The UK’s EU referendum: Implications for the UK, EU & Spanish economies

Brexit is likely to have a negative impact on the UK economy. While some offsetting opportunities exist, the shockwaves from losing its second largest economy would be felt in the EU, as well as in Spain, where people flows and financial connections with the UK are especially significant.

Abstract: The UK’s referendum on whether to remain a member of the European Union has economic and political implications that extend beyond its borders. Polls suggest arguments related to the economy and immigration will play a key role in determining voter preferences. A vote in favour of leaving the EU (“Brexit”) is likely to have a net negative impact on the UK economy, although the long-term implications will depend on the extent to which the UK´s trade relations with the EU are permanently altered and whether the UK is able to take compensatory action. Brexit could also create significant economic spillovers for the EU, as well as call into question the wider EU project. The Spanish economy is not immune and, unlike most other EU economies, runs both a goods and services surplus with the UK. People flows – both tourism and migration – as well as financial interlinkages are particularly strong between both countries.

Introduction

On June 23rd, the UK will hold a referendum to decide whether to remain a member of the European Union. As the EU’s second largest economy, a decision by the UK to leave (“Brexit”) could have far reaching economic implications both for the UK and the wider EU. In this article, we review the main factors likely to determine the outcome of the result and the potential economic implications both for the UK and wider EU economy. We conclude by focusing on the links between the UK and Spanish economies.

Factors influencing the outcome

The UK referendum on membership of the European Union looks set to be a close run affair. Opinion polls point to a narrow difference in support for remaining and leaving, with around 15-20% of voters still undecided. This contrasts with financial markets, which hold a more sanguine view about the prospects of the UK staying in the EU.

The debate over the UK’s EU membership is a proxy for a wider discussion around the costs and benefits of globalisation. The UK is particularly exposed to globalisation with an open economy that has pursued a largely pro-market, liberal economic agenda.

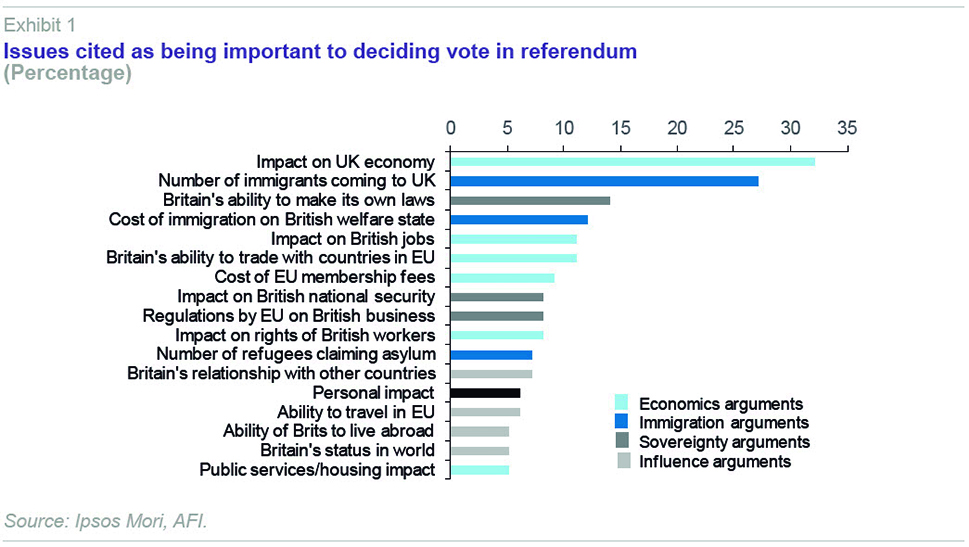

Opinions polls suggest that four main groups of arguments will play a key role in determining how voters will cast their vote. These include economic arguments relating to whether the UK economy and individuals’ personal economic situation will be better or worse off outside or within the EU. Immigration arguments as to whether the UK would have greater or lesser ability to control inward migration from inside or outside the EU. Sovereignty arguments concerning whether the UK will be able to have more or less control over policy affecting the country inside or outside the EU. And influence arguments regarding whether the UK’s voice will be stronger inside or outside the EU.

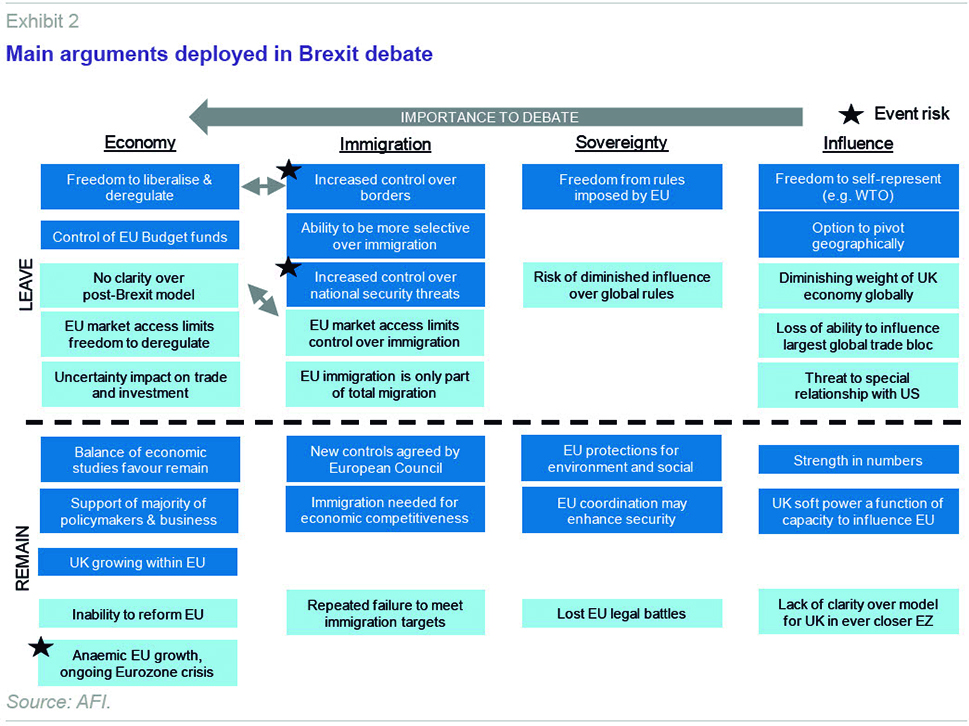

Polls suggest that economic and immigration arguments are disproportionately more important to voters in determining how to cast their vote and therefore form the battleground for the current Brexit campaign. The exhibit below summarises the main arguments deployed by remain and leave campaigners.

The principal challenge for the remain campaign is to motivate voters to turnout in favour of supporting a status quo that many consider to be imperfect. Instead of exhalting the merits of the European Union, the remain camp is therefore focusing its attention on highlighting the economic risks associated with leaving the EU (“project fear”).

By contrast, the leave campaign faces the challenge of spelling out a coherent alternative that would improve the UK’s overall position relative to the status quo. Advocates of leaving the European Union focus on the (hypothetical) increased freedom the UK would have to control immigration flows, as well as to eliminate unwanted EU regulation, agree free trade deals and repatriate UK contributions to the EU Budget.

Economic implications for the UK

The interaction of these arguments is captured in the large number of economic studies that have been published in recent months analysing the potential impact of Brexit on the UK economy.

These studies conclude that short-term uncertainty in the run up and immediate aftermath of Brexit will be negative for the British economy by undermining confidence, postponing investment decisions and creating significant financial volatility.

In the medium term, financial volatility could have increased real economy implications as tougher financing conditions and lower confidence feed through to activity and economic agents face heightened uncertainty (e.g., regarding trade rules).

However, the longer-term implications will depend on the extent to which the UK’s trade relations with the EU are permanently altered and whether the UK is able to take compensatory action (e.g. via deregulating, repatriating EU Budget funds and agreeing free trade deals with other regions). This will ultimately determine the impact on long-term growth and competitiveness of the UK economy.

Underpinning these conclusions is the trade-off that the UK would face between increasing its freedom of action and retaining access to EU markets. The EU accounted for around 44% of total UK exports of goods and services in 2015.

As set out in the previous table, those countries that have the highest degree of access to EU markets, such as Norway, are required to abide by the majority of EU rules, including accepting freedom of movement of people and contributing to the EU Budget. At the same time, they have significantly less influence over the formulation of these rules.

Other countries with bilateral trade deals with the EU, such as Switzerland, Canada or Turkey, fall within a spectrum – with increased freedom of movement offset by reduced access to EU markets. At the extreme end is WTO membership where the UK would be largely free of EU rules but subject to EU tariffs and customs costs.

Overall, the balance of economic analysis would look to be supportive of the remain campaign, which has been further reinforced by economic warnings made by various international organisations, such as the IMF (2016) and the OECD (2016). By contrast, the leave campaign faces a challenge to spell out an alternative model which would minimise economic costs from reduced access to EU markets while also increasing the UK’s freedom to act.

Implications for the EU

The economic and political implications of a UK exit from the EU extend beyond the loss of a member state representing 17.6% of the EU’s GDP. Several channels of impact can be identified, which would affect EU member states by varying degrees:

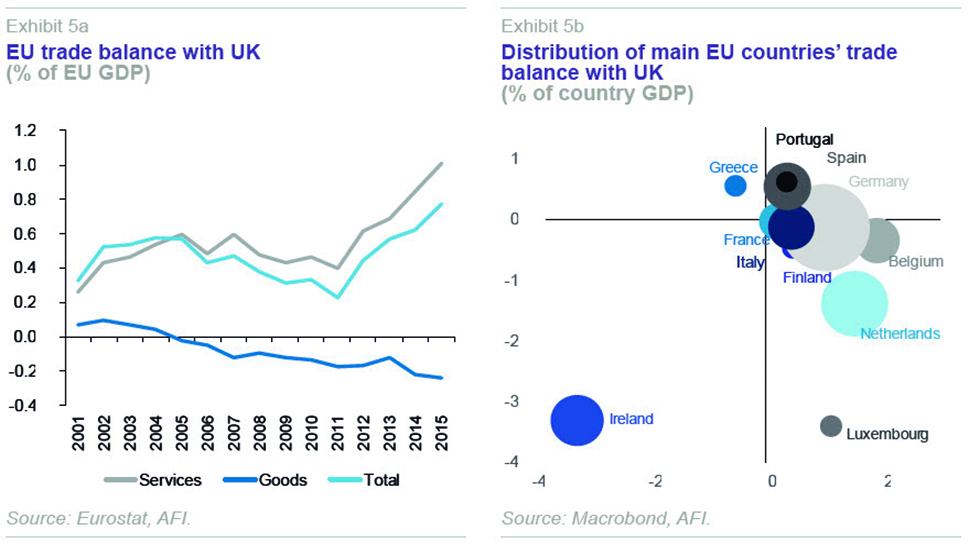

- Trade channel: The EU runs a trade surplus with the UK of around 0.8% of EU GDP. The surplus is sustained by UK demand for goods, while the EU has a deficit with the UK on services, primarily due to the UK’s strength in financial services.

In the short-run, Sterling depreciation and lower confidence of UK consumers could affect the UK’s demand for imports from the EU. Longer term, any trade deal that introduces tariffs and non-tariff barriers would undermine trade flows between both economies with negative implication for both sides (albeit more pronounced for the UK given that the EU accounts for 44% of UK exports while the UK accounts for around 16% of EU goods exports). Over time, other EU economies may be able to substitute for UK exports, especially in the services industry – though potentially at a higher cost.

- FDI channel: The UK is the number one destination for inward FDI from the EU with one half of all European headquarters of non-EU firms in the UK –according to the UK government (HM government, 2013). It is also one of the primary markets for outward FDI by EU member states, particularly in motor trade, utilities and mining and quarrying.

Sterling depreciation and lower confidence could undermine remittances from EU investments in the UK and could create contagion risks in the event of a contraction in UK GDP. Longer-term the UK’s attractiveness as a FDI destination could be negatively affected. A recent CEP (See references) study estimated that leaving the EU could reduce FDI inflows by around 22%. However, the ability of other EU economies to attract inward FDI will also depend on the extent to which the UK attempts to compensate (e.g., via lower regulation and taxation). Brexit could also reduce the attractiveness of the EU market as a whole for foreign investors.

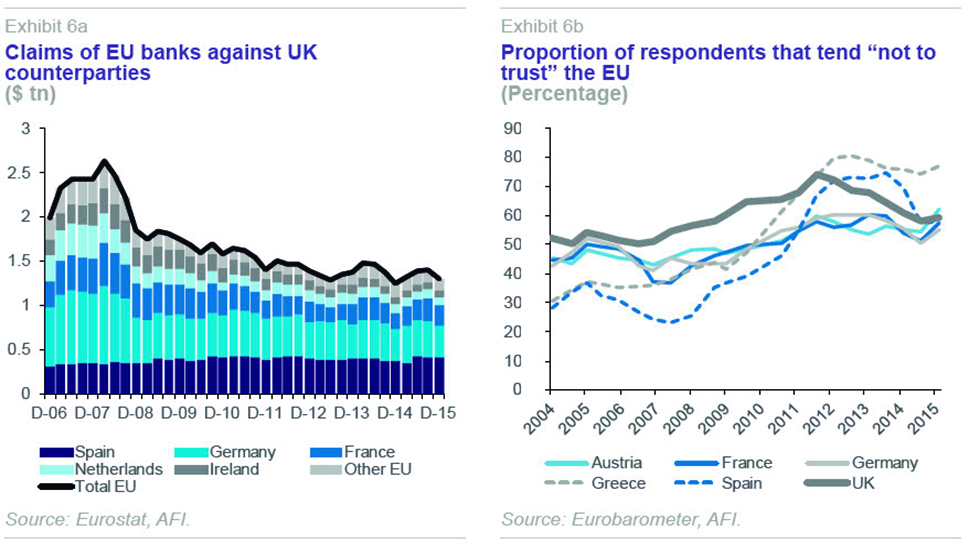

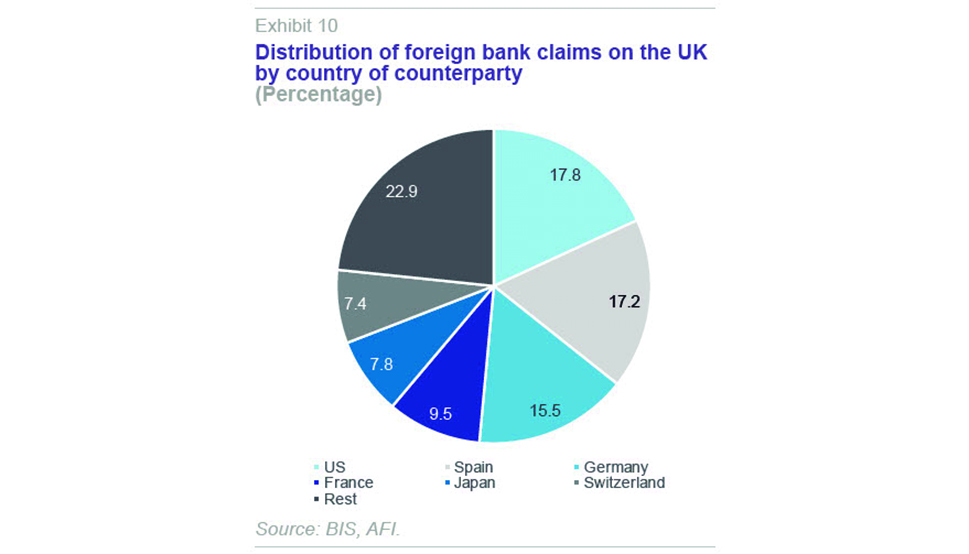

- Financial channel: EU banks have over $1.3 trillion in claims against the UK banking sector according to Bank of International Settlements data. The UK is also a key financial hub for wholesale and large cap financing of EU enterprises. 78% of EU foreign exchange trading takes place in the UK.

EU banks exposed to the UK could face contagion risks via an increase in the NPL ratio and lower contributions to their income statements from UK operations. In a scenario of an extreme GDP correction, downstreaming of capital to UK entities could also be required. Longer-term, other EU financial capitals such as Frankfurt and Paris may look to compete with London, especially if the UK is no longer able to offer a passport allowing third country financial institutions automatic access into the EU. However, replicating London’s financial sector ecosystem (legal, IT, etc.) will not be straightforward and may result in a short-term increase in financing costs for EU firms. Cross border banks could be affected by diverging regulatory requirements.

- Strategic considerations: The UK enjoys significant soft and hard power. According to Elcano (2015), the UK is the country that contributes most to the EU’s global projection. It has the fifth largest defence budget after US, China, Saudi Arabia and Russia. The UK is also a net contributor to the EU Budget and an important member of the liberal bloc within the EU. Brexit could reduce the ability of liberal minded economies to influence EU policy potentially resulting in a more interventionist approach.

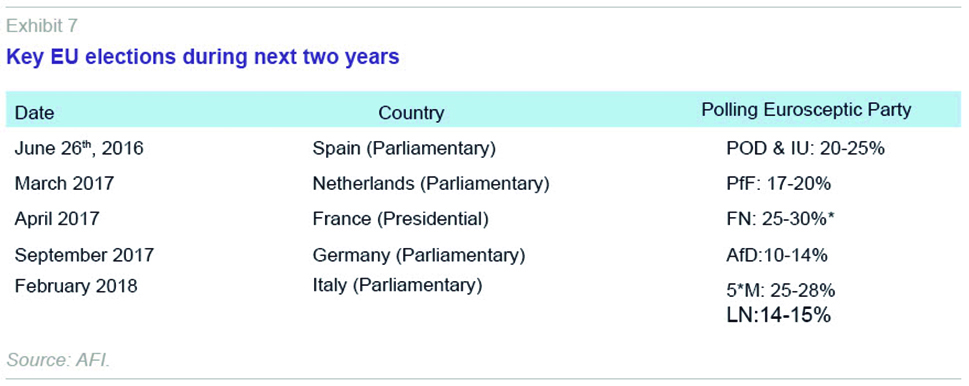

- Political considerations: Finally, with dissatisfaction levels with the EU rising in core and peripheral economies alike, Brexit could serve as an example for other countries to follow suit. In this regard, the rise of Eurosceptic parties in a number of EU countries could provide a vehicle through which other member states may seek to carve out their own arrangements with the EU or even pursue referenda. On the flipside, a UK exit could spur greater integration, especially in areas where the UK resistance has previously been a hurdle e.g., social policy.

UK-Spain links

Spain is not immune from the effect of Brexit with particularly strong links to the UK in terms of people flows (tourism and migration) and financial sector interlinkages.

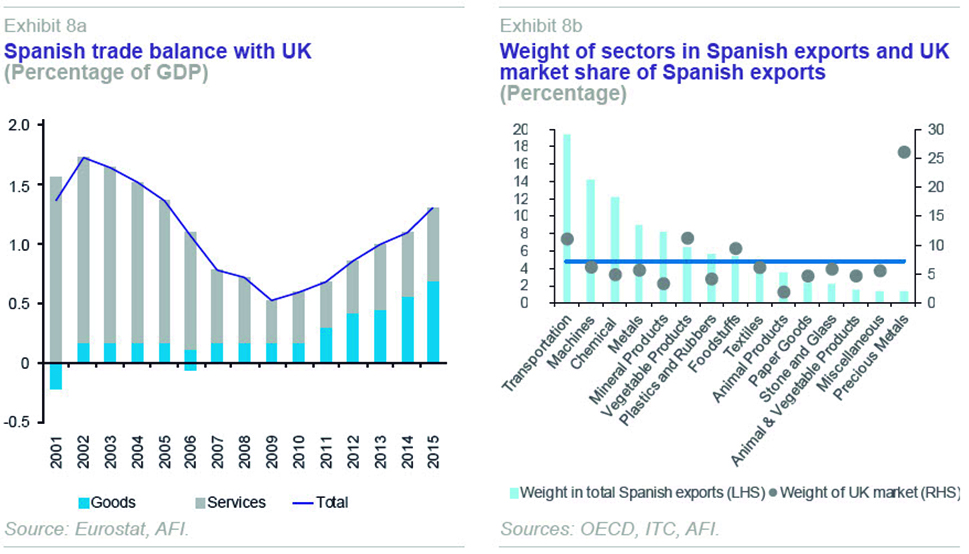

The Spanish economy runs a trade surplus with the UK worth 1.3% of GDP. Unlike most other EU economies, Spain has both a goods and services surplus. The UK is the fourth most important market for Spanish goods exports, accounting for 7.3% of the total. The UK is also a particularly important market for Spanish exports of transport goods (cars, trains, airplanes) as well as food (fruit and vegetables).

Spain’s services surplus reflects the large inflows of British tourists to Spain. The UK is the number one market for Spanish tourism services, receiving 15.8 million individual visits last year, which accounted for 21.1% of total tourism spending last year.

Migration flows between the two countries are also significant, albeit with different profiles. An estimated 800,000 to 1 million British nationals live in Spain at least part of the year. This population is heavily skewed towards older age groups with an elevated dependence on the social security system. These groups could be vulnerable to a Brexit scenario which might limit the access of UK citizens to EU health systems. Meanwhile the UK is the primary destination for Spanish migrants, though these are mainly younger and focused on seeking employment opportunities.

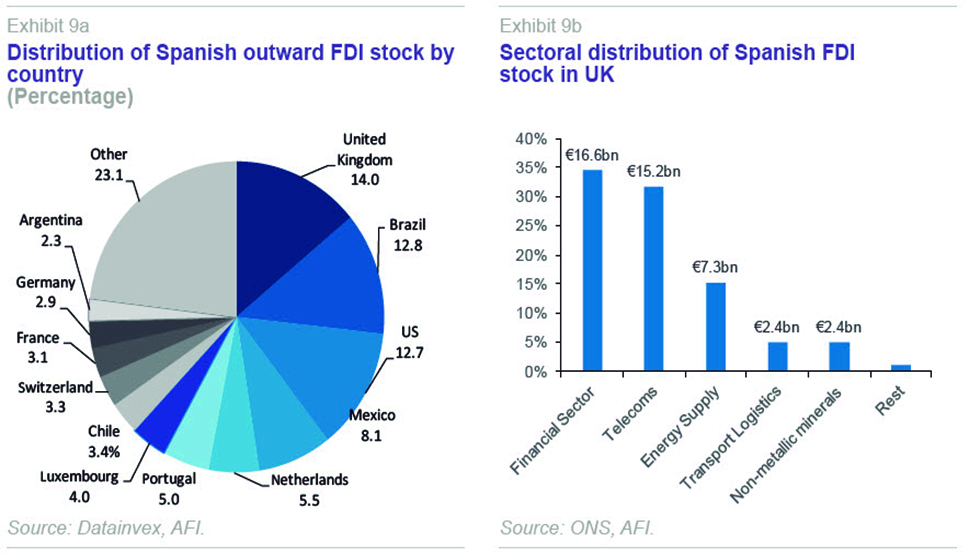

The UK is the first destination for Spanish outward foreign direct investment accounting for 14% of total Spanish outward FDI. Spanish investments are particularly focused on the financial sector, telecommunications and energy supply. Meanwhile, the UK is the fifth largest investor in Spain with major investments in telecommunications and tobacco.

Spanish investment in the UK financial sector is particularly important. The Spanish banking sector holds the largest claims against the UK private sector of all European countries, second only to the US. The subsidiary models employed by the banks with the largest exposure should provide some degree of insulation against adverse shocks associated with a Brexit event.

Summary and conclusions

Arguments relating to economics and immigration will play a key role in determining whether UK voters decide to remain in the European Union. In this article we have focused on the economic implications of Brexit both for the UK and the EU. The balance of economic studies points to a negative impact of Brexit for both the UK and the EU.

Some offsetting opportunities exist for both sides, but for the UK these will be constrained by the need to retain a high degree of access to EU markets. The shockwaves of losing its second largest economy will be felt in the EU, as well as in Spain where people and financial connections with the UK are especially important.

References

CEP Brexit Analysis No. 3, The impact of Brexit on foreign investment in the UK.

ELCANO (2015), Global Presence Report 2015.

HM GOVERNMENT (2013), Review of the Balance of Competences between the UK and the EU: The Single Market, July.

HM TREASURY ANALYSIS (2016), The long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives, April.

IMF (2016), World Economic Outlook, April.

OECD (2016), The Economic Consequenes of Brexit: A Taxing Decisions, April.

Nick Greenwood. A.F.I. – Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.