An assessment of fiscal slippage

at the regional government level in Spain

A closer look at the diversity of fiscal performance at the regional level provides insights into the possible causes behind recent slippage. However, even in the face of an improved regional fiscal outlook for 2016, it will be necessary to incorporate these insights into new fiscal strategies to ensure budgetary stability over time.

Abstract: The public deficit has been a key issue for economic policy in Spain since the start of the crisis. In general terms, the fiscal performance of local corporations has served to offset the deterioration of Spanish public finances at other levels of government, recording surpluses and reducing borrowing in nominal terms. But, the rapid increase of regional financial liabilities has become a source of concern. However, judging by the projections available for 2016, it seems that the regional government deficit is expected to return to pre-crisis levels and risk will shift to the central government, including the Social Security funds. Understanding and correcting the causes of regional fiscal slippage is a pre-requisite for designing on-target fiscal strategies to address this problem in the longer-term.

[1]

The public deficit has been a core concern of Spanish economic policy since the start of the crisis. An ample surplus in 2007 rapidly transformed into a deficit in the order of 10% of GDP. In tandem, the public debt ratio soared from below 40% of GDP to exceed the 100% threshold.

There are multiple causes of this fiscal deterioration, including: counter-cyclical fiscal policy measures and the increased cost of spending programmes, such as unemployment benefits; the collapse in tax revenue- far more pronounced than was expected in light of the estimated elasticity of tax receipts to GDP, which ultimately revealed a worrying structural shortcoming in the Spanish tax system; a growing debt service burden; the need to financing the restructuring of the financial system; and the decline in nominal GDP, pushing up any ratios using this as their denominator. The estimates compiled by Delgado, Gordo and Martí (2015) divide the drivers of the increase in debt into four factors. The most relevant in quantitative terms (accounting for over half of the cumulative increase) is the deterioration in the primary deficit, a factor which encompasses the counter-cyclical measures, the impact of the automatic stabilisers, and the intrinsic weaknesses of the fiscal system. The debt burden ranks second. Next, the measures that have led to more debt but do not compute for excessive deficit procedure purposes (such as the bank restructuring exercise). Lastly, the drop in nominal GDP.

When the above factors are observed at the various levels of government in Spain, the reality is highly diverse. The local corporations have served to offset the deterioration as a whole, recording surpluses and reducing their borrowings in nominal terms. The Social Security administration is running substantial deficits that have not waned with the recovery in job creation (Lago Peñas, 2016) but have been financed by a reserve fund that has prevented the generation of new debt. The central government is accountable for the largest spike in deficit and debt alike, albeit largely due to its key role as stabilising agent and lender of last resort to other public agents and the financial system. Lastly, the regional governments have seen their financial liabilities jump from roughly 5% of GDP in 2007 to close to 25% today due to very considerable deficits that have, on average, come to surpass 3% of GDP, emerging as a cause of concern in Spain and abroad. The purpose of this paper is to examine this trend at the regional level, particularly the mismatch between the figures reported relative to the regional governments’ deficit targets. Only by properly understanding the causes of this fiscal breach will the Spanish public sector be able to design on-target fiscal strategies directed at the heart of the problem.

The dynamics of regional deficit target non-compliance

We define deficit compliance as the difference between the observed deficit (-) or surplus (+) and the stated deficit/surplus target, both expressed as a percentage of regional GDP. Positive readings mean that the deficit has come in narrower than targeted and vice versa.

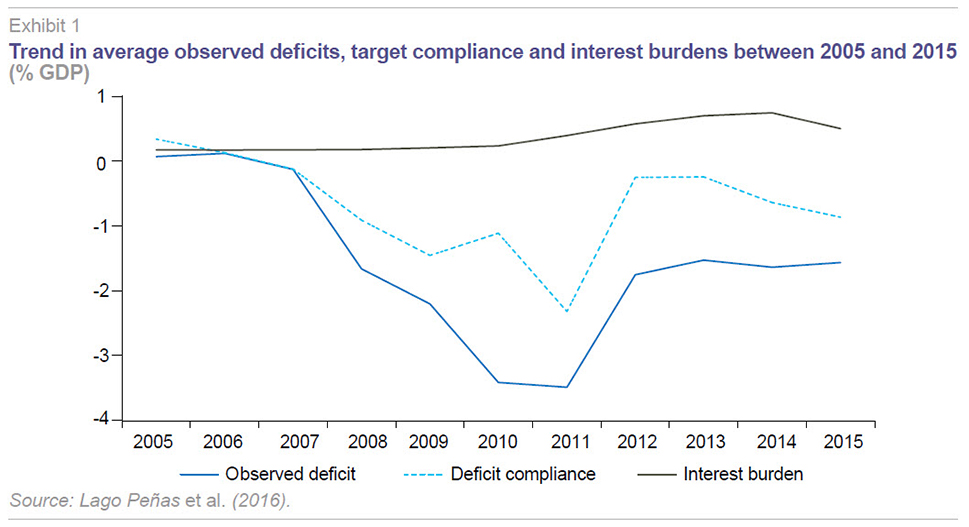

Exhibit 1 illustrates the trend in the average of three variables between 2005 and 2015: the observed deficit, deficit compliance and the interest burden, each of which are expressed as a percentage of GDP in each region. Starting from a situation close to that of a balanced budget in the run-up to the crisis (2005-2006), matters began to deteriorate in 2007, with the worst reading recorded in 2011, when the regional deficit averaged 3.5%. The improvement between 2011 and 2012 was very noteworthy, putting the deficit once again within 2%. Since then (until 2015), the deficit has stabilised at slightly over 1.5%.

The deficit compliance dynamics are similar, albeit with nuances. Until 2010, the deficit targets were adjusted progressively to the deficits reported, such that the non-compliance trend is not as adverse as the trend in the deficit per se. From 2011, this adjustment process became less pronounced and since 2013 the target-setting process has been independent of the trend in the underlying numbers. The roadmap set for the deficit (gradual but inflexible) means that a reported deficit in line with that of prior years has the effect of exacerbating the degree of non-compliance.

Lastly, the trend in the interest burden reveals stability until 2010 and progressive growth between then and 2014, when it approached 1% of GDP.However, the drop in interest rates and the country risk premium in Spain, coupled with the financial support programmes approved by the central government, had the effect of significantly reducing the (interest) burden in 2015, bringing it in line with the average level of 0.5% of GDP.

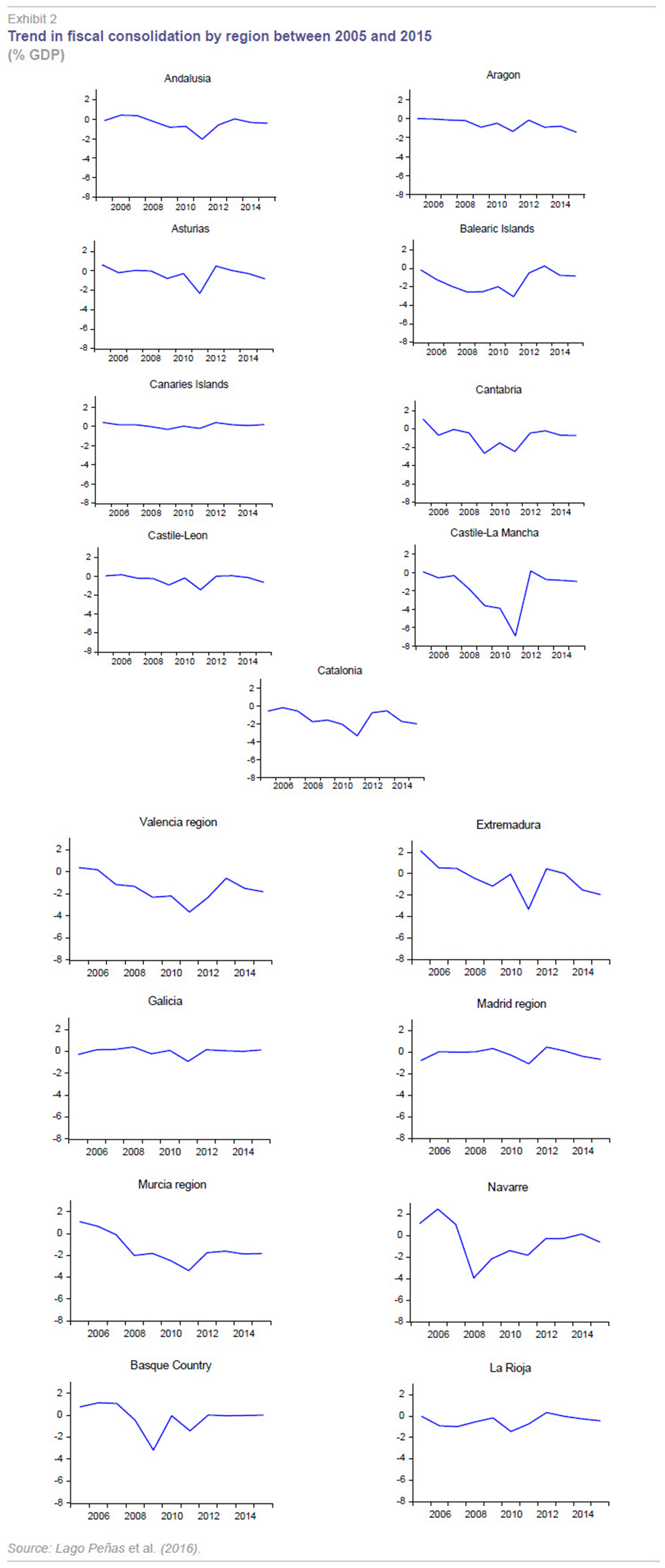

The above analysis masks the existence of highly divergent regional dynamics in terms of the pattern and absolute level of deficit target non-compliance. Against this backdrop, Exhibit 2 depicts the trend in the

deficit compliance variable individually for each of Spain’s 17 regions between 2005 and 2015. The exhibit shows the aforementioned diversity. There are regions that have missed their targets by only a narrow margin and even some in which compliance has predominated, compared to others where target breaches have been the norm.

It is possible to group the regions into categories and flag idiosyncratic behaviour.

[2] The first category comprises eight regions (Andalusia, Castile-Leon, Asturias, Aragon, Canary Islands, Galicia, Madrid and La Rioja).These are the most compliant and consistent regions as regards adherence to targets over time. Within this category, it makes sense to distinguish a subgroup comprised of the Canary Islands, Galicia and Madrid, in which target compliance has been the norm and whose performance is consistently very close to 0, occasionally even recording a surplus.

The second category is made up of the four regions along the Mediterranean: Murcia, Valencia, Catalonia and the Balearic Islands. The defining trait in this instance is systematic target breaches, with matters gradually deteriorating between 2005 and 2011, when non-compliance was in the order of -4%, followed by substantial improvement in 2012 and 2013 (with the Balearic Islands registering a positive reading in 2013), since which time their performance has worsened once again.

The third cluster includes the Basque Country and Cantabria, which rank somewhere in between the first two categories. Although they are not capable of staying as close to targets as the constituents of the first category, their deviations are more one-off and less pronounced than those of the second group; moreover, they have been improving significantly on the budget stability front since 2011.

Navarre and Castile-La Mancha are the two regions with the most asymmetric dynamics and are outliers with respect to the rest of their peers. Navarre went from strongly positive readings until 2007 (peaking at over +2%) to suffering the biggest collapse in 2008, due to the unique nature of the so-called “foral” financing system: the drop in tax revenue is felt more keenly in this region than elsewhere in Spain because of the lack of withholdings and payments on account. In comparison with the other foral region (the Basque Country), Navarre is having a harder time balancing its budget once again. In the case of Castile-La Mancha, the deterioration observed between 2007 and 2011 is unparalleled. Nor, however, has any other region improved its situation by as much or as quickly, having started to meet its targets as early as 2012. Lastly, Extremadura’s performance resembles that of Cantabria and the Basque country somewhat, differing most notably in the deterioration observed between 2013 and 2015, compared to improved budget stability in the case of its northern counterparts.

The causes of non-compliance between 2005 and 2015

Econometric analysis of the drivers of non-compliance at the regional government level as a whole between 2005 and 2015 yields the following results (Lago Peñas et al., 2016):

- The level of compliance in a given year has depended directly on what had happened the prior year. The reason is that the starting point is more challenging the bigger the target breach the prior year.

- The level of compliance appears to be inversely correlated to the deficit cuts approved for the year in question. Deficit targets have been missed by a wider margin the more ambitious the targets.

- The regional governments with the highest per capita revenue have tended to fare better with respect to their targets.

- Political changes have helped in the achievement of fiscal objectives in the year after the change in office for two reasons. Firstly, at the beginning of a new term in office and with new officials in charge it is easier to take unpopular decisions. Secondly, because the fact of holding elections and electing a new government usually brings previously concealed sources of deficit to light (unprocessed invoices, inflated revenues). ‘Cleaning up’ the accounts raises the deficit in year n (when the change of incumbent is done) and reduces it in year n+1.

- Coincidence between the party in government at the regional and national levels appears to foster target compliance to the extent that ultimate responsibility for fiscal austerity lies with the latter and the former tends to be more cooperative with what is seen as a ‘friendly government’. However, this result is less sensitive to changes in the econometric methodology and sample.

In contrast, the exercise reveals scant significance, as a general rule, with respect to other factors often rolled out in the course of the public debate. Specifically:

- The proximity of elections has not clearly or systematically increased target non-compliance, the theory being that political considerations can lead to delaying spending cuts or tax hikes, encouraging the opposite behaviour.

- The estimates do not back up the thesis that the debt burden has played a meaningful role as a general rule.

- Although one might think that the regions that have seen their primary spending increase the most in the recent past would have the greatest scope for cutting back in the present day, thereby meeting the targets set, the econometric estimates demonstrate otherwise. [3]

That being said, the econometric findings show that the above list is not all-encompassing in terms of possible explanatory variables.

[4] The interpretation is two-fold. Firstly, the figures suggest that there have been regional governments that have taken fiscal austerity more seriously than others, assuming a higher political cost and taking advantage of their autonomy, particularly on the spending side of the equation, to meet their targets by making bigger cuts.

Secondly, some non-compliance is attributable to unforeseen developments of all manner, such as court sentences or decisions taken at other levels of government that impact the regional governments’ expenditure or income. Both lines of reasoning warrant an examination of case studies to achieve a better understanding of the diversity of results.

Target compliance prospects for 2016

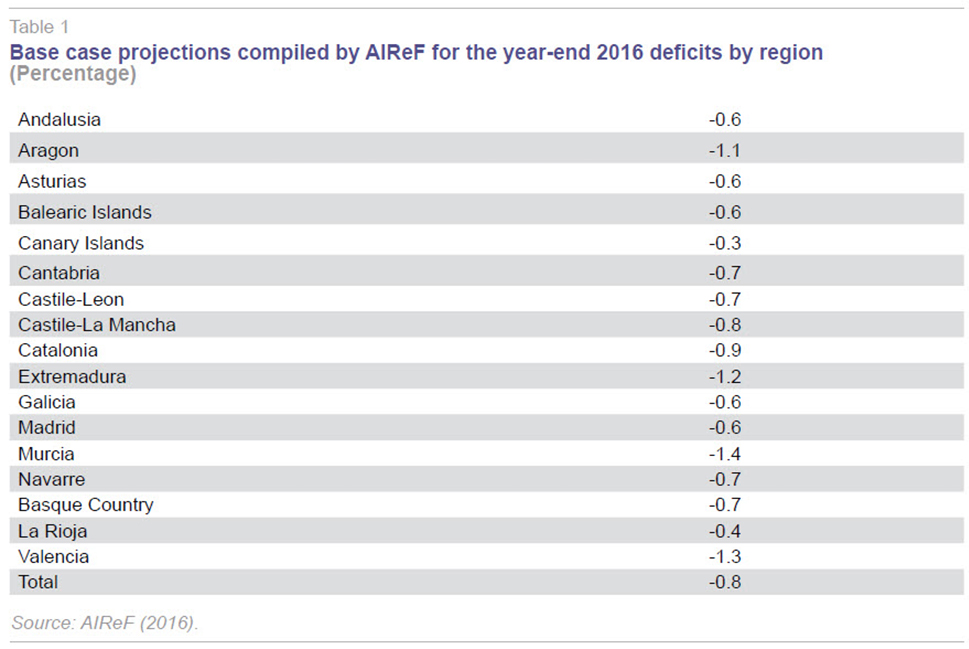

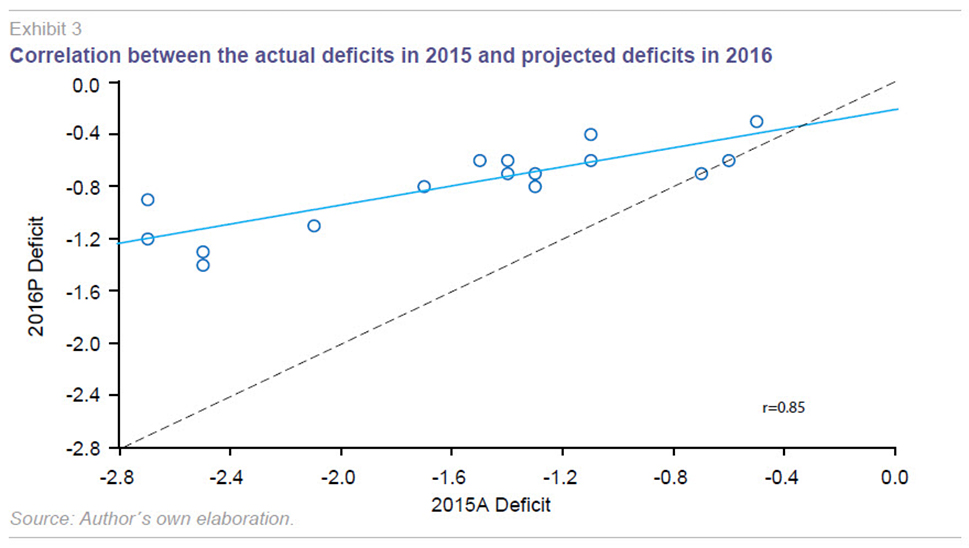

At this juncture of the year, projections are available for deficit target compliance by region for 2016. They have been compiled by AIReF (2016) (Spain’s so-called independent fiscal responsibility authority) using the first-half budget outturn figures. Table 1 replicates the corresponding figures. Exhibit 3, meanwhile, shows the relationship between the year-end 2015 figures and the projections for 2016. A combined reading of the table and exhibit points to a very considerable improvement. For the first time since the start of the crisis, the deficit is expected to go below the 1% threshold. Moreover, the regional governments are expected to almost comply with their deficit target for 2016, following the revision from 0.3% to 0.7% announced a few months ago, which was tantamount to freezing the target missed in 2015. Secondly, deficits are expected to be reined in far more significantly in the regions in which the imbalance was more pronounced in 2015. This outcome is illustrated graphically by the slope of the regression line in the exhibit. If the reduction were similar across the regions, the line would be parallel to the line bisecting the square. The slope would be the same; what would differ would be the intercept. In contrast, the regions that already met their targets in 2015 and therefore worked with more room for manoeuvre in 2016 have used the leeway to increase their spending. Only the Canary Islands looks likely to comply with the original deficit target for 2016 (0.3%).

Looking closer at the variables accountable for this very encouraging deficit performance, the AIReF attributes responsibility in full to just two factors: the improvement in the financing panorama and one-off budget items not recurring in 2016. For the regional governments as a whole, the deficit is projected to decline by 90 basis points. The AIReF attributes approximately two-thirds of this improvement to the financing phenomenon and one-third to the non-recurrence of one-off charges. Deficit-cutting measures are insignificant on aggregate. In all, the AIReF (2016) sees compliance by the regional governments of their targeted deficit of 0.7% in 2016 as “feasible but tight;” that being said, compliance is considered improbable in the case of Castile-La Mancha and Catalonia and highly improbable in Aragon, Extremadura, Valencia and Murcia.

The projections compiled by Díaz and Marín (2016) for FEDEA are similar on aggregate. In their opinion, the regional governments as a whole have overstated their revenue budgets for 2016 (albeit by less than in 2015), such that they will end the year with a deficit of 0.9 points of GDP. The 0.2 point shortfall with respect to target would be salvageable with rigorous spending control during the second half of the year.

Conclusions

The regional governments have been a recurring source of concern in terms of evaluating compliance of the fiscal consolidation targets. However, judging by the projections available for 2016, the target for this year having been relaxed, the problem seems to be mostly resolved. The regional government deficit is expected to return to pre-crisis levels with risk shifting to the central government, including the Social Security funds. If we take this at face value, however, we run the risk of ignoring the need to tackle reforms and define more ambitious consolidation strategies at the regional level. There are two key reasons for avoiding this risk.

Firstly, the improvement in the deficit has to do primarily with the growth in revenues provided by the financing model in place in most of the regions (the so-called common regime). A model based on the use of withholdings and payments on account that are settled with a significant lag which can, as shown in 2008 and 2009 (Lago Peñas and Fernández Leiceaga, 2013), generate a false sense of financial sufficiency. As warned by the AIReF itself, the tax collection numbers for 2016 are tracking below estimates and this implies a risk of a reduction in the sums ultimately allocated to the regional governments.

Secondly, the divergence among the various regions remains very pronounced. As we have seen throughout this paper, certain regions have met and continue to meet their targets. Others have not. Although the regional governments on aggregate have improved their situation, certain regions continue to face enormous difficulty in reining in their deficits.

This yields three conclusions. The first is that reforming the regional financing regime remains necessary and pressing in order to reinforce the regional governments’ financial autonomy and sufficiency, but also to tighten their budget restrictions. There is major risk the anticipated improvement in the system’s revenue alone will not resolve the underlying issues.

The second is that the workings of the system of payments on account and withholdings need to be reviewed. The regional governments need real-time information about the trend in their revenue; and they need to feel it in their cash receipts so that they take the required offsetting measures when trying to stick to budget. Against this backdrop, the proposal made by Hernández de Cos and Pérez (2015) for the introduction of an adaptive mechanism by which the revenue estimate gets updated over the course of the year with an impact on payments on account could be a good solution. Cuenca (2015), meanwhile, suggests bringing the calculation of the definitive settlement forward by one year and having the central tax authority directly allocate monthly tax collection revenues to the regional governments. There are accordingly technical solutions worth exploring. What is needed is reform zeal.

Lastly, awareness is required that fiscal performance is not homogeneous across the various regional governments. There are very compliant regions, while others systematically breach. Moreover, the motives underpinning these results are very different. In some instances, a financing shortfall is evident. In others, fiscal irresponsibility is more to blame. What we need to do is learn from the success stories and define individualised fiscal consolidation roadmaps and strategies. And when it comes to monitoring and encouraging target compliance, it would be a good idea to introduce a greater degree of automation in terms of the protocols triggered by non-performance and improve the administrative processes for closing the loopholes which lead to weak adherence to the fiscal austerity plans presented by the regional governments.

Notes

This article is based on research sponsored by Funcas, the full results of which are available for review at Lago Peñas et al. (2016).

Lago-Peñas et al. (2016) perform cluster analysis that supports this categorisation.

Our findings coincide with those of Leal and López Laborda (2015) with respect to the dynamic nature of the process (complying today is crucial to being in a position to do so once again tomorrow), the irrelevance of the financial burden and the importance of the non-financial resources on hand.

The coefficient of determination was around 70%.

References

AIReF (2016), Report on anticipated compliance of the budget stability and public debt targets and spending rules at the various levels of government in 2016 dated July 19, 2016 and available at the following link

http://www.airef.es/system/assets/archives/000/001/597/original/

2016_07_22_Informe_de_Cumplimiento_Esperado_con_actualizaciones.pdf?1469184047CUENCA, A. (2015), “Las entregas a cuenta en el sistema de financiación de las CC.AA. de régimen común: problemas y opciones de mejora,” [Payments on account in the ‘common’ regional government financing regime],

Fedea Policy Papers, 2015/10.

DELGADO, M.; GORDO, L., and F. MARTÍ (2015), “La evolución de la deuda pública en España en 2014” [The trend in public debt in Spain in 2014],

Economic Bulletin of the Bank of Spain, July-August: 41-56.

DÍAZ, M., and C. MARÍN (2016), “Análisis de los presupuestos de las CC.AA.: Cumplimiento 2015 y valoración 2016,” [Analysis of the regional government budgets: 2015 performance and 2016 assessment],

Estudios sobre la Economía Española, 2016/08, Fedea.

HERNÁNDEZ DE COS, P., and J. PÉREZ (2015), “Reglas fiscales, disciplina presupuestaria y corresponsabilidad fiscal” [Fiscal rules, budget discipline and shared budget responsibility],

Papeles de Economía Española, 143: 174-184.

LAGO PEÑAS, S. (2016), “Fiscal Consolidation in Spain: State of Play and Outlook,”

Spanish Economics and Financial Outlook (SEFO) 5(1): 41-48.

LAGO PEÑAS, S., and X. FERNÁNDEZ LEICEAGA (2013), “Las finanzas autonómicas: expansión y crisis, 2002-2012” [Regional finances: expansion and crisis, 2002-2012],

Papeles de Economía Española, 138:129-146.

LAGO PEÑAS, S.; VAQUERO, A., and X. FERNÁNDEZ LEICEAGA (2016), “¿Por qué incumplen fiscalmente las Comunidades Autónomas?” [Why are the regional governments missing their deficit targets?], Funcas.

Working Papers, 784.

LEAL, A., and J. LÓPEZ LABORDA (2015), “Un estudio de los factores determinantes de las desviaciones presupuestarias en las Comunidades Autónomas en el período 2003-2012” [A study of the factors driving deficit target shortfalls at the regional level between 2003 and 2012”],

Investigaciones Regionales/Journal of Regional Research, 31: 35-58.

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics and Director of the Governance and Economics research Network (GEN), Vigo University.