risk rating, comprised on the basis of both financial and qualitative variables. Additionally, the report provides information over the borrower’s relative position in the sector. Although the measures will not come into effect until October, these regulatory developments already undeniably mark a milestone in terms of the transparency of financial institutions’ decision-making process.

The agendas of the main economic authorities, in both Spain and Europe, and of the main international organisations

[1] have been focusing in recent years on the impact of the economic and financial crisis on the flow of financing to companies, particularly to small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), for whom, despite the improvement in the availability of credit in recent years, access to financing remains one of the biggest problems they face.

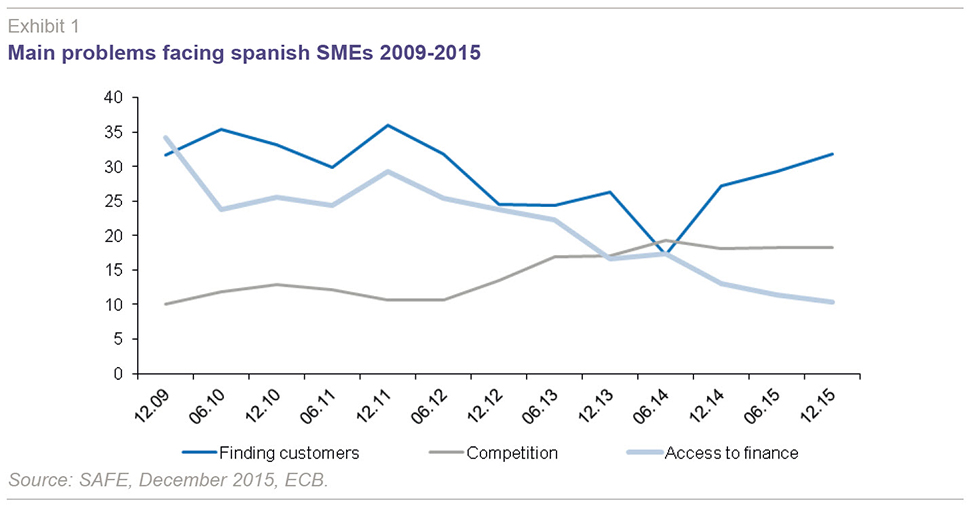

In Spain, if we extrapolate the trend in the figures shown in Exhibit 1, compiled from the ECB’s six-monthly

Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises [2] (SAFE), to the 3.2 million SMEs in existence at present,

[3] we see that indeed access to financing has been dissipating as a concern since 2009, as is evidenced in the summary of the most recent survey (April-September 2015) published in the Bank of Spain’s December 2015

Economic Bulletin:

“In short, the latest SAFE results evidence extension of the gradual improvement in access by Spanish SMEs to external financing between April and September 2015. Against the backdrop of gradual recovery in business volumes and their financial situation, these companies are perceiving increased bank willingness to lend them money, fewer difficulties in securing new funds and more favourable financing terms and conditions. In addition, on many of the aspects analysed, the improvement is being felt more robustly in Spain than in the EMU as a whole. Lastly, the survey also reveals positive expectations, with Spain’s SMEs expecting their access to bank credit to continue to improve between October 2015 and March 2016.”

This improvement does not, however, prevent access to financing from ranking sixth among these companies’ concerns (just below the issues related to the ‘cost of labour’, ‘availability of skilled labour’ and ‘regulation’), and as the top concern facing some 11% of these firms.

Regardless of this positive trend, the overwhelming predominance of SMEs in the Spanish business landscape – 99.9% –, coupled with the fact that they generate 66% of corporate jobs,

[4] is reason enough for any economic strategy tackling matters of social cohesion, innovation or job creation to address in parallel the development, diversification and upsizing of these companies (95.9% of Spain’s SMEs had less than nine employees at year-end 2014), to which end it is necessary to continue to improve their access to finance.

In order to facilitate this climate of credit normalcy, in recent years, the regulatory effort has taken two simultaneous directions: firstly, reforms designed to enhance the flow of bank credit and secondly, reforms aimed at diversifying SMEs’ financing options, mainly via the capital markets.

In Spain, Law 5/2015 (of April 27th, 2015), on the promotion of business financing, represents the Spanish law-makers’ response to the decrease in credit experienced in the early years of crisis following a period marked by a significant credit boom. The drying up of credit was, moreover, more pronounced in Spain than in neighbouring economies as a result of the deleveraging forced upon certain Spanish banks as part of far-reaching restructuring efforts undertaken to correct the imbalances accumulated in the past and, above all, the measures adopted in the wake of implementation of the Memorandum of Understanding entered into under the scope of the EU’s Financial Assistance programme.

With this in mind, the afore-mentioned piece of legislation marks a strategic shift in the legislation governing the various sources of financing available to the Spanish economy in an attempt to boost development of alternatives to bank financing while at the same time seeking to make bank financing more accessible and flexible, specifically by remedying, at least to a degree, the information gap between SMEs and finance providers believed to potentially impede and increase the cost of SME access to finance.

At the European level, the most ambitious initiative in this respect is the Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union,

[5] approved by the European Commission on September 30

th, 2015, which contemplates, among other actions, overcoming “information barriers that prevent SMEs and prospective investors from identifying funding or investment opportunities,” including through structuring “the feedback given by banks declining SME credit applications.” In addition, and in this same information-enhancing vein, the Commission wants to promote the exchange of best practices among EU member states such that SMEs seeking market-based financing can avail of efficient sources of information and support in all member states.

[6] Perhaps the time has come to add the Spanish model for

SME financial information, which is articulated around the

SME-Financial Information document – a standardised report assessing the creditworthiness of SMEs and their relative positioning as borrowers in their respective business sectors, to the universe of member state best practices, such as Britain’s Business Bank or France’s

Fichier Bancaire des Entreprises.

The Spanish approach to getting more bank finance flowing to SMEs

The information asymmetry issue

Deficient, insufficient or unreliable information about finance-seekers translates, in general terms, into less abundant or more costly bank credit for SMEs.

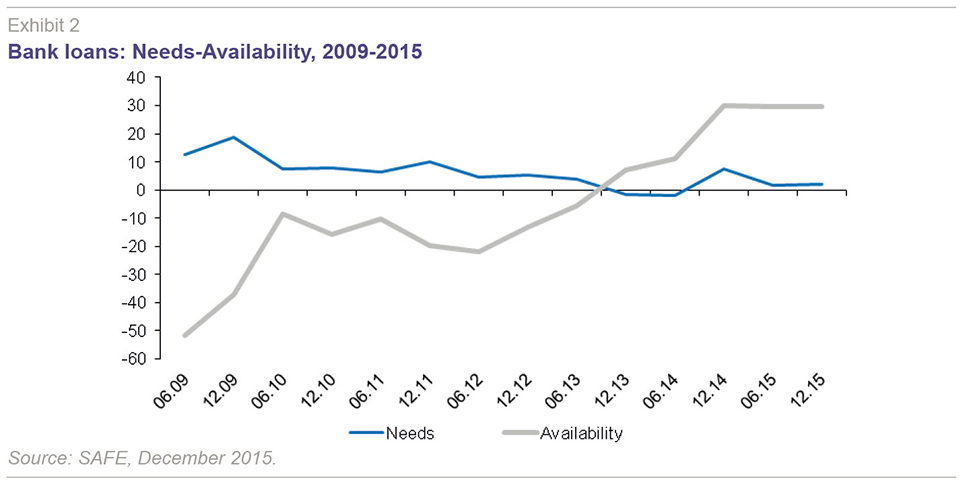

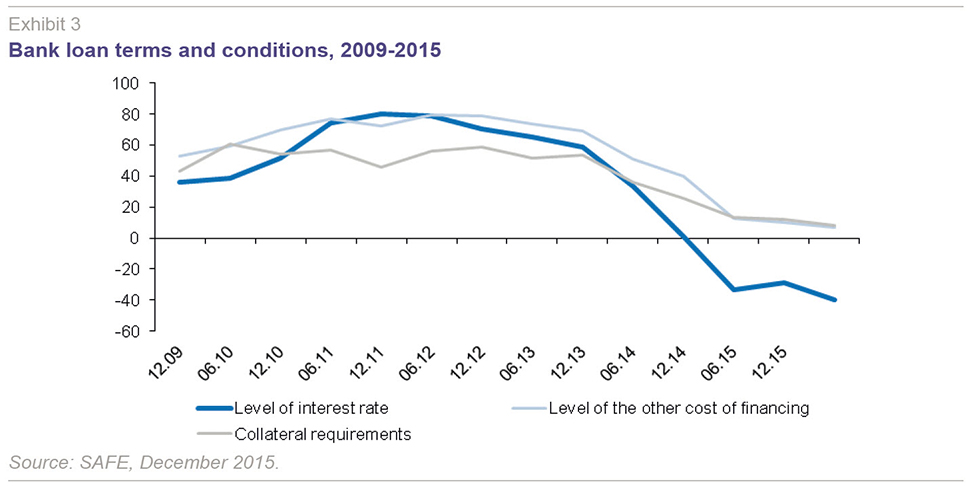

Using the SAFE data once again for 2009-2015, and in line with the developments outlined in the first section, it might appear that this is not an issue in Spain: as illustrated by Exhibits 2 and 3, there has been a significant improvement in the availability of bank loans, coupled with a sustained improvement in the terms and conditions attached to such loans.

Nevertheless, the reasons justifying this trend (economic recovery, improved health of the banks, etc.) are independent of the information gap the legislation attempts to close, so that it remains valid as an objective.

This information asymmetry becomes evident in the credit assessment process, in which the lack of information faced by the banks gives rise to what Akerlof (1970) termed the “adverse selection” effect, which ultimately leads to application of the same terms and conditions to projects with different risk profiles. It also comes into play during the loan granting process, in which the bank assumes a moral hazard given the possibility that the borrower will use the funds for purposes other than those contemplated. Faced with either scenario, a bank may conclude that the loan applicant is not sufficiently solvent, thus choking off the flow of funding or shutting it off altogether, or decide to levy a surcharge on the universe of SME borrowers as a whole. In either event, creditworthy borrowers may end up out of the market or involuntarily subsidising their less creditworthy peers.

One of the ways in which the banks have traditionally overcome this lack of sufficient information when it comes to granting a loan, and even at later stages of the lending process, is to use signals transmitting information about the intrinsic worth of the project and the borrower’s commitment thereto.

Such reliable signals notably include the willingness on the part of the borrower to provide, in exchange for additional funding or a lower interest rate, collateral which gets transferred to the lender if the venture’s earnings are not sufficient to repay the loan in full or personal guarantees which give the guarantor a vested interest in the project, thereby signalling his or her confidence therein. Borrowers can also demonstrate their confidence in the quality of their projects by injecting more capital or accepting contractual terms designed to enhance protection of the lender’s rights. The lender, meanwhile, can make use of other external information sources, such as those provided by the Bank of Spain’s Central Credit Register to reporting entities and reporting institutions, insofar as they help curb the adverse selection phenomenon.

In addition to these external signals, the banks gather other signals during the course of their long-standing relationships with their customers which provide them with qualitative information about these entities and their debt servicing capabilities.

Regulatory measures taken in Spain to get more bank finance flowing to SMEs

With the aim of mitigating the information asymmetry issue, Title I of Spanish Law 5/2015 (Improving access to bank finance for SMEs) stipulates two mutually-independent obligations:

- Provision of prior notice: Whenever finance providers [7] decide to cancel or reduce by at least 35% the flow of financing they had been extending a given SME, they must so notify the SME, [8] using any method that enables confirmation of receipt, with a lead time of at least three months, such that the affected borrower has enough time to find new sources of finance or recalibrate its liquidity management strategies.

The notice is not binding and does not therefore oblige the bank to subsequently cancel or reduce the loan, nor does it amend the binding content of the loan agreement or affect its effectiveness between the parties.

Law 5/2015 introduces a definition of ‘flow of financing’ which, in broad terms, encompasses all agreements whose overriding purpose is to finance the working capital and general business activity of the SME, the terms of which, as a general rule, in the ordinary course of business, do not exceed one year.

- Delivery of the ‘SME-Financial Information’ document: Within 10 days of provision of the above notice, the finance providers are obliged to furnish the borrower with an extensive report on its financial situation and payment history in the form of the so-called SME-Financial Information document, which must also include a borrower risk rating. The idea is to reduce the information gap faced by potential new financiers when analysing the loan-seekers’ creditworthiness, thus facilitating the search for alternative sources of financing.

Additionally, in order to enable all borrowers in receipt of flow of financing to make the best possible use of their financial information, making strategy adjustments as warranted, the finance providers are similarly obliged to furnish the SME-Financial Information document within 15 days if so requested by the SME. This measure has the potential to reinforce new lender or investor confidence. However, to make sure its cost is not borne by the original lender, it is subject to payment by the SME of the fee set by the original provider.

Law 5/2015 envisages a series of situations in which neither obligation is applicable, such as the provision of very short-term paper, when the decision to terminate or downsize the loan has been mutually agreed, when the borrower is legally insolvent or has breached its obligations or when financial conditions have deteriorated without warning without leaving time for the required notice period.

The failure to provide the stipulated notice and/or deliver the credit document does not mean that the provider cannot subsequently cancel the loan but does constitute a breach of compliance and disciplinary regulations which could give rise to a fine for the breaching entity.

The law itself goes one step further: with a view to ensuring that the above-listed requirements emerge as an effective tool and the information generated is comparable and reliable, it tasked the Bank of Spain with specifying the content and format of the SME-Financial Information report, establishing the corresponding template and drawing up methodology for standardising the SME credit scoring process.

Bank of Spain Circular 6/2016 [9]

Before embarking on an analysis of the Circular, it is worth highlighting one of the goals pervading its elaboration, namely that of making sure it did not imply disproportionate costs for the bound institutions; accordingly, in addition to the public consultation process which customarily accompanies the drafting of regulations of this order, feedback has been sought from the finance providers throughout the process, mainly channelled through the sector associations.

The SME-Financial Information report

The overriding purpose of the SME-Financial Information report is to reduce, by leveraging the information in the hands of the original lending institutions, the information asymmetry faced by potential SME lenders, thereby minimising the fallout from adverse selection and moral hazard phenomena intrinsic to a shortfall of information for credit assessment purposes.

The contents of the document have been designed following the legislator’s instructions with a dual objective. Firstly, to compile the minimum amount of information about an SME deemed necessary for a risk analyst to appropriately assess the risk implied by granting that SME a new loan. In reducing the information gap vis-a-vis the new financier and, as warranted, the costs of so doing, two goals are pursued: (i) accelerating the loan analysis and granting process; and, (ii) better aligning funding costs with individual SME risk profiles.

Secondly, so that the SME-Financial Information report is truly useful, an attempt was made to ensure that the information contained in the document is reliable and comparable, so that the new providers can both rely on its contents and automate their risk assessments on the basis of the data contained in the report to the extent possible. To this end, the contents of the document were designed by relying to a large degree on the data compiled in the statements filed monthly by financial providers with the Bank of Spain’s Central Credit Register (CIR for its acronym in Spanish) so as to guarantee data availability, quality and comparability.

Elsewhere, it is worth noting that the reference date for the document is the last day of the month prior to the date of notice or the date of the report request, although the document must be filled out using the most updated information the entity deems relevant.

The SME-Financial Information document is divided into five sections:

- SME information statements submitted by the reporting institution to the CIR during the last five years. Given that a portion of the data reported by the financial institutions to the CIR is intended for the Bank of Spain in its role as supervisor and is by extension strictly confidential, the fields that have to be filled in for the purposes of the SME-Financial Information report have been limited to those included in the feedback provided by the Bank of Spain to the reporting institutions. In short, the entities must include in the SME Financial Information report the data fields that they have reported on the SME.

To this end, they must provide the last four monthly statements and those corresponding to the end of each quarter for the five years prior

to the date of notice or report request.

- Data reported to firms that provide financial solvency and credit analysis services. Here the finance providers must include the data that remain on record at these firms as of the document reference date.

- Credit history. The document must include information about the transactions between the borrower and the reporting institution, including those still outstanding and those cancelled during the last five years. Specifically, the following information:

- A list of historical and outstanding loans, specifying the essential particulars of all transactions arranged between the SME and the finance provider, i.e., basic transaction data (type of product, use of proceeds, amount granted, date of grant, etc.), the current status of the exposure (limit granted, balance drawn down, status of any refinancing or restructuring work, etc.), and the collateral and personal guarantees (type of guarantee, coverage, etc.) associated with each transaction.

- A chronological list, indicating the current status, of any unserviced obligations, specifying, among other things, the dates of non-performance and the amounts unserviced. In the absence of any non-performance, the reporting entity must provide an explicit statement attesting to the fact that the borrower has met its obligations in full.

- A list of any bankruptcy proceedings, refinancing agreements or out-of-court payments, embargoes, enforcement proceedings or other legal incidents: The reporting entity must inform of any such situation affecting the SME in the last five years to which it has been party.

- A list of insurance contracts related with the flows of financing: Entities shall include information about any insurance policies which serve to mitigate the credit risk.

- Statement of fund flows for the last year in respect of the contracts comprising the flow of financing. This is the only section of the document for which the entities are not obliged to use a specific template so that each has the freedom to report this information using the format that best matches its IT systems.

- Risk rating. One of the most significant novelties introduced by the Spanish regulation is the requirement that the finance providers score their SME customers’ ability to service their financial commitments. With the aim of making the ratings comparable across the sector, thereby facilitating the search for new sources of financing, the banks must use the methodology outlined in the next section.

In addition, leveraging the data bank built up and the highly-advanced and tried-and-tested tools designed by the Bank of Spain’s Central Balance Sheet Data Office, the document must also include, in order to complement the risk rating, information about the borrower’s relative positioning in its respective business sector. This relative positioning is articulated around analysis of certain financial ratios which rank the SME by quartile relative to the companies comprising its specific business sector and is as such a proxy for an analysis of the SME’s strengths and weaknesses relative to its competitors.

Risk rating methodology

One of the most important aspects of the Circular is how it fleshes out this methodology. The methodology is designed to ensure standardised and comparable SME risk ratings. It is not intended to substitute the institutions’ internal rating models or risk management criteria, which vary greatly in terms of complexity and utilisation from one entity to the next.

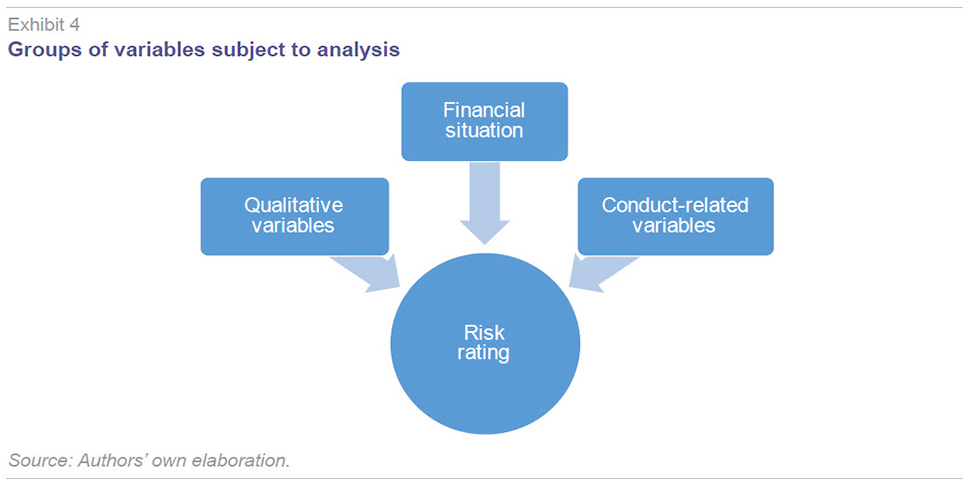

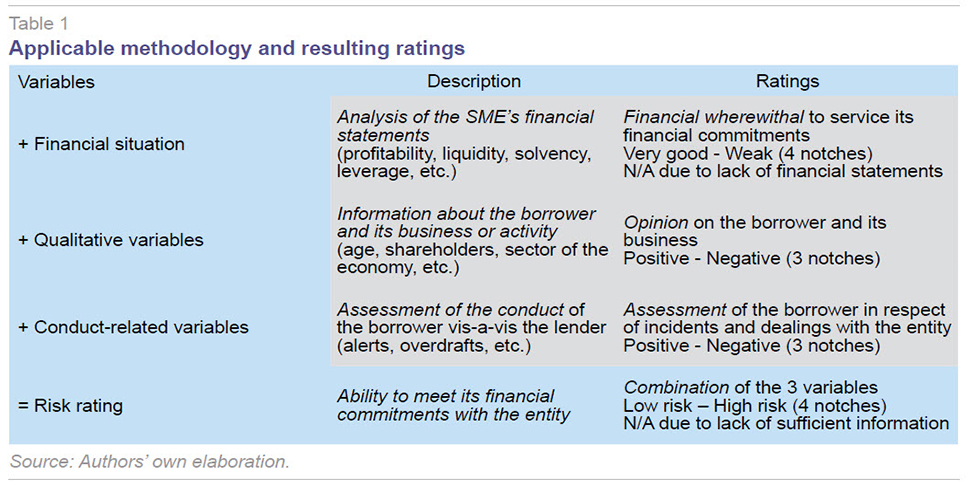

The purpose of the methodology is to have the entities assess their borrowers’ ability to service their financial commitments, expressed as one of the following risk ratings: low risk, medium-low risk, medium-high risk, high risk or ‘not available’ (for instances in which there is not enough information to apply the methodology). To this end, the methodology draws from the universe of information available to the financial institutions which covers not only that related with the borrowers’ financial situation but also that acquired by the entity in the course of its relationship –personal and contractual– with the SME. The methodology is underpinned by three pillars: (i) analysis of the SME’s financial statements; (ii) the lender’s knowledge of the customer, its business, activity or group; and (iii) the SME’s conduct over time in its contractual dealings with the institution. The sharing of information about the latter two aspects, in a manner that is comparable across the sector, is what adds the most value to the risk rating process, by making a significant contribution to reducing the effects of the information asymmetry that faces potential new financiers.

The immediate consequence of the foregoing is that two financial institutions will not necessarily award a given SME the same rating as their knowledge of and experience with the firm in question may well vary from one firm to the next. For this reason, the Circular does not prescribe a specific risk weighting to each group of variables but rather gives the finance providers the responsibility of establishing the relationship between the scores given to each category and the final rating assigned to the borrower. However, it is mandatory to rank each of the groups of variables in order of priority from 1 to 3.

By means of this flexibility the methodology seeks to guarantee high-quality ratings. To ensure correct use of this flexibility the institutions are required to provide justification, for each borrower, of the scores awarded for each group of variables analysed and the order of importance given to each group within the overall risk rating.

- Financial situation of the borrower. This assessment must make use of the ratios stipulated in the Circular, selected from those included in the sectoral rates of non-financial corporations’ reports used by the Bank of Spain’s Central Balance Sheet Data Office, using the borrower’s most up-to-date financial statements. The overall assessment of these ratios results in ratings of the borrower’s financial situation ranging from very good to weak, ‘not available’ being an option if there are no financial statements or no sufficiently recent statements.

In the event it is not possible to use some or all of the ratios, the institutions must evaluate at least each borrower’s business performance, profitability, liquidity, leverage and solvency.

- Qualitative variables: The institutions must evaluate (issuing a positive, neutral or negative opinion) their knowledge of the borrower as a customer, of their business and, if applicable, of the support they receive from their shareholders or the corporate group to which they belong. To this end, they must use the qualitative information available within their management systems and, at least, provide the information related to the length of time the borrower has been in existence and has had business dealings with the lender and that related to the sector of the economy in which they operate.

- Conduct-related variables: The institutions must assess borrowers on the basis of their conduct vis-a-vis the entity and the alert systems put in place by the latter. The resulting rating can be positive, neutral or negative.

The combination of the three groups of variables will yield an assessment of the borrower’s credit profile, subject to the following set rules:

- If the assessment of the borrower’s financial situation is ‘not available’, then the overall risk rating may also be ‘not available.’

- If the assessment of the conduct-related variables is ‘negative’, then the borrower’s overall risk rating must be ‘medium-high risk’ or ‘high risk.’

Along with the final risk rating, the institutions must disclose in their

‘SME-Financial Information’ reports the ratings awarded for each group of variables, additionally ascribing an order of importance to each, 1 being the most important and 3 being the least important, without scope for repetition and applied consistently over time for similar groups of borrowers.

The borrower’s relative positioning in its respective business sector

For the most recent financial year for which there is accounting information, the entity must provide the borrower, along with its risk rating, information about its relative positioning in the sector in which it operates.

To this end, the entities will have access to a specific application used by the Bank of Spain’s Central Balance Sheet Data Office that will generate this information by inputting the customer’s identification particulars and financial statement details. Use of this tool will generate, by means of the same ratios as are used to analyse the borrower’s financial situation, the quartile in which the borrower ranks relative to the rest of the players in its respective business sector. This yields a visual snapshot of the borrower’s performance relative to its peers. In addition, in order to encourage use of this tool by the borrowers themselves, the institutions must inform the latter of the possibility of obtaining, free of charge, a more detailed individual study containing sector benchmarking data from the Bank of Spain’s Central Balance Sheet Data Office with which to perform more exhaustive analysis of their business performance.

Lastly, we would like to note that in this paper we have sought to expound the context, spirit and objectives surrounding the drafting of the regulation aimed at improving access to bank finance for SMEs. We must await its implementation in practice, from October 11th, 2016, the date of effectiveness of Law 5/2015 and Bank of Spain Circular 6/2016, to be able to assess the degree of delivery of the stated objectives. Regardless, these regulatory developments undeniably mark a milestone in terms of the transparency of the financial institutions’ decision-making. The hope is, on the other hand, that the SMEs will play an active role in this new paradigm, demanding but also providing more and better information.

Notes

The EC’s pro-SME policy stance is clear; what is not so clear is the effectiveness of these policies, according to sceptics. Some of these sceptics defend the role of large firms relative to SMEs because they can exploit economies of scale and more easily undertake the large fixed costs associated with research and development (R&D), thus making them better at innovating and boosting productivity; they also hold that large firms can offer more and higher-quality jobs, so having a bigger impact on the poverty alleviation effort. Others believe that policy makers should not focus on propping up a particular company size but rather focus on improving the full range of institutions that affect the overall business environment.

Data published by the Spanish government’s Department of Industry and Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises (hereinafter, DGIPYME for its acronym in Spanish).

Retrato de la Pyme [Portrait of the SME] - DIRCE (Spain’s Central Companies Directory) as of January 1st, 2015. The DGIPYME.

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0468&from=EN This plan, starting from the fact that

“a lot of SMEs don’t get all the financing they ask from banks in Europe (in the euro area, 35% of SMEs didn’t get the complete financing they asked their banks for in 2013),” seeks to “move the EU closer towards a situation where, for example, SMEs can raise financing as easily as large companies; costs of investing and access to investment products converge across the EU; obtaining finance through capital markets is increasingly straightforward; and seeking funding in another Member State is not impeded by unnecessary legal or supervisory barriers.”

The references made in this paper to finance providers shall be understood to encompass both credit institutions and specialised lending institutions, by virtue of application of article 7 of Law 5/2015.

The references made in this paper to SMEs shall be understood to include self-employed professionals, having been included within the scope of Law 5/2015.

Bank of Spain Circular 6/2016 (of June 30th, 2016), addressed to banks and specialised credit institutions, specifying the contents and format of the document titled SME-Financial Information and the risk classification methodology contemplated in Spanish Law 5/2015 (of April 27th, 2015) on the promotion of business financing.

References

AKERLOF, G. A. (1970), “The Market for “Lemons,” Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 84, No. 3: 488-500.

Isabel Payo Alcázar and Pedro Pérez Cimarra. Bank of Spain