Another twist to European bank restructuring

The global financial sector faces serious challenges to boost profitability. Restructuring is part of the necessary solution to these challenges, but the extent to which economies of scale will be accompanied by economies of scope is yet to be determined, as a successful combination of traditional and new digital technologies is yet to emerge.

Abstract: 2016 has been a somewhat difficult year for the European banking sector, with big swings experienced on stock markets. The global financial situation and unprecedented market conditions, with real negative interest rates, are major factors in the current difficulties. The banking industry worldwide – and the European industry is no exception – is facing a shift in model driven by changing technology, an excessive delay in responding to the need to cut overcapacity, and a grim legacy of losses from the crisis and serious downward pressure on returns. The response has included widespread branch closures and staff cuts, with Spain having the advantage of having begun an orderly process of change some years ago. Estimates show there are significant potential cost savings to be made from increasing the average size of financial institutions, but doubts remain as regards economies of scope as it is not yet clear which technologies and services will provide the most advantages.

International context: Negative rates and the search for returns

Stock market valuations initially recovered from the substantial losses in the early months of the year, but have since become mired in volatility and uncertainty. The sources of risk have not significantly worsened. The main factors are still instability in emerging economies, geostrategic shifts in energy markets, and negative real interest rates. However, in an unprecedented international financial scenario, marked by the volume of accumulated debt, the flood of “official” liquidity, and low returns on assets, the long-term path of the global economy remains unclear.

The banking sector has been one of the most powerfully affected by this volatility, particularly in Europe, where doubts persist about recovery, the effectiveness of monetary policy, and the capacity for fiscal coordination.

At its April meeting, the Executive Board of the European Central Bank indicated that its expansionary monetary policy may have to become more expansionary still. In particular, the statement highlighted that: “Regarding non-standard monetary policy measures, as decided on March 10th, 2016, we have started to expand our monthly purchases under the asset purchase programme to 80 billion euros, from the previous amount of 60 billion euros. As stated before, these purchases are intended to run until the end of March 2017, or beyond, if necessary, and in any case until the Governing Council sees a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation consistent with its inflation aim. Moreover, in June, we will conduct the first operation of our new series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO II) and we will commence purchases under our corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP).”

Therefore, even though the ECB considered that: “The pass-through of the monetary policy stimulus to firms and households, notably through the banking system, is strengthening,” it kept open the option of using new instruments, with significant new features in corporate bond purchases. The statement also said that “uncertainties persist and relate, in particular, to developments in the global economy.” The tone of the International Monetary Fund’s April Global Financial Stability Report was similar, making several allusions to risks affecting the banking sector. In particular, the report mentioned that “European bank equity prices declined along with global bank equities, pushing valuations to a record discount for U.S. banks. The hardest hit banking systems within the euro area in February have been those of Greece, Italy, and to a lesser extent, Portugal, along with some large German banks.” The IMF considers the banks’ problems to be “structural” with “problems of excess bank capacity, high levels of NPLs, and poorly adapted business models.”

From a more technical perspective, the IMF report distinguishes three specific current and potential areas of concern for European banks:

- Troubled assets: Weak profitability increases the difficulty of dealing with NPLs by reducing banks’ capacity to build capital buffers through retained earnings. For some banking systems, this comprises a structural weakness. Euro area banks still have around a trillion euros in NPLs. Greece and Italy are considered particularly problematic.

- Business model challenges: The transition to new business models may prove expensive for some banks. Reducing their exposure to particular sectors, banks not only have to absorb the legacy of losses from previous investments, but meet significant legal costs. Market turbulence is making things more difficult as it allows few options for profit generation.

- Regulatory challenges: Banks face clear demands for more capital to build up their buffers as well as comply with regulatory requirements. This is not just a question of increasing capital and reserves, or preparing for the leverage and liquidity requirements accompanying Basel III up to 2019. It is also necessary to consider assets that can potentially be used to respond to losses (bail-in) rather than tax payers’ money (bail-out). This includes new total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) requirements and minimum requirements for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL). These provisions comprise a regulatory framework that, while clearly necessary, makes European banks’ management and regulatory compliance significantly more difficulty, particularly given the convergence of legal pressures from different sources.

As the IMF suggests, these regulatory challenges have been reflected in bank asset valuations, above all in situations of stress. It explicitly mentions the “bail-in of the subordinated debt of four small Italian banks late last year” and the concern over the “treatment of select senior debt holders of Novo Banco (Portugal),” which “has led to a perception of uneven handedness and increased uncertainty that has dented confidence.”

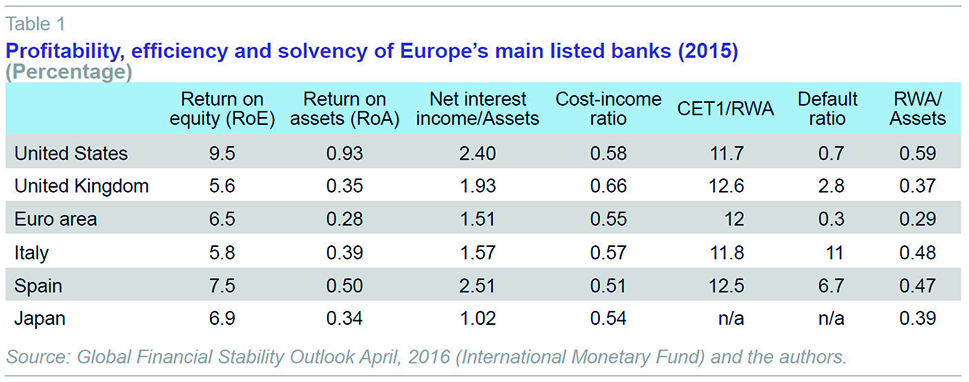

In any event, the solvency of the European banking sector has improved significantly since the financial crisis. And the state of the Spanish banking sector in this context also looks favourable. As Table 1 shows, the return on equity (RoE) of Spain’s largest listed banks was 7.5% in 2015. This is better than the Eurozone average (6.5%) and their return on assets (0.5% compared with 0.28%) was also better. Even with significant downward pressure, the interest margin in Spain (2.51%) remains the highest in Europe.

Spanish banks rank favourably on the cost-income ratio, which is a measure of efficiency (0.51% compared to a eurozone average of 0.55%). As regards solvency, the core-equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio was 12.5%, compared with a eurozone average of 12%.

One aspect that is always controversial is the consideration of the level of balance sheet risk, approximated by risk-weighted assets (RWA). The “RWA/total assets” ratio for Spanish banks was 0.47, compared to a Eurozone average of 0.29. This discussion can also be seen as part of the ongoing debate on how public debt is to be treated on the balance sheet. Data from the European Central Bank show Italian banks to have a public debt exposure of 10.5% of their balance sheet. The figure for Spain is 8.8%. Even when setting a limit on it seems plausible, it is worth asking to what extent it makes sense to penalise these holdings rather than address the root problem of sovereign risk (fiscal sustainability). This is all the more relevant given that the ECB is buying large quantities of these assets under its monetary expansion strategy.

At the more detailed level, as regards the health of the European banking sector and the persisting doubts, two recent cases have caused particular concern: The controversy over Deutsche Bank’s exposure to structured products, and the general state of the Italian banking sector, with the creation of an asset management company or “bad bank”.

A long time has passed since the German bank Hypo Real Estate was bailed out in 2008, but doubts still persist as to German banks’ exposure to structured products. This no longer concerns subprime mortgages, so much as complex derivatives in general. Germany’s financial institutions have not been the most willing participants in the enhanced transparency exercises (or the various Europe-wide stress tests performed). More recent efforts have calmed some fears, but are still a long way from removing uncertainty. The underlying problem is the loss-absorption capacity referred to earlier. Deutsche Bank is, in fact, the first major European bank that has had to confront its contingent convertible bond (CoCo) holders with substantial losses.

What is known, although the details are unclear, is that Deutsche Bank holds derivatives valued at 50 trillion euros, 17 times Germany’s GDP. The “real” net risk (cancelling or offsetting all these risks) is calculated to represent an exposure of up to 500 billion euros. But the biggest problem would be the contagion effects unwinding these derivatives would have on third parties, as this is an intrinsic feature of derivatives. This has been known since 2008.

In Italy’s case, the banking market is weighed down by NPLs, which, far from being under control, are still rising alarmingly. The volume of NPLs rose to 360 billion euros in early 2016, and the big concern is that the trend is still upward, while Italian banks’ profitability and loss absorption capacity continues to shrink. In January, the Italian government reached an agreement with the European Commission to set up an asset management company for these impaired assets. This was finally approved on April 20th. This fund has been called “Atlante” and all Italy’s banks have a share of its capital, with contributions totalling four billion euros on the most recent estimates. The fund has an innovative structure for a “bad bank”. Atlante does not aim to manage these impaired assets directly, but rather “unblock the market” so that Italy’s banks can do so. Atlante will invest in shares in Italian financial institutions which, in turn, will increase their stockmarket capital for this purpose. At the same time, the government will underwrite some of Atlante’s shares, guaranteeing at least the fund participants’ senior tranches. Atlante could also support banks’ individual restructuring plans. The European Central Bank (ECB) has highlighted the risks of this approach, warning that without a capital increase, banks would struggle to tap sources of credit to improve their solvency levels. The advantage and disadvantage of this management model is that it puts everything in the industry’s hands, without intervention or a clear segregation of assets. The viability of this mechanism if the deterioration continues and profits fail to rise is by no means certain.

Recent efforts and the outlook for bank restructuring in Europe

In recent weeks, there has often been news in Europe’s financial press of European banks announcing restructuring plans. Basically, this restructuring involves branch closures and staff cuts. In the case of Spanish banking institutions, this is a less traumatic continuation of a process of orderly change that began during the crisis. In other European countries, however, the fact that serious restructuring was not undertaken earlier is forcing many entities to adopt more drastic solutions over shorter timeframes.

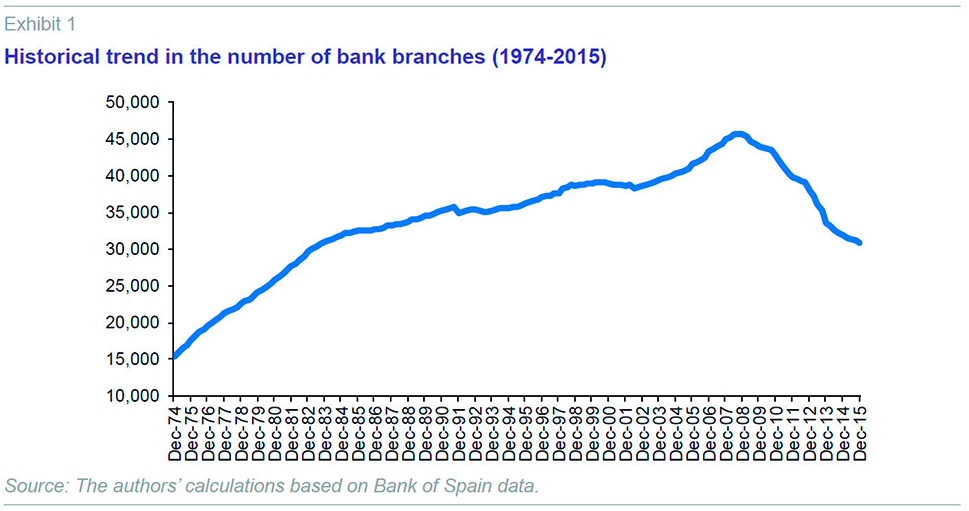

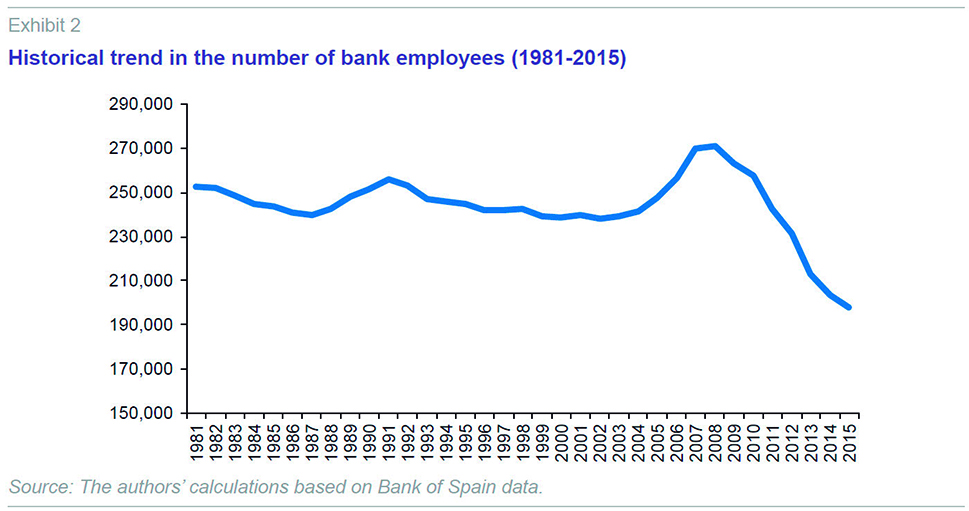

In the January 2016 issue of Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, we reviewed the recent progress and outlook of Spain’s bank restructuring process. In particular, we highlighted that the number of employees had dropped from 231,389 in 2012 to an estimated 194,688 at the end of 2015. The number of branches was cut, from 37,903 in 2012 to 31,021 in 2015. And by 2019 the number of branches could be around 28,000 and the number of employees 180,000.

A look back at the past may help put the scale of these transformations into perspective. Between 1974 and 2000, Spanish banks increased their number of branches by a factor of 2.5 (Exhibit 1). Between 2003 and 2008, before the first signs of the financial crisis in Spain, 6,898 new branches were opened, more than in the preceding 18 years. At the end of 2015, the number of branches was back to 1980s levels.

Something similar may be concluded in the case of bank employees, although here the adjustment has been more moderate. Financial institutions kept their workforce fairly stable over the 1990s and in the early 2000s. During the credit boom, lasting from 2003 to 2008, Spain’s banks took on 31,752 new staff. However, between 2009 and 2015, they shed 73,025 employees.

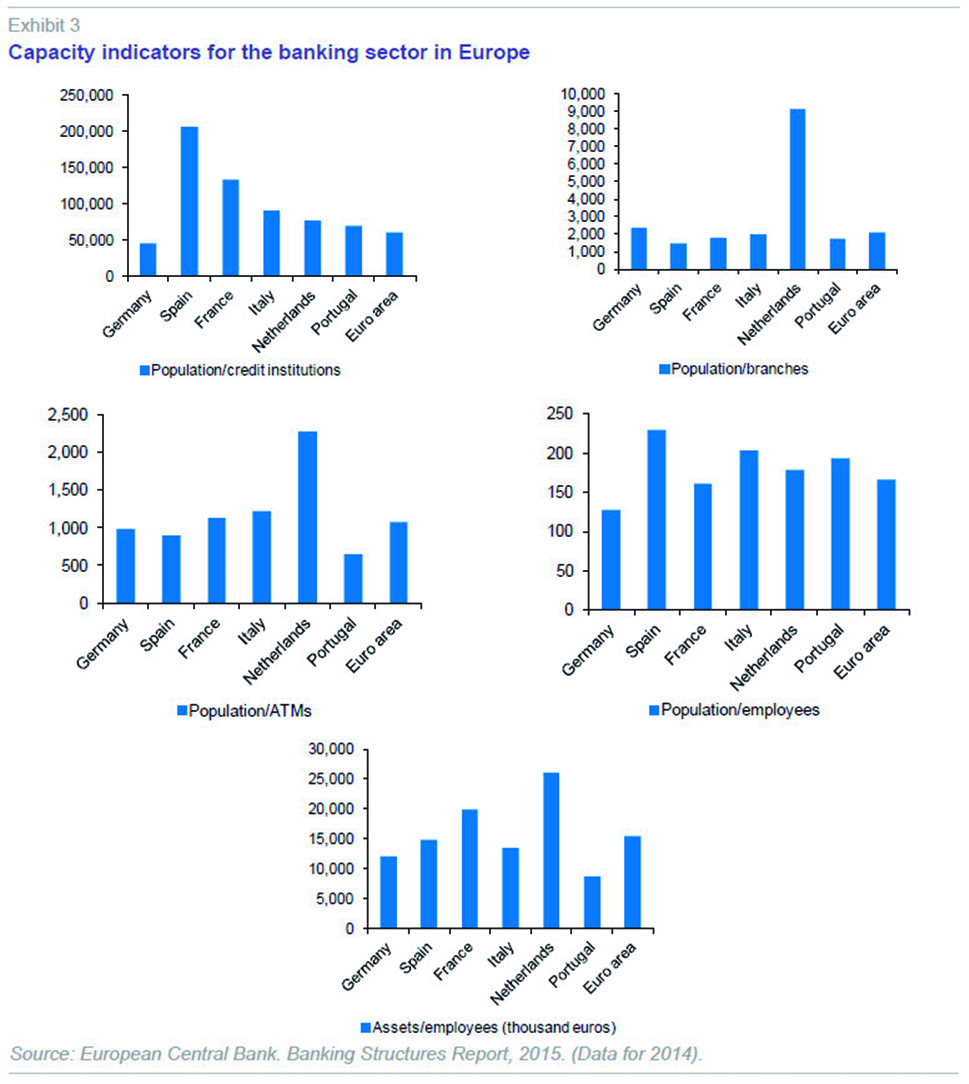

Although the adjustment was – and remains – necessary throughout Europe, it is worth mentioning some of the peculiarities of Spain’s banking infrastructure in terms of the capacity indicators (Exhibit 3) published by the ECB in its 2015 Banking Structures Report (the most recent data available are for 2014, but remain valid for comparative purposes).

In Spain, there is a banking institution for every 205,593 inhabitants, compared with a Eurozone average of one per 60,046 inhabitants. However, the large number of branches explains why customer service is close and personalised, with 1,452 inhabitants per branch compared to a Eurozone average of 2,111. The position is similar as regards ATMs, with one per 892 inhabitants compared to one per 1,078 in the Eurozone. The Spanish banking industry’s strategic choice has been to have more smaller branches with fewer employees than is typical in Europe. This translates into one bank employee per 230 inhabitants in Spain compared to 166 in Europe. However, it is worth noting that the relative productivity of this model, given that each bank employee in Spain manages an average of 14.7 million euros, is entirely in line with the 15.4 million euros average for the Eurozone, although it is higher than the 12.1 million euros average in Germany or 13.5 million euros in Italy.

Mergers: Economies of scale are back. Economies of scope will be next

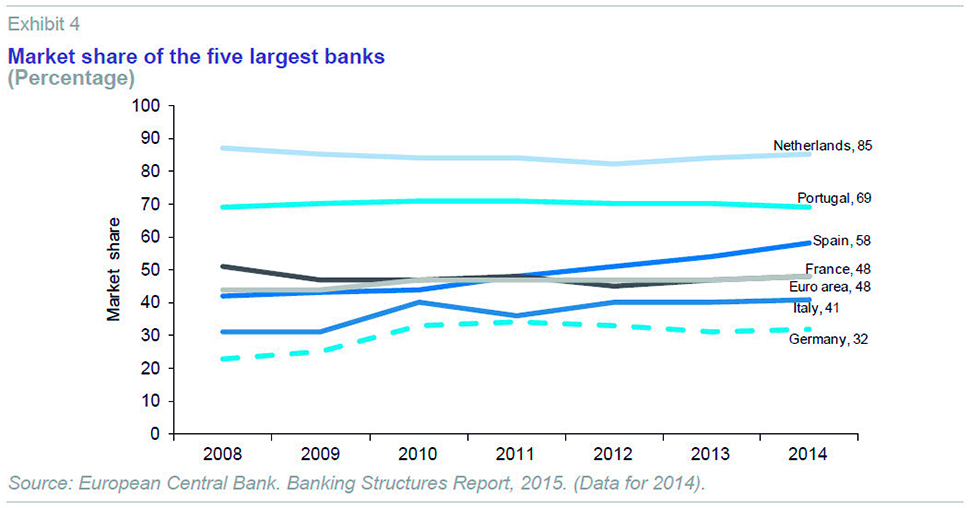

Changes in bank structure are related to changes in concentration in the sector. Mergers and acquisitions tend to increase significantly in the wake of a financial crisis. The persistence of overcapacity in many countries is being exacerbated by a profitability crisis in a context of negative real interest rates. It comes as no surprise that, as Exhibit 4 shows, the market share held by the five biggest banks in Europe’s main financial systems has increased. In the Netherlands this share is 85%, in Portugal 69%, in Spain 58%, and the Eurozone average is 48%.

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to associate the level of concentration with the intensity of competition. There are countries in which almost all of the banking business is shared between less than five institutions – such as Canada – but the competition between them is nevertheless intense. And there are others, such as the United States, where there are thousands of institutions, but the strength of competition depends on the ability of different operators to set prices in local markets. A growing number of studies suggest that in markets such as Spain’s, competition is determined by rivalry and not the number of competitors or market concentration (Carbó, Rodríguez and Udell, 2009). What is more, the importance of market concentration is set to decline yet further as the banking business gears itself more towards digital technologies rather than physical branches.

It could be argued that the mergers and acquisitions that are affecting and will continue to affect the Spanish and European banking sectors are explained by overcapacity and the technological change implied by digitisation. Although both these factors are important, this explanation would be incomplete. Financial consolidation is also playing a role in the changing interaction between entities and financial markets and in the recovery of economies of scale (cost savings as institutions become larger), which had been considered largely exhausted since the 1990s.

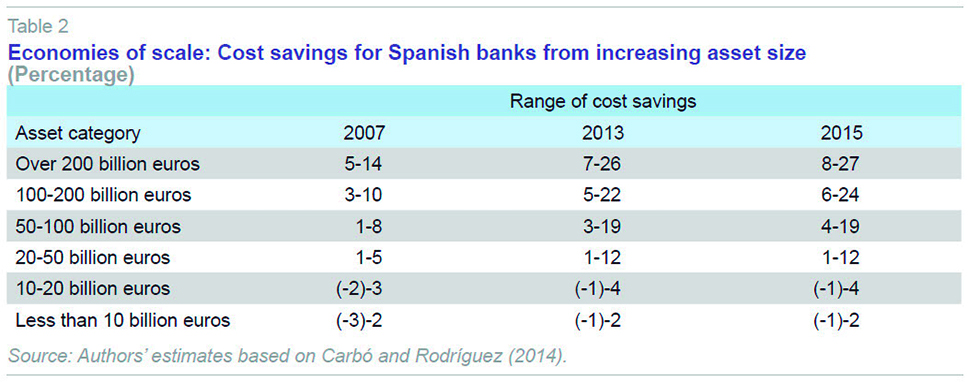

Carbó and Rodríguez (2014) propose a methodology explaining how to calculate economies of scale in a complex banking business environment such as the present. Without going too far into the technical details, this methodology considers the advantages of diversification of risk while the size of the business increases. It also considers the ratio of external debt to own funds. This is important because, if it is not taken into account, it would imply that two banks with identical assets would be considered equally efficient even if one had more debt relative to its capital. Using Carbó and Rodríguez’s methodology to determine the Spanish banking sector’s growth potential and resulting cost savings shows these savings to have risen significantly between 2007 and 2014. In particular, Table 2 shows how much costs could be reduced for various different categories of assets in the Spanish banking system.

The findings suggest important cost savings of between 8% and 27% for entities with assets of over 200 billion euros. The range probably affecting most possibilities of financial integration in Spain is that comprising institutions of between 50 billion and 100 billion euros, where the savings from reaching this scale lie in the 4% to 20% range.

The overall conclusion from these estimates is that Spain’s banks can benefit from integration processes by achieving cost savings from greater scale. However, the challenge remains that of exploiting economies of scope, which arise out of synergies when combining traditional products with new ones. Incorporating fintech alternatives into the banking mix is clearly one option for achieving these kinds of economies of scope. However, it is not yet clear which technologies and services will provide these advantages.

References

CARBÓ, S., and F. RODRÍGUEZ (2014), “El sector bancario español ante un nuevo paradigma: Reconsideración del valor del tamaño,” Papeles de Economía Española, special issue “Nuevos negocios bancarios”, 19-30.

CARBÓ, S.; RODRÍGUEZ, F., and G. UDELL (2009), Bank market power and SME financing constraints, Review of Finance, vol. 13: 309-340.

Santiago Carbó Valverde. Bangor Business School and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas