Spain’s public accounts: Analysing stability and sustainability

Spain´s recent fiscal slippage is raising concerns over long-run fiscal and debt sustainability. Reforms of Europe’s fiscal rules, along with improvements to Spain´s internal fiscal framework, will be necessary to ensure consolidation.

Abstract: Despite strong economic growth (3.2%), the Spanish government ran a deficit of 5.1% of GDP in 2015. This result implies falling short of both European and internal fiscal targets. Recent fiscal slippage, together with increased public debt since the start of the crisis, are casting doubt on Spain’s ability to restore its budgetary equilibrium and ensure debt sustainability. The biggest difficulties are apparent in the regional governments and social security system. Correcting these imbalances is a general economic policy problem that will require reforms.

The economic climate for the general government was favourable in 2015. Real-term GDP growth was 3.2%, basically driven by the pick-up in domestic demand (Laborda and Fernández, 2016). Nevertheless, the public deficit reached 5.1% of GDP, exceeding the budgetary stability target and deviating from the path laid down by the European Commission under the Excessive Deficit Procedure by eight tenths of a percent.

[1] Economic growth and the public deficit are two interrelated variables, such that the favourable performance of one is partly due to poor performance of the other.

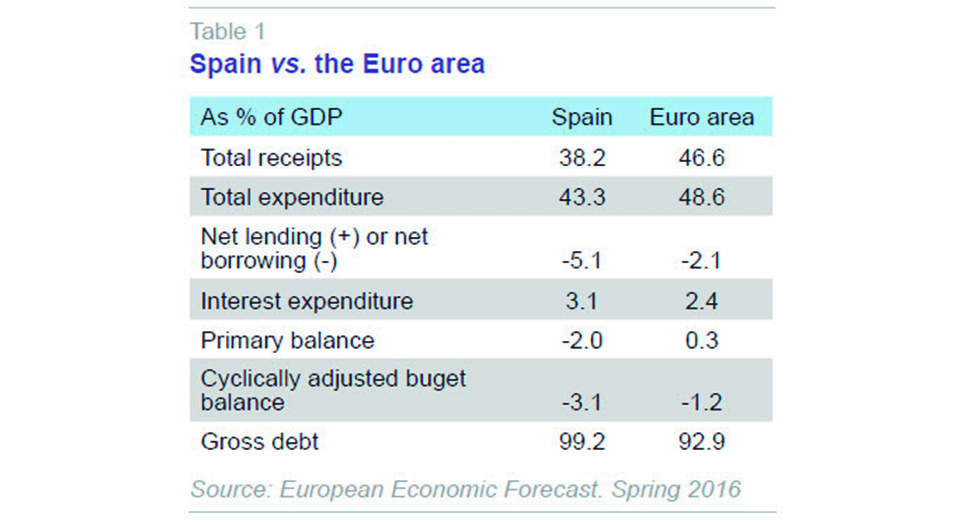

In comparison with its euro area partners, Spain has less public sector revenue (8.4 points), less expenditure (5.3 points) and a clearly higher observed deficit (Table 1). The cyclically adjusted deficit (3.1% in Spain) is almost three times the euro-area average (1.2%), and it is above average in terms of the ratio of public debt to GDP.

Net borrowing requirement

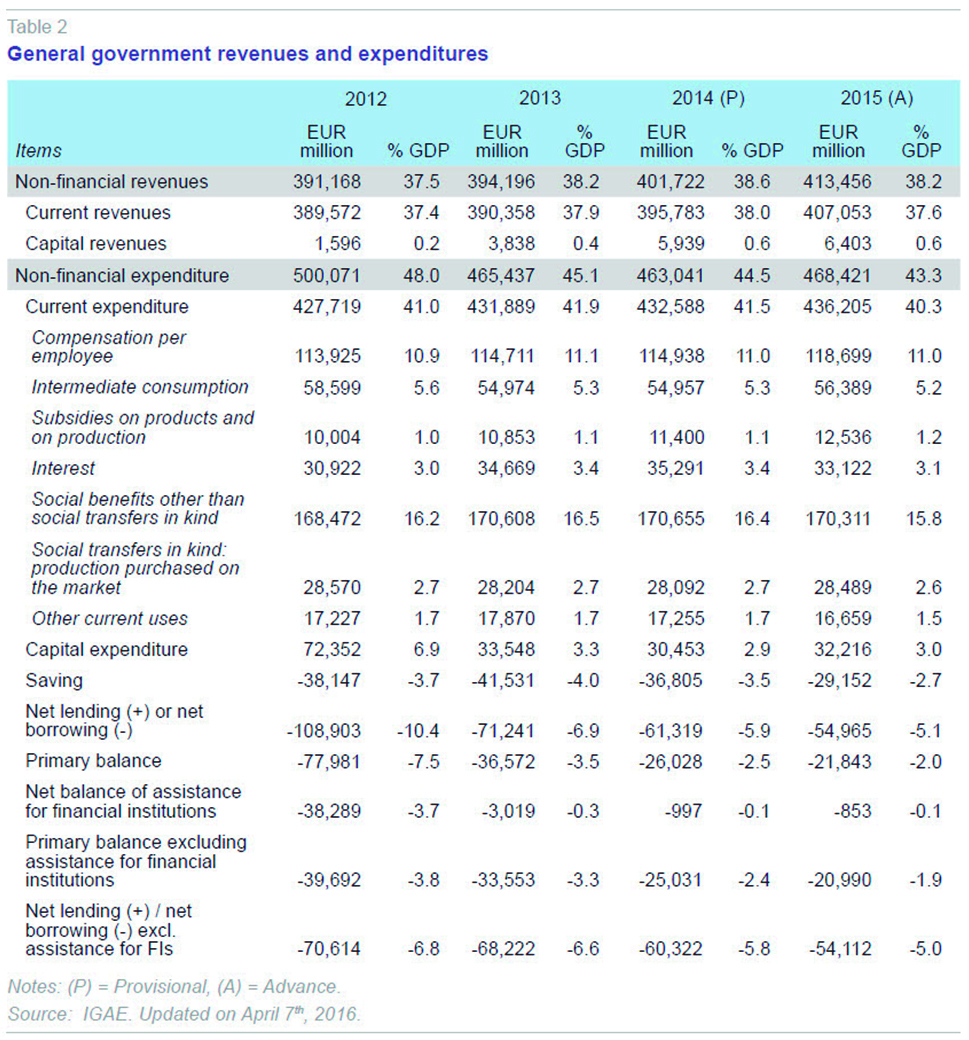

Table 2 shows the main items of the Kingdom of Spain’s public accounts between 2012 and 2015. The net borrowing requirement has gone from 6.8% to 5% of GDP. The rate of fiscal consolidation since the Spanish economy began to grow in 2014 has been around 0.8 points a year. This rate is too slow, at least as far as the European Union is concerned, as the excessive deficit procedure aims for Spain’s need for financing to fall below 3% in 2017, according to the stability programme update the government has just presented.

[2]

Deficit reduction has been achieved with an increase in income of 0.7 points of GDP (22,288 million euros more) and a reduction in expenditure (excluding financial support) of 1 point (although non-financial expenditure increased, albeit by just 5,786 million euros). Reduced spending meant capital uses dropped by 0.3 percentage points (excluding financial support). Current expenditure has fallen by 0.7 percentage points since 2012, of which 0.3 points was from public consumption (including salaries) and 0.4 from monetary social transfers (including unemployment benefits).

Table 2 shows some other significant data. Firstly, the primary balance (excluding support for financial institutions) went from -3.8% of GDP to -1.9%, and was still negative at about 20,990 million euros in 2015. Interest expenditure alone represents 3.1% of GDP, such that the recent cut in interest rates due to the European Central Bank’s monetary policy helps Spanish public accounts (in 2014 interest expenditure was 3.4% of GDP).

Secondly, saving – defined as the difference between current revenues and current expenditures – remains negative at 2.7% of GDP, having improved one percentage point since 2012 (3.7%). These data show that Spain’s general government is financing its expenditure on service delivery and income transfers with debt. This is an unsustainable situation over the medium term and makes Spain’s public services highly vulnerable in the event of possible market turbulence.

Finally, uses of capital,

i.e., public investment, whether direct or through other agents, came to 2.9% of GDP in 2015. This spending item was drastically cut in the early years of the crisis, as in 2007, public investment had reached 5.9% of GDP. The current volume of public investment is somewhat less than that of the euro area, although there does not seem to be a need to return to pre-crisis levels.

[3] Nevertheless, capital expenditure has grown for the first time, 5.8% higher than in 2014.

To get a more accurate view of Spain’s public accounts, it is necessary to analyse each of the country’s constituent levels of government.

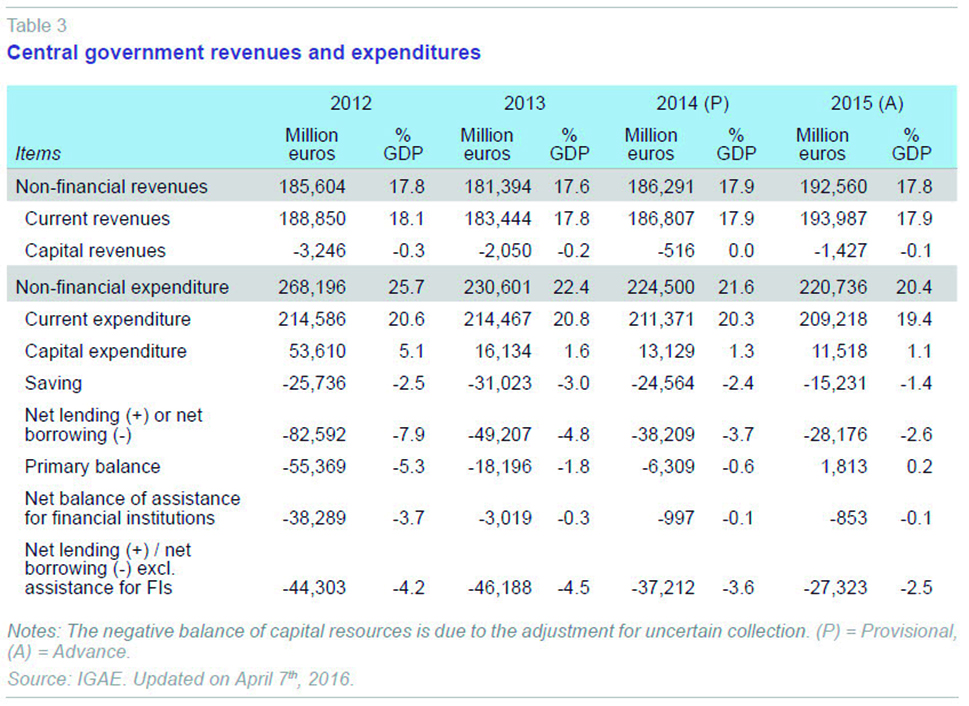

a) Central governmentHalf of Spain’s public deficit in 2015 originated in the central government level and its autonomous agencies. However, the need for financing has dropped almost by half since 2013, which is explained by the reduction in expenditure (income remained constant in GDP terms). In particular, since 2013, total expenditure has dropped by 2 points of GDP from the 1.1 due to the reduction in transfers to other levels of government and bodies (autonomous regions, local authorities, and the social security system). The positive note in the case of the central government is that in 2015, it managed to obtain a primary surplus for the first time since the start of the crisis. However, the savings rate is still negative, indicating that current income remains somewhat inadequate.

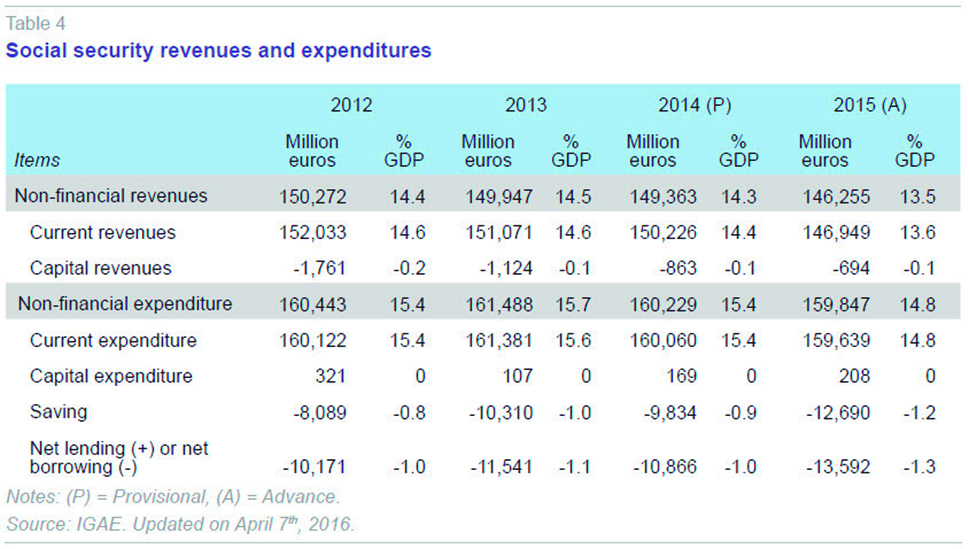

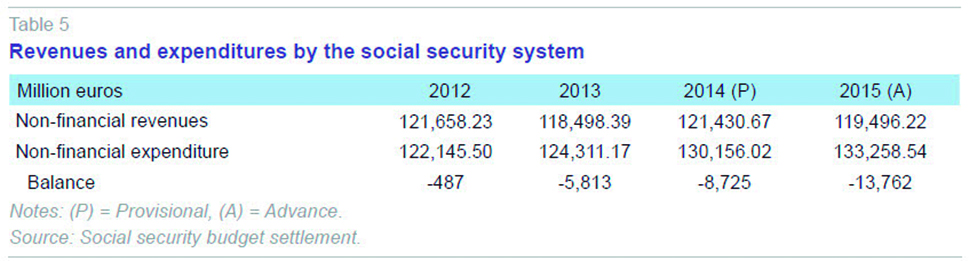

b) Social securityFor their part, the social security funds have a deficit of over 1% over the four-year period, reaching 1.3% in 2015 (Table 4).

The social security account includes both spending on unemployment benefits and pensions. The National Accounts for 2015 do not disaggregate these two items, so to distinguish the pensions system from unemployment protection it is necessary to look at the details of budgetary execution.

[4] Table 5 presents expenditure and income recognised by the social security system, revealing that the deficit arises on the income side. This shortfall was initially caused by the drop in employment, and then, when employment began to recover, by legislative changes to reduce contributions via various formulae. Expenditure growth has been driven by the continuously rising number of pensioners and the fact that new pensions are, on average, higher than existing ones.

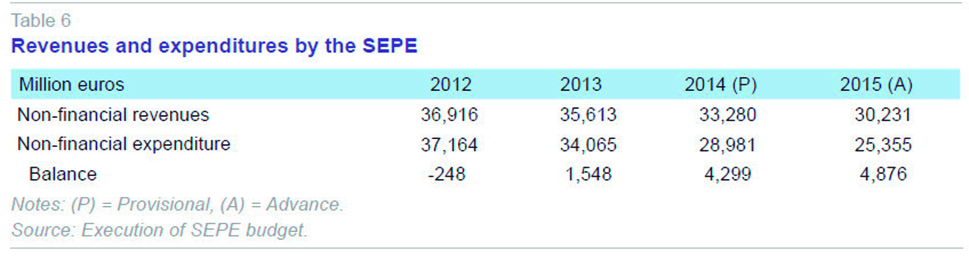

In short, the upward trend in the social security pensions´ system deficit is worrying. The budgetary execution figures show the trend in unemployment benefits to be more positive, as can be seen in Table 6. Total expenditure by the Public State Employment Service (SEPE in its Spanish initials) decreased by 12 billion euros, representing a significant saving for the public sector. The drop in expenditure has also made it possible to reduce the State’s annual contribution, which came to 10,009 million euros in 2015.

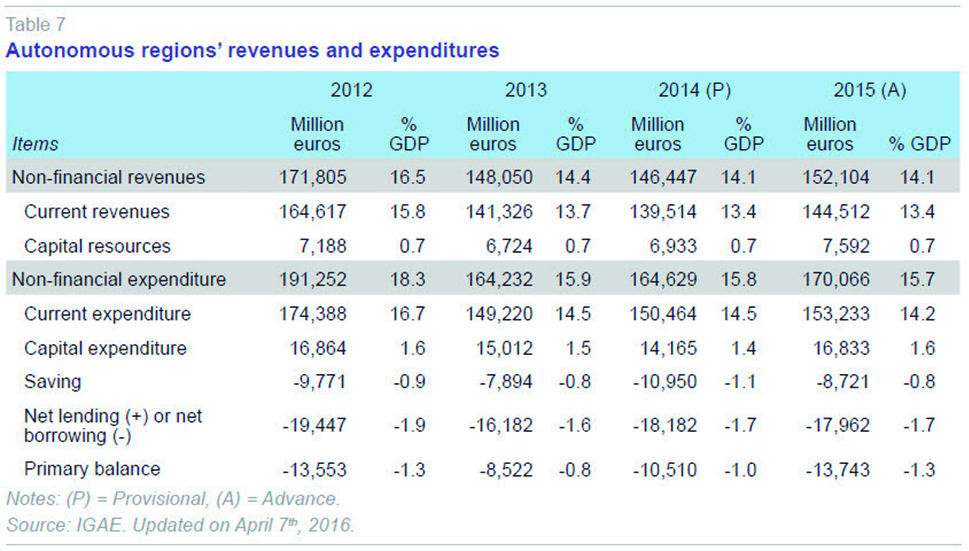

c) Autonomous regions and local governmentIn the case of sub-national governments, the autonomous regions registered a similar deficit to the previous year (1.7%), such that regional deficit shows a certain reluctance to decrease. Since 2013, the regions’ income and expenditure have decreased by 0.3 points of GDP. They also have a negative savings rate that in 2015 came to 0.8 points of GDP. The primary balance is also negative (-1.3).

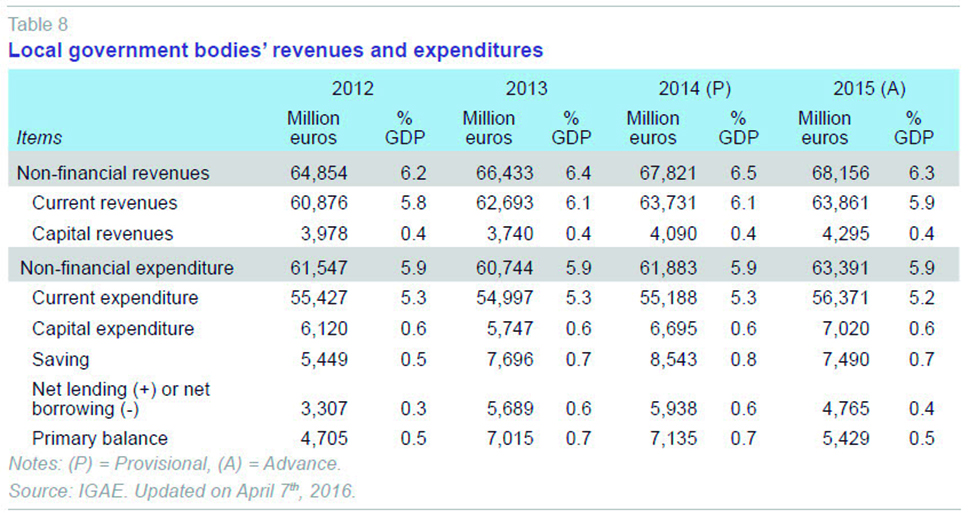

The local government appears to be in better shape, running a surplus overall, with a positive savings rate and primary surplus over the four-year period considered.

Therefore, except in the case of local government, all levels of the Spanish public sector are suffering from similar problems: current expenditure exceeds income, despite the cost of interest dropping considerably. This situation is not sustainable over the medium term, given that it can lead to continual debt growth, the variable examined in the following section.

Government debt

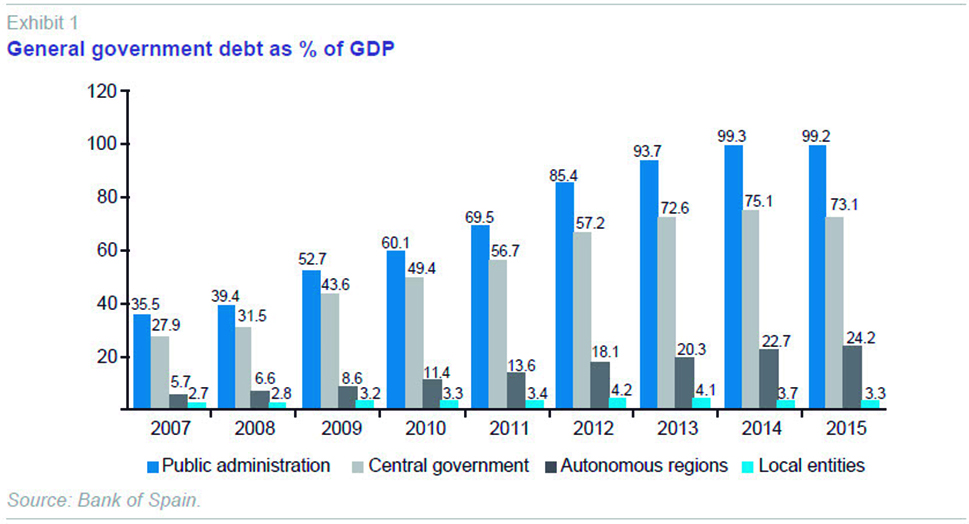

Spain’s public debt came to 99.2% of GDP in 2015, well above the euro area average (92.9%), although below that of the world’s advanced economies (see IMF, 2016). However, as Exhibit 1 shows, Spain’s debt trend and outlook are a cause for concern.

In the first seven years of the crisis, public debt almost tripled relative to GDP, and only in 2015 was a degree of stabilisation achieved, despite a borrowing requirement of 5.1%. The 0.1 percentage point reduction in the debt was achieved through the strong rise in nominal GDP (3.8%), but also thanks to the sale of assets worth 1.5% of GDP (16,269 million euros). Thus, although 2015 marked the start of a gradual reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio, primary surpluses will be needed each year, provided the interest burden does not exceed nominal GDP growth (see, for example, Maudos (2014)). It is worth noting that the autonomous regions are facing more rapid debt growth than the other levels of government, although on average their debt levels are still moderate relative to their relative share of public spending.

Noncompliance with fiscal rules

Spain has a fiscal rule enshrined in the Organic Law on Budgetary Stability and Financial Sustainability (LOEPSF in its Spanish initials), passed in 2012, implementing Article 135 of the Constitution.

[5] The legislation establishes annual budgetary stability targets, and expenditure and debt rules for all public sector entities. In aggregate terms, the first two were not complied with in 2015.

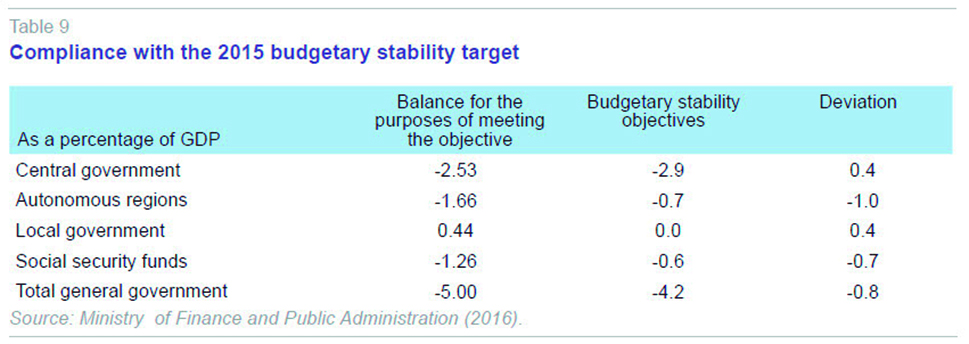

The stability target, which may be for a deficit, equilibrium or a surplus, was set at -4.2% for 2015 for the general government as a whole. After discounting financial support to credit institutions (853 million euros) and costs incurred as a result of the Lorca earthquake (39 million euros), it came to 5.0%. The deviation was therefore 0.8% of GDP. This deviation is distributed across the four subsectors in the European System of National and Regional Accounts, as shown in Table 9.

The autonomous regions and social security system emerge as the cause of the deviation. However, the degree of compliance by the various agents needs to be qualified for two reasons. Firstly, the targets are set by the central government and the national parliament, such that there is a big imbalance between each agent’s autonomy of income and volume of spending. Experience shows that although formally the targets have to be approved by the fiscal policy coordination body (the Fiscal and Financial Policy Council), in which the autonomous regions are represented, the target set is much easier for the central government to reach than for the autonomous regions.

Secondly, the income and expenses of the various agents are interrelated. To mention just two significant examples: the balance of the social security fund depends on a transfer to SEPE by the central government. In 2015, this was 0.9% of GDP, which was 0.3 points lower than in 2014. Another relevant example is that the autonomous regions’ main source of income is their share of income tax collection. This is distributed in the form of advances, which represent a reduction in the central government revenues.

[6] Thus, increased regional income means reduced central government income. Consequently, any noncompliance of the budgetary stability target is at the overall level, and cannot be attributed just to an isolated subsector.

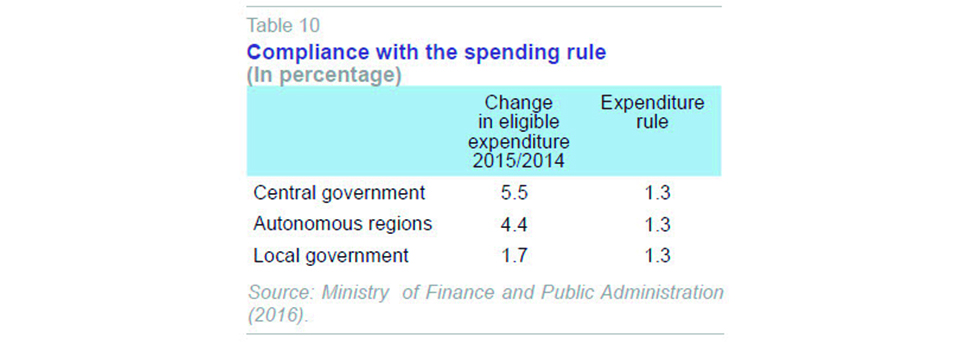

As regards the expenditure rule, the reference rate for medium term gross domestic product growth, calculated for 2015 by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Competitiveness on the basis of the European Commission’s methodology, was set at 1.3%. The relevant spending by the central government, the autonomous regions, and local authorities ought to have been kept within this limit. Table 10 shows that the target was not complied with across the board.

The central government did not comply with the expenditure rule due to the impact of tax reform on the valuation of eligible expenditure, as it meant a permanent reduction in tax revenue of 5,225 million euros. It is also worth remembering that the central government alone met the stability target, illustrating the redundancy between the two targets, the spending target being more demanding.

In the case of the autonomous regions, noncompliance was due to the increased spending on hepatitis C treatment and the recording of investments made in previous years through public-private partnerships. If these two items are discounted, the regions’ eligible expenditure would have grown by 2.2%. Moreover, almost all the autonomous regions failed to comply with the spending rule, the only exceptions being the Canary Islands, Galicia and the Basque Country (which also met the stability target).

Finally, the debt target had been set at 101.7% of GDP and has therefore been met in aggregate terms. By levels of administration, only the autonomous regions overshot the target at the end of 2015, with a debt of 24.2% compared with 24%, after various adjustments were made raising it from the initial 21.5%.

LOEPSF is the fiscal rule governing internal stability, but Spain is also subject to the European Union’s Stability and Growth Pact. In April 2009, the Council of the EU started Excessive Deficit Procedure under Art. 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). In June 2013 the deadline for correcting the excessive deficit was extended to 2016, in view of the fact that despite the corrective measures adopted, the adverse developments in the economy had made it impossible to comply with the original timetable. The new deadline meant correcting Spain’s deficit to bring it to 4.2% in 2015, which as mentioned above, was not achieved.

In October 2015, the Commission gave an opinion on the draft budget plan for 2016 and warned that there was a risk of falling short of the forecasts in the Stability and Growth Pact, due to the budgetary impact of increased spending and the income tax reform. Later, the Commission Recommendation of March 9

th, 2016, said that “Spain should take measures to ensure a timely and durable correction of the excessive deficit, including by making full use as appropriate of the preventive and corrective tools set out in Spain’s Stability Law to control for slippages at the subcentral government level from the respective deficit, debt and expenditure rule targets.”

[7]

It is therefore clear that neither Europe’s nor Spain’s fiscal rules have been complied with. Following the Commission’s recommendation, sanctions of up to 0.2% of GDP may be imposed under TFEU. Spain is in a delicate position because, unlike other previous episodes of noncompliance, it is clear in this case that the overshoot was caused by expansionary fiscal policy, which was pursued contrary to the European Commission’s expectations. A series of budgetary measures were taken in 2015 that reduced revenues while increasing expenditure. This policy was a result of the electoral cycle affecting three levels of government (except in the Basque Country and Galicia, which hold elections in 2016), but this did not preclude the structural deficit rising from 1.9% of 2014 to 2.9% in 2015.

The consequences of imposing this penalty are difficult to predict. In any event, the fact that it is necessary to impose a penalty on a Member State illustrates that the “preventive arm” of the Stability and Growth Pact has been ineffective and its institutional design needs to be rethought.

[8]

Outlook for 2016 and 2017

The state of the public accounts needs to be corrected without delay. However, for the time being, the European Central Bank’s monetary policy and other favourable factors make the situation less urgent than in the 2010 and 2012 debt crises. The level reached by public debt, and the fact that there is still a primary deficit and negative savings rate, makes public services and social-security benefits vulnerable to future international financial market tensions.

The macroeconomic forecasts for Spain produced by the government, in its 2016-2019 Stability Programme Update, the European Commission in its recent spring report, and private analysts are all positive. The government forecasts GDP growth of 2.7% in real terms for 2016 and 2.4% in 2017.

[9] On the hypothesis that no new legislative measures will be adopted, both the Independent Fiscal Responsibility Authority and Laborda and Fernández (2016) estimate that the economic cycle will reduce the deficit to 4% of GDP in 2016 (see AIReF, 2016a). Spain has proposed a new course towards correcting the deficit to the European Commission, which would situate it at 3.6% in 2016 and 2.9% in 2017. To this end it has adopted budgetary non-availability agreements for both the central government and most autonomous regions, set at 0.4% of GDP. Nevertheless, the European Commission, in its Council Recommendation on May 18

th, 2016, highlighted that Spain should adopt permanent measures and establish a deficit target for 2016 of 3.7% of GDP and for 2017 of 2.5% of GDP.

[10]

Beyond the short-term measures being adopted, Spain needs to consider long-term reforms. These cannot be put off any longer given the risks the public accounts face. First of all, reforms are needed to boost the productivity of the economy. Some of these affect revenues and public expenditure, in particular their composition. For example, those concerning the education system, R&D, public-private financing of infrastructure (and its evaluation), administrative reform, etc. There is also an urgent need to address structural problems in the budgetary stability policy and financial sustainability of the public sector. As described by the figures above, the central issues at the moment are the low level of fiscal pressure, the pension system and social security deficits, and coordination of budgetary stability policies with the autonomous regions.

As regards resources, in the 2016-19 Stability Programme Update (SPU) the Spanish government projected that public revenues would rise above their current level of 38.2% of GDP only slightly, to 38.5%, in 2019. This is despite the fact that, as Table 1 shows, the level of fiscal pressure in Spain is more than 8 percentage points below the euro area average. This projection appears to be inconsistent with the growth forecast for the reference period, as AIReF (2016b) says: “proceeding towards the 2019 forecast horizon certain risks are increasingly apparent associated with inconsistencies between the macroeconomic context and the fiscal projections.” This translates into an upside risk “in the public revenue forecast. Given the strong cyclical recovery of productive activity and the labour market, the effect on tax revenues envisaged in the SPU may be considered conservative.” From this it may be deduced that if revenues grow in accordance with the expected economic cycle, new legislative measures will be taken to cut taxes in order to maintain the level of fiscal pressure approximately constant. This is a legitimate option, but it places the burden of correcting the budgetary imbalance entirely on the public expenditure side. In the government’s view, the tax reforms that came into force in 2015 and 2016 “were entirely neutral in terms of the public sector deficit. Moreover, in macroeconomic terms, there is increased dynamism in the tax base in 2015 relative to 2014 due to the implementation of the income tax reform.”

[11]

However, perhaps Spain needs a thorough reform that broadens the tax base, reduces fraud and evasion, and sets fiscal pressure in line with the level wanted by society. Keeping public revenues at 38.5% of GDP does not seem to be compatible with Spanish society’s demand for more and better public services. In any event, this is a political decision that has to be based on an adequate social consensus.

As regards the sustainability of the social security system, as we have seen, the growing deficit is explained by trends in social security contributions, which are insufficient to meet the increase in costs arising out of new pensions and annual updates (at least 0.25%). According to the Independent Fiscal Responsibility Authority, the deficit observed in 2015 will persist in 2016, because “employment, trends in workers’ remuneration, and the increased social security contribution basis make it possible to explain an increase in contributions of around 3% in 2016.” Revenues from contributions will continue to suffer from the effect of the contribution cuts adopted (flat rate, 500 euro exemption, etc.) and the decrease in interest from the Reserve Fund. The State Budget for 2016 includes a merely declarative provision, opening up the possibility of broadening the social security benefits considered non-contributory. This would allow the State’s contribution to social security revenues to be increased in the future.

[12] More funding from general taxation would probably enable the social security system to return to equilibrium, while recent reforms restricting access and the size of benefits will have longer-term effects. In this regard, the European Commission (2015) estimates that pension spending will be 11.8% of GDP in 2020 (the same as in 2013), and 11% in 2060. This all assumes that current legislation remains unchanged and that the hypotheses regarding economic growth, labour market participation, etc. are fulfilled. Although this projection is reassuring, it should be noted that it implies a reduction in the ratio of average public pensions to average wages of 19.9% in 2060. This casts into doubt the political feasibility of the estimates’ underlying assumption that there will be no legislative changes.

In the case of the autonomous regions, since 2012, the regional deficit seems to have stabilised between 1.6% and 1.9% of GDP. This suggests that the margin for fresh cuts may have been exhausted and that the time has come for serious reforms. The core problem is that current expenditure exceeds current income, which is not sustainable over the medium term. A set of measures based on three pillars is needed to correct this situation. First of all, it is necessary to broaden the autonomous regions’ own fiscal leeway by enabling them to raise more revenue themselves. This may require a reform of the current financing system in the common system. Secondly, the budgetary stability rules need to be reformed so that the deficit objectives are more realistic and corrective measures – or penalties, where applicable – are applied automatically to regions that do not meet their targets. This also means that the stability targets have to be different for each region, as AIReF has recommended.

And finally, it will be necessary to return the regions to the discipline of the markets. To do so it will be necessary to put an end, within a reasonable timescale, to the cost-free and almost unlimited finance from the regional liquidity fund(FLA in its Spanish initials) and other State funding mechanisms. This will help ensure that future debt is solely intended to finance investments, provided long-term ability to pay.

In short, the overall assessment of Spain’s public accounts in 2015 is that the process of fiscal consolidation begun in 2010 was deliberately interrupted. The change in direction was a result of the electoral cycle and will hopefully be corrected as of 2016. However, Spain’s experience reveals the failure of the current fiscal rules. European legislation should be simpler and more credible. This means applying the expenditure rule, coupled with control on the level of public debt.

[13] A reform of Europe’s fiscal rules is not incompatible with improvements to Spain’s Budgetary Stability and Financial Sustainability Law, in particular as regards its practical application.

Notes

The deficit was 5%, against a target of 4.2%, excluding (in both cases) the net balance of assistance for financial institutions.

We refer to the Spanish government’s proposal pending approval by the EU at the time this article was written.

Public investment in the euro area reached 4.3% of GDP in 2014, compared with 3.6% in 2015.

The data in Table 4 also include the Wage Guarantee Fund, which is not discussed here as it is relatively small. The differences between the national accounts and the budgetary figures are small in this case.

Organic Law 2/2012 of April 27th, 2012, on Budgetary Stability and Financial Sustainability (LOEPSF).

This refers to the autonomous regions in the so-called common system, i.e., excluding the Basque Country and Navarre.

For a critical assessment of the current Stability and Growth Pact see, for example, Clays, Darvas and Leandro (2016).

The European Commission’s estimates are very similar, at 2.6% in 2016 and 2.5% in 2017. See European Commission (2016). Private analysts, such as Laborda and Fernández (2016), give the same figure for 2016 (2.7%) but are slightly more pessimistic about 2017 (2.3%).

The eightieth additional provision states that: “The government will advance on ensuring the compatibility of the budgetary stability and financial sustainability objectives with the full funding of universal non-contributory benefits from the general government budget, and to do so shall evaluate the conditions of the benefits included in the system that may be considered to belong to this category.”

This is a proposal made by Clays, Darvas and Leandro (2016).

References

AIReF (2016a),

Informe sobre los Presupuestos iniciales de las Administraciones Públicas para 2016 [Report on the initial Government Budget for 2016], http://www.airef.es/system/assets/archives/000/001/407/original/ 2016_04_06__Informe_Presupuestos_Iniciales_2016_ULT.pdf?1459945107— (2016b),

Evaluación del Proyecto de Actualización del Programa de Estabilidad del Reino de España 2016-2019 [Evaluation of the draft update to the Kingdom of Spain’s Stability Programme], http://www.airef.es/system/assets/archives/000/001/449/original/ 2016_04_26_Informe_Evaluaci%C3%B3n_del_Proyecto_de_Actualizaci%C3%B3n _del_Programa_de_Estabilidad_del_Reino_de_Espa%C3%B1a_APE_%C3%BAltimo.pdf?1461660189CLAYS, G.; DARVAS, Z., and A. LEANDRO (2016),

A proposal to revive the European Fiscal Framework, Bruegel Policy Contribution 2016/07,

http://bruegel.org/2016/03/a-proposal-to-revive-the-european-fiscal-framework/COM (2016) 329 final:

http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/pdf/csr2016/csr2016_spain_en.pdfEUROPEAN COMMISSION (2015), “The 2015 Ageing Report,”

European Economy, 3|2015,

http://europa.eu/epc/pdf/ageing_report_2015_en.pdf— (2016), “European Economic Forecast. Spring 2016,”

European Economy, Institutional papers 025, May 2016,

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/eeip/pdf/ip025_en.pdfIMF (2016),

Fiscal Monitor: Acting now, acting together, April 2016,

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fm/2016/01/pdf/fm1601.pdfLABORDA, A., and M. J. FERNÁNDEZ (2016), “Ralentización económica en un entorno de incertidumbre,”

Cuadernos de Información Económica, nº 251: 1-16,

http://www.funcas.es/Publicaciones/Detalle.aspx?IdArt=22303MAUDOS, J. (2014), “Sostenibilidad de la deuda pública: España en el contexto europeo,”

Cuadernos de Información Económica, nº 239: 65-75,

http://www.funcas.es/Publicaciones/Detalle.aspx?IdArt=21322MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION (2016), “Informe sobre el grado de cumplimiento del objetivo de estabilidad presupuestaria, de deuda pública y de la regla de gasto del ejercicio 2015,” [Report on compliance with the budgetary stability, public debt, and expenditure rule objective in 2015],

http://www.minhap.gob.es/Documentacion/Publico/CDI/ Estabilidad%20Presupuestaria/Informe%20Completo%20EP%202015%20(1).pdf

Alain Cuenca. University of Zaragoza