Policy interest rates: The ECB’s strategic pause and medium-term outlook

With inflation near target and growth subdued, the ECB has paused after eight rate cuts. The balance between disinflation, wage pressure, and fiscal risk will determine whether stability or tightening comes next.

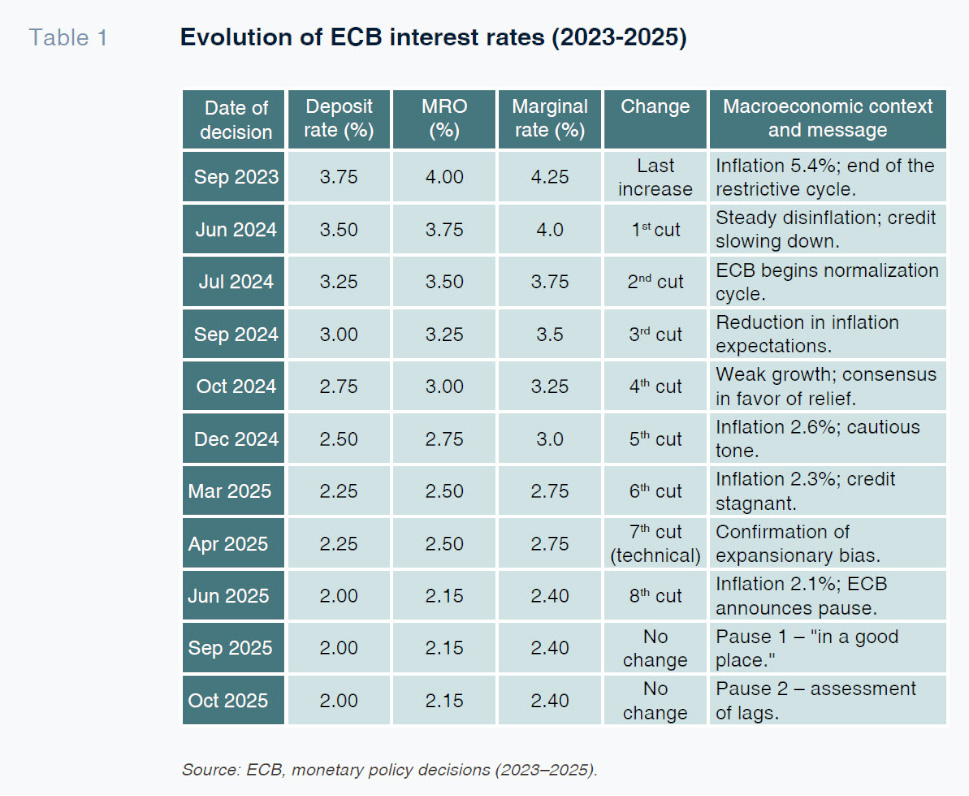

Abstract: After the most intense tightening in its recent history, the European Central Bank (ECB) reduced its deposit rate eight times between 2024 and 2025, from 3.75% to 2.00%, and has since entered a cautious pause. Inflation has converged toward 2%, while core inflation remains at 2.4% and GDP growth hovers around 1%. Bank lending, which contracted for five consecutive quarters, has stabilized, and excess liquidity has been reduced from €4.7 trillion to €2.6 trillion. However, the resilience of service inflation and wage growth above 3% suggest that the scope for further rate cuts is exhausted. Instead, monetary policy has shifted its focus toward balance sheet normalization, with the ECB reducing its Asset Purchase Program (APP) by roughly €30 billion per month. In the medium term maintaining rates around 2% would be reasonable, supporting activity while remaining consistent with the ECB’s price-stability mandate. Should core inflation remain sticky, a modest rate hike could reassert control and anchor expectations without disrupting recovery dynamics.

From restriction to pause: Eight cuts and a waiting period

In just over three years, the European Central Bank’s monetary policy has gone from the most intense tightening in its recent history to a prolonged and calculated sequence of cuts. After raising the deposit rate to 3.75% in 2023 to contain an inflationary outbreak that threatened to unanchor expectations, the Governing Council embarked on a normalization process in 2024 that reduced rates eight consecutive times by 25 basis points, bringing them to 2.00% in June 2025. With this, the ECB brought an end to a period of extraordinarily restrictive policy and entered a phase of fine-tuning, aware that the transmission of its decisions had become more complex and non-linear.

The shift was motivated by sustained disinflation, which brought the overall rate back to around 2%, but also by the realization that the cumulative restrictive momentum was beginning to visibly weigh on activity. Bank lending to the private sector had contracted for five consecutive quarters, and loan surveys pointed to a significant tightening of lending standards. At the same time, business investment was slowing, and private consumption was showing a weak recovery, sustained more by improved purchasing power than by cheaper credit.

As the delayed effects of the 2022–2023 rate hikes materialized, the ECB adjusted its diagnosis from excess demand to a risk of stagnation. The elasticity of inflation to interest rates declined, and internal models began to reflect greater sensitivity in activity than in prices. This asymmetry justified the cuts in 2024 and 2025. But the latest data suggest that the room for maneuvering has narrowed. Bank lending has stopped falling, consumption is slowly rebounding, and nominal wages continue to grow above productivity. Services inflation —which is more dependent on labor income— remains above target and shows a rigidity that limits the scope for further stimulus.

In this context, further rate cuts would be of little economic use. The cost of money is no longer the main brake on activity, and additional monetary policy easing would tend to concentrate its effects in the financial sphere. Further easing could weaken incentives for fiscal consolidation by artificially alleviating public debt servicing just as European fiscal rules come back into force. At the same time, prolonging an environment of low-cost financing could reactivate the search for returns with excessive risk and reproduce the valuation distortions observed during the quantitative easing phase.

The ECB is aware of this dilemma. Therefore, the current pause is not a response to indecision, but rather a prudent assessment of the symmetrical risks: that of doing too little in the face of a possible inflationary upturn, and that of doing too much in the face of an economy that is barely sustained by domestic demand. In terms of macro-financial balance, the 2% deposit rate seems a reasonable starting point today: low enough to avoid further cooling of the economy, but not so low as to undo the credibility gained over the last two years.

The new center of gravity: Balance sheet policy

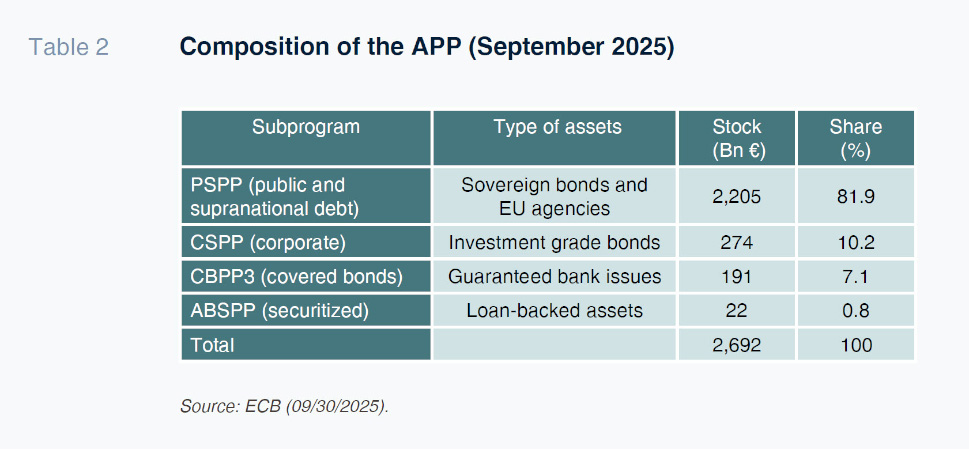

Stable rates do not equate to inaction. Since 2023, the European Central Bank has shifted the focus of its strategy from the price of money to balance sheet management, making the reduction of extraordinary liquidity its main instrument of normalization. The approach has been deliberately gradual: allowing bonds purchased under the Asset Purchase Program (APP) and the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) to mature without reinvesting the principal, thereby absorbing liquidity without abruptly altering financing conditions.

The process has involved a change in the operating regime. For almost a decade, European monetary policy was based on balance sheet expansion and abundant reserves. Now, the ECB is seeking to reintroduce relative scarcity into the system to restore the role of the deposit rate as an effective market benchmark. From its peak in 2022, the total volume of assets purchased has fallen from just over €3.2 trillion to €2.69 trillion in September 2025, with a reduction rate of around €30 billion per month.

This quantitative adjustment has both financial and fiscal implications. On the financial side, the ECB’s gradual withdrawal as a net buyer returns the spotlight to private investors and revalues sovereign risk premiums, favoring a more efficient allocation of capital. Fiscally, it means that governments will have to return to full market financing, without the implicit cushion provided by central bank reinvestments. At the same time, lower liquidity in the system is forcing banks to manage their reserve and collateral positions more actively, revitalizing the interbank market after years of lethargy.

The ECB is applying a passive reduction: it is not reinvesting maturity but is avoiding active sales that could put pressure on the markets. This strategy minimizes dislocations, although it prolongs the central bank’s presence in sovereign debt. In the medium term, the dismantling of the APP will be the centerpiece of the return to a regime of scarcer liquidity and market rates with greater informational content.

Why lowering rates would be ineffective... and potentially harmful

The current level of 2% on the deposit facility cannot be considered strictly neutral, but it does represent a transitional balance between price control, financial stability, and sovereign debt sustainability. It is a point of support that allows inflation expectations to remain anchored without stifling growth or creating unnecessary tensions in debt markets. After a cycle of eight consecutive cuts, the ECB has reached a level of rates at which the marginal effects of further reductions would be increasingly weak and potentially counterproductive.

There are two reasons for this. On the one hand, the transmission to private credit has lost sensitivity: demand for corporate financing now depends less on marginal financing costs and more on profitability prospects and the degree of confidence in the recovery. Households, for their part, have already adjusted their spending and mortgage decisions to current interest rate levels. Therefore, a further cut would be unlikely to translate into more investment or consumption, but rather into a reallocation of risks within the financial system.

On the other hand, the public sector would become the main beneficiary of any new stimulus. With sovereign yields at historically low levels, a further decrease in the cost of financing would ease the debt burden just when fiscal policy should be geared towards consolidation. Lowering rates in this environment would be tantamount to subsidizing public debt, delaying budgetary adjustments and eroding the separation between monetary and fiscal policy. This externality is particularly sensitive in a monetary union with 20 national treasuries and a single monetary authority.

Furthermore, a lower interest rate environment would reopen the financial distortions that the ECB has been trying to correct over the last two years. The search for returns on higher-risk assets, the overvaluation of certain segments of corporate debt, and the artificial compression of bank margins would reappear. The experience of the 2016–2019 period shows that prolonging ultra-expansionary policy ultimately reduces the efficiency of the banking channel and creates structural dependencies that are difficult to reverse.

The ECB is aware of this delicate balance. The current pause reflects a cautious assessment of the risks of moving in either direction. On the one hand, further easing could generate broader stability risks than marginal macroeconomic benefits. On the other hand, keeping rates stable while wages and services remain somewhat rigid could be insufficient to ensure definitive convergence towards the 2% target.

In this context, a moderate upward adjustment —if core inflation persists or labor costs continue to accelerate— should not be ruled out. A symbolic increase would reinforce the ECB’s anti-inflationary credibility without significantly deteriorating financing conditions or threatening the recovery. Ultimately, the pause does not imply a downward bias, but rather the opening of a waiting period to decide in which direction the true medium-term equilibrium lies. Monetary normalization, rather than a linear trajectory, thus becomes a process of continuous calibration, where prudence is the most sophisticated form of action.

2% as an operational range and anchor of credibility

2% has established itself as the operational benchmark for the new phase of European monetary policy. At this level, bank margins have stabilized, and monetary policy transmission is once again relying on conventional channels, without the need for extraordinary measures. Credit to the private sector has stopped falling, but has not rebounded significantly, suggesting that monetary policy still has a slight but effective restrictive bias.

From a fiscal and financial perspective, 2% represents a fragile equilibrium point. Lower rates would once again encourage public borrowing and weaken budgetary discipline just when fiscal policy needs to take on a more restrictive role. Higher rates, on the other hand, would put pressure on national finances —especially in the periphery— and could fragment monetary transmission.

Overall, the current level allows for consistency between price stability, fiscal sustainability, and financial stability. This is not a neutral rate, but rather a compromise range, in which the ECB can maintain inflation convergence toward the target without reopening financial or fiscal imbalances. The challenge will be to determine how long this balance can be sustained without wage inertia or public spending rigidity forcing a further upward adjustment.

Risks and asymmetries

Core inflation is proving more resilient than expected, especially in the services component. While industrial goods and energy have moderated their advance thanks to the normalization of supply chains and the adjustment of wholesale prices, nominal wage growth —above 3% year-on-year in the euro area— is keeping domestic price pressures alive. This gap between wages and productivity suggests that the disinflation process may have reached its final stage: inflation is no longer falling due to supply shocks but depends on the moderation of demand and the ability of companies to absorb costs without passing them on to prices.

At the same time, long-term debt yields have rebounded slightly since the summer. The German 10-year bond remains at around 2.6%, compared to 2.3% at the beginning of the year, while the Italian bond is around 4%, widening the north-south spread once again. This movement reflects less a loss of confidence in the ECB than a normalization of the debt market following the reduction of the APP and the gradual disappearance of its anchoring effect. The yield curve has steepened moderately, a sign that investors are discounting a prolonged equilibrium in rates in the current environment, but with a latent risk of an inflationary rebound if wages or energy prices become entrenched.

The global context adds complexity. Persistent geopolitical tensions are putting upward pressure on industrial prices and international logistics. Although headline inflation has moderated to 2%, the structural factors that fueled its rebound in 2022 have not entirely disappeared. In this regard, the ECB faces an unstable balance: too loose a policy could reignite pockets of imported inflation, while an overly restrictive one could exacerbate the deterioration in credit and investment.

On the other hand, the process of draining liquidity is changing the operating conditions of the money market. After more than a decade of abundant reserves, the Eurosystem is approaching a regime of scarce reserves, where competition for collateral and remunerated reserves may cause occasional episodes of volatility in interbank rates. The ECB is already working on a technical redesign of the operational framework, adjusting the interest rate corridor and recalibrating term operations to avoid dislocations. In practice, liquidity management has become the new fine-tuning instrument of the ECB: a structural change from the previous paradigm based on interest rates and asset purchases.

Finally, national divergences continue to condition the transmission of monetary policy. The northern economies —Germany, the Netherlands, Austria— with a greater weight of fixed-rate loans and lower public debt, absorb changes in official rates better. In contrast, the southern economies —Spain, Italy, Portugal, Greece— where variable-rate loans predominate and public debt is high, are much more sensitive to each adjustment. This heterogeneity limits the ECB’s room for maneuver and requires extremely cautious calibration. The central bank must act with almost surgical precision: firm enough to preserve credibility, but flexible enough not to fracture the financial cohesion of the Eurozone.

Medium-term outlook (2026–2028)

The baseline scenario envisages that the ECB’s official rates will remain stable for much of 2026, at around the current deposit rate of 2%, accompanied by a gradual reduction in the volume of the asset purchase program (APP). This projection reflects the convergence of headline inflation towards 2%, moderate growth in the euro area, and the fact that monetary policy has already undergone a significant cycle of cuts. In this context, the ECB appears to have reached an operational "pivot point" where a further rate cut would offer limited marginal improvement and would therefore prioritize consolidating balance sheet normalization.

However, risk analysis suggests that the next move in the medium term may not be downward. If inflation —and especially its underlying component— stabilizes somewhat above 2% during 2026, and if wages and service prices maintain an accelerated dynamic, the ECB could consider a moderate rate hike. This action would be aimed not so much at punishing growth as at reinforcing anti-inflationary credibility: demonstrating that the pause does not imply complacency, but vigilance. In addition, as it rises, the financial cost of public debt would once again reflect a more realistic risk premium, which would adjust the fiscal incentive towards consolidation and reduce dependence on monetary policy to sustain government financing.

At the other extreme, if the external environment deteriorates —for example, a global slowdown, a sharper fall in oil prices, or a sharp slowdown in international trade—inflation could fall below the ECB’s target. In that case, the door would be open to a technical downward adjustment of rates, although the central bank currently seems more inclined to modulate the pace of balance sheet reduction than to resort to further rate cuts. This preference reflects the recognition that monetary transmission is less effective than in the past and that quantitative policy (balance sheet) could offer greater flexibility to ease conditions without sending signals of a change in cycle as visible as a fall in rates.

The main challenge for the ECB will then be to maintain a balance between three simultaneous objectives: the orderly withdrawal of quantitative support (liquidity and asset portfolio), the preservation of homogeneous financing conditions throughout the euro area, and the safeguarding of monetary policy credibility. In this regard, the institution seeks to rebuild a policy framework in which the deposit rate once again becomes the main transmission instrument, and the balance sheet —which has been large over the last decade— regains its role as a secondary buffer. This shift in emphasis implies that the ECB is less willing to move rates as a first response and more prepared to use liquidity mechanisms and asset maturities as leverage for adjustment.

Conclusion

The cycle of eight cuts has served its essential purpose: to contain inflation without undermining confidence in the currency or in the ECB’s ability to manage it. But the scope for further rate cuts has been exhausted. From now on, stability —or even a slight tightening— appears to be the most effective way to consolidate the central bank’s credibility and allow debt markets to regain their disciplinary function, lost during years of monetary interventionism.

The next chapter in ECB policy will not be written in interest rates, but in balance sheet management. Its success will depend on the ability to reduce the central bank’s footprint in the markets without eroding control over inflation or jeopardizing the financial cohesion of the eurozone. If it succeeds, the euro will have left behind the era of monetary exceptionalism and will return to a framework of normality in which price stability, fiscal prudence, and market autonomy once again sustain each other.

Funcas Finance and Digitalization Department