Regulatory shocks and a weak operating climate: A toxic cocktail for banks

New regulatory changes affecting resolution regimes and imposing limits on payment of dividends/coupons on financial instruments are increasing pressure on European banks already facing a difficult operating climate. This negative impact, however, is likely more a consequence of regulatory uncertainty rather than the new measures themselves.

Abstract: Regulation serves an important function within the financial system, ensuring financial stability and consumer protection. However, while the current crisis has brought to light the need for regulatory changes, concerns about implementation of recent measures are adding uncertainty to an already challenging operating climate for European banks. In fact, the underperformance of European banks relative to other sectors unquestionably reflects perceptions that the banking business is far more exposed than other sectors to economic weakness and ulta-low interest rates. However, European bank shares have also been affected by new regulations, which substantially change the rules of the game as regards resolution regimes, as well as limits on maximum distributable amounts (MDAs) applied to financial instruments. The former change has had the most significant impact in the case of Italy, while the latter in the case of Germany.

The start of the year has been particularly harsh on European banks in terms of share price performance and the value of other listed financial securities, particularly those whose holders may now have to absorb losses in the event of resolution.

This value destruction is attributable to a dangerous combination of an extremely weak operating environment –zero growth and zero or even negative rates– and the effectiveness of certain new regulatory measures, which radically change the way losses are absorbed in the event of bank resolution, as well as imposing serious limits on the payment of dividends and/or coupons on the financial instruments issued by banks.

In our view, it is not so much the advent of the new regulatory framework, but rather the uncertainty lingering as to its effective application which the market has penalised, all of which against a macroeconomic backdrop hardly favourable to the banking business.

Financial sector regulation: Raison d’etre and responses to the crisis

Regulation is an intrinsic part of the banking business and has important implications for banks’ risks and returns. In turn, these regulations form part of the social contract between the banking system and society: the financial institutions act as intermediaries in the financial system, a function performed in a regulated environment, which has two basic objectives (see Afi, 2015):

- Ensure the stability of the financial system as a whole, which essentially entails defending it against distress, external or internal, which could have an adverse impact on this stability, ensuring the various markets work as intended and overseeing that the system players are adequately capitalised and have suitable risk controls;

- Protect financial service users, particularly those in greatest need of protection: retail customers, who generally lack the required financial acumen or resources to operate in this arena without sufficient guarantees.

Although the need for financial stability has always been present, the current crisis has highlighted the need to ensure the stability of the system per se rather than the financial health of individual institutions, historically the object of financial regulations and supervision.

This reality is behind what is known as systemic risk, which can be defined as in Regulation (EU) No. 1092/2010, of November 24th, 2010, on European Union macro-prudential oversight of the financial system and establishing a European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB): “a risk of disruption in the financial system with the potential to have serious negative consequences for the internal market and the real economy”.

Having identified this risk, the purpose of macro-prudential oversight is to prevent or mitigate systemic risks to financial stability arising from developments within the financial system and taking into account macroeconomic developments so as to avoid periods of widespread financial distress.

We have sought to emphasise this oversight function not just because it is new but above all because it has yet to be implemented in Spain, which presently does not have a well-defined macro-prudential authority (additional provision 18 of Spanish Law 10/2014), notwithstanding the temporary assignment of some of these competencies to the Bank of Spain (transitional provision 1 of Spanish Royal Decree 84/2015) and performance of the macro-prudential functions vested in the ECB with respect to significant entities.

The consumer protection impetus is in the system’s own interests as consumers would not put their money in it if they did not feel duly protected by the system’s regulations.

The prevailing crisis has prompted a raft of regulatory initiatives designed to enhance consumer protection in response to the cases coming to light in some countries, including Spain. These initiatives have been mainly articulated around two lines of action: mortgage holder protection and malpractice in the distribution of certain financial instruments.

At any rate, the consumer protection thrust goes beyond regulation insofar as the banks have suffered reputational damage which has required them to approach their customers in a more proactive manner.

Elsewhere, the current crisis has spawned the creation of new institutions, not previously contemplated, which have naturally needed their own rules and regulations, just as these institutions contribute to the development of new regulations in the course of exercising their functions.

In this paper we do not attempt to specifically address all of these new regulations, but it is worth highlighting the fact that they affect:

- The aforementioned ESRB and the three European Supervisory Authorities (EBA, EIOPA and ESMA, together the ESAs).

- Banking union, which so far has two pillars (while the creation of a potential European deposit fund is pending):

- The Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), tasked to the ECB, which has already given rise to very comprehensive and specific implementing regulations, which is not to say that these will not continue to be fine-tuned in accordance with this body’s experience and needs.

- The Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM), underpinned by the Single Resolution Board and the Single Resolution Fund, which has still to be implemented.

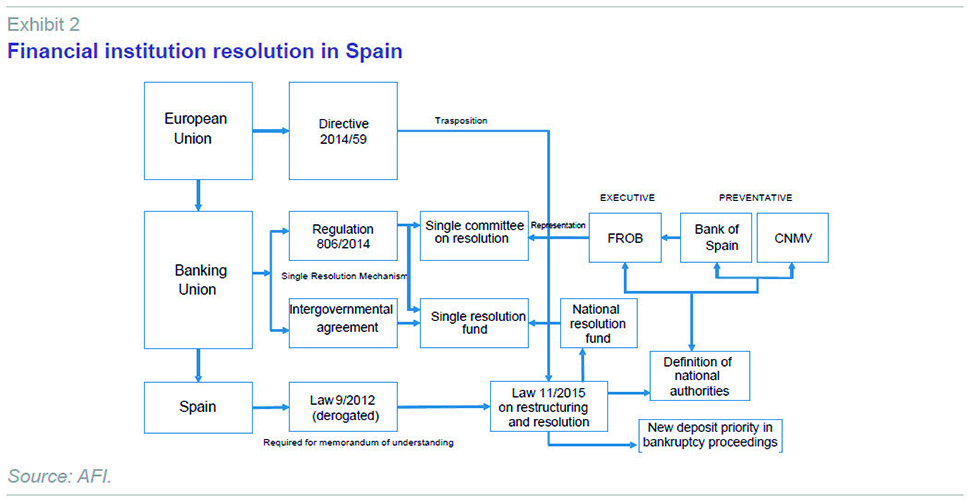

Because resolution of the various banking crises was not homogeneous across the EU, other than involving public aid across the board, the EU has published Directive 2014/59/EU, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), which has introduced a substantial shift in the apportionment of the costs of a crisis towards the investment community (bail-in) and away from the public sector (bail-out, the former modus operandi), the consequences of which have yet to be truly tested on a crisis at a real systemic entity, although Spain has had some experience as a result of the Memorandum of Understanding signed with the rest of the eurozone nations in exchange for the provision of funds for resolving its banking system crisis.

Meanwhile, the resolution solution being cobbled together for a group of Italian financial institutions, which goes in a different direction, highlights the difficulties of putting such as radical change into practice, raising the costs borne by the banks’ shareholders and investors, making it harder for these institutions to secure financing.

We should also mention the fact that because one of the issues detected during the crisis was uneven application of EU regulations by its member states, the new regulations have largely taken the form of binding and directly applicable regulations rather than the traditional directives, although these have not disappeared altogether.

However, a regulation can leave some of its elements to development by the member states or their authorities (the so-called national options), which has given rise to intervention by the ECB, as the competent authority for the SSM in respect of significant supervised entities, in an attempt to regulate as many options and discretions as it has been able to, thereby increasing regulation in this arena.

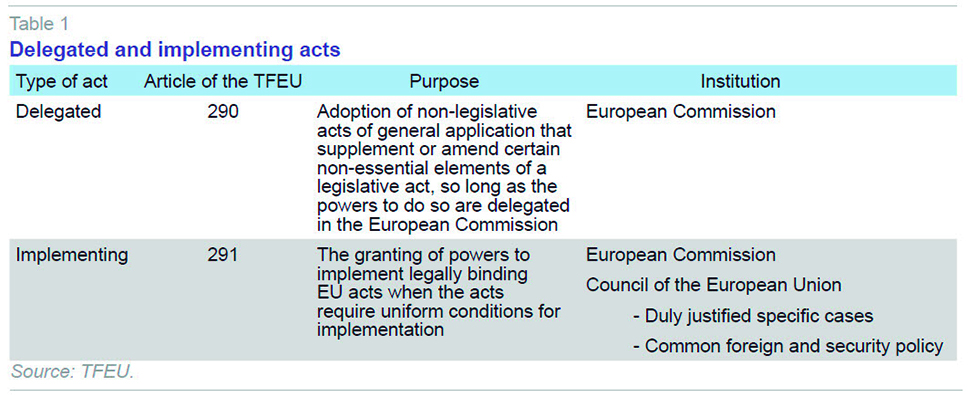

[1]

Regulatory processes: Complexity and uncertainty

These reflections, and those that could be posited regarding the quantity and quality of the regulations, cannot be separated from the procedures used to approve the regulations and the context in which they are amended.

The current crisis has necessitated, and continues to require, many regulatory modifications of varying scope which, in general, imply very substantial changes with respect to the pre-existing situation, not only on account of the depth of the changes made to the previous regulations but also because they now address new or formerly scantly addressed aspects, such as remuneration and liquidity risk, to cite a couple of examples.

Irrespective of how well they may be drafted, for example in terms of internal consistency, the effectiveness of the new regulations must be tested and borne out in reality, which is precisely why they often have to be modified, sooner or later, if, ultimately, they do not work as anticipated or are not capable of tackling the new problems adequately.

This does not mean that all draft regulations should not be subjected to as much prior quality testing as possible. To the contrary. We are referring, for example, to testing in the sense of:

- Being accompanied by impact analyses designed to estimate their effects on the affected entities and, very importantly, for the real economy. These studies will inevitably be based on assumptions which, as such, do not always correspond with reality.

- Being subjected to consultation for a reasonable period of time during which the affected entities, either directly, or through the associations which represent them, can channel the observations they deem opportune. This feedback should be evaluated by the regulators before approving the new regulations.

- Being put through the controls contemplated in the regulations themselves, such as, in the case of the EU, the subsidiarity control mechanism for participation by national parliaments. [2]

The European Commission (EC) operates a Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme (REFIT), [3] which was rounded out in the middle of April 2016 with an Interinstitutional Agreement on Better Law-making [4] among the EU’s three main institutions responsible for the bulk of its front-line regulations: the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission.

- Anticipating the required implementing regulations and the opportune delegations of powers to the European Commission and, if warranted, the

prior work which needs to be performed by the European Supervisory Authorities (ESA) [5] via the corresponding regulatory or implementing technical standards. The former give rise to delegated acts, the latter to implementing acts.

This last idea is based on the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU), reformed by the Lisbon Treaty, as reflected in Table 1, which currently takes the approach proposed by Lamfalussy,

[6] initially tested in securities markets and since applied to all financial services areas.

At any rate, it is an approach which considerably increases the number of EU standards in a given field; recall, however, that these acts have a different legal status. At present, there is a profusion of implementing acts under CRR/CRD IV, which does not mean that the implementation process is complete; indeed, the regulatory effort is barely underway with the attempt to address banking crisis resolution and we can expect to see more standards of this nature in the immediate future.

One peculiarity of the delegated acts is the fact that they generally see the light of day months after they are approved by the European Commission, regardless of whether their origin lies with the Commission or one of the ESA’s technical standards. The fact is that they have to be validated by two co-legislators within a deadline and without this validation they cannot be published. This can generate a sometimes-significant delay in their application.

Moreover, we must not forget that most of the new regulations implemented in Europe are in theory being coordinated at the global level by the G-20, with the Financial Stability Board and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision being the institutions tasked with their implementation, despite the fact that neither institution has been expressly empowered to adopt legally binding acts. This situation certainly gives European regulatory developments greater legitimacy internationally, but does not necessary guarantee their appropriateness or consistency.

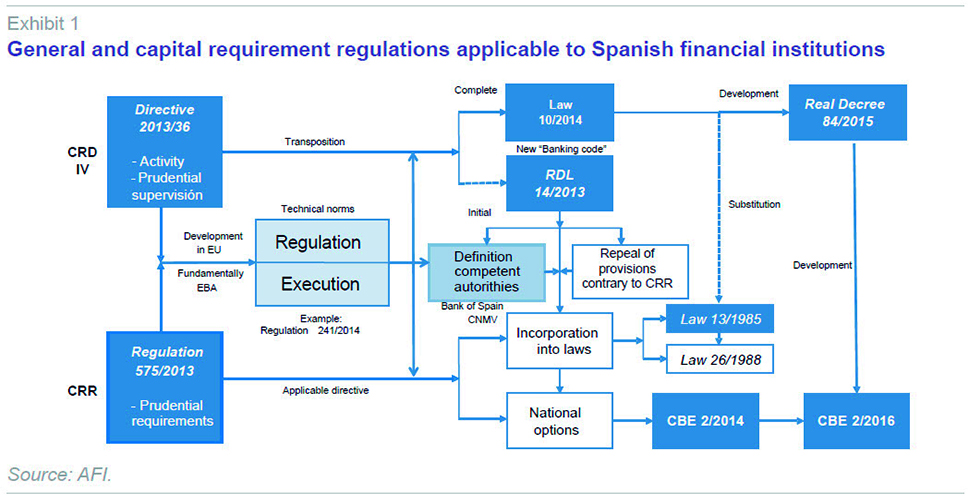

Turning back to the EU, there is, generally speaking, a double level of regulations: the European level and that corresponding to the member states, giving rise to a duality of standards which it is very important to consider in order to understand their scope and interrelationships, to which end the Exhibits included in this paper on banking regulation in general and capital requirement standards in particular (Exhibits 1) and on the resolution of bank crises (Exhibits 2) might be of use.

This regulatory zeal is not likely to conclude in the near term, or even after the transition periods contemplated conclude; for example, there are still some Basel III matters to determine, such as the leverage and medium-term ratios. Without mentioning the unfolding need to address previously unforeseen developments, such as the appropriate treatment of sovereign risk exposure, of great interest to the eurozone members, particularly Spain.

What is clear is that any new regulatory reforms, including the scope for dismantling or rolling back some of the changes already made, must factor in experience and analysis of the changes required.

Regulatory uncertainty in the current banking business environment

In light of the foregoing considerations, it would appear that we have not seen the end of the new regulations designed to mitigate the effects of the crisis and, insofar as possible, prevent a recurrence in the future. Although much progress has been made in recent years, there are still important matters to implement; in parallel, some of the new standards have yet to be tested in reality, a process which could fuel additional regulatory developments for a time.

All of this combines to imply significant uncertainty regarding the outlook on the regulatory front, particularly with respect to certain implementing regulations which lend themselves to different interpretations in respect of certain key aspects, as we will analyse in this section. This uncertainty is not good for bank valuations, much less their ability to attract capital, especially in such a challenging business climate, as the banks contemplate stagnation with rates at or even below zero.

Interest rates of zero per cent, not to mention in negative territory, are extremely harmful for the banking business to the extent that the downward repricing of the interest collected on loans cannot be fully passed through to the remuneration paid for liabilities, particularly those comprised of household and corporate deposits, putting tremendous pressure on net interest margins.

This vulnerability –which affects not only the banks but also the insurance companies– to negative rates has been the subject of debate in the ECB’s press conferences in recent months each time it has cut its benchmark rates further. The standard response provided by the ECB’s president to appeals regarding this vulnerability has been, firstly, that the central bank’s mandate does not include propping up bank margins and, secondly, that the vulnerability is not generalised, that it varies from one country to the next depending on the business model and the relative sensitivity of assets and liabilities to zero or negative rates.

The International Monetary Fund has, however, addressed this source of vulnerability directly. In its

Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR,

http://www.imf.org/External/Pubs/FT/GFSR/2016/01/pdf/text.pdf) it performs a simulation exercise to determine which banking systems are more exposed to the negative rate scenario and to what extent they have room to offset the squeeze on margins by increasing lending.

Vulnerability is higher the more sensitive asset returns are to benchmark rates and the less sensitive the cost of funding to these same rates. Unfortunately, the Spanish banking system is among the most vulnerable on both fronts as it carries a significant percentage of assets (mainly mortgages) whose interest is linked to benchmark rates and a high percentage of household and corporate deposits for which it is extraordinarily difficult to cross the zero-rate barrier.

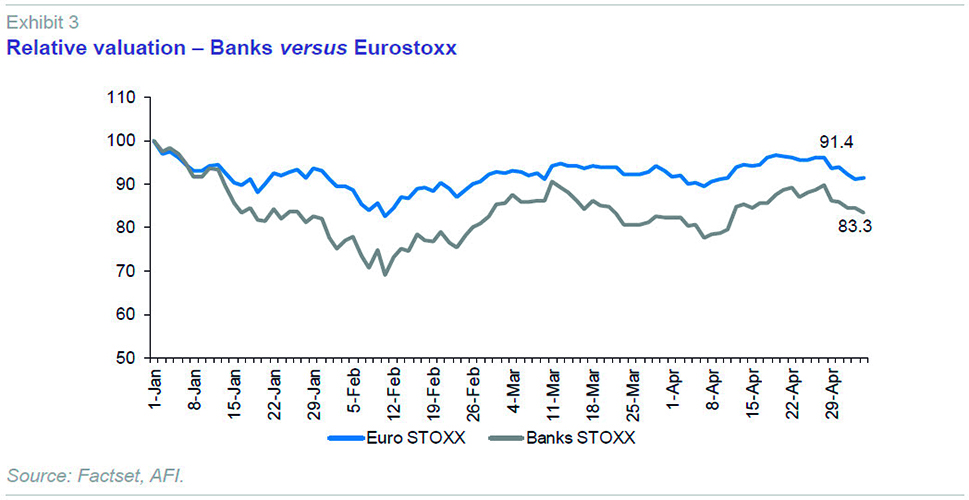

An analysis of the European banks’ stock market performance relative to other sectors evidences the fact that the market has taken stock of the extraordinarily challenging business environment facing banks across Europe, more acutely during the early part of this year. The accompanying exhibit illustrates how European banks (those included in the Eurostoxx) have seen 17% wiped off their market cap so far in 2016, which is more than twice the correction in the overall index (9%).

This underperformance by the European banks relative to other sectors unquestionably reflects the perception that the banking business is far more exposed than other sectors to economic weakness and ultra-low interest rates (which are in fact likely to benefit other sectors).

Within this generally adverse banking business environment, our interest lies with inferring whether the banks’ share prices have also been hurt by changes in banking regulations and the resulting uncertainty. To do so, we have opted to differentiate between countries, emphasising those that have experienced –or continue to experience– the greatest regulatory blows and/or associated implementation uncertainty, essentially Italy and Germany, as we explain further on.

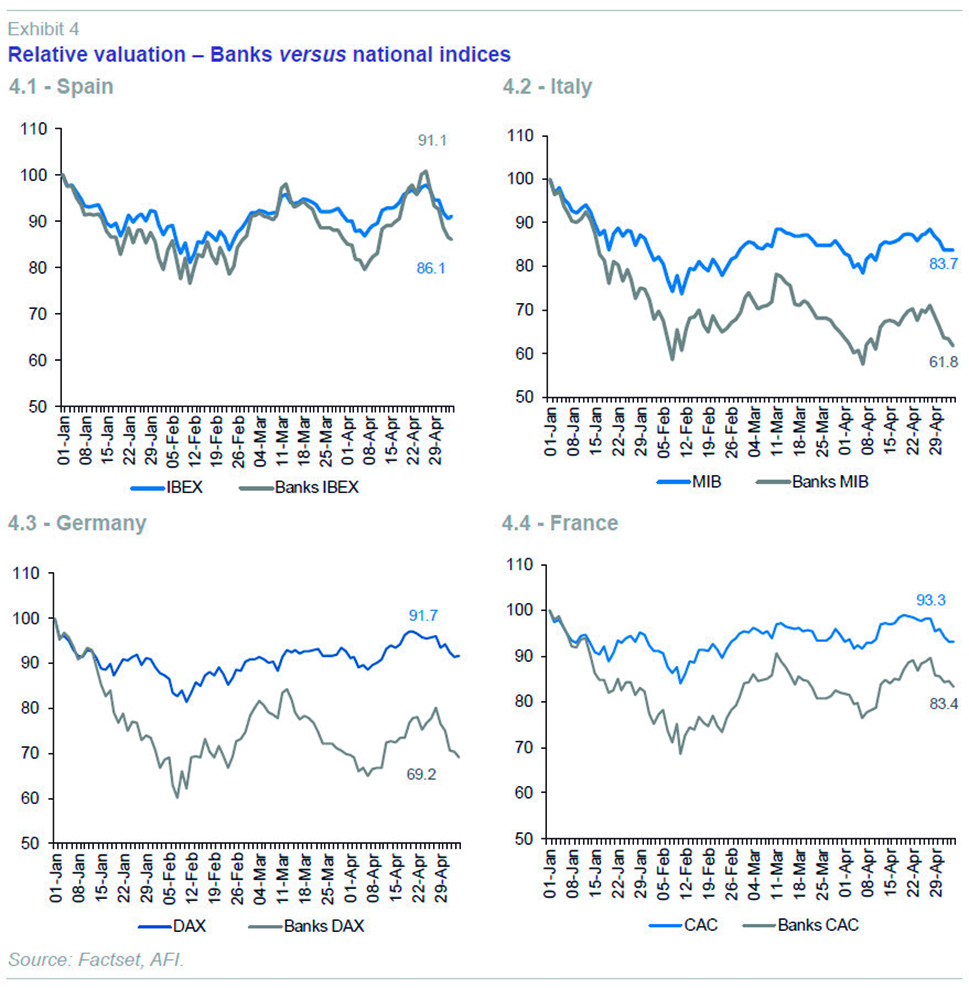

The accompanying exhibits illustrate the stock market performance by the banks relative to the respective general indices in the four major eurozone economies,

i.e., Germany, France, Italy and Spain. Note, firstly, that the banks have underperformed the general indices across the board. In fact, the general indices have performed very similarly in Germany, France and Spain (correcting by 7% to 9%), correcting by a more substantial 16% in Italy.

The banks’ share price performances can, however, be grouped into two clearly different categories; in our opinion, this divergence has a lot to do with regulatory developments and uncertainty.

The Spanish banks’ valuations have held up the best, relatively speaking, correcting 14%, followed very closely by their French counterparts, which have seen their market caps correct by 17%. Paradoxically, although the Spanish banking system is the most exposed to the zero/negative rate environment, as noted above when analysing the IMF’s report, it has performed the best on the stock market on a relative basis. One possible explanation for this paradox is the fact that the Spanish banking system is the system which has made the biggest provisioning effort since the start of the crisis, which probably leaves it currently less exposed to regulatory developments which impose additional capitalisation measures and/or sources of uncertainty with respect to burden-sharing by shareholders and investors in general in the event of resolution.

Leaving the French case aside (whose relative performance is similar to that of Spain), it is worth highlighting the sharp share price corrections sustained by the German and Italian banks, which have seen 31% and 38%, respectively, wiped off their valuations year-to-date. In our opinion, the fact that these two countries’ banks have underperformed their French and Spanish counterparts is closely correlated to the impact of several regulatory changes which have had a particularly significant impact on the banks in Italy and Germany, changes which moreover are associated with considerable uncertainty with respect to their effective implementation and, by extension, their ultimate impact on the affected banks.

A series of new regulations took effect in early 2016 which radically change the rules of the game in terms of the risk borne by holders of various financial instruments issued by banks.

The change in the rules of the game is underpinned by two basic principles. Firstly, the idea that the cost of future bank crises needs to be shared by various classes of investors in troubled banks rather than by taxpayers, as was the case in the recent crisis. In a nutshell, a shift away from a bail-out to a bail-in regime when resolving failing banks.

Coupled with this, and framed by the basic principle of macro-prudential regulation analysed above, the imposition of limits on the amounts which can be distributed by credit institutions (the maximum distributable amounts or MDAs), specifically restrictions on the payment of dividends on shares or coupons on contingent convertible capital instruments (the so-called CoCos, which have recently emerged as the main instrument being used to reinforce capital within the Additional Tier 1 category).

The start of the year has brought to light two cases which clearly illustrate the problems which such radical changes, particularly when associated with uncertainty in terms of implementation, can bring: Italy and Germany are, respectively, examples of the collateral effects of the first and second of the above-mentioned principles (bail-in regime and MDAs).

In the case of Italy, the market woke up to the fact that its financial system faces steep provisioning requirements (non-performing loans stand at 350 billion euros, compared to 130 billion euros in Spain, the two banking systems being of similar size) just as the new bank resolution regulations took effect in Europe (on January 1st). Under the new regime, any sort of public support for Italy’s provisioning effort (either via recapitalisation or the provision of guarantees as part of the creation of a ‘bad bank’ for the transfer of toxic assets) will first necessitate a full bail-in process in which the affected banks’ investors (its shareholders first, its convertible bondholders next and, eventually, even its senior debt holders) would incur substantial losses.

Against this backdrop, the Italian government’s efforts to enact the state aid procedure have entailed an unusual loss-sharing scheme: the good banks will have to come to the aid of the bad banks by investing in securitisation vehicles which repackage bad loans in order to recapitalise the latter. Either way, the losses incurred by the holders of the banks’ securities would not be limited to the failing banks but be borne by the system as a whole: the shareholders of the ‘good banks’ will indirectly share the losses of the bad banks in order to prevent a massive bail-in which would affect the holders of the senior securities (bonds and even maybe deposits) of the most troubled institutions. In our view, that risk of generalised losses across the Italian banking system’s shareholder base is what is really behind the share price collapse in that market.

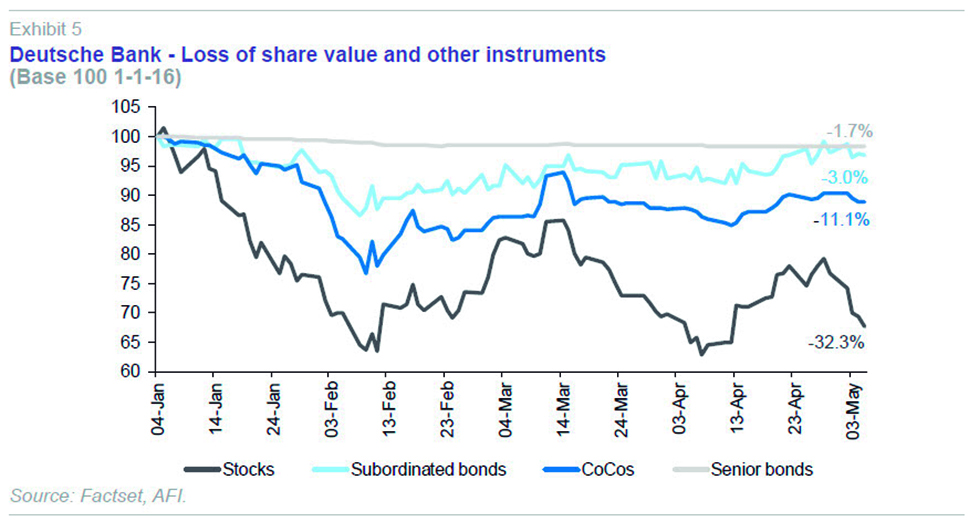

In Germany, meanwhile, the problems related with the new regulations and associated uncertainty are far more concentrated in the country’s largest bank, Deutsche Bank (DB). Under pressure from more stringent capital requirements, particularly in order to meet the leverage ratio (a metric on which this bank has rated consistently below international standards), since the start of the crisis, DB has been one of the most active issuers of contingent convertibles (CoCos, AT1 capital): at year-end 2015, its outstanding balance of these securities stood at almost 5 billion euros. Against this backdrop, in February, DB announced sharp losses (> 5 billion euros) in 2015, shaped mainly by fines and provisions related to unorthodox conduct in the wholesale funding markets (index manipulation, etc.).

Despite the non-recurring nature of those losses, which should not be extrapolated when projecting DB’s business potential, they could hamstring the banks’ ability to pay coupons on its CoCos; this prospect triggered a genuine stampede out of these instruments, driving a correction in their market value and, more importantly, shutting down the market for new issues. In fact, as shown in the accompanying Exhibit, not only did its so-called CoCos sustain losses, the price of all the financial instruments issued by DB corrected.

The fear of widespread contamination to financial instruments (CoCos, subordinated bonds, senior bonds) believed safe until now prompted DB’s management to buy these instruments back in an attempt to curtail this contagion risk. However, that buyback effort ultimately implies transferring a higher bail-in risk to its shareholders, as is evident in the recent relative performance by the various classes of quoted financial instruments. The price recovery in CoCos and subordinated bonds has been offset by a fresh correction in the share price, which is down by over 32% year-to-date. DB’s significant weight in the German bank index, exacerbated by an element of contagion –fear that other German banks could encounter a similar situation–, is responsible for the widespread correction in the German banking sector’s market value. It also provides a telling story of what can happen as a result of exposure to a drastic change in regulations (especially change associated with a significant element of uncertainty in terms of how it will play out) regarding relative ranking when it comes to risk-sharing.

Notes

Protocol No. 2 on application of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality.

These authorities have stakeholder groups (consumers and users, financial institutions, employees, academics, small and medium sized enterprises) for the purpose of fostering their participation in the preparation of these standards.

References

ANALISTAS FINANCIEROS INTERNACIONALES (AFI) (2015), Guide to the Spanish Financial System, 7th edition, overseen by D. MANZANO and F. J. VALERO and sponsored by Funcas.

Angel Berges and Francisco J. Valero. A.F.I. – Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.