Keys elements behind the success of Spanish exports

Following decades of rapid expansion, Spain´s export performance today boasts impressive results relative to many European countries. Despite progress, stable and sustainable economic growth requires Spanish production to continue to become even more export oriented.

Abstract: Spanish exports have outperformed many of their European peers during the latest economic crisis. Recent export growth has received a boost from the past crisis, which accelerated Spanish companies´ expansion to foreign markets to compensate for decreased domestic demand. However, Spain´s solid export performance is largely underpinned by decades of rapid expansion, beginning with Spain’s joining the European Economic Community in 1986, and achieved its greatest successes in the 1990s. Spain´s favourable export performance can be explained by transformational changes of the economy’s productive structure, as well as within its companies, which were forced to respond to increased international competition resulting from globalisation. Spanish companies have now reached high levels of internationalisation, both in terms of exports and FDI, reflecting their highly competitive products, which are increasingly attuned to global demand, and offer quality and differentiation. Despite progress, support measure will be necessary to ensure Spanish production remains focused on foreign markets, and increasing companies’ export intensities, as the recovery in domestic demand stimulates imports, raising the risk of recurrence of trade imbalances.

Introduction

Spain’s worsening economic situation over the course of 2008 and the sharp drop in GDP in 2009 −although slightly less than that in other developed countries− was accompanied by severe job losses and increased concerns over the weakness of Spain´s productive system, something which is frequent in a period of crisis not only in Spain but also abroad.

These concerns had arisen even during the strong economic growth of the preceding years. In particular, the warning signs were the trade deficit with the rest of the world in both goods and services, and the poor progress of labour productivity, which is a fundamental pillar of national economic growth. Both indicators lent support to the hypothesis that the Spanish economy was suffering from serious supply-side issues and problems with the price of its products, hindering growth and competitiveness.

In the midst of the latest crisis, politicians´ and economists´ search for a positive feature in the Spanish economic model led to a focus on export performance, which reflected relatively rapid growth. Sceptical observers attributed such performance to firms looking for markets abroad to compensate for the weakness of domestic demand, i.e., a temporary solution that did not alter the underlying weakness of the productive system.

However, the reality is that from 2009 to 2013, Spain’s economy has been shored up by exports, which even without a devaluation became the motor of the economic recovery in the wake of the crisis. This strong performance of exports is the product of a long and fortunate path Spanish companies have taken to orient themselves towards markets in the rest of the world, in response to economic globalisation.

[1]

Exports during the crisis

After the slump in economic activity in 2009, which affected world trade, given its general scope and greater intensity in developed countries, Spanish exports began to grow rapidly, to the extent that at the end of 2015, they were 22% higher in volume terms than in 2007, the last year of the expansionary phase at the start of the turn of the century. In terms of annual change, the years since 2010 have registered increases of more than 4.5% in volume terms, i.e., discounting the effect of price alterations. This strong increase made a decisive contribution to averting an even bigger collapse in economic activity, sustaining employment levels.

Foreign sales have also grown in comparative terms, exceeding Europe’s leading exporter, Germany, by a few tenths of a point, and exceeding the EU-15 average by a full percentage point. It is no surprise, then, that exports have become the most salient positive feature of the Spanish economy. Or that their performance has made it necessary to take a closer look at the Spanish productive system.

This increase in Spanish exports is also surprising because their main market –Europe– was hit particularly hard by the economic crisis. As a result, the expansion abroad has had to rely more on emerging markets, where Spanish firms have a weaker foothold. This fact, while highlighting Spanish companies’ delay in diversifying their markets, also reveals their notable adaptation to a changing environment. As a result, the differences in activity, efficiency and profitability between companies that export and those that do not has grown over the course of the crisis (Eppinger et al., 2015).

Contrary to the popular belief that Spain’s export capacity rests on tourism, goods exports account for 67% of the total and have performed particularly well, with increases of close to 5% a year over the period 2009-2015. In reality, tourism accounts for around 14% of income from exports of goods and services, and grew moderately over the years of recession, reflecting the difficulties of its main European consumers from Germany, Britain and France. Moreover, exports of non-tourism services, which exceed tourism by volume, have grown faster.

It should not be concluded from this that tourism is irrelevant, however. It is a key industry, in which Spain excels, ranking among the world leaders in terms of earnings and number of tourists, which after a record in 2014, reached new highs in 2015 with the arrival of 68 million people. The industry’s significance lies above all in that its operations always yield a highly positive balance with the rest of the world, which helps finance part of the deficit on the goods trade balance.

The paralysis of the internal market, as households, businesses and the government pay down their debt, has undoubtedly spurred companies to look for new markets abroad. Indeed, some estimates have placed more weight on this factor in the years the recession was deepest, starting in 2009. But the main stimuli came from growth in developing country markets in the period to 2013, when the first signs of deceleration became apparent, and with the drop in value of the euro until 2012. In 2013 and 2014, the European currency appreciated, as a consequence of Germany’s foreign trade surplus – and that of the EU as a whole – and the application of a less expansionary monetary policy in the Euro area than that of the United States or United Kingdom, which were offering lower returns on financial assets. This factor combined with increasing world trade to slow Spanish exports in the summer of 2014. The subsequent depreciation in the euro, together with the falling oil price, encouraged a recovery in the following months, but not as vigorous as desired, as world trade is showing signs of stagnation, having grown at 2.8% in 2015, i.e., less than world GDP. With the exception of 2009, this is something that has not happened for a long time (Jääskelä and Mathews, 2015; Gros, 2016).

One final characteristic is worth noting: growth in Spanish exports in the past few years has not only been driven by the main exporting companies selling more of their products on markets in which they were already operating (what economists term intensive margin), but Spain’s presence abroad has also been expanded with new companies and products, and its companies have penetrated new markets (extensive margin). In particular, although it remains low, the percentage of small and medium-sized enterprises that export has grown steadily. A very large share of companies with over 200 employees already export. According to information from the Foreign Trade Institute (Instituto de Comercio Exterior, ICEX), the number of exporting firms with an export turnover of more than 50,000 euros has grown at rates of more than 3% since 2010. The number of firms exporting regularly has also grown, albeit more slowly.

Meanwhile, there has been a rise in the number of firms in the leading group, including both those with foreign sales in 2014 of over 50 million euros but less than 250 million euros (almost 500 firms), and those with exports of over 250 million euros (101 firms, with Telefónica, Repsol, Inditex, Bayer Hispania, Cepsa, Seat, Abengoa and Corporación Gestamp topping the ranking). Large exporters have strengthened their share of total exports.

A long growth trajectory

Although it may be surprising, the positive trend in exports in recent years forms part of a long-term trend dating back to 1960, when the Spanish economy abandoned the principles of self-sufficiency that had prevailed during the first twenty years after the civil war. This was followed by a period of rapid expansion, taking advantage of the golden age of post-war European growth. However, it was Spain’s joining the European Economic Community that would expose Spanish firms most directly to international competition, forcing them to turn to foreign markets to replace domestic ones.

Indeed, Spain’s industrialisation during the 1960s and 1970s was consolidated in a context of a domestic market that still enjoyed a relatively high degree of protection. The profound crisis in the 1970s, resulting from rising prices of oil and other commodities and the adoption of restrictive fiscal and monetary policies by developed countries to rein in the resulting inflationary tensions, spurred companies to turn increasingly towards foreign markets. Finally, joining the European community forced Spanish firms to undergo a profound transformation, supported by fiscal measures to encourage them to re-equip.

Spain’s membership in the European community in 1986 ultimately meant the dismantling of its protectionist barriers against other member countries. This process was a gradual one, lasting seven years and being completed in 1993. This period also saw the construction of the European single market by eliminating non-tariff barriers restricting competition within the community, removing border posts, which had raised the cost of sending goods abroad, and harmonised health and safety specifications, so they could not be used to disguise domestic market protection. Spanish companies therefore faced a huge process of change, opening up the domestic market to companies from other member countries.

Any process of international competition exposes companies to a more competitive environment in which they face foreign rivals. This incentivices them to raise their levels of efficiency and degree of product specialisation. To do so, they give up producing goods and services at which they were less skilled and efficient, to concentrate on those in which they have a competitive advantage, being more unique than those of their rivals, or for which they can obtain a better price. The outcome of this process is a more open and competitive international market, with a wider variety of goods and lower prices.

This process is normally beneficial for the country concerned, given that, as Adam Smith pointed out, consumers have a wider variety of goods available at lower prices and firms have new business opportunities. The less efficient firms disappear, but the more efficient ones produce at a lower cost and find bigger markets for their products. Focusing on these new markets is a necessary survival strategy, because firms have to share space in their domestic market with firms entering it from abroad and offering new varieties of products. However, at the same time, it is an opportunity to consolidate their products and advance towards new ones, manufactured with the latest technologies, utilising the information received from new consumers and rival companies.

Exhibit 1 shows how Spain’s exports have grown as a share of the EU-15 total, reflecting in simple terms how Spain’s firms have internationalised. This share has risen from below 3% in 1960 to close to 7% today. This figure is not close to Spain’s share of the region’s output, which is slightly more than 10%, but this is a trait shared with France, Italy and the United Kingdom. The reason for this is that Germany is more focused on foreign trade than these other countries, and accounts for a proportionately larger share. This is also true of some smaller countries, whose size means they rely on exports for their producers to achieve economies of scale.

It is worth looking more closely at some of the details of Spain’s trajectory. For example, Spain’s share of exports rose rapidly until the crisis in 1973, receiving a boost from the Preferential Agreement with the European Economic Community that was very favourable to Spain’s interests. The following decade was marked by the pressing need to find alternative foreign markets. This began to moderate in 1985, thanks to the recovery in domestic demand. The 1990s, in which the creation of the European Single Market begun in 1987 was culminated, was a period of rapid expansion in Spanish exports, growing at an average annual rate of 10% in volume (11% in the case of goods). This rise was given a considerable boost by three devaluations of the peseta in the early years, which corrected the overvalued rate at which it joined the European Monetary System (the precursor of the European Monetary Union) in 1989.

In the 2000s, export growth slowed in developed countries, including Spain, although remaining at a healthy 4.3% in volume terms, one percentage point higher than annual GDP growth. However, this strong rate of growth was insufficient for Spain to maintain its share of European community exports, which had been on a steep downward trend since 2003. The current crisis has aided its recovery, with export growth ending 2015 at 6.5%, close to the peak it reached in 2003 (6.9%). The main reason for Spain’s loss of market share in EU exports between 2003 and 2008 is not the country’s higher labour costs, as the Bank of Spain

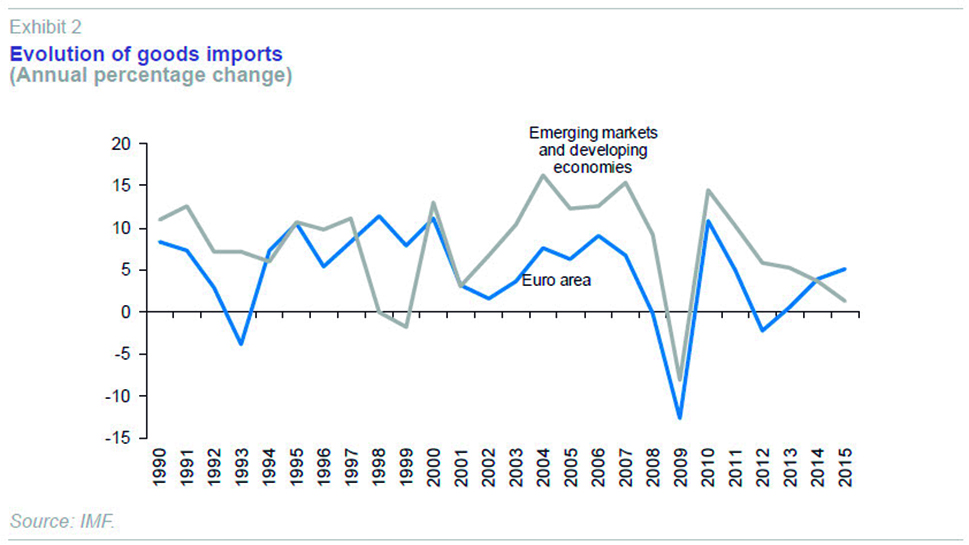

[2] has often argued, or the rapid growth of domestic demand. It has rather been the concentration of Spain’s exports to EU countries, whose imports slowed during the period, in contrast to the situation in emerging countries (Exhibit 2). Countries better positioned in Asia than Spain, such as Germany in particular, managed to increase their exports considerably. Although Spanish companies were increasingly targeting these new emerging markets, they were unable to take advantage of their potential for expansion in the period concerned, although they have done so since 2010.

The big transformation in the 1990s

The 1990s undoubtedly deserve particular attention in view of the rates of export growth achieved. This is the period in which everything that began the previous period, following Spain’s joining the European community, seems to have come to fruition, and was the prelude to the final mature phase in the 2000s.

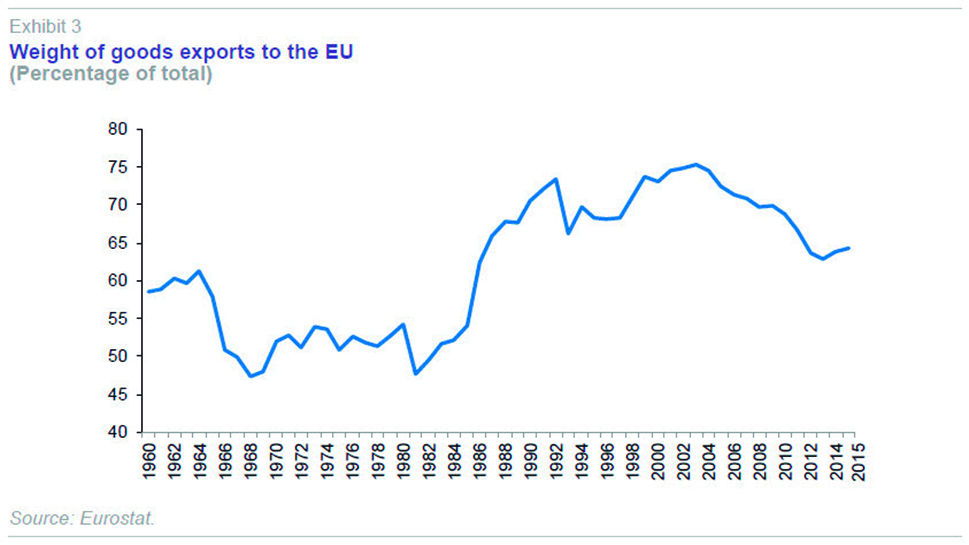

Indeed, the preceding decade –the 1980s– in which Spain joined what is now the European Union, was characterised by a sharp rise in exports to the region. Spain finally realised its dream of being a part of Europe, and its companies did so too, by making inroads into European markets, which must have implied a serious effort. Exhibit 3, which shows trade in goods only, shows the sharp rise in the proportion of exports aimed at the European community (intracommunity exports), which almost double as a share of the total. Spain’s companies took advantage of the European market’s opening up to their products, as they sought to offset the inevitable loss of domestic market share to companies from other European countries.

At the end of this decade of European integration, just over 70% of Spanish exports were destined for the European community. For many companies, particularly the larger ones, this was the culmination of their first stage of internationalisation, allowing them to leverage their comparative advantages, based in particular on lower labour costs, while undertaking a profound transformation of their products and production techniques.

However, as mentioned, it was in the 1990s that Spain’s exports enjoyed their biggest expansion, with rates of growth in volume terms of 10% a year, doubling those of the previous decade. This performance was not unique to Spain. Other countries on Europe’s periphery, such as Ireland and Greece, followed the same pattern, in sharp contrast to France, Germany and Italy, whose export growth was slower.

Over the course of this golden decade many companies with less than 200 employees started exporting, following the example of larger companies in the preceding decade. The data from SEPI’s Business Strategy Survey (Encuesta sobre Estrategias Empresariales, ESEE) show the percentage of firms with less than 200 employees that export to have almost doubled over the decade, with the increase in the number of small companies (with fewer than 100 employees) standing out in particular.

[3] Moreover, this change was most intense in those sectors that are currently the leading exporters, namely foodstuffs, textiles, chemicals, machinery, and transport equipment.

No less significant was the change that took place in the export intensity of the various types of companies,

i.e., the percentage of their output they sold on foreign markets. As a group, large companies,

i.e., those with over 200 employees, changed most. They started out with the same export intensity as small firms (around 20% of output), which is generally considered to be relatively low, with little transformative impact on companies’ manufacturing basis, and consequently, with limited capacity to prepare them for global competition. Over the 1990s, this share rose to 35%, with big increases in all the key exporting sectors, with the exception of food, drink and tobacco, which remain hampered by a low export intensity. This change led to large companies taking on a clear export orientation. In the case of firms with fewer than 200 workers, their export intensity also rose, although less vigorously, reaching the 25% threshold, which a recent study suggests is decisive.

[4] These achievements remained largely unchanged until the onset of the crisis.

Following the transformation that took place in the 1990s, the internationalisation of Spanish companies in terms of exports reached new heights, but remained basically reliant on EU markets. After the turn of the century, the following decade was characterised by the extension to new markets, with a significant decline in the share of European markets, and the introduction of new products and quality improvements. The decade was also characterised by a new and higher stage of internationalisation by large companies, with foreign investments to set up production abroad. This transformed Spanish companies into multinationals. This was a process that was mainly led by companies in the services industry, banking, telecommunications and power, but was followed by manufacturing companies in various sectors (metallurgy, non-metallic ores, chemicals, motor vehicles, and foodstuffs), thus boosting exports.

Thus, by degrees, Spanish exports, and more broadly, the internationalisation of Spanish companies, have become established, first spearheaded by a group of large companies, and then followed by other smaller ones. Spanish companies first made gradual inroads into markets to which they were geographically or culturally close, and then spread across the world. This is perhaps the most common path to internationalisation, taking place in a demanding context, and yielding good results.

It is also the path described by the Uppsala model, which posits that exporting is difficult, and that firms begin by increasing the share of exports in their business gradually, thereby gaining the experience they need to set up abroad as multinationals, and setting off a virtuous cycle in which exports and foreign investments reinforce one another.

Exports, economic recovery and the new growth model

A series of factors underpin Spain’s impressive export performance, including:

- A product mix increasingly attuned to the structure of global demand. Indeed, Spain’s specialisation in a mix of high, medium and low technologies has worked well. In high technology, exports include medical products, in medium technology, motor vehicles, chemicals and mechanical machinery, and in low technology, basic metals, and agrofoods products, in particular. Valuation of exports based on their levels of sophistication, in line with the work of Ricardo Hausman and Cesar Hidalgo, shows that half of exports belong to the group of medium-high to high sophistication exports (Alvarez and Vega, 2016).

- The high quality of the products offered, particularly in relation to their price, and a wide range of products with characteristics differentiating them from their rivals.

- A good combination of old and new markets. The geographical structure of Spain’s exports means that, despite the efforts made in recent years, they have a somewhat limited presence in Asia and North America, The focus on the EU has driven expansion until recently, and will do so again once Europe starts growing again, given the slowing of GDP growth in the emerging economies. Of course, that should not mean efforts to penetrate these markets should be stopped.

- A sizeable group of exporting companies with high comparative efficiency has already undertaken the most advanced stage of internationalisation, namely setting up subsidiaries in a large number of countries.

- The growing skill and capacity of Spanish firms to join global value chains has given greater stability to their foreign sales (Gandoy, 2014).

The value of Spain’s exports is currently 34% of GDP, a larger share than in France or Italy. Goods exports, which in Spain’s case are not as buoyant as services, have also surpassed France’s levels, and are close to those of Italy, at 24%.

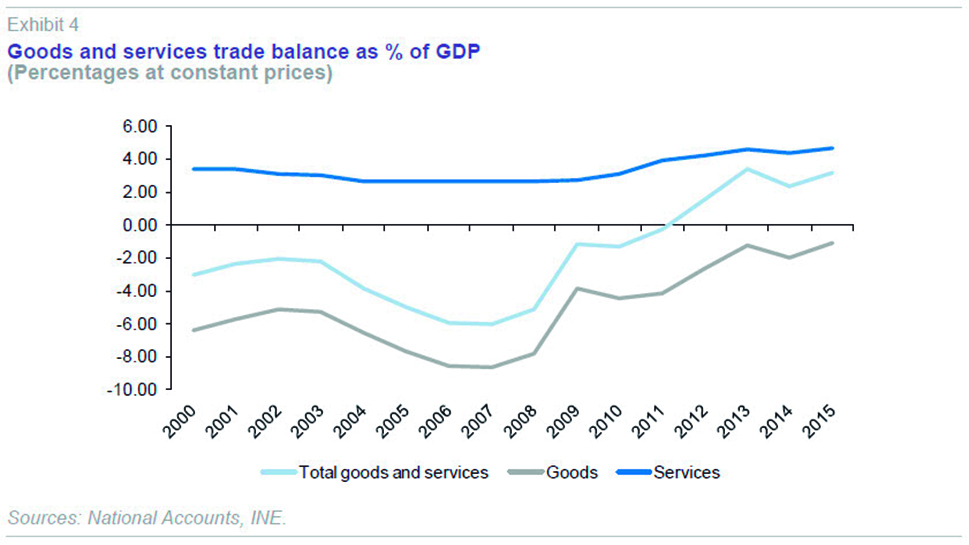

Nevertheless, these achievements are insufficient to guarantee the sustained high levels of growth the Spanish economy needs for significant job creation without creating imbalances. It should not be forgotten that Spain’s domestic demand growth tends to be accompanied by a strong increase in imports. Thus, the period of expansion preceding the recent crisis was characterised by a sharp deterioration in the goods and services trade balance (Exhibit 4). External demand therefore made a negative contribution to GDP growth, mainly reflected in the excessive and uncontrolled rate of domestic demand growth. This was compounded by the impact of other important factors, such as the strong rise in the euro against the dollar, which raised the price of Spanish products and lowered those of competitor countries.

[5]

A developed economy’s response to booming imports is to raise exports, and if it fails to do so, the inevitable result is excessive growth and domestic demand needs to be reined in. There is relatively little scope for substituting imports with domestic products and thereby reducing purchases from abroad. Developed economies specialise in certain ranges of products to achieve economies of scale and leverage their relative cost advantages (more in some ranges than others, depending on the price of their factors of production: labour and capital). It is difficult for production to meet demand for the entire range of products.

[6]

The recovery from the crisis and the future growth of the Spanish economy mean exports need to play a bigger role. Consequently, the upward trend in foreign sales should continue over the coming years, and there is sufficient competitive strength for it to do so. This does not alter the fact that solid support measures are needed, particularly today, with global trade stagnant. The current growth of domestic demand, at over 3%, tends to increase imports by almost 6% in normal conditions (although the average increase in 2014 and 2015 was 7%).

[7] This is a level exports could reach under normal circumstances, but is difficult at present unless global economic growth picks up.

Economic growth with more support for exports offers many additional advantages as well as keeping the external accounts more balanced. The first is fostering industrial development, with countless incentives for innovation and a better qualified workforce. This is precisely the big advantage associated with the reindustrialisation strategy announced by the European Commission, establishing the ambitious target of increasing industry’s share of total output from 16% to 20% of GDP by 2020. The second is to step up the rate of growth, efficiency and effort in innovation by exporting companies, whose progress is less sensitive to the domestic economic cycle. The third is a better understanding of emerging markets, encouraging and reducing the cost of the internationalisation of other companies, by offering strong support to public export promotion policy.

Concluding remarks

This article has described how Spanish exports have risen during the economic crisis, showing Spain’s performance to have excelled in comparison to that of other European countries. The strength shown by this rise is partly due to the crisis, which represents an incentive to look for foreign markets, but above all it rests on a trajectory of decades of rapid expansion, which was given a strong boost by Spain’s joining the European Economic Community in 1986, and achieved its greatest successes in the 1990s. This successful track record was the result of a profound transformation of the Spanish economy’s productive structure and the technological and organisational basis of its constituent companies, which were obliged to respond to the challenge of the Spanish market’s greater exposure to international competition resulting from globalisation and membership in the European Economic Community. Spanish companies have now reached high levels of internationalisation, not only through exports, but also foreign investment, reflecting their highly competitive products, which are increasingly attuned to global demand, and offer quality and differentiation.

In any event, more stable and sustained economic growth requires Spanish production to remain focused on foreign markets, and increasing companies’ export intensities, as the recovery in domestic demand stimulates imports and so raises the risk of imbalances recurring in goods and services trade.

Making growth more export based offers a number of advantages, such as increasing companies’ efficiency and productivity, as well as sustaining rapid rates of growth. It is therefore one of the main changes required to Spain´s productive model.

Notes

This article summarises part of Myro (2015).

In the period mentioned, Spanish exports grew faster than France’s or Italy’s, and at the same rate as Britain’s.

In the following decade, the 2000s, the number of exporting companies grew much more slowly, except in the case of firms with between 20 and 50 employees, which had been left behind in the previous decade. However, once again there has been considerable progress in the number of exporting companies during the crisis, which has obliged them to look for foreign markets.

Past this threshold, companies seem to obtain greater productivity gains and start behaving like multinationals, setting themselves apart from non-exporting companies (or companies who export less) (Merino de Lucas, 2012).

Another factor was the rise in unit labour costs, although this probably had a much smaller effect than the increasing value of the euro, which firms consider to be exogenous and harder to predict.

This can be illustrated with an example. If demand for motor vehicles grows, this increases sales of top-of-the range models as well as mid-range and cheaper vehicles. However, if Spain’s advantages are based more on lower salaries than higher technology, domestic production will tend to specialise in the lower end of the market (in practice, Spain’s car manufacturers are largely foreign owned). Spain’s response should therefore be to increase exports of the models it manufactures, rather than try to produce more sophisticated cars, which would take longer to achieve as it would mean first raising the technological level of the companies operating in Spain. This does not mean that Spain’s output is not competitive, quite the contrary, to the extent that it is ever more closely integrated in the grand European assembly line, as recent studies show (Córcoles, Díaz Mora and Gandoy, 2012).

Income elasticity of exports is near 2.

References

ÁLVAREZ LÓPEZ, E., and J. VEGA (2016), “La sofisticación de las exportaciones españolas,”

Blog de Economía Aldea Global, April.

CÓRCOLES, D.; DÍAZ MORA, C., and R. GANDOY (2012), “La participación en redes internacionales de producción: un factor de estabilidad para las exportaciones españolas,”

Economistas, nº 130: 83-95.

EEPINGER, P. S.; MEITHALER, N.; SINDLINGER, M., and M. SMOLKA (2015), “The Great Trade Collapse and the Spanish Export Miracle: Firm-level Evidence from the Crisis,”

Economics Working Papers, 2015-10, Aarhus University.

GANDOY, R. (2014), ”La implicación española en cadenas globales de producción,” in ALONSO, J. A., and R. MYRO (eds.),

Ensayos sobre economía Española, Thomson-Reuters.

GROS, D. (2016),

“Is this the end of globalization?,” World Economic Forum,

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/03/is-this-the-end-of-globalizationJÄÄSKELÄ, J., and T. MATHEWS (2015), “Explaining the slowdown in global trade,”

Bulletin of the Reserve Bank of Australia, third quarter: 39-46.

MERINO DE LUCAS, F. (2012), “Firms’ internationalization and productivity growth,”

Research in Economics, vol. 66, nº 4: 349-354.

MYRO, R. (2015),

España en la economía global. Claves del éxito de las exportaciones españolas. November 2015.

Rafael Myro. Madrid Complutense University